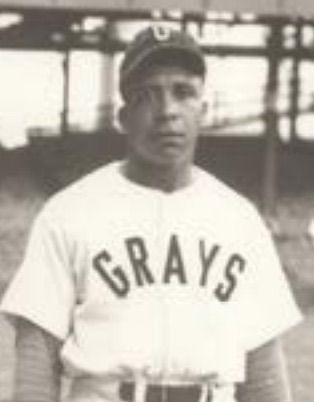

Eudie Napier

Euthumn Napier remembered a bus ride north on April 15, 1947, on which he joined his Homestead Grays teammates in whiling away the hours by talking about the biggest baseball news of the day. Jackie Robinson had started at first base that day for the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking the modern color barrier.

Euthumn Napier remembered a bus ride north on April 15, 1947, on which he joined his Homestead Grays teammates in whiling away the hours by talking about the biggest baseball news of the day. Jackie Robinson had started at first base that day for the Brooklyn Dodgers, breaking the modern color barrier.

“We were all thrilled for him,” Napier recalled many years later. “We never thought it would happen. It was all we talked about on the bus. To say the least, it was a thrill.”1

Though it was not yet obvious, Robinson’s debut also marked the beginning of the end for the Negro Leagues. Napier, who was 34 at the time, would be too old to have a serious shot at a spot in the majors. He was finally on the cusp of his own starring role with the Grays after serving as a backup to Josh Gibson, who had died just three months before Robinson’s first game. Napier, a 5-foot-9, 190-pounder, performed well for the Grays, being named to postseason all-star teams in 1947 and ’48. Known as a defensive catcher, Napier backstopped the Pittsburgh Crawfords and the Grays before spending two seasons of Organized Baseball with the Farnham Pirates in the Canadian province of Quebec. He wound up his career playing sandlot baseball in Pittsburgh in his 40s.

In looking back at his career in 1978, Napier expressed resignation at having had to play segregated baseball through the seasons in which he would have been at his physical prime. “I’m not bitter,” he said. “I had a lot of fun. You knew they weren’t going to let the black man into baseball, so you never gave it a thought. Actually, playing baseball back then, I was making more money than the majority of black people, so I couldn’t complain.”2

His reminiscences of life on the road included anecdotes about how baseball players were not immune from the insults and degradations of Jim Crow rules. Most hotels were forbidden and fountains were reserved for whites. Many restaurants served blacks only from the rear entrance. Once, while he was traveling with the Grays, the team stopped at a gas station in Mississippi to replenish a water supply. They spotted a water fountain next to a cola machine. “We asked the man in charge if we could go over and get some water,” Napier recalled. “The man told us he didn’t have any water.”3 Another time, a storekeeper in Georgia smashed pop bottles used by the players rather than have them washed and reused by whites.

After Napier’s death, his namesake son recounted his father’s favorite story about playing in the South. “They were barnstorming and playing an all-white team in Georgia,” Euthumn Napier Jr. told the Pittsburgh Press in 1983, “and the park didn’t have a loudspeaker. The umpire would come up and announce the lineups. He announced the home team like: ‘Mr. Smith pitching. Mr. Jones catching.’

“My dad’s team had a little pitcher, a guy they called Groundhog. When the guy announced my dad’s team, he yelled out, ‘Little nigger pitching. Big nigger catching.’ My dad, he really laughed about that. See, that would have really made me mad. But he laughed about it. And they went on to kill the team by some outrageous score.”4

The catcher was known as Eudie or Eddie or Nap or Nape throughout his career, as his uncommon given name proved difficult to master. Authors and sportswriters rendered it incorrectly as Ethan, Ethum, Eutham, Eudis, and Euthumm over the years.

Euthumn Napier was born on a 400-acre farm near the county seat of Milledgeville in Baldwin County, Georgia, on January 3, 1913. He was the youngest of eight boys and one of 12 children to live beyond infancy born to Grace and Horace Napier. The boy was named for a kindly shoemaker who lived nearby. “They’d run out of names,” his eldest son quipped in a 2017 interview.5 The family moved north to Pittsburgh soon after Napier began elementary school, his father giving up farming for laboring work.

Napier made the varsity gridiron team at Allegheny High School and played in three games, which gained him a brief mention in the local African-American daily newspaper. “Allegheny also has two other colored boys on the football team who look to be very promising. They are Euthumn Napier and James Robinson,” the Pittsburgh Courier reported in 1931. “These boys have done some fine playing, and deserve to be praised and encouraged.”6 The next month, both young men also earned a spot on the roster of the school’s basketball team.

After his father died in 1929, not long after the stock-market crash, Napier combined studies with work, as he needed to help support his mother and younger sisters.7 As a young man, he performed with the Rialto Singers Quartet, part of a theatrical troupe formed as part of a Works Progress Administration (WPA) job-creation program during the Depression. The troupe disbanded in 1936, their final performance conducted for free for unemployed workers and their families at the Labor Temple in Pittsburgh. Napier would later be known as among the better voices on the Pittsburgh Crawfords, as the players sang spirituals and barber-shop songs to pass the time on the long drives between games.

Napier caught, pitched, and sometimes managed the Monarchs team in the second division of the Greater Pittsburgh League, a sandlot circuit. By the start of the 1939 season, he had shown enough skill to be identified as an understudy to Josh Gibson by Cum Posey, owner of the Homestead Grays.

On November 23, 1940, Napier married Leola Beatrice Compton, who was working as a folder at a laundry. They had met in high school, where the young New Orleans-born woman was described in her graduating yearbook as “a pleasant girl with high ambitions.”

By the summer of 1944, Napier was sharing catching duties with Jeff Gwynn on a tour by the Pittsburgh Crawfords as they faced the Chicago Brown Bombers in a barnstorming series.

Napier’s speed and power impressed a reporter with the Winnipeg Free Press when the Crawfords returned to the Manitoba capital in 1945 to face the Honus Wagner All-Stars. In one game, Napier was robbed of a home run when a blow to right field failed to clear the park only because it hit a broadcast booth atop the adjacent hockey rink whose exterior wall also served as the ballpark’s fence. Napier was held to a double. Behind the plate, he always raced up the line after a ball was struck to an infielder, reaching “first base to cover up just about as soon as the hitter.”8

The Grays added Napier to the roster for the 1946 season, though he saw limited service as a backup. Even after the death of the great Josh Gibson at age 35 in January 1947, Napier competed for the starter’s role against the likes of Robert Gaston, Gibson’s longtime backup, and Victor Sosa, a Cuban import.

With integration coming to provincial baseball, Napier joined a northward migration of some Negro League players to Canada. In 1949, he signed with the Farnham Pirates, a team in the independent Provincial League. The French-language newspaper La Patrie scouted him for its readers: “Il est un frappeur de longue distance” (He’s a long-distance hitter.).9 The circuit had six teams in Quebec’s Eastern Townships region, serving as a great summer entertainment for a French-speaking area with a sizable English-speaking minority. Napier made the all-star game, though he was the goat when the winning run was scored on a passed ball. He was with the club in 1951 when the Provincial League served as a Class-C circuit as he made his debut in Organized Baseball at age 38. Among his teammates was Josh Gibson Jr., the son of the late immortal.

The left-handed-batting Napier hit .285 with 8 home runs in 319 at-bats with Farnham in 1951. He had seen only spot duty with the Grays over several seasons with only 103 plate appearances recorded in parts of four seasons, according to statistics compiled by Baseball-Reference.com. His composite average was .259.

Napier also spent part of the summers in the semiprofessional Major Inter-County League in the neighboring province of Ontario, playing briefly for the Brantford Red Sox and the Guelph Maple Leafs. In winters, he played ball in Puerto Rico (Santurce Cangrejeros), Panama (Chesterfield Smokers), and Venezuela (Cerveza Caracas). By 1954, he was back in the Greater Pittsburgh League, smacking homers for the Bellevue team.

After his playing days ended, Napier found out that his career in the Negro Leagues had brought neither a pension nor an offer for coaching jobs. He worked two janitorial jobs, starting on the overnight shift at the Pittsburgh Press from 10 P.M. until 6 A.M. before moving on to sweeping floors at the Joseph Horne’s department store from 7 A.M. until 3 P.M. He retired around the date of his 67th birthday in 1980.

Over the years, he stayed in contact with some of his old teammates, including Sam Bankhead, who died in 1976, as well as Willie Pope and Wilmer “Red” Fields.

Napier died of cirrhosis at Suburban General Hospital in the Pittsburgh suburb of Bellevue on March 16, 1983, at the age of 70. He was survived by his wife and by their two adult sons, Euthumn Jr. and Michael. Napier is buried in Union Dale Cemetery in Pittsburgh.

For decades, his woolen Homestead Grays uniform was kept in a cedar chest. More than 20 years after his death, the rare artifact was placed on display at the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh, which includes the Western Pennsylvania Sports Museum.

Napier was inducted into the Pennsylvania Sports Hall of Fame, Western Chapter, in 1978. In an appropriate coda for his career, his first name is misspelled as “Eutham” on the plaque.

This biography appears in “Bittersweet Goodbye: The Black Barons, the Grays, and the 1948 Negro League World Series” (SABR, 2017), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Lester, Larry and Sammy J. Miller. Black Baseball in Pittsburgh (Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2001).

Ruck, Rob. Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987).

Swanton, Barry, and Jay-Dell Mah. Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2009).

Interviews with Michael Napier and Euthumn Napier Jr., September 14, 2016.

Notes

1 Steve Hecht, “Euthumn Napier Remembers When Only the Ball Was White,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 20, 1978: 44.

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 Tom Wheatley, “A Part of Local Lore Died With Napier,” Pittsburgh Press, March 30, 1983: 86.

5 Telephone interview with Euthumn Napier Jr., September 14, 2016.

6 Theresa Cutts and Theodore Maddox. “Allegheny High School,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 5, 1931: 16.

7 In 1978, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette noted offhandedly that Napier played for the Grays under an assumed name while still in high school. If so, the alias was not revealed, and neither of his sons can confirm that this was the case. See “Napier on baseball,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, April 20, 1978: 44.

8 “All-Stars Defeat Crawfords, 7 to 4,” Winnipeg Free Press, September 5, 1945: 13.

9 “Max Lanier a signé pour les Cubs et Smolko pour Granby dans la ligue Provinciale,” La Patrie (Montreal), April 8, 1949.

Full Name

Euthumn Napier

Born

January 3, 1913 at Milledgeville, GA (US)

Died

March 16, 1983 at Bellevue, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.