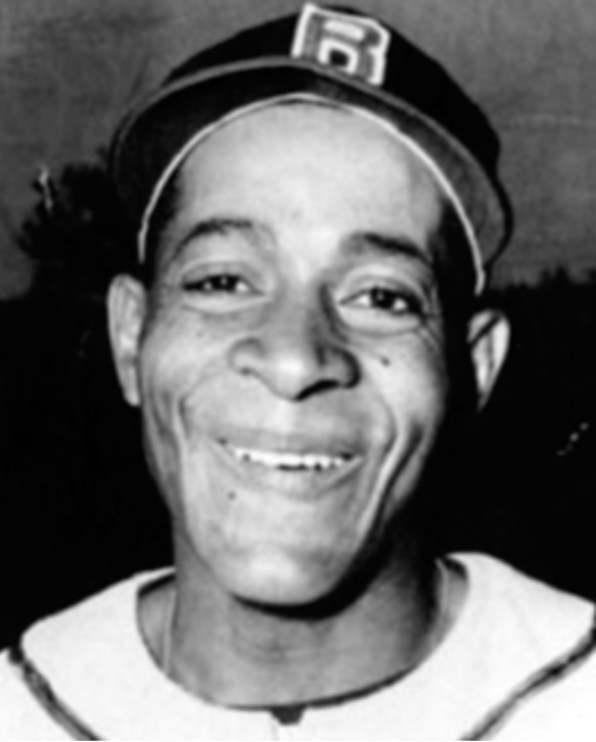

Jimmy Wilkes

“They used to say Brantford could put its left-fielder five feet from the foul line, the right-fielder five feet from the other line and  Jimmy Wilkes would cover the rest.” — Bob McKillop1

Jimmy Wilkes would cover the rest.” — Bob McKillop1

“Riding the bus again!” Jimmy Wilkes said, his voice cracking with excitement. “I love it. Now, that brings back memories.”2 The 69-year-old Wilkes was on his way to Cooperstown, New York, to the Baseball Hall of Fame with about 20 other Negro League veterans. They had stayed in a hotel in Albany the night before and were on their way to honor their former teammate Leon Day, who was being inducted posthumously.

They reminisced about the days when they barnstormed the country, including the Jim Crow South, where they could not sleep in its hotels, use its bathrooms, or eat in its restaurants. They were segregated because of the color of their skin and could not play in the same game as white players until Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier. We will never know how great some of them were, and many stories have been silenced with the passage of time. “Their statistics were often lost, their glory obscured,” wrote Sean Peter Kirst.3 But on that July day in 1995, these former players were among baseball’s honored guests who would exit the bus from another era, making sure we would always remember their stories. Jimmy Wilkes’ life and career provide one such tale.

There was the game when Wilkes made a catch at the deepest part of Yankee Stadium. “Josh Gibson was batting, for the Homestead Grays,” Wilkes recalled. “He hit a line drive to deep center field. That was in the old Yankee Stadium, where it went a long ways back. I turned my back and started running. I reached up and stuck my mitt out and there was the ball. I was way back there. I turned around and there were the monuments for Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig. It’s been called one of the greatest catches ever in Yankee Stadium.”4 Perhaps the only difference between the legendary great catch Willie Mays made in the 1954 World Series and this catch by Wilkes is that Wilkes’ games were not televised or followed by hordes of reporters, and its image has passed with those who saw it.

“If me and Willie were in the same outfield,” Wilkes said, “they wouldn’t need anybody else out there. We’d have caught everything that came out there.”5

Wilkes was nicknamed Seabiscuit after the legendary racehorse and was the speedy leadoff hitter for the Newark Eagles. He was known for his electric speed in the outfield for nearly 20 years. He played in Canada for 10 years, where he remained for the rest of his life and umpired for another 26 years. Brantford, Ontario, became his adopted hometown, and “people who were too young to have seen him play, or who weren’t even born then, looked up to this fun-loving guy whose ear-to-ear smile seemed to be permanent and whose laughter was infectious.”6

James Eugene “Jimmy” Wilkes was born on October 1, 1925, in Philadelphia to Histron and Minnie (Gullick) Wilkes. The 1940 census lists the family living at 8509 Mornan Avenue in Philadelphia. Histron was a “laborer” for the “evening newspaper,” but reported no income or weeks worked for 1939; however, there is a “yes” written in the box for “income from other sources.” Mary Washington, listed as a widowed sister-in-law, also lived with them and worked as a housekeeper for a private family, earning $314 for the year. The family owned their home, which was valued at $2,000.

Wilkes graduated from John Bartram High School in Philadelphia, where he played on the baseball team. The Clippers won the Public High School Baseball Championship of 1943 and Wilkes went 3-for-3 with four RBIs in the championship game, two of them coming on a triple (the only extra-base hit of the game), which proved to be the deciding runs in the 5-3 win.7

After high school Wilkes served a brief stint in the US Navy during World War II but was discharged because of an injured back.8 On July 25, 1944, Wilkes married Hattie M. Davis. The couple would have four children: James, Janice, Patricia, and Eugene.

Wilkes played in 1945 for the Brooklyn Brown Dodgers of the short-lived United States League. The USL, a third major Negro league that began play that year, was the brainchild of former Pittsburgh Crawfords owner Gus Greenlee. In order to lend credence to the endeavor, Greenlee struck a deal with Brooklyn Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey, who prompted the move of the USL’s Hilldale franchise to Brooklyn. Oscar Charleston, Wilkes’ manager and a scout with the Dodgers organization, brought Wilkes to the attention of Effa Manley, the owner of the Newark Eagles. She was impressed with Wilkes’ speed and defense, and he remained on the team to finish the season and batted over .300.9 “I used to tell the pitcher, keep the ball in the park and I’ll catch it. If it goes out of the park, I can’t catch it,” Wilkes said.10

Wilkes’ glove and his speed were major contributions to the 1946 Newark Eagles, the team that won the Negro League World Series. The season started magnificently, as Wilkes saw Day return from the military and throw a no-hitter against the Philadelphia Stars on Opening Day in May. That was an omen of things to come with Day on the mound and Wilkes darting around the outfield. Called a “hustling, never-give-up gang of young ballplayers from across the river,” (in an unknown newspaper account), the Eagles swept the New York Cubans in a doubleheader at the Polo Grounds before 12,000 fans. The sweep pulled the Eagles into a first-place tie with the Philadelphia Stars. “Al [sic] Wilkes, purchased from the United States League last winter by the Manleys, came up with a sensational catch to snag a potential triple to centerfield.”11 Wilkes batted .272 during the season and .280 in the World Series, as Newark defeated the Kansas City Monarchs in seven games.12

In 1947 Wilkes “thrilled the fans last week with one of the greatest catches made a[t] Shibe Park this season.”13 His hitting tailed off to .234 in 1947.14 The season is also synonymous with Jackie Robinson breaking baseball’s color barrier, something Wilkes felt he himself could never have done. “The main reason Rickey signed him was because Jackie had been to UCLA,” Wilkes said. “He’d mingled with the white people. A lot of us wouldn’t have taken the crap Jackie took. Rickey knew Jackie would be a gentleman. What was it Rickey told him? If they smack you on your right cheek, turn your left cheek. I couldn’t have done it.”15

Wilkes played for Newark in 1948 and when the franchise moved to Houston, he played for this relocated Eagles team in 1949, batting .254.

Wilkes has been described this way: “A hustler, he was an excellent defensive player, with outstanding range and a good arm. He had a good eye at the plate, was a pretty good contact hitter, had excellent speed, and was a good base stealer, which made him a good leadoff batter.”16 Twice Wilkes led the Negro Leagues in stolen bases. “Fast, oh yeah,” Wilkes said. “I’d get on first, you might as well put me on second. Just the same as a double.”17

In 1950 Wilkes was invited to spring training with the major-league Dodgers, but they already had a great center fielder named Duke Snider. Wilkes never did make it onto a major-league roster, but he spent 1950-1951 with Dodgers farm teams. Early in 1950, the Monroe (Louisiana) News-Star reported that the new Eagles team in Houston “is captained by Jimmy Wilkes, regarded as the fastest center fielder in Negro baseball.”18 He batted .199 for the Eagles before joining the Elmira Pioneers of the Class-A Eastern League in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ system. His arrival at Elmira was noteworthy, as “the Elmira Star-Gazette reported that Wilkes and outfielder Bob Wilson would be the first two blacks to wear the Pioneers uniform.”19 Wilkes batted .281 during his time with the Pioneers. Later that season, Wilkes also played for the Three Rivers team in the Class-C Canadian American League, where he batted .180.

Wilkes played for Elmira again in 1951, and went 4-for-7 in his first regular-season game.20 The surge of power “Little Jimmy Wilkes” showed surprised writer Jim Morse, who said “‘Mighty Mite’ doesn’t appear to have enough power to hit the ball to the pitcher without the help of a strong wind.”21

Over the course of the 1951 season, Wilkes batted .273 with Elmira in 10 games and .231 with the Lancaster (Pennsylvania) Red Roses of the Interstate League in 105 games. While still with Elmira, Wilkes came through in the clutch with a pinch-hit single with the bases loaded in the 10th inning to give the Pioneers a 4-3 win over Albany.22 In a game for the Roses, Wilkes had a three-run homer and a triple with four RBIs in an 8-2 win over Wilmington.23 On another occasion, Wilkes doubled in the 12th inning and scored the go-ahead run in a game at Allentown at which Connie Mack was present for an old-timers ceremony.24

In 1952 Wilkes played in nine games for the Great Falls (Montana) Electrics of the Class-C Pioneer League, batting .235.

The Dodgers wanted to send Wilkes to their Double-A affiliate in Birmingham, Alabama, but Wilkes refused to play in the South and asked for his release. Growing up in Philadelphia, Wilkes wasn’t used to the segregation he encountered in the Jim Crow South. “I used to hate it when we went barnstorming to the South,” he remembered. “We couldn’t eat in restaurants, had to walk on the other side of the streets and use different water fountains. Being from Philadelphia I hadn’t grown up with all that crap.”

Wilkes continually had to tolerate racial slurs. “Call us black, or whatever, but that word would get everyone angry,” he recalled. “What could you do? Say something and you’d get your head blowed off.”25 “We’d be down there in Mississippi. Oh, boy. Rough, rough. One time, I fouled a ball off my foot. It really hurt and I fell to my knees and someone in the crowd started yelling at me to get up and was using the ‘N’ word. I don’t mind being called black or a Negro, but I don’t like the word nigger. We also had to put up with walking on the other side of the street, back of the buses and crap like that. Even when I got signed with the Dodgers organization, they had to bring the food to me in the bus. We’d eat on the bus and sleep on the bus.”26

After his brief stint with Great Falls, Wilkes returned to the Negro Leagues in 1952 and played for the Indianapolis Clowns of the Negro American League. Despite the name, the Clowns played their home games in Buffalo, New York. As suggested by their name, “[W]hat the Harlem Globetrotters are to basketball, the Clowns are to baseball,” wrote the Buffalo Criterion.27 The Clowns had moved to Buffalo in 1951 and were known for pulling pranks and wearing costumes to entertain the crowd, but they could also play ball with the best teams. “We’d get out there between innings and clown around, but then we had a team that could run you to death,” Wilkes said. “We weren’t clowning then.”28

“We had a tough schedule,” Wilkes remembered of his barnstorming days with the Clowns. “After the ballgame, each time, you’d go to the grocery store and buy some sardines and crackers and hit the bus for the road for the next game. Only time you had a bed was on the weekend, where you’d go into town the night before a doubleheader.”29

While in the Offermann Stadium locker room in Buffalo on May 25, 1952, Milwaukee Braves scout Dewey Griggs asked Wilkes if anybody there could play in the majors. “That fellow sitting in the dugout,” Wilkes responded. “If he doesn’t go to the majors, my name ain’t Jimmy Wilkes.”30

That player was Hank Aaron, an 18-year-old infielder. “I guess you know how that turned out,” Wilkes said almost 50 years later.31

Wilkes hit .325 with 49 stolen bases and 63 runs scored for the Clowns. He was the starting left fielder for the Eastern All-Star team at Comiskey Park in Chicago. Dr. John B. Martin, president of the Negro American League, in his column in the Plaindealer of Kansas City, said, “As a leadoff man, Wilkes is tops in the NAL. He leads the circuit in number of hits, and in stolen bases. He is second in runs scored. He is a fellow the West will have to watch.”32 Wilkes led off for the East team but went 0-for-3 in a 7-3 loss.33

“I could move, brother, they didn’t call me Sea Biscuit for nothing,” Wilkes said in 1997, remembering his days patrolling center field. “If I bunted a ball and it hopped twice, they might as well put the ball in their pocket.”34

Wilkes saw the highs and lows of the Negro Leagues and its eventual demise after African-Americans left for opportunities in the major leagues. “The biggest crowd I ever played in front of was 70,000 people,” he said. “Towards the end there were 1,000 or 1,500 fans in the stands. It was sad. Clubs just started folding because they weren’t making money. It was like the bottom dropped out, like a bucket dropping into a well when you want to get water. But the bucket didn’t come up no more.”35

While on a barnstorming tour in Ontario, Wilkes was discovered by the management of the Brantford Red Sox in the Intercounty League. “I went 5-for-5. The local people liked me. I told them I was tired of riding around the country and if they were interested they should call me,” Wilkes remembered. Team owner Larry Pennell offered Wilkes an immediate contract to come north. The Brantford team was able to lure Wilkes with the promise of a city public-works job during the day and $500 a month to play baseball at night and on weekends. Tired of the racism he faced in the Southern U.S., Wilkes saw Canada as a great opportunity. “They phoned over the winter and I came up in 1953. Opportunity only knocks once and if you don’t take advantage it never comes again.”36

Many African-American players left for Canada to play semipro baseball once the Negro Leagues began folding. Wilkes found both a job and a baseball team in Brantford, and while many players returned to the United States once their playing days were over, Wilkes became a Canadian citizen and spent the rest of his life there. “It was a new experience living here,” he said. “It was God’s country, that’s all I can say. I didn’t have any trouble like I had down in the States, no racial things. I was always surprised how well people liked us. They always treated me well.”37

Wilkes’ job with the city involved driving a street sweeper in the summer, and “in the winter I’d plow snow. One guy I had a beef with, I cleaned the whole street, parked down the street and saw him come out in the morning to see all the snow in his drive. I cleaned it out later.”38

Wilkes played for the Brantford Red Sox from 1953 to 1963 and was a part of five straight titles from 1959 to 1963. “We had ballplayers that knew what to do,” he said. “All our manager had to do was make up the lineup and say, ‘Let’s play ball.’”39 The 1961 Brantford Red Sox went 30-4 with an .882 winning percentage.

Wilkes recalled, “I played until 1963 and when I retired they gave me a night. I was making money playing in Brantford but when the fans give you something you really appreciate it.”40

During his seasons in Canada, Wilkes led the Intercounty League in hits, doubles, runs, and walks in 1956; runs scored in 1961 and 1963; and stolen bases in 1960. His impact on the team and its community was such that “he had his uniform number (5) retired and he was inducted into the City of Brantford’s Hall of Fame.”41

On March 24, 1979, Wilkes married Donna Newton in Brantford. It is unknown if his first wife was deceased, or if the couple had divorced.

Wilkes followed his playing career with a 26-year umpiring career, becoming one of the most respected and sought-after umpires in the league. “I loved being behind home plate,” he said. “That’s where all the action is.”42 He finally retired in 1988.

Wilkes worked in the Brantford Public Works Department for 34½ years. Kids would run outside when they heard his garbage truck or snowplow coming down the street and would shout and wave to him. The man once called Seabiscuit for his blazing speed was now called Yogi Bear by neighborhood children. Wilkes even had “Yogi” inscribed on his license plate.”43

Wilkes also delivered prescriptions to area seniors for Shopper’s Drug Mart in West Brant. “When they answered the doorbell they were always happy to see Jimmy standing there, ready to talk and to listen. His positive attitude and friendly smile probably did more for their general health than the pills he was delivering,” wrote Ted Beare of the Brantford Expositor, noting that Wilkes’ friendly chats often made him late for his next delivery.44

Wilkes also belonged to the Echo Lanes Seniors Monday Bowling League. When he wasn’t bowling he loved to watch the Toronto Blue Jays on TV, or he would care for the birds around his house, even feeding chipmunks and squirrels out of his hand. He also spent time watching his stepsons and grandsons play baseball.45

Making at the most $500 a month in his playing days, Wilkes had trouble comprehending the baseball salaries of modern-day players. “We went hell for those guys playing today. They’re making all that money,” Wilkes said. “We played for the love of the game. I don’t care who the player is, not one player is worth the money they earn.”46

Wilkes remembered those days through the courtesy of old newspaper clippings he kept, which he shared with Michael Snyder of Maclean’s magazine in 2001. “There’s Paige,” he pointed out. “Satchel struck me out three times in a row. He was tall. He’d step down on top of you and boom! The ball would be right there. And Josh. Josh Gibson. He was the Babe Ruth in our league. He could hit ’em a long way. If they would have broke the colour line earlier, he would have broke all kinds of records in home runs.”47 In his Hall of Fame questionnaire, Wilkes listed the greatest accomplishment of his career as getting four hits off Satchel Paige.48

Wilkes suffered with Alzheimer’s disease in the last years of his life. He was interviewed by Tim Graham of the Buffalo News, “aided by a dog-eared scrapbook and gentle reminders from his proud wife. He had trouble recognizing a few photos, even of himself, without looking at the names written on the back.”49 While his memories faded, the scrapbook told an amazing story of his life and the people he knew from Philadelphia to Canada … the buses he rode … the bases he stole … and the children who waved … the man known as Seabiscuit.

Jimmy Wilkes died on August 11, 2008, in Brantford, Ontario, at the age of 82. He was cremated and a tree was planted in his memory at the Beckett-Glaves Memorial Forest.50

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also consulted:

Martin, Alfred M., and Alfred T. Martin. “James (Jimmy) Wilkes” in The Negro Leagues in New Jersey: A History (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2008), 63-64.

Notes

1 Bob Elliott, “Wilkes Has Seen It All,” Toronto Sun, April 20, 1997. Story reprinted on the Western Canada website, retrieved August 14, 2015. attheplate.com/wcbl/profile_wilkes_jimmy.html.

2 Sean Peter Kirst, “Baseball Celebrates; Something’s Missing,” in The Ashes of Lou Gehrig and Other Essays (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 95.

3 Kirst, 96.

4 Kirst, 97.

5 Ted Beare, “Red Sox Star Loved City,” Brantford (Ontario) Expositor, August 11, 2008. Story reprinted on the Western Canada website, retrieved August 14, 2015. attheplate.com/wcbl/profile_wilkes_jimmy.html.

6 Ibid.

7 Ken Hay, “Bartram Wins Public High Title,” The Jay-Bee (Philadelphia), June 4, 1943. Article in Wilkes’ Hall of Fame file.

8 Donna Wilkes, interview with the author, October 26, 2015.

9 Bob Luke, The Most Famous Woman in Baseball: Effa Manley and the Negro Leagues (Washington: Potomac Books, 2011), 112; Thom Loverro, “Brooklyn Brown Dodgers,” in The Encyclopedia of Negro League Baseball (New York: Facts On File, Inc., 2003). African-American History Online. Facts On File, fofweb.com/activelink2.asp?

ItemID=WE01&iPin=ENLB0311&SingleRecord=True (accessed August 18, 2015).

10 “Remembering Jimmy ‘Seabiscuit’ Wilkes,” published online August 16, 2008, from wire reports. blackathlete.net/2008/08/remembering-jimmy-seabiscuit-wilkes/, retrieved August 14, 2015.

11 “Newark Eagles Sweep Both Games With Cubans at PG,” article of unknown origin in Wilkes’ Hall of Fame file.

12 Later in life, Wilkes took credit for a game-saving catch in Game 7. “We were leading them,” Wilkes recalled. “They had two men on, and Buck O’Neil was at bat. He hit a ball high, to left center, for sure it would have been a triple, and I went and got it. He said to me after, ‘You little sonuvabitch. You won the World Series for them.’ That’s why they put me out there. If it was in the ball park, I’d get it.” The story was told to Michael Snider for Maclean’s magazine in 2001. The story was also recounted by O’Neil in a Wilkes obituary. “Wilkes caught the ball with his back to the infield, just like Mays,” said O’Neil. “The entire season came down to that play.” Thanks to research provided by SABR member Frederick C. Bush, however, there are major gaps in this story. For one, O’Neil, in his autobiography, states that Leon Day made the catch to rob him of a hit. This detail is supported by Monte Irvin, who in his autobiography recalled that Day started Game 6 as the pitcher but later moved to the outfield. The Pittsburgh Courier also reported a much different ending to Game 7, stating that it was Kansas City’s Herb Souell who flied out to Newark’s Lennie Pearson to end the Eagles’ 3-2 series-clinching victory after the Monarchs had put runners on first and second with two outs in the top of the ninth inning. In summary, the best research seems to show the catch would have occurred in Game 6, and it was made by Day, not Wilkes, Whether Wilkes intentionally took credit for the catch or, as O’Neil possibly did, confused this catch with another catch, is unknown. For Wilkes’ version of the catch, see “Remembering Jimmy ‘Seabiscuit’ Wilkes,” and Michael Snider, “God’s Country: Former Negro League Players Found Their Fields of Dreams in Small Towns Across Canada,” Maclean’s 114, no. 20 (2001): 37. Academic Search Complete, EBSCOhost (accessed August 17, 2015). For the various accounts that dispute Wilkes’ version, see the following: Buck O’Neil, I Was Right on Time (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996), 178-79; Monte Irvin, Nice Guys Finish First (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc., 1996), 106; and “Newark Eagles New Diamond Champs: Win World Series from Kansas City,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 5, 1946: 15.

13 “Larry Doby, New Home Run Sensation, Faces Stars Under Arcs Thursday,” article of unknown origin in Wilkes’ Hall of Fame file.

14 Numbers vary according to source. These were taken from the Biographical Encyclopedia of the Negro Baseball Leagues, coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/wilkes.html.

15 Bob Elliott, “Jackie Robinson Became the Major Leagues’ First Black Player on This Day In 1947 and, for Jimmy Wilkes of Brantford, the Memories Remain Vivid,” Toronto Sun, April 15, 1997.

16 “Jimmy Wilkes,” in Negro League Baseball Museum website,

coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/wilkes.html, retrieved August 17, 2015.

17 Snider, “God’s Country,”

18 “Black Yanks Meet Houston Tomorrow,” Monroe (Louisiana) News-Star, April 25, 1950: 10.

19 Barry Swanton and Jay-Dell Mah, Black Baseball Players in Canada: A Biographical Dictionary, 1881-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, Inc., 2009), 178.

20 Jim Morse, “Fallon Relieves Mulleavy of Pilot’s Duties Today,” article of unknown origin in Wilkes’ Hall of Fame file.

21 Jim Morse, unknown article in Wilkes’ Hall of Fame file.

22 Jim Morse, “Jim Wilkes’ Pinch Single Gives Stanek 3rd Win; Hugh Mulcahy to Pitch Tonight,” article of unknown origin labeled May 21, 1951, in Wilkes’ Hall of Fame file.

23 “Roses Home to Fight for Second,” article of unknown origin in Wilkes’ Hall of Fame file.

24 “Steen Hurls Roses to Win Over Cards,” article of unknown origin in Wilkes’ Hall of Fame file.

25 Elliott, “Jackie Robinson Became the Major Leagues’ First Black Player.”

26 Snider.

27 “Clowns, Memphis Red Sox Open Negro League Baseball Sun. May 25, 2 p.m.,” Buffalo Criterion, May 10, 1952. Reprinted on the “Baseball Games” website, baseballgames.dreamhosters.com/NegroLeaguesBuffalo.htm.

Retrieved August 16, 2015.

28 “Class Clowns.”

29 Snider.

30 Elliott, “Wilkes Has Seen It All.”

31 Tim Graham, “Class Clowns: The Indianapolis Clowns Have a Rich Place in Buffalo Baseball History; for Example Hank Aaron Was ‘Discovered’ at Offermann Stadium,” Buffalo News, September 22, 2004. Story reprinted on “Baseball Games,” website, baseballgames.dreamhosters.com/NegroLeaguesBuffalo.htm. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

32 Dr. J.B. Martin, “Dr Martin Says: East-West Classic Time Is Here,” Plaindealer (Kansas City, Kansas), August 15, 1952: 5.

33 “West Nips East, 7-3, in Negro Game,” Chicago Tribune, August 18, 1952.

34 Bob Elliott, “Jackie Robinson Became the Major Leagues’ First Black Player.”

35 “Class Clowns.”

36 William Humber, A Sporting Chance: Achievements of African-Canadian Athletes (Toronto: Natural Heritage Books, 2004), 58.

37 Snider.

38 Elliott, “Jackie Robinson Became the Major Leagues’ First Black Player.”

39 Paul Ferguson, “Toronto Maple Leaf Baseball,” Toronto Sun, August 4, 2001. Story reprinted on the Western Canada website, retrieved August 14, 2015. attheplate.com/wcbl/profile_wilkes_jimmy.html.

40 Humber, 58-59.

41 Swanton and Mah, 179.

42 Paul Patton, “Where Are They Now? Jim Wilkes Baseball,” Globe and Mail (Toronto), March 5, 1988. search.proquest.com/docview/385954599?accountid=14612.

43 Beare, “Red Sox Star Loved City.”

44 Ibid.

45 “James Wilkes,” yourlifemoments.ca/sitepages/obituary.asp?oId=256573, retrieved August 18, 2015.

46 Elliott, “Jackie Robinson Became the Major Leagues’ First Black Player.”

47 Snider.

48 Jimmy Wilkes’ Baseball Hall of Fame questionnaire.

49 “Class Clowns.”

50 “James ‘Jimmy’ Eugene Wilkes Obituary,” retrieved from obitsforlife.com/obituary/95253/Wilkes-James.php, August 5, 2015.

Full Name

James Eugene Wilkes

Born

October 1, 1925 at Philadelphia, PA (US)

Died

August 11, 2008 at Brantford, ON (CA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.