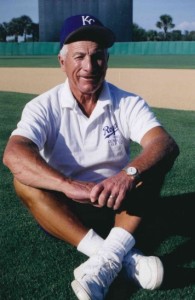

George Toma

Former Cleveland Indians and St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck once said, “A good groundskeeper was the 10th man on the field and was worth five to seven victories a season.”1 George Toma is often ranked among the greatest groundskeepers of all time, creating and maintaining professional baseball, football, soccer, and Olympic playing fields all over the world.2

Former Cleveland Indians and St. Louis Browns owner Bill Veeck once said, “A good groundskeeper was the 10th man on the field and was worth five to seven victories a season.”1 George Toma is often ranked among the greatest groundskeepers of all time, creating and maintaining professional baseball, football, soccer, and Olympic playing fields all over the world.2

His work philosophy was simple: Work as hard as you can, and then try to do a little more. He once noted that “the cheapest insurance for an athlete is a good, safe playing field.” Toma believed sports fields could be maintained inexpensively in a way that could be beneficial for both the players and the team owners.3

Nicknamed the “nitty gritty dirt man” and/or the “sod god,” by both the players and the baseball press, Toma was born February 2, 1929, in Edwardsville, a small, poor coal-mining town in Pennsylvania.4

His father worked as a breaker in a coal mine but died of black-lung disease when George was 10. To help address the financial challenges his family now faced, he began working at a tomato farm.5

At 5-feet-4, he felt he was too small to play baseball. Toma’s interest in groundskeeping may have started when he and his friends annually cleared an area near his house to play sports. As part of the clearing process, they would use the springs from discarded mattresses and then drag/pull them by hand to smooth into a makeshift playing field.6

One of George’s neighbors was a groundskeeper at Artillery Park for the Wilkes-Barre Barons of the Class-A Eastern League. When George’s father died, his neighbor began taking Toma with him to help drag the infield.

When Bill Veeck became the owner of the Cleveland Indians and their farm system, he also became the Barons owner. He changed the club’s name to the Indians. He also made a few cost-cutting moves, including making Toma the new head groundskeeper. Veeck also sent George to work with Emil Bossard, the Indians’ head groundskeeper, who was nationally known for his groundskeeping acumen.7

From 1951 to 1953, Toma served in the US Army, deploying to Korea. After his discharge he resumed his job as the head groundskeeper for the Barons, continuing his excellent work at Wilkes-Barre. More importantly, his work was noticed by several major- and high-level minor-league clubs.

In 1955 Toma became the head groundskeeper for Buffalo, the Triple-A club for the Detroit Tigers. When Detroit moved the club to Charleston, West Virginia, Toma followed the club. In 1957 he got two head groundskeeper offers: the Yankees’ Triple-A affiliate in Denver and the Kansas City Athletics’ major-league club. Many of his friends, including Bossard, urged him to take the Denver offer. Kansas City’s field had a reputation of being horrible. Looking to his future, Toma expected to eventually advance to Yankee Stadium. However, he knew he would not like living under the microscope in New York. Toma went to both Kansas City and Denver to look over their fields. Kansas City’s field was, as rumored, horrible.

He went back to Charleston and received some sage advice from one of the club officials. “George, the best thing for you to do is to go to Kansas City. If you screw up, nobody will notice it’s so bad.” Toma took his advice, called Kansas City, and took the job.8

In 1955 former President Harry Truman threw out the first pitch at Kansas City’s Municipal Stadium. By the time Toma took over as head groundskeeper, it had significantly deteriorated. The stadium was a mess and the infield posed a real danger to the players.

Toma and his staff of one other groundskeeper started with one Toro professional lawnmower, an airifier, and an International tractor. They gathered up broken seats and discarded items from concession stands and took it all to a local junkyard. With the money they got for the junk, they bought fertilizer and manure. Under the constant care of Toma, by the next spring Municipal Stadium’s field became a yardstick for measuring infield/outfield quality.

Charles O. Finley was one of most despised baseball club owners in baseball history. Yet Toma considered Finley the finest owner he ever worked for. Toma was impressed by Finley’s compassion when the owner gave him a $3,000 gift to celebrate the birth of George’s new son.

Finley was also a little eccentric/crazy and liked a good joke. In particular, he liked animals and established a small zoo near the Municipal Stadium fence. He stocked his field with a mule (Charlie O), monkeys, pheasants, rabbits, and sheep. The groundskeepers had to maintain all of them, including spray-painting the sheep different colors.

In addition, there were pregame water fights between the Athletics groundskeepers and several Yankees players. Finley even bought some perfume and had Toma spread it through the Yankees dugout to irritate their players.

At the end of 1967, Finley moved the Athletics to Oakland, where they prospered. They won three consecutive World Series (1972-1974). Then Finley did something extraordinary. He gave Toma an Oakland A’ s Championship ring with a clover leaf, the years ’72,’73, and ’74, three S’s for sweat and sacrifice equals success, and Toma’s name on it.9

In 1963, Lamar Hunt moved the Dallas Texans to Kansas City where they became the Kansas City Chiefs and would also occupy Municipal Stadium. When Hunt first visited Municipal Stadium, Toma was on top of the center-field flagpole giving it a fresh coat of paint. Toma did not like anyone walking on his field and yelled at Hunt and his party to get off his field.

The transition from baseball to football was not always smooth, as both Finley and Hunt had strong personalities. Trying to irritate Hunt and perhaps trying to get Toma to join him in Oakland, Finley ended up paying the remainder of Toma’s 1963 salary if he would totally stay away from Municipal Stadium. During his time off, Toma received and executed several short-term baseball and/or football-field turf-related consulting jobs. One of his assignments was field preparation work for the annual Thanksgiving Day game at the Cotton Bowl. His work drew praise from NFL Commissioner Pete Rozelle.

Based on Toma’s Cotton Bowl success, the NFL and the AFL chose him to prepare the Los Angeles Coliseum for the first NFL-AFL championship game. (This game became the Super Bowl.)

One of Toma’s favorite Super Bowl memories was when Emmitt Smith of the Dallas Cowboys came by after practice for Super Bowl XXX and asked him to autograph a piece of sod that he was going to put down in his front yard. Over his career, Toma ended up handling the field prep work for 50 Super Bowls. The NFL also contracted with him to do and/or supervise all the field prep work for 37 Pro Bowls.

The NFL also used Toma’s field preparation expertise for special American Bowls held in various international cities, including London, Tokyo, and Mexico City.10

In 1969 Toma was named head groundskeeper for the Royals and Royals (later Kaufmann) Stadium. He also maintained his position with the Chiefs and was named the director of landscaping at the Harry S. Truman Sports Complex.

Toma’s position also led to him meeting and marrying his wife, Donna, also an avid baseball fan. He credited the Royals’ bullpen pitchers and catchers with helping his young son to learn how to walk and potty-training him.

One of the highlights of Toma’s baseball career was watching the Royals beat the Cardinals to win the 1985 World Series. During the postgame celebration, as the fans streamed across the field, his youngest son began to cry, “Get off my daddy’s field!”11

Toma also oversaw the infield preparations for Summer Olympics held in the Los Angeles Coliseum (1994) and Atlanta’s Olympic Stadium (1996). In Atlanta, their sod was dead in the area where the opening ceremonies were to take place. Olympic officials contacted Toma immediately and he led the installation of 13,500 cubic yards of sod in 24 hours with 12 hours of sod-bed preparation. After the job was finished, an exhausted Toma fell asleep in Chipper Jones’s locker.12

In 2000 Toma was asked to “salvage” Hammond Stadium in Fort Myers, Florida. Worms had chewed up the roots of the grass. In eight days, the field was to be used for the Florida State League All-Star Game. Toma and his crew had to take out the infield and outfield grass, fill the hole back up with a mixture of sand and peat moss, grade it, water it down, and then put high-quality sod over it. The job was done in eight days and the field drew praise from league management and the players. His work was also noticed by the Minnesota Twins, who used him to annually help prepare their spring training practice fields in Florida.13

In addition to his football and baseball field expertise, he assisted in the field preparation for various World Cup venues, particularly Soldier Field in Chicago and the Silverdome in Pontiac, Michigan.

Over the years, Toma’s field preparation work has resulted in many awards and accolades. In 2001 he received the Dan Reeves Pioneer Award at the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio. He is also in the Kansas City Royals Hall of Fame and the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame, and has received numerous awards from the Sports Turf Managers Association. STMA named one its annual awards after him: the George Toma Gold Rake Award.14

When asked about the seemingly minor role as a groundskeeper, Toma would describe what was under the Chiefs’ Arrowhead Stadium: five miles of electrical conduit, two miles of drainage pipe, and one mile of irrigation pipe. Layered over the subsurface is a 4-inch pea gravel base topped by a 12-inch root zone. The root zone comprises 5,000 tons of 85 percent regular sand, and 15 percent reed sedge peat. Then comes choosing the right mixture of grass to put down as the playing surface. “I’m just nobody,” Toma once said. “But I appreciate a good field.”

Notes

1 George Toma with Alan Goforth, Nitty Gritty Dirt Man (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, 2004), 181.

2 Ibid.

3 Missouri Sports Hall of Fame Inductee, George Toma, mosportshalloffame.com/inductees/5327/

4 Toma with Goforth, 5.

5 Toma with Goforth, 6.

6 Toma with Goforth, 12-13.

7 Toma with Goforth, 16-32.

8 Toma with Goforth, 28-32.

9 Toma with Goforth, 35-44.

10 Missouri Sports Hall of Fame, George Toma.

11 Toma with Goforth, 69-78.

12 Toma with Goforth, 110.

13 David Dorsey, “George Toma: Super Bowl ‘Sod God’ Rakes It Easy in Fort Myers,” Fort Myers (Florida) News-Press, March 21, 2017. news-press.com/story/sports/2017/03/21/george-toma-god-hammond-stadiums-sod/98948536/

14 Kevin Burrows, “George Toma: From Single A to the Superbowl. … and Then Some,” landscapeonline.com/research/article-a.php?number=11137.

Full Name

George Toma

Born

February 2, 1929 at Edwardsville, PA (US)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.