1883 Philadelphia Athletics: The Postseason Matchup That Wasn’t

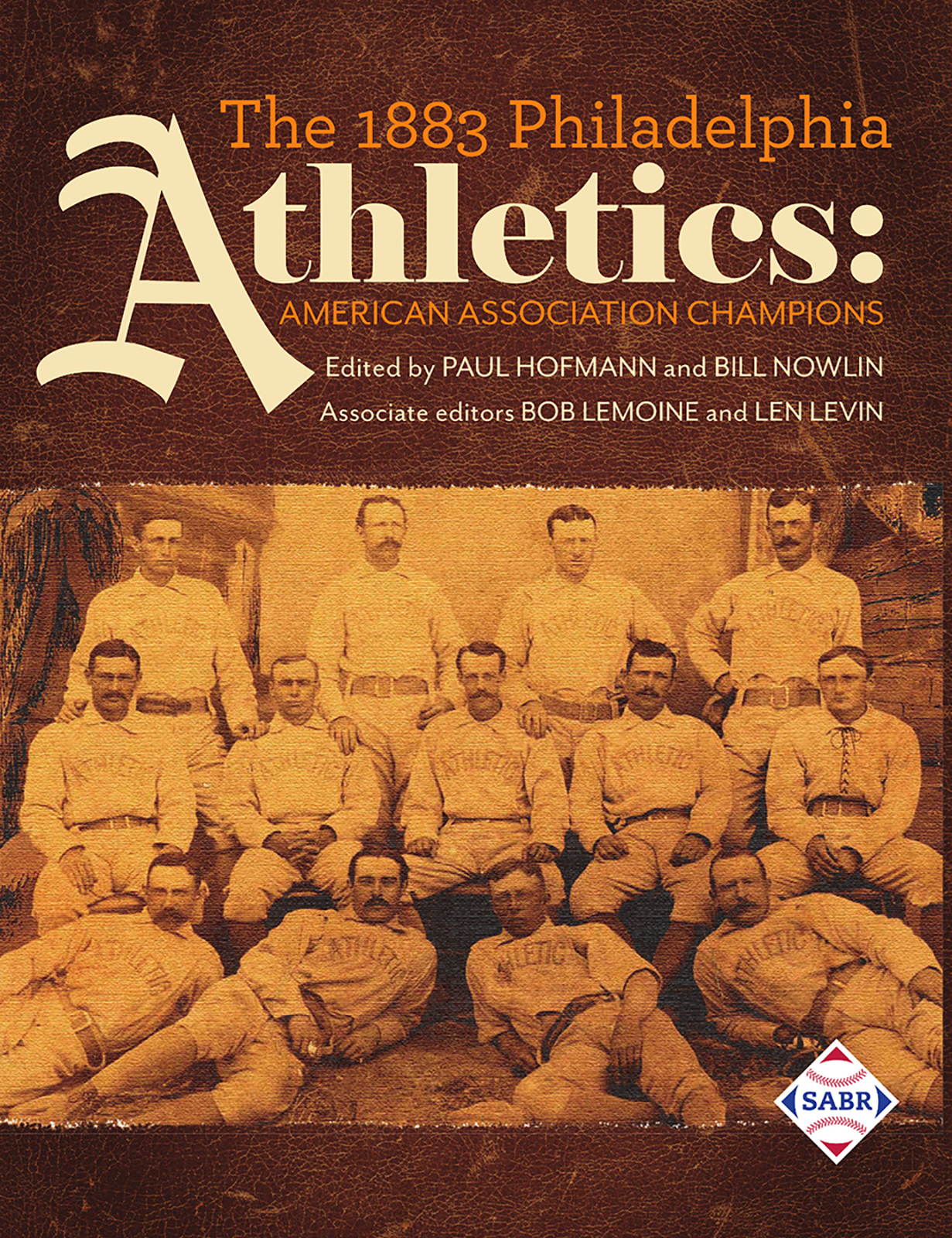

This article appears in SABR’s “The 1883 Philadelphia Athletics: American Association Champions” (2022), edited by Paul Hofmann and Bill Nowlin.

The Philadelphia Athletics clinched the 1883 American Association championship on September 28. For five days the Quaker city had nervously watched their team’s lead over the St. Louis Browns shrink, but with just one game left to play, the Philadelphias put away the pesky Louisville Eclipse and claimed their first baseball championship. Four days later the city celebrated as never before. The team “was attended with reception ceremonies unprecedented in the history of the national game.”1 A brass band played as the team arrived back home, 10,000 cheered as their heroes got off the train, and a parade followed that “was witnessed by as many people as saw the Grant parade or the Bi-Centennial pageant.”2

The Philadelphia Athletics clinched the 1883 American Association championship on September 28. For five days the Quaker city had nervously watched their team’s lead over the St. Louis Browns shrink, but with just one game left to play, the Philadelphias put away the pesky Louisville Eclipse and claimed their first baseball championship. Four days later the city celebrated as never before. The team “was attended with reception ceremonies unprecedented in the history of the national game.”1 A brass band played as the team arrived back home, 10,000 cheered as their heroes got off the train, and a parade followed that “was witnessed by as many people as saw the Grant parade or the Bi-Centennial pageant.”2

The end of the season signaled the beginning of an exhibition season between National League and American Association teams. For the second year the exhibitions were expected to include a three-game series between the National League champion Boston Beaneaters and the American Association champion Athletics. Spalding’s 1884 Base Ball Guide said the winner of the series would be recognized as champion of the United States.3 The Philadelphia Times went one step further and claimed that the winner would be the North American Champion.4

Two days later, on October 3, the new champions played their first postseason exhibition game, against their hometown rivals, the Phillies. It had been a rough season for the Quaker City’s National League representative. The Phillies ended the campaign deep in the League’s cellar, having lost 81 of the 98 games they played. The two teams were scheduled to play three times. The winner would be recognized as the Philadelphia city champion. After the excitement surrounding the Athletics’ championship as well as the local significance of games, a large, enthusiastic crowd was anticipated. Instead, only between 5,000 and 6,000 fans showed up, far fewer than most expected.

The game that followed was “the slowest and most tedious of the season,” wrote the Philadelphia Times. “There was scarcely any vim displayed by the players and the audience appeared to be in a decidedly comatose state.”5 Through the early innings “errors came thick and fast” but initially the two pitchers dominated play.6 The teams scratched away at each other until a five-run Athletics outburst in the fourth inning put the game away. Despite the uninspired performance, the Athletic players shared half of the game’s gate which came to approximately $50 each.

The next day another disappointing crowd, 2,500, came out to see the Athletics do battle with the Cleveland Blues. Cleveland had finished in fourth place in the National League, 7½ games back of Boston. The game turned into a sloppy 8-7 loss for the home team. Though Philadelphia hit well, “the contest was remarkable for the number of fly balls muffed.”7 In all Philadelphia committed 12 errors. For local fans, the high point of the afternoon came on the day’s last pitch to Cleveland hitters when pitcher finally executed his unique four-foot jumping delivery.

The results a day later were even more discouraging. A crowd of only 2,000 watched “the most humiliating (defeat) sustained by the Athletics this season.”8 While Providence Grays ace Hoss Radbourn held the Athletics scoreless, allowing only three singles, his teammates, with the help of more Philadelphia errors, pummeled the Athletics ace, Bobby Mathews, for 12 runs. It was a very gloomy afternoon for the American Association champions and their fans.

The series with the Phillies resumed three days after the Providence shellacking. Through five innings the Athletics looked like champions again. Athletics pitcher George Bradley held the city rivals to a single run while Athletics hitters scored four times. Then in the sixth, the Phillies broke through with five runs, and two innings later put another two on the board. Meanwhile, the Athletics were blanked and able to scratch out only one hit over the last six innings.

Buffalo added to the Athletics’ woes, trouncing them on three consecutive afternoons, October 9-11. In the first game, the home team was held to just four hits in a 7-1 loss during which “there was not much to amuse the two thousand spectators.”9 In the second meeting, the Bisons put 10 runs on the board before the Athletics scored. Throughout the game “the champions fielded in a slow and easy manner and apparently made no effort to make the contest of interest to the fifteen hundred spectators.”10 The result was a 15-5 drubbing. In the final game, both teams sprinkled their lineups with pickup players and both teams played miserably in the field. It was a different story at the plate. The Bisons roared out to an early five-run lead, which “took all interest out of the game,” then coasted to an easy 9-2 victory.11

After the third loss to Buffalo, the Athletics management decided to cancel the postseason series with Boston even though just a day earlier local papers had reported that the series was still set for October 18, 19, and 20.12 In justifying the decision, a club representative claimed that all the players needed a rest and several “are more or less crippled.”13 In fact, regular starter Ed Rowen had missed two games, Harry Stovey missed three, and Bobby Mathews and Jack O’Brien had missed four of the seven games played. “I don’t want to see them limping around the field and spectators would not make allowances,” the club spokesman said.14

There were additional considerations that went into the Philadelphia decision to cancel the Boston series. Obviously, the steadily shrinking audience meant steadily shrinking revenues and there was no guarantee that even a postseason series would generate more attendance. It was also clear that the Philadelphia players were anxious to rest after a long, hard-fought season. Stovey, the team’s most dangerous hitter, was already headed back to his home in New Bedford, Massachusetts, and four others were scheduled to leave within a few days. Another consideration was the American Association’s reputation. Since its inception in 1882, there were many who questioned the league’s quality of play. During the exhibition season Association teams had not done well against their National League opponents, dropping 37 of the 55 games played. Of course, no Association team had done worse than the league’s champion. The Athletics losses to the lowly Phillies were especially embarrassing. Those who argued that the American Association was an inferior league would be fortified if Philadelphia, playing without several of its best players, was swamped by Boston, which appeared likely to happen. The final factor influencing the decision was the weather. The mild days of autumn were quickly giving way to the approach of winter, further deterring potential attendance.

In Boston the cancellation was greeted with a degree of distain. The previous season the American Association champion Cincinnati Red Stockings had beaten their National League counterpart, the Chicago White Stockings. Defenders of the National League, most notably White Stockings president A.G. Spalding, claimed that the games were merely exhibition games and meant very little. Nevertheless, in its inaugural season of play, the Association’s series victory was a grand success. The Beaneaters, as well as the rest of the National League, were anxious to redeem their League. The cancellation abruptly curtailed the league’s anticipated revenge. “It would have been far more creditable and honorable to have completed the season, no matter how badly beaten, than to have closed the season the way they have.”15

Despite backing out of the series with the Bostons, the Athletics did play one final game against a National League team and it was for a championship. The team was the Phillies, and the championship was the Philadelphia city championship. On a chilly, wet, and windy mid-October afternoon playing in front of only 1,500 fans who “stood about and shivered in the cold, raw wind,” the Athletics, who included a couple of pickup players, lost to the Phillies one last time, 8-3.16

PAUL E. DOUTRICH is professor emeritus at York College of Pennsylvania, where he taught American history for 30 years. He now lives in Brewster, Massachusetts. Among the courses he taught was one entitled Baseball History. He has written scholarly articles and contributed to several anthologies about the Revolutionary era, and has written a book about Jacksonian America. He has also curated several museum exhibits. His recent scholarship has focused on baseball history. He has contributed numerous manuscripts to various SABR publications and is the author of The Cardinals and the Yankees, 1926: A Classical Season and St. Louis in Seven.

Notes

1 “The American Season of 1883,” Spalding’s Official Baseball Guide, 1884: 54.

2 “The Base Ball Parade,” Times (Philadelphia), October 2, 1883: 1.

3 Spalding’s 1884 Base Ball Guide: 58.

4 “Base Ball Notes,” Times, October 11, 1883: 3.

5 “The Athletics at Home,” Times, October 4, 1883: 1.

6 “The Athletics at Home.”

7 “The Champions Beaten,” Times, October 5, 1883: 3.

8 “Twelve to Nothing,” Times, October 6, 1883: 3.

9 “The Athletics Again Beaten,” Times, October 10, 1883: 3.

10 “Beaten Again,” Times, October 11, 1883: 3.

11 “The Last of the Season,” Philadelphia Inquirer, October 12, 1883: 3.

12 “Base Ball Notes,” Times, October 11, 1883: 3.

13 “The Crippled Champs,” Times, October 12, 1883: 1.

14 “The Crippled Champs.”

15 “Diamond Dust,” Boston Globe, October 14, 1883: 6.

16 “Bat and Ball,” Times, October 16, 1883: 4.