A Baseball Myth Exploded: Bill Veeck and the 1943 Sale of the Phillies

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in SABR’s The National Pastime, Vol. 18, in 1998. For additional commentary about this story, read “The Veracity of Veeck,” by Robert D. Warrington and Norman Macht in the Fall 2013 Baseball Research Journal and Warren Corbett’s SABR biography of Bill Veeck.

Baseball is a game in which the line between myth and reality is constantly blurred. The devotees of and participants in this most American of all sports delight n creating stories whose truth is often difficult to un-ravel: Abner Doubleday’s invention of baseball, Pete Alexander’s celebrated hangover in the 1926 World Series, Babe Ruth’s “called shot” home run against the Cubs in 1932.

Baseball is a game in which the line between myth and reality is constantly blurred. The devotees of and participants in this most American of all sports delight n creating stories whose truth is often difficult to un-ravel: Abner Doubleday’s invention of baseball, Pete Alexander’s celebrated hangover in the 1926 World Series, Babe Ruth’s “called shot” home run against the Cubs in 1932.

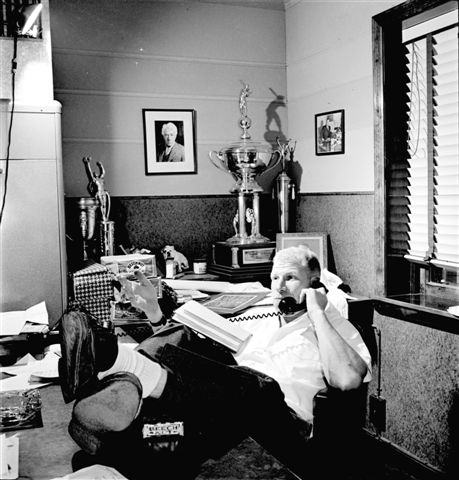

Another classic example of an enduring legend is the tale of Bill Veeck, lovable old Sportshirt Bill, the game’s enfant terrible, arranging to buy the bankrupt Philadelphia Phillies franchise early in World War II. The story, first told by Veeck himself in his 1962 autobiography Veeck-As In Wreck, is that Veeck planned to stock the club with top-notch black ballplayers from he Negro Leagues but was cheated out of his opportunity by the last-minute chicanery of Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, the commissioner, and National League president Ford C. Frick.

The story has been told and retold so many times that it hardly needs citation to a source any more. It has become an article of historical faith, found in virtually every general history of black and white professional baseball as well as in studies of racial integration.1 Veeck’s most recent biographer goes into some detail about the alleged purchase of the Philadelphia club, although he includes some startling divergences from Veeck’s own story.2 A recently published work called The Phillies Reader reprints Veeck’s tale verbatim without the slightest indication that there might be some question about its accuracy, except for a slight mixup in the year.3 The Los Angeles Times columnist Jim Murray wrote a piece entitled “The `42 Phils That Weren’t” which swallowed Veeck’s story whole and even added embellishments of his own.4

The major difficulty with this oft-told story is that it is not true. Veeck did not have a deal to buy the Phillies. He did not work with Abe Saperstein and others to stock any team with Negro Leagues stars. No such deal was quashed by Landis or Frick. In fact, there was hardly any Veeck-Phillies connection at all.

This all becomes clear when we examine the record of what happened with and to the Phillies in the 1942-43 offseason. A review of the press coverage and what Veeck himself said at the time of his subsequent purchase of the Cleveland Indians furnishes further evidence, like Sherlock Holmes’s nonbarking dog, of what did not happen in early 1943.

Let’s start by examining the Phillies’ situation in the 1942-43 offseason and what the National League, through its owners and its president, did about it, as well as what the baseball press wrote about the situation.

The pathetic Phillies

As the 1942 season came to an end, Gerald P. Nugent’s Phillies were found in their customary spot, last place, for the fifth year in a row. With a record of 42 wins and 109 defeats, the Phils under manager John “Hans” Lobert finished 18-1/2 games behind the seventh-place Boston Braves and 62-1/2 behind the pennant-winning Cardinals. Home attendance for the season was a sad 230,183, and the wonder is that that many people came to see them in that first wartime season. On September 11, only 393 people showed up at Shibe Park to watch the Phils lose to Cincinnati. The pitching staff’s earned run average was the highest in the National League, and the team’s anemic .232 batting average was the worst in its history.

With the dreadful 1942 Phillies, the National League had finally had enough. For year after year the underfunded Philadelphia franchise had been a drag on the league. Most of the time a visiting club failed to make enough from a series in Philadelphia to cover its costs. Even the 1938 change from musty old Baker Bowl to Shibe Park had not improved the Phillies’ fortunes.

Gerry Nugent was a savvy baseball executive, but he had no money and for years had performed feats of financial legerdemain simply to keep the club afloat. Now he had just about run out of options. He was in debt to the league, after an advance that had enabled the team to go to spring training in 1942, and in arrears for the rent owed to the Athletics, who owned Shibe Park. The Philadelphia Inquirer’s Stan Baumgartner calculated that the club owed a total of $330,000.5 With an average attendance of fewer than 3,000 fans per game, there was little prospect of salvation. For years, Nugent had peddled whatever competent players he came up with in order to meet day-to-day expenses. He planned, in the `42-’43 offseason, to sell Danny Litwhiler, Tommy Hughes, and Ike Pearson, the best of the sorry lot of 1942 Phils, to the highest bidders. The National League, as his creditor, with a lien upon his assets, now restrained him from doing this.6

League action

Early in November the National League owners met, at Nugent’s request, to hear the Phillies’ problems laid out in detail. The Associated Press then reported that “sale of the… [club] now is certain this winter and possibly within a few weeks.” League president Ford Frick denied that any definite action had been settled on, but when asked if the league would lend Nugent more money Frick replied, “Absolutely no.”7

Early in December, at the major league meetings in Chicago, the National League devoted a full day to “threshing out its biggest problem, what to do with the Philadelphia Phils.” Nugent and his lawyer sat out in the hall while his fellow moguls deliberated. Nothing was decided, and the problem was dumped back into Nugent’s lap. He was told to go back to Philadelphia and find a well-heeled buyer. He said he was “willing to sell my stock to a suitable buyer who would have enough capital to build the Phils. As I understand it, no such potential buyer has been uncovered.”8

On February 1, 1943, Nugent told the press that rumors of the league taking the team from him were unfounded. “Certainly,” he said, “nobody can come in and take the club without buying it.” His lawyer had assured him of that. Unfortunately, Nugent had been unable to find a qualified buyer. Another league meeting was called for February 9, at which it was expected some sort of resolution would be reached.9

At this meeting, things came to a head. The National League purchased “substantially all” of the club stock from Gerry Nugent and other stockholders for whom he acted “at an agreed price” of $10 a share for 2,600 shares, plus the assumption of the club’s estimated $300,000 debt, more than a third of which was owed to the league itself. Although Red Smith in the Philadelphia Record said “the Phils were sold out from under” Nugent, and Ed Pollock in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin said the league had given him “what amounts to a dignified `bum’s rush’,” the Phils’ owner himself said he was “entirely satisfied” with the league’s action. A week or so later, a syndicate put together by lumber broker William D. Cox, a wealthy New Yorker out of Yale, purchased the Phillies from the National League for approximately $250,000. On paper, Cox and his group looked like just the sort of well-endowed ownership that the Phillies had long needed, but within a year Cox himself had been booted from the game by Judge Landis.10

This resolution of the Nugent-Phillies problem was obviously not a hasty action on the part of the National League. At least since November, 1942, if not earlier, the groundwork was being laid for Gerry Nugent to sell his franchise back to the league if he was unable to locate a qualified purchaser. Nugent knew it, the other owners knew it, and the members of the press covering the Phillies knew that such a step was a likely outcome of a situation that had become impossible.

Veeck’s story

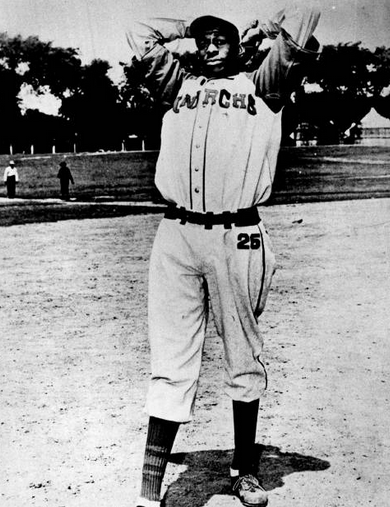

It was during this period that Veeck, at the time the flamboyant owner of the minor league Milwaukee Brewers, later claimed he attempted to purchase the team with the intent of breaking Organized Baseball’s long-standing color barrier. In his autobiography, Veeck says he made an offer to Nugent to buy the club, planning to “stock it with Negro players,” and that “he [Nugent] had expressed a willingness to accept” the offer. The players, Veeck says, “were going to be assembled for me by Abe Saperstein and [A.S.] “Doc” Young, the sports editor of the Chicago Defender, two of the most knowledgeable men in the country on the subject of Negro baseball.” He goes on to say that with performers like Satchel Paige, Roy Campanella, Luke Easter, Monte Irvin, and many others “in action and available, I had not the slightest doubt that in 1944, a war year, the Phils would have leaped from seventh place to the pennant.”

Veeck says he “made one bad mistake.” Out of respect he told Judge Landis what he was planning to do. “Judge Landis wasn’t exactly shocked but he wasn’t exactly overjoyed either. His first reaction, in fact, was that I was kidding him.. .The next thing I knew,” Veeck says, he learned that the National League had taken over the team and that Frick found a buyer who paid half what Veeck was offering.

Veeck asserts that “the CIO was ready and eager to give me all the financing I needed. The money, in fact, was already escrowed.” Unfortunately, the CIO official with whom Veeck was dealing did not want his name to “enter into any of the publicity,” and twenty years later Veeck, with rare delicacy, was still respecting that desire for anonymity, even at the cost of frustrating those who might want to check out his story. He had “another potential — and logical — backer, Phillies Cigars.” This was, presumably, the Bayuk Company, which manufactured the cigars, but this organization, too, lost out on its chance to help Veeck buy the Phillies.11

There are many problems with Veeck’s recital. The main one is that it has never been corroborated by anyone else. Although the story shows up in many accounts of the eventual racial integration of baseball, the source always turns out to be either the two pages from Veeck’s autobiography or an interview with Veeck himself.12 Another is that it defies economic logic. If such an offer had been on the table, Nugent would certainly not have yielded up his franchise to Frick and the National League, saying he was “entirely satisfied,” to get half of what Veeck later claimed he had offered. Nugent was quite aware that the league could not legally take his team away from him, and Nugent’s livelihood depended on the Phillies. If he sold the club, he needed to get the best price possible. In fact, Nugent was given the period from November to early February to develop just the kind of offer Veeck claims to have made him, and he was unable to do so.

The Veeck-Nugent meeting

During the `42 World Series, a reporter with some space to fill concocted a rumor, denied immediately by Nugent, that Veeck had offered to buy the Phils. Veeck said this report gave him an idea. He, with Rudie Schaffer, his righthand man, stopped to see Nugent in Philadelphia after the Series. “We talked about his club,” Veeck told the Milwaukee Journal. “He quoted some large figures, of course, but that was all.” Schaffer has told one of the authors of this article that the meeting “wasn’t a very productive one.” He and Veeck went back to Milwaukee, and Schaffer knew of no further contacts between Veeck and Nugent. In fact, that was all.13

In November, 1942, Stan Baumgartner had asked Nugent about Veeck. The Phillies’ owner, after saying, “Any person who comes to me with a worthwhile bid and has money to back it up can have the club, or at least my share in it,” went on to say:

During the past year it was published that Bill Veeck, head of the Milwaukee club, had, or would make an offer for the Phils. Veeck stopped in to see me on his way [sic] to the World’s Series and did not mention buying or even being interested in the club. When he got back home I saw a clipping from a Milwaukee paper which quoted Veeck as saying he had stopped in to see me because he had read that he was interested in buying the club — and he wanted to see what it was all about.14

One can certainly see in this simply another version of the same meeting that Veeck described to the Milwaukee writers and that Rudie Schaffer described: casual conversation with Nugent about the Phillies ballclub but nothing more.

Veeck’s October meeting was mentioned in the November 12 Inquirer, but never again, from that time to the unveiling of the new owner on February 20, 1943, did Veeck’s name appear again in the Philadelphia papers in speculation about a possible buyer. Branch Rickey was mentioned, until he took a new job with the Dodgers. Former Postmaster General Jim Farley was mentioned. Several Philadelphia prospects were mentioned, including the brickwork mogul, John B. Kelly, father of future movie queen and Monagasque princess Grace Kelly. A couple of groups from Baltimore, who wanted to move the franchise there, were mentioned. Bill Veeck was not mentioned once in this connection.

The African American media

Significantly, the Philadelphia Tribune, the city’s leading black newspaper, never wrote a word about the sale of the Phillies in this period, either before or after the departure of Gerry Nugent, indicating by its silence that the fate of the ball club was a matter of indifference to its readers.15 The Tribune’s silence also indicates, of course, that its editors and reporters had never picked up anything about Veeck’s alleged intentions, although the CIO and the Bayuk people and Young, at least, supposedly knew of them. Nor did the usually garrulous Veeck say anything further about the Phillies’ situation to his sportswriters in Milwaukee.16

The silence of the Philadelphia Tribune and other leading black newspapers on a possible sale of the Phillies to Veeck and its frustration by Landis and/or Frick is significant. By 1942 African American sportswriters had become increasingly vocal and persistent in pressing for the racial integration of Organized Baseball as part of the overall assault on segregation in America. Led by Wendell Smith of the Pittsburgh Courier, Sam Lacy of the Baltimore Afro American, Joe Bostic of New York’s The People’s Voice, and Fay Young of the Chicago Defender, they were pointedly critical of Commissioner Landis as the personification of the racism that consigned such talented players as Satchel Paige and Josh Gibson to the separate and decidedly unequal world of black baseball. Given the relentless campaign for the integration of the national pastime, the silence of the black press on the alleged effort of Veeck to buy the Phillies in order to integrate the team — and the interference of Landis — is deafening.17

If Veeck was lining up money for his purchase, if Saperstein and Young were lining up players for the team, it is inconceivable that Veeck’s Phillies project would not have become a matter of public currency, at least within the world of Negro baseball. That the black press refrained from reacting with great vehemence to the betrayal of Veeck by the white authorities, especially in light of its campaign for the integration of baseball, is simply not believable.

The lone black writer to comment on the sale of the woebegone Philadelphia franchise was Joe Bostic of The People’s Voice, a self-described “militant paper” for “the New Negro,” and his report made no reference to Bill Veeck as a possible buyer of the club. An uncompromising and scathing critic of Landis and the moguls of white baseball, Bostic wrote that “the officials of the National League are the most relieved men in the world now that they have unloaded the phutile Phillies … Giving the Phillies to a group of businessmen will hardly solve the problem of making a ball team out of them. They should have been turned over to a group of magicians. …” Not a word about Veeck or his alleged plans.18

Nat Low, the white sports editor of the Communist Party’s Daily Worker, was the lone sportswriter to raise the issue of integration with regard to the sale of the Phillies, but the name of Bill Veeck is conspicuously absent from his column, too. Low issued a caustic “goodbye and good riddance” to Nugent for his “attitude toward Negro stars. For a comparatively small price he could have gotten the best stars in the game from the Negro leagues.” Low noted that the only place where Bill Cox, the new owner of the team, “can look for first rate players is among those Negro stars who have never been given a major league chance.”19

Is it possible that the black press either did not know in 1943 about Veeck’s plans or decided to avoid making a major issue of the ill-fated scenario so as not unduly to alienate the baseball establishment and thus compromise the ongoing effort to promote the signing of black players by one or more of the existing owners?

Perhaps, but it is very improbable. Those constraints, for example, certainly did not apply when Veeck, hard on the heels of Jackie Robinson’s signing with Brooklyn in October, 1945, succeeded in purchasing the Cleveland Indians on June 22, 1946, heading up a ten-man syndicate which put up a reputed $2 million for the club.

Cleveland events

Cleveland’s daily newspapers, the Plain Dealer, the Press, and the News, covered Veeck’s negotiations and his plans to improve the team’s fortunes in minute detail. Every aspect of club operations was subjected to analysis and speculation. There was fascination with Veeck himself, a brash 32-year-old ex-Marine with a history of building attendance with amusing and sometimes bizarre stunts. Veeck regaled reporters with his plans to revitalize the club, intending to buy at least three new players at the first opportunity and to undertake a major rebuilding job for 1947. During the weeks and months following his purchase, Bill talked incessantly to the press about every conceivable aspect of club operations — resumption of radio broadcasts, reorganization of the front office, increased ticket outlets, a final move from old League Park to mammoth Municipal Stadium. One thing he never mentioned was an earlier attempt to buy the Phillies, let alone the possibility of signing Negro Leaguers.20

Similarly, with one interesting exception, none of the leading dailies in other major league cities made any reference to a prior effort to buy the Phillies or even remotely hinted that Veeck might be interested in signing black players. The July 3, 1946, issue of The Sporting News contained extensive coverage of the sale of the Cleveland franchise along with several profiles of Veeck, all without reference to the Phillies or racial integration, a curious omission if, as Veeck says in his book, Ford Frick had bragged “all over the baseball world… about how he had stopped me from contaminating the league” back in 1943.21

The exception was the New York Herald Tribune, which printed a column by Red Smith in which the former Philadelphia Record writer commented: “Hardly anyone knows how close Veeck came to buying the Phillies when the National League was forcing Gerry Nugent to sell. He had the financial backing and an inside track, but at the last moment he decided the risk was too great to take with his friend’s money.” Smith, who had been in Philadelphia at the time of the Phillies’ sale, obviously knew of Veeck’s interest resulting in his meeting with Nugent in October `42. This was a matter of public record. The rest of the tale he evidently got from Sportshirt Bill, and it hardly matches the actual course of events as they occurred in the winter of 1942-43. Significantly, again, even Red Smith’s recollection never mentions any plans for racial integration of the Phillies, and it was Veeck himself, in Smith’s version, who ended his pursuit of the Philadelphia franchise, not Landis or Frick.22

While black newspapers elsewhere ignored Veeck’s purchase of the Indians, it was of special interest to Cleveland’s black newspaper, the Call and Post, which had long promoted the Negro Leagues generally and the local Buckeyes of the Negro American League specifically as a potential source of major league ballplayers. On July 20, 1946, the paper featured sports editor Cleveland Jackson’s interview with Veeck under a banner headline reading “INDIAN OWNER WOULD HIRE QUALIFIED NEGRO PLAYERS.” Stating that he had “absolutely no objections to playing Negro baseball players on the Cleveland Indians,” Veeck told Jackson that “in my opinion, none of the present crop of Negro players measure up to big league standards.”

Indeed, Veeck’s purchase of the Indians by itself argues against the existence of an earlier attempt to acquire the Phillies. Although Rickey had breached the color line in Organized Baseball by signing Jackie Robinson, who was performing well with the Montreal Royals in the International League during the summer of 1946, the racial integration of major league baseball itself remained uncertain. Given the widespread and adamant opposition to integration and the unhappiness within the game with Rickey’s course, why would the owners permit the sale of the Indians to Veeck if his intention to sign black players was known to them, as he claimed it was? Most of the men who had owned major league clubs in 1943 were still around in 1946. Contemporaneous accounts stressed that Veeck’s acquisition of the Indians was consummated precisely because of his long-standing close ties with powerful figures in the baseball establishment, including the late Judge Landis.23

Reaction to real integration

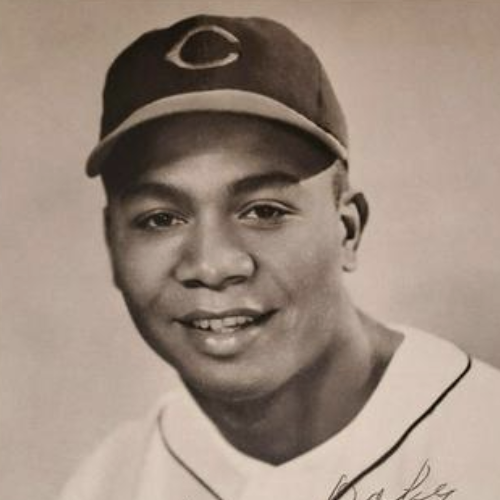

On July 3, 1947, Veeck’s Cleveland club purchased Larry Doby from the Newark Eagles, thereby making Doby the first black player in the American League. Veeck explained his acquisition by saying, “Robinson has proved to be a real big leaguer. So I wanted to get the best of the available Negro boys while the grabbing was good. Why wait? Within ten years Negro players will be in regular service with big league teams.”24

On July 3, 1947, Veeck’s Cleveland club purchased Larry Doby from the Newark Eagles, thereby making Doby the first black player in the American League. Veeck explained his acquisition by saying, “Robinson has proved to be a real big leaguer. So I wanted to get the best of the available Negro boys while the grabbing was good. Why wait? Within ten years Negro players will be in regular service with big league teams.”24

But in all the press comment that followed the historic signing of Doby — by Veeck, by other baseball figures, by white sportswriters, by black sportswriters — no one suggested that this action might have been foreseen from an earlier attempt by Veeck to buy the Phillies or to stock the team with blacks. And in praising Veeck for signing Doby, no one, including such ardent advocates of integration as Sam Lacy, Wendell Smith, and Fay Young, even hinted at an earlier attempt with the Phillies. Silence from Young and Smith is especially instructive, because Veeck at various later times named them as parties to his planned purchase of the Phillies. Telling, too, is the failure of Lou Boudreau, player-manager of the Indians during Veeck’s ownership, and Hank Greenberg, vice-president and second largest stockholder in the club, to mention in their books that racial integration of a big league team had been Veeck’s longtime if deferred goal. Then-commissioner Albert B. “Happy” Chandler candidly discussed in his memoirs the Negro Leagues and Landis’s opposition to racial mixing without reference to Bill Veeck. Finally, even Abe Saperstein never corroborated Veeck’s story.25

A year later Veeck signed the legendary Satchel Paige to an Indians contract. Long the best-known Negro League performer and the personification of black baseball, Paige was bitter that he had not been the first to breach the color line. How natural it would have been for Veeck to share the story of his aborted purchase of the Phillies, with Paige as one of his intended trailblazers, to assuage Satchel’s wounded pride. But no such reference ever appeared in either the black or white press after Paige’s signing, and there are no mentions of the story in either of the pitcher’s autobiographies, indicating that Veeck never told the story to Paige. The same is true of Orestes “Minnie” Minoso, who discussed his signing with Cleveland in the context of being among the first wave of blacks in the majors but did not mention any particular commitment to integration on the part of the Indians’ owner.26

Curiously, Veeck in his book says that he was “almost sure” when he bought the Indians that he would sign a black player but that he moved “slowly and carefully, perhaps even timidly” because he “wasn’t that sure about Cleveland.”27

An odd comment, indeed, for a man who was determined to sign black players in 1943, and to introduce them into Philadelphia, widely perceived as among the most racist northern cities, a city which suffered a crippling transit strike in 1944 over the issue of employing black trolley drivers. Besides, Cleveland was in the forefront of integrated sports, its football Browns having signed the African American stars Bill Willis and Marion Motley before Veeck bought the Indians. Although not cellar-dwellers, the Indians, who limped home to a sixth-place finish in 1946, were surely in need of an infusion of new talent. Yet Veeck made no attempt to sign Negro Leaguers en masse, signing only Doby in `47, followed by Paige and Al Smith in 1948, and Luke Easter, Minoso, and Harry “Suitcase” Simpson in 1949.28

Even after the “revelation” in Bill Veeck’s 1962 book, Doc Young, a sports journalist and historian of African Americans in sport, wrote an article in Ebony on the signing of Larry Doby back in 1947, in which Young mentions Veeck extensively but makes no reference whatever to any earlier attempt to integrate the Phillies. Young’s silence is significant because, as sports editor of Cleveland’s black newspaper during Veeck’s tenure with the Indians, Young said he “spent countless hours” with Satchel Paige after his signing. If Paige had any inkling of the aborted Phillies’ integration, he would surely have passed it on to Doc Young. Moreover, it is significant that no Negro League player has ever recorded having been contacted by Saperstein for Veeck’s Phillies.29

The Wendell Smith article

Pittsburgh Courier sports editor Wendell Smith appears to be the only major black sportswriter to mention Veeck’s autobiography. Smith recommended the book, noting that readers “will be exposed for the first time.. .to all the hypocrisy and chicanery” of “Frick and his ilk” when they learned that “Veeck contemplated buying the Philadelphia Phillies and signing Negro players.”30

Wendell Smith had written several months earlier about Veeck’s aborted purchase of the Philadelphia club in a series of articles on Abe Saperstein, the white founder and owner of the legendary all-black Harlem Globetrotters basketball team. He says that Veeck and Saperstein became “partners” in the scheme to purchase the Phillies and turn the club into an all-black team, that they offered Nugent some $250,000 for the franchise, but that because “baseball’s hierarchy” — specifically Landis and Frick-“would not tolerate Negro players in the majors,” Nugent sold the club to Cox for $85,000 in order to “keep the majors lily-white.”31

Smith’s report is of major significance inasmuch as it is the only known published account of the plan not taken from those written by Veeck himself. We quickly notice that the details of Smith’s story differ greatly from those set down at about the same time in Veeck-As In Wreck. Yet, although Veeck later identified Smith as one of his “confidants” in his plan to buy the Phillies, the account in the Courier is not based upon Smith’s first-hand knowledge but on an interview with Veeck in early March, 1962, at his home in Easton, Maryland. What becomes painfully clear from this interview, from the passage in Veeck’s book, and from several accounts Veeck gave later to others is that he had a singularly cavalier attitude toward the details of this story — or that he couldn’t remember from one time to the next how he had told the story.

Internal inconsistencies

The errors contained in Veeck’s autobiography are further evidence that the account is a latter-day construction. Doc Young, described as sports editor of the Chicago Defender, was not. The sports editor’s name was Fay Young. Veeck talks of the Phillies leaping from seventh place to the pennant in 1944, but the sale of Nugent’s club took place before the 1943 season. He mentions as among the black players “in action and available” both Monte Irvin, who was in the military service, and Luke Easter, who would not even begin his professional career until 1946. Beyond these errors, Veeck in subsequent years gave other versions of the story — to Donn Rogosin, to Jules Tygiel, and to Shirley Povich — that contradict what he said in his own book. In fact, when Jules Tygiel asked if Landis had in fact prevented him from buying the Phillies, Veeck replied, “I have no proof of that. I can only surmise.”32

Not only did Bill Veeck contradict himself in subsequent accounts, he even did so before his autobiography appeared. In the summer of 1960, he wrote an article about blacks in baseball for Ebony magazine. Toward the close of the article, he wrote:

Back in 1942, I suggested that the only reservoir of players still untouched during the war was the Negro leagues. As a matter of fact, I wanted to buy the Philadelphia ball club to put in an all-Negro team. It wasn’t really aimed at being an all-Negro team, but it would have worked out that way. I was going to add 15 Negro players who were better than anything that Philadelphia had and would have won the pennant by 30 games. I could have gotten Robinson, Paige, Don Newcombe, a pretty fair catcher named Roy Campanella, and we had the club put together. That plan was done away with.33

Veeck, in telling this story to a black sportswriter, never mentions any involvement of Abe Saperstein or any black writers in his plan, not even Doc Young, a frequent contributor to Ebony, or Fay Young of the Chicago Defender. There is no mention of any concrete offer to Nugent, the location of financing for a purchase, or any interference in a deal by Landis or Frick. Veeck probably came closer to the truth in this article than in anything he said later about the proposed Phillies deal: he did want to buy the club and he thought about getting black players for it. But nothing came of it after his one meeting with Gerry Nugent. “That plan was done away with,” he says, rather quaint phraseology that appears to mean, “Nothing more came of it. That was all.” Clearly, the story was embellished and changed for the autobiography a couple of years later.

External considerations

How about the Saperstein connection? Many of the players Veeck suggests Abe had lined up for him in `42-’43-Paige, Campanella, Easter, and Irvin in Veeck-As In Wreck; and Paige, Campanella, Robinson, and Newcombe in the Ebony article-were not available at the time, though they looked good from a 1960-62 perspective. Besides, had Abe Saperstein actually made arrangements with any Negro League players, nothing would have prevented Veeck from signing them to Milwaukee Brewer contracts when the rug was allegedly pulled from under him with the Phillies. Surely the solidity of the American Association, as a foothold in Organized Baseball just one step below the majors and with scheduling and financial stability far superior to anything the Negro Leagues could offer, would have appealed to Saperstein’s recruits, if they had really existed.

How about Veeck’s own nature? Can we really believe that Bill Veeck, baseball’s great iconoclast, would have suffered a betrayal and double-cross of the nature described in his book without saying a word to anyone? That thought boggles the mind. But no one, in Philadelphia, in Milwaukee, in Chicago, or anywhere else, heard a peep out of Veeck when the league bought the franchise from Nugent and then sold it to Cox.

How about Gerry Nugent’s economic realities? Can we really believe that Gerry Nugent, not a man of independent means, would have accepted without a murmur the league’s payment of half of what Veeck was establishing as the market value of the franchise — a value that he was, according to Veeck’s story, expecting to receive?

How about Veeck’s economic realities? It is not impossible that Veeck, who was accustomed to operating on a shoestring, could have gotten financing for such a purchase, but it is unlikely. A bankrupt baseball team seems an odd investment for the CIO to make during the war, when it was focusing on maintaining its peacetime gains and coping with the stresses of a wartime economy, and no evidence of such intention has been found. However, representatives of the CIO, at the major league meetings in December, 1942, did make a fruitless request that Landis conduct a hearing on integrating baseball; this may well have been what later got the CIO into Veeck’s story.34

How about the time frame? The timing of Veeck’s yarn is completely different from the November-to-February span that actually occurred. Veeck met with Nugent in October, after the World Series. But in December, at the major league meetings in Chicago, Nugent admitted that no bona-fide potential buyer could be found.

Why didn’t Ford Frick rebut the story? Some suggest that the failure of Frick, baseball commissioner in 1962 when Veeck’s book appeared, to react publicly to being charged with scuttling the purchase of the Phillies may at least be negative corroboration of Veeck’s story. It seems more likely, however, that since Sportshirt Bill took numerous potshots at Frick throughout his book the commissioner decided that his best course would be to ignore Veeck’s work altogether. The baseball press generally gave the volume short shrift, so there was little pressure on Frick to respond to any of Veeck’s charges. He probably ignored Veeck at the time because no one else seemed to give much credence to the Phillies-integration story, and he made no mention of it in his own autobiography.35 This was the tactic evidently pursued by other frequent targets in the book like George Weiss and Del Webb.36

There is one other curious feature pertaining to Veeck’s story, a feature which serves to invalidate the whole tale. As we have seen, Veeck says in his book that after the Phillies were sold elsewhere, “word reached me soon enough that Frick was bragging all over the baseball world-strictly off the record, of course — about how he had stopped me from contaminating the league.” If this were so, and his plans and their frustration were known to writers and executives “all over the baseball world,” the remarkable fact that not one of them ever revealed the secret meant that for the first time in history these individuals — not one of them but all of them — took an historically significant story to their graves. Everybody knew about it, but not one man of them ever came forward and said, “This is what old Bill Veeck tried to do back in nineteen and forty-two.”37

Why would Veeck manufacture the story?

Obviously something caused Veeck to include this story in his book twenty years after the fact. There are several possible reasons, though we will never know for sure.

* Early in 1942, Joe Bostic wrote a column entitled “Dreamin” in The People’s Voice. In his dream Bostic was a broker selling black ballplayers as replacements for major leaguers away in the military. After describing a couple of individual sales, he says, “I set up a deal to sell Jerry [sic] Nugent the entire Homestead Grays club as a unit to replace the Phils.”38 We do not know that Veeck was aware of Bostic’s column, but it was illustrative of the speculation commonplace at the time about the possible impact of Negro League talent on weak major league clubs-particularly a club like the Phillies.

Several months later, Satchel Paige mused in The Sporting News about what would happen if a squad of top Negro League players were entered in one of the major league races. No doubt Veeck did see this item, and it piqued his fertile imagination. He would put together such a team! Rudie Schaffer confirms that Veeck talked with Saperstein, a power in black baseball in the Midwest, about procuring players. He even had the idea of holding two separate spring training camps, one, as a blind, for the white players he was not going to use, the other for the blacks who would constitute his team when the season started.39

Several months later, Satchel Paige mused in The Sporting News about what would happen if a squad of top Negro League players were entered in one of the major league races. No doubt Veeck did see this item, and it piqued his fertile imagination. He would put together such a team! Rudie Schaffer confirms that Veeck talked with Saperstein, a power in black baseball in the Midwest, about procuring players. He even had the idea of holding two separate spring training camps, one, as a blind, for the white players he was not going to use, the other for the blacks who would constitute his team when the season started.39

When the opportunity to talk about purchasing the Phillies came up, Veeck jumped at it, only to have the idea dashed by Nugent’s insistence on “large figures.” Sportshirt Bill may have followed up with some efforts to secure financing, although no evidence of any has been found, but it is clear that nothing further transpired with Nugent, and Veeck went back to thinking up ways to jazz up attendance for his Milwaukee club.

There was no acceptance of an offer by Nugent and no interference in a Veeck-Nugent deal by Landis or Frick. The baseball executives might have acted in the way described by Veeck, had the situation come up, but it is manifestly unfair to convict them of something they never had a chance to do. Veeck, nothing if not a storyteller, seems to have added these embellishments, putting black hats on the commissioner and league president, simply to juice up his tale. Because of Landis’s well-known aversion to integrated baseball, Veeck’s tale found believers, which was unfair to Frick, who, flawed though he may have been, was not in the judge’s class in his attitude toward black players.40

* Clearly, by 1962, Bill Veeck had wearied of hearing about Branch Rickey as the breaker of baseball’s color bar, when Veeck himself had had it in his heart and mind to shatter that bar four or five years earlier. It is obvious from Veeck’s book that he was no great admirer of Rickey, and we may be sure it galled him that the Brooklyn president got the credit for baseball’s integration — a step, Veeck felt, that Rickey took only for business reasons. Moreover, Veeck always took pride in the fact that he behaved honorably in purchasing Doby’s contract from the Newark Eagles, in contrast to Rickey, who refused to compensate the Kansas City Monarchs for Robinson. In order to make what he had wanted to do more plausible, Veeck added the fictitious details which made it seem that only the nefarious, racist actions of baseball’s leaders kept him from his crusading role, not something as mundane as his own inability to raise enough money.

* Another possible reason for the creation of the story of his frustrated attempt to buy the Phillies was Veeck’s belated consciousness that he could have integrated the Milwaukee Brewers in the American Association but made no effort to do so. If Bill Veeck had signed prominent black stars to his minor league club, Judge Landis, who had in any event no administrative authority over the minor leagues, could no more have forbidden such signings as “detrimental to baseball” in the midst of World War II than he could have if Veeck had signed them to major-league contracts. (“With Negroes fighting in the war,” Veeck wrote, “such a ruling was unthinkable.”)

After his black signees made good at the Triple-A level, Veeck could presumably have sold them to major league clubs for big dollars, a course of action always dear to his hustler’s heart. There is no evidence that he considered signing black ballplayers for the Brewers, another sign that the crusading zeal recalled in 1962 may have been ex post facto.41

* Finally, this story may have resulted from Bill Veeck’s ill health at the time he sat down with Ed Linn to do his book. Seriously ill, Veeck sold the White Sox in 1961 on doctors’ orders. When he went to Easton, he probably felt that this book was to be his last chance to poke the baseball powers in the eye, to steal some credit from Rickey, and to polish up his own place in baseball history. The Phillies’ story, with its exaggeration and embellishment, was not the only tall tale in the book, but it was the one that became Historical Truth.

The question remains, of course, as to why Veeck’s story has been accepted so unquestioningly, without even the most rudimentary research to see if it checked out. It is especially surprising that academic historians failed either to verify Veeck’s claim or to investigate more fully a story of major significance for both baseball and social history, although in many instances, to be fair, the Veeck story was peripheral to the events being written about. Still, no one ever looked into it. Perhaps the canons of professional research were set aside in this instance because Veeck and his yarn fit in nicely with personal preconceptions and values. Kenesaw Mountain Landis has been held up as the principal villain (along with Cap Anson, who was no longer around) in the long-successful conspiracy to keep Organized Baseball lily-white.

Veeck, on the other hand, has been a favorite of historians as the irreverent, unconventional antithesis of the stuffy and bigoted rulers of baseball. Given the cast of characters — Landis, the crusty and biased keeper of the bar against blacks, and Veeck, the iconoclastic employer of midgets, demolisher of disco records, creator of exploding scoreboards, and spokesman for “the little guy” — and the cause — racial justice in the national pastime — it is hardly surprising that historians still wanted Veeck’s tale to be true. Bill Veeck is a more appealing crusader than the sanctimonious Branch Rickey, and his story has the added fillip of letting us believe that his plan was thwarted by the guardians of privilege and racism.

Nonetheless, we must face the fact that Bill Veeck falsified the historical record. This is unfortunate. His actual role in advancing the integration of major league baseball is admirable and can stand on its own merit.

Notes

1 See, for example, Bruce Kuklick, To Every Thing A Season: Shibe Park and Urban Philadelphia (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1991), 146; Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and his Legacy (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 40-41; Geoffrey Ward, Baseball: An Illustrated History (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1994), 283; G. Edward White, Creating the National Pastime: Baseball Transforms Itself 1903-1953 (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1996), 147; Benjamin G. Ruder, Baseball: A History of America’s Game (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1992), 150; Charles C. Alexander, Our Game: An American Baseball History (New York: Henry Holt, 1991), 194; David Q. Voigt, American Baseball, v. II, From the Commissioners to Continental Expansion (Norman: U. of Oklahoma Press, 1970). 297, and America Through Baseball (Chicago: Nelson-Hall, 1976), 116; Harvey Frommer, Rickey and Robinson: The Men Who Broke Baseball’s Color Barrier (New York: Macmillan, 1982), 98; Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues, 1884-1955 (New York: Birch Lane Press, 1995), 265; Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The HilIdale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-32 (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 1994), 18; Jim Overmyer, Effa Manley and the Newark Eagles (Metuchen, N.J.: Scarecrow Press, 1993), 236-237; Janet Bruce, The Kansas City Monarchs: Champions of Baseball (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1985), 109; Donn Rogosin, Invisible Men: Life in Baseball’s Negro Leagues (New York: Atheneum, 1983), 196-97; Robert W. Peterson, Only the Ball Was White (Englewood Cliffs, NJ.: Prentice-Hall, 1970), 180; Joseph Thomas Moore, Pride Against Prejudice: The Biography of Larry Doby (Westport, CL: Greenwood Press, 1988), 39; Arthur Ashe, A Hard Road to Glory: A History of the African American Athlete Since 1946 (New York: Warner Books, 1988) v. 3, 9; and Mark Ribowsky, Don’t Look Back: Satchel Paige in the Shadows of Baseball (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1994), 245.

2 Gerald Eskanazi, Bill Veeck: A Baseball Legend (New York, McGraw-Hill, 1988), 25-26. According to Eskanazi, Veeck tried to buy the Phillies in 1945, apparently after the season (the author cites the statistics of the `45 Phils to show what Veeck proposed to correct with his influx of black players), but was frustrated by judge Landis, who had of course passed away in November, 1944.

3 Richard Orodenker, ed. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1996), 53-55.

4 Los Angeles Times (undated clipping, Natl. Baseball Library). Murray even has Veeck showing Landis his roster of proposed Phillies, “a1l signed and collected by Saperstein, Veeck and a Chicago newsman named ‘Doc’ Young.” Murray’s version of the 1942 Phils (which of course missed the actual time of the sale by a year) included, along with Paige, Campanella, and Irvin, such additional Negro League luminaries as Cool Papa Bell, Theolic Smith, Buck Leonard, and Josh Gibson. Murray’s column is replete with factual errors, which tend to lessen the reader’s confidence in his conclusions.

5 Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 8, 1943.

6 Tommy Hughes, a promising young pitcher, was drafted into the army, so Nugent could not have sold him even if permitted to do so. Over the course of the ten years in which he ran the Phillies, Nugent traded or sold such players as Pinky Whitney, Spud Davis, Chuck Klein, Don Hurst, Dick Bartell, Kiddo Davis, A] Todd, Ethan Allen, Curt Davis, Dolph Camilli, Bucky Walters, Claude Passeau, Max Butcher, Morrie Arnovich, and Kirby Higbe. A shrewd judge of talent, Nugent often picked up valuable but unsung players in return, many of whom he then sold for more cash.

7 Philadelphia Record, Nov. 12, 1942.

8 Philadelphia Inquirer, Dec. 3, 1942.

9 Philadelphia Inquirer, Feb. 1, 1943.

10 Philadelphia Record and Evening Bulletin, both Feb. 10, 1943. The new owner, Cox, meddled constantly in baseball affairs he knew nothing about, attracted more media attention than his team did, fired manager Bucky Harris because he wouldn’t talk baseball with him at all hours, thereby stirring up a players’ revolt, and was thrown out of baseball after the `43 season for betting on his team’s games.

11 Bill Veeck, with Ed Lion, Veeck-As In Wreck (New York: G.E Putnam’s Sons, 1962), 171-172.

12 Daniel Cattau wrote an article in the April 1991 Chicago Reporter, “Baseball Strikes Out With Black Fans,” in which he recites the story of Landis frustrating Veeck’s plan to buy the Phillies, based on the recollection of Veeck’s widow, Mary Frances. That sounds authoritative, until one recalls that Bill and Mary Frances did not meet until the fall of 1949 and were not married until April 29, 1950. So, whatever knowledge Mary Frances had of the aborted purchase of the Phillies traced back to the same source as all the other stories: Sportshirt Bill and his tales.

13 Milwaukee Journal, Oct. 18, 1942; phone interviews with Rudie Schaffer, Aug. 24, 1994, and Gerald P. Nugent, Jr., May 21, 1994. “You have to remember Veeck was a showman,” Nugent’s son said.

14 The Sporting News, Nov. 19, 1942.

15 The following African American newspapers were researched for all aspects of this paper: the Philadelphia Tribune, Pittsburgh Courier, Baltimore Afro American, Chicago Defender, the Cleveland Call and Post, Kansas City Call, the Amsterdam News (New York), the New York Age, The People’s Voice (New York), the New Jersey Afro American (Newark), the Philadelphia Afro American, the St. Louis Argus, Los Angeles Sentinel ,and the Washington Afro American.

16 Philadelphia Inquirer, Nov. 12, 1942. Careful review of the Philadelphia and Milwaukee papers for the time from that date to February 20, 1943, shows no further references to Bill Veeck as a possible buyer of the Phillies, although many other names were mentioned.

17 See Tygiel, op. cit., 30-4 1, and David K. Wiggins, “Wendell Smith, the Pittsburgh Courier-Journal and the Campaign to Include Blacks in Organized Baseball, 1933-1945,” Journal of Sports History, 10 (Summer 1983), 5-29.

18 The People’s Voice, Feb. 27, 1943.

19 Daily Worker, Feb. 11 and 26, 1943.

20 Cleveland Plain Dealer, Cleveland Press, the Cleveland News, and the Cleveland Call and Post, the city’s black newspaper, from June to December 1946.

21 Emphasis added; Veeck and Linn, op. cit., 172.

22 New York Herald Tribune, June 25, 1946. Curiously, too, “his friend’s money” hardly sounds like backing from the CIO.

23 See, for example, the Cleveland Plain Dealer, June 23, 1946, and The Sporting News, July 3, 1946. As an instance of the owners’ displeasure with Rickey, see Red Smith’s story, quoted in Ira Berkow, Red: A Biography of Red Smith (New York: Times Books, 1986), 109, of an interview with Connie Mack, the “Grand Old Man of Baseball,” during the 1946 spring training. When asked what would happen if the Dodgers brought Robinson to a scheduled exhibition game with the Athletics, “Mack, recalled Smith, ‘just blew his stack. “I have no respect for Rickey,” Connie said. “I have no respect for him now.” He went into a tirade.’”

24 Cleveland Plain Dealer, July 4, 1947.

25 Baltimore Afro American, July 5, 12, 19, 1947; Chicago Defender, July 12, 19, 1947. See also the Kansas City Call, July 11, 1947; New Jersey Afro American (Newark), July 12, 1947; New York Age, July 12, 1947; Amsterdam News (New York), July 12, 19, 1947; Philadelphia Afro American, July 12, 1947; Pittsburgh Courier, July 12, 1947; and Washington Afro American, July 7, 1947. Lou Boudreau with Ed Fitzgerald, Player-Manager (Boston: Little, Brown, 1949), 77-81, 105-08, 161-64; Lou Boudreau with Russell Schneider, Lou Bondreau: Covering All the Bases (Champaign, Ill.: Sagamore Publishing, 1993), 11-14, 95-98, 143ff; Hank Greenberg, Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life (New York: Times Books, 1989), 198-207, 216-17, 248-49; Albert B. Chandler with Vance Trimble, Heroes, Plain Folks, and Skunks: The Life and Times of Happy Chandler (Chicago: Basic Books, 1989), 224-29; Dave Zinkoff with Edgar Williams, Go, Man, Go (New York: Pyramid Communications, 1971), 46. Saperstein wrote the foreword to this “official” history of the Harlem Globetrotters, originally published in 1953 as Around the World With the Harlem Globetrotters.

26 Leroy (Satchel) Paige, as told to Hal Lebovitz, Pitchin’ Man (Cleveland: n.p., 1948); Leroy (Satchel) Paige, as told to David Lipman, Maybe I’ll Pitch Forever (New York: Doubleday, 1962); Minnie Minoso with Herb Fagen, Jest Call Me Minnie: My Six Decades in Baseball (Champaign, Ill.: Sagamore Publishing, 1994), 32-46.

27 Veeck and Linn, op. cit., 175.

28 Obviously, the number of blacks who were signed by Veeck was higher than that for most other clubs. Yet while he owned the St. Louis Browns, who certainly needed whatever help they could get, talent-wise, Veeck acquired no Negro Leaguers at all (except, of course, Paige again).

29 A.S. Young, “A Black Man in the Wigwam,” Ebony, February 1969. Also, Young’s column of May 10, 1962, in the Los Angeles Sentinel.

30 Pittsburgh Courier, July 21, 1962.

31 Pittsburgh Courier, March 14, 31, 1962. The $85,000 purchase price for Cox is clearly wrong, of course, an example of Veeck’s careless attitude toward the “facts” of his story.

32 Tygiel, op. cit., 41. Veeck told Rogosin that he hatched the plan “with only three confidants,” Rudie Schaffer, Wendell Smith, and Saperstein, that he told Landis of his plan in Chicago on his way home from wrapping up the deal with Nugent, and that “when he arrived home the next morning he discovered that the Phillies had been sold to the National League overnight.”

Rogosin, op. cit., 196-97. Finally, Veeck told Povich, the veteran sportswriter for the Washington Post that he had gone to Landis with his plan after the National League had taken over the team, that Landis referred him to Frick, and that Frick “wouldn’t talk business with us. Instead, he sold the Phillies to William Cox….” Bill Gilbert, They Also Served: Baseball and the Home Front 1941-1945 (New York: Crown, 1992), 220-22.

33 Bill Veeck, as told to Louie Robinson, “Are There Too Many Negroes in Baseball?” Ebony, August, 1960. Neither Robinson nor Newcombe (16 at the time) had started a professional career in 1942.

34 A check of the CIO archives at Wayne State University reveals no mention of Bill Veeck of the possible financing of his purchase of the Phillies.

35 Ford C. Frick, Games, Asterisks, and People: Memoirs of a Lucky Fan (New York: Crown, 1973). In describing his own support of Jackie Robinson, Frick mentions earlier attempts at integration and the opposition of Landis without a line shout Veeck’s alleged attempt in 1942-43; ibid., 93- 102. Of course, Ford Frick’s failure to put in a good word for Bill Veeck is hardly startling. The reviews of Veeck’s book do not mention the story of his attempted purchase and integration of the Phillies. See reviews in Time, July 27, 1962; Newsweek, July 30, 1962; Chicago Daily News, July 2, 1962; Chicago Sun-Times, July 2, 1962; Chicago Tribune, June 30, 1962; Los Angeles Times, July 24, 1962; New York Herald-Tribune, July 15, 1962. Alfred Wright of Sports Illustrated, reviewing Veeck’s book in the New York Times, said that reading it “is much like sitting with Veeck. . .through a few long nights in a saloon.” New York Times (Book Review), July29, 1962. The book was ignored by the two major Philadelphia papers, the Inquirer and the Evening Bulletin.

36 When portions of Veeck’s book appeared in Look magazine in early 1962, Webb responded with good-natured quips to Veeck’s charges against him; Philadelphia Inquirer, June 8, 1962.

37 Veeck and Linn, op.cit., 172.

38 The People’s Voice, March 12, 1942.

39 The Sporting News, August 13, 1942; old Satchel pointed out that there was no way such a team could afford him! Interview with Schaffer for Veeck’s plans. One wonders how eager Veeck’s backers would have been to finance two training camps instead of the usual one!

40 David Pietrusza, studying the life of Judge Landis, came across a letter which Veeck wrote to the commissioner from the South Pacific on May 22, 1944. Friendly in tone, the letter talks of Veeck’s Marine Corps experiences, which he says are “somewhat different from the last time I saw you, and, I can’t say nearly as interesting or enjoyable.” This hardly sounds like the writing of a man who was double-crossed as described in Veeck-As In Wreck.

41 Veeck and Linn, op. cit., 171.There is a strange statement in an essay Roger Kahn wrote on Jackie Robinson in The Baseball Hall of Fame 50th Anniversary Book (New York: Prentice-Hall, 1988), 215: “Once Bill Veeck told me that he tried to sign a few blacks for the minor league franchise he ran in Milwaukee and was told by Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis to go no further. It he went ahead, Landis said Veeck himself would be barred from baseball.” Obviously, Sportshirt Bill was getting his stories crossed by this time, but it is still incredible that a reporter like Kahn would simply accept such a statement without digging a little deeper, like asking, “On what authority, Bill?” In the same book, incidentally, on p. 204, appears a paragraph about Veeck’s frustrated attempt to buy the Phillies.