A Home Run by Any Measure: The Baseball Players’ Pension Plan

This article was published in the SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 21 (1992).

As your father shaved each morning with a Gillette safety razor and you watched the World Series in black & white on NBC-TV back in the 1950s, you probably never thought you were making it all possible for your favorite player to collect a pension check when he retired from baseball. But you were!

The Major League Baseball Players Benefit Plan might appear to be a less lively topic than the $23.5 million contract for Jose Canseco’s services with the Oakland A’s (and now the Texas Rangers). However, the inter-twining of TV revenue with baseball operations was pioneered through the development of the players pension plan. To a large degree the genealogy of escalating TV revenue to make possible Canseco’s multi-million dollar contract begins with the establishment of the pension plan back in 1946.

The seemingly dull and boring pension plan has helped to shape this phenomenon and other events which have changed the face of baseball history. Without the pension plan we also wouldn’t have witnessed the ill-fated experiment of two All-Star Games each year from 1959-62. In addition, pension plan negotiations had a direct relationship to the players’ 1969 boycott of spring training and 1972 season-opening strike, with a minor role in the 1985 in-season strike.

Negotiations in 1972 regarding the pension plan actually had an impact on who won the American League Eastern Division title. Stalled talks cased the first wide spread work stoppage during a baseball season, as the spring training strike drifted into the regular season. As a result, the Boston Red Sox lost the American League East title by half a game to the Detroit Tigers, even though both teams had the same number of losses.

Red Sox shortstop Luis Aparicio has been labeled the “goat” of this Boston shortcoming, for his two stumbles rounding third base in the crucial final series with the Tigers. However, the real “goat” was the owners’ decision to cancel enough games once the pension negotiations were concluded so that the Red Sox wound up playing one less game than the Tigers!

THE CURRENT PLAN

Today, it is an understatement to say that the Major League Players Association has been very successful in its collective bargaining endeavors for pension benefits with the owners of the major league baseball teams. The pension plan has an extremely generous benefit formula by pension industry standards, providing the maximum benefit permissible under federal law of $90,000 per year (or 100 percent of the last season’s pay, if less) to a member with ten or more years of major league service. This sum is payable to the player for his lifetime, and there are various contingencies for continuation of benefits to spouse and beneficiary after death.

Unlike most corporate pension programs, which typically gear pension levels to a member’s pay, baseball’s plan is based strictly on service. If you’ve got ten years of service, you get the maximum whether you’re a superstar, a utility infielder or a bullpen coach. This averages out to an expected pension of$7500 per month for today’s ten year player still in the game.

Like all baseball facts and statistics, the$90,000 maximum pension does need to be put into perspective. For a player to receive this sum at retirement, he must have had active service during or after the 1970 season, have had ten years of playing time, and wait to draw his pension at age 62. Also, the salary in his highest three consecutive years of service must have averaged $90,000 a year.

While attainable for the current player, the $90,000 maximum benefit has been received by few players to date. The average pension payment in 1987 was just $13,593. Many players begin receiving their pension be fore age 62, and many left the majors before 1970, when benefit levels were lower than today’s program.

Regular payment begins under the plan at age 62, but payments can be received as early as age 45 at a reduced level to account for the longer period that benefits will be received. A member with ten years of service would still get about$35,000 annually at age 50 or about $2875 per month. Vesting is extremely rapid, as a player with as little as forty-four days of major league service can now qualify for a pension payment.

To fund these benefit levels, the owners contribute substantial sums each year. The settlement of the 1990 spring training lockout involved an increase in the owners’ annual pension contribution from$39 million to$55 million. These sums are tax-deductible by the owners as long as the pension plan continues to conform to a complex set of federal pension laws and regulations.

As with many labor-management negotiations, though, it wasn’t always this way.

A pension plan for any group of professional athletes has its own special challenges. Athletes today are highly paid, creating a need for deferred compensation pro grams with high benefit levels. But the working career of an athlete is usually quite short, compared to other occupations, creating a need for shorter vesting schedules and earlier distribution dates. This contribution forces a shorter funding period than would be typical for a normal corporate pension plan, creating higher costs for the plan sponsor.

Baseball players create an even bigger administration challenge-keeping track of major league service. As anyone who follows the New York Yankees’ exploits with its Columbus, Ohio minor league team can appreciate, keeping track of major league service can be a major league headache!

Baseball lives by the Law of the Survival of the Fittest. As a player’s physical skills deteriorate in his later playing days, younger players will replace him. There is no implied contract of perpetual employment. However, with no preparation for another career, players often drifted from one job to another or tried to make money off their former stardom, a situation that many found hard to cope with.

THE BEGINNINGS OF THE PLAN

Baseball’s pension plan was established in 1946 to take effect on April 1, 1947. Business Week magazine heralded the new program by writing, “Tear-jerkers in the Sunday supplements about once-great baseball players going to the poorhouse will be scarcer and scarcer from now on. Hereafter, there will be pensions for the tired wheelhorses that the big leagues turn out to pasture.”

There may have been a twinge of sentiment to take care of aging players, but the real reason the owners agreed to establish a formal pension plan was to avoid a players union, a topic then being trumpeted by Robert Francis Murphy as he attempted to make his American Baseball Guild a success.

A “special joint committee” was established in July 1946 to discuss the first changes in the player contract in several decades. Larry MacPhail, president of the Yankees, was the key participant on the committee, along with team owners Phil Wrigley of the Cubs, Tom Yawkey of the Red Sox and Sam Breadon of the Cardinals. Player representatives were also chosen by the committee to meet with it.

Johnny Murphy was the American League spokesman and Dixie Walker represented the National League, while the committee also asked Marty Marion to join the pension discussions. The choice of Murphy and Walker could be construed as meeting the committee’s needs. Both players were ten year veterans nearing the end of their careers who might be expected to “go along” with the owners to obtain a pension.

In August 1946 the committee issued its report to the Commissioner of Baseball Happy Chandler. The report’s recommendations included establishing the pension plan, as well as the first minimum annual salary of$5000 and the first spring training expenses of$25 per week. This seemed to quell player discontent and Murphy vanished as a baseball labor organizer. As noted, though, in Tony Lupien and Lee Lowenfish’s book The Imperfect Diamond, “because the pension was established by the owners as a sop to forestall player unionization, it would regularly become an area of great controversy every five years when it came up for renewal.”

The pension plan was established on a five-year trial basis and was funded initially with insurance contracts through The Equitable Life Assurance Society. While no longer the sole source of funding for the plan, now over $475 million in size, Equitable in the 1980s sponsored a series of Old Timer Baseball Games, using the marketing strength of its initial association with the plan. Equitable’s sponsorship was dropped in 1990 to save the financially troubled insurer a $5 million annual expense.

Initially, the benefit formula was set at $10 per month per year of service, payable at age 50. Five years minimum service was required to be eligible for a pension, and — as now — a maximum of ten years was to be taken into account for calculating the pension amount. A ten year player therefore would receive $100 per month at age 50, in stark contrast to today’s $2875 monthly level for a similarly situated player.

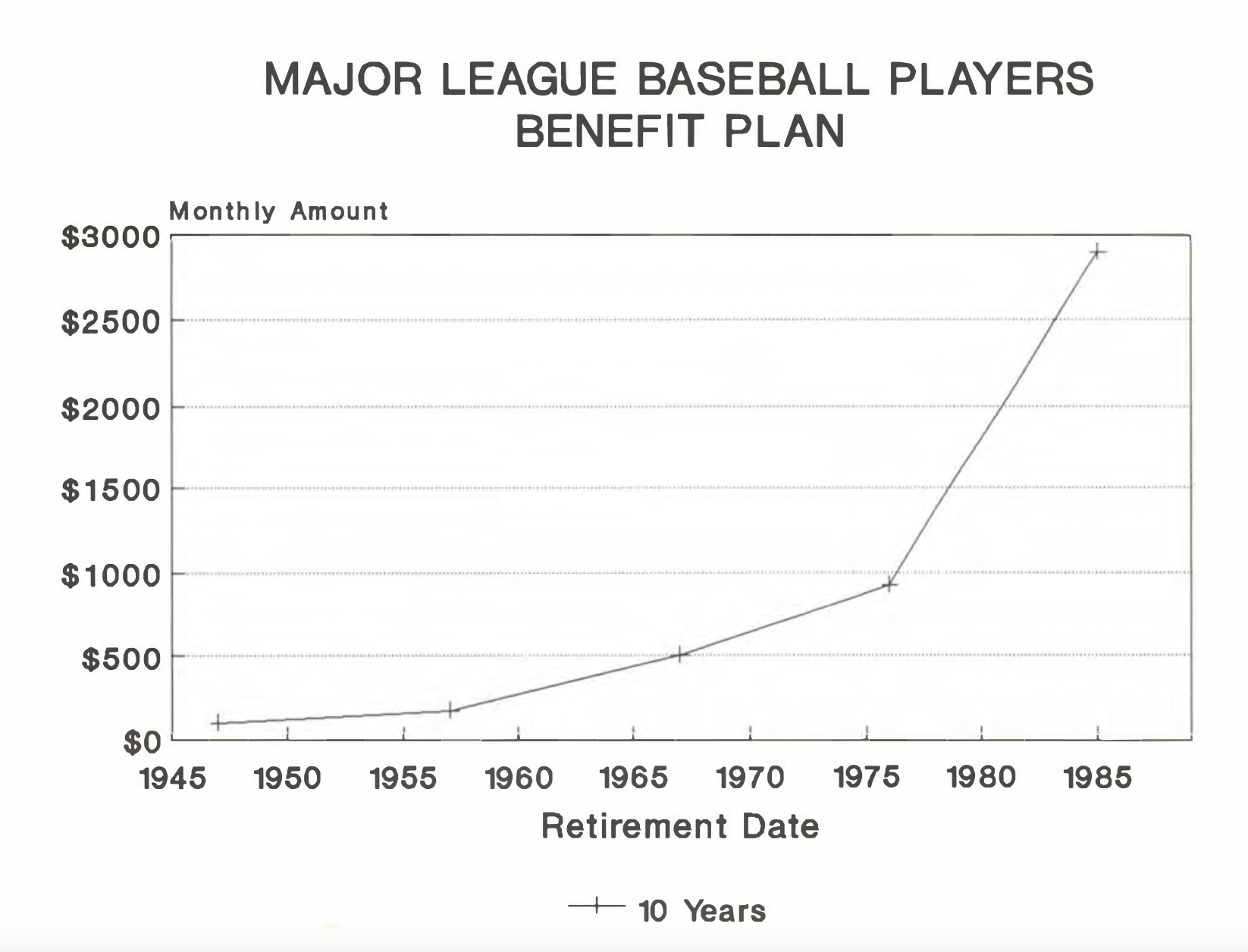

The graph on the final page of this article illustrates the dramatic increase in pension benefit levels since the plan’s inception in 1947.

As a “defined benefit” plan under the law, funds are set aside on an unallocated basis and used to provide the promised benefit levels to the plan members. This is in contrast to a “defined contribution” plan where funds are set aside according to some formula and segregated in individual member accounts, but without any promise as to level of monthly benefit that might be obtainable from that account.

WHERE THE MONEY CAME FROM

Players were required to contribute $250 per year to be included in the plan. Each team matched its players’ contributions, but in an unusual move by pension industry standards, the employers did not provide the majority of the additional funding required to support the benefit levels in the plan-customers and vendors would directly contribute to the players’ pension fund.

Proceeds from the annual All-Star Game and receipts from the sale of broadcast rights for the World Series also were designated to go towards the pension plan. This is akin to having factory tours and suppliers fund employee pensions rather than the employer. Initial funding for the plan was estimated to be $675,000, including a three year deal for the pension plan that Commissioner Chandler negotiated which paid $150,000 for World Series radio rights.

Actually, the idea of using gate receipts from the All Star Game to go towards player needs was not exactly new in 1947. W hen the All-Star Game was first conceived back in 1933 by Chicago Tribune sports editor Arch Ward, it was primarily as an attraction for the Chi cago World’s Fair. However, the game’s net proceeds of $46,000 — including $5,000 in radio rights paid by CBS — went to the Association of Baseball Players of America to help indigent players who had found them selves without resources in those trying days of the Great Depression. The ABPA was a purely charitable group, though, collecting dues for use in emergencies for former players who were aged or needy.

Using the sale of broadcasting rights to the World Series to fund the pension plan was an easy way out for the owners, as the money didn’t come directly out of their pockets. However, the owners failed to anticipate the impact that the media would have on baseball in the future, and the vast amount of revenue it would represent.

ELIGIBILITY PROBLEMS

To be eligible for the original plan, you had to be a player or coach on a major league roster as of April 1, 1947 (managers weren’t included until later). This cutoff date created a number of inequities for those long-service ballplayers lucky enough to procure a roster position.

One example of such a beneficiary was reported by The Sporting News to be Joe Judge, who had played from 1915 to 1934 but returned from private business to be a coach for the Washington Senators for 16 months in 1945 and 1946. This got him on the April 1, 1947 roster even though he didn’t coach in 1947. Judge was therefore eligible for a pension and following the pension improvements negotiated in 1957 began collecting $510 per month at age 63 until he died in March 1963.

In his autobiography Hank Greenberg: The Story of My Life, Greenberg recounted a story of another such beneficiary, 36-year-old catcher Billy Sullivan. Greenberg says he advised Sullivan that for $250 he could cash in on the pension plan. When Sullivan told Greenberg that he didn’t think any team would want him at that stage of his career, star Greenberg persuaded the Pirates, who had just acquired him from the Tigers, to sign Sullivan as a third string catcher for the 1947 season. Appearing in 38 games, 25 as a pinch hitter, Sullivan batted .255 for the last place Pirates backing up Dixie Howell and Clyde Kluttz at catcher. More importantly, he was afforded the opportunity to apply his previous 11 years of major league service going back to 1931 towards a pension.

Many other veteran players during the playing days of Sullivan and Judge, such as Babe Ruth, weren’t eligible for a pension because they weren’t in the right spot when the plan was instituted.

In 1950, Commissioner Chandler sold the TV-radio rights for the World Series and All-Star Game to the Gillette Safety Razor Company for $1,000,000 per year over the next five years to increase funding in the pension plan. This was partly in response to the need to fund the benefit for the widow of ten-year veteran Ernie Bonham, who had died at age 36. It turned out there wasn’t yet enough money in the program to fund this benefit!

“GOOD FAITH”

Growth of pension plans was spurred by the 1949 Supreme Court decision in Inland Steel vs. National Labor Relations Board which mandated that employers bargain in good faith with unions over pension benefits. With baseball owners having established the pension plan prior to the Supreme Court decision and putting in other compensation reforms, the players had no pressing need to establish a union to help them. They were negotiating with team owners on the pension issues without the benefit of a formal bargaining agent. They had only the assistance of the Baseball Commissioner.

As a result, the players were repeatedly rebuffed by the owners when they inquired about the pension plan, if only to get a simple accounting of the fund.

WHOSE MONEY IS THIS ANYWAY?

Fr ed Hutchinson and Marty Marion appeared at an owners meeting during the 1950 World Series to make some inquiries about the pension plan. They met with no success. Contributing to the players’ predicament was the 1951 resignation (or firing) of Commissioner Chandler, who was known to be sympathetic to the players’ interest in maintaining a good pension. (Chandler’s negotiating skills apparently could have used some strengthening, though, as Gillette reportedly turned around and cut deals with the Mutual Broadcasting System and BC for the TV and radio broadcasts to gamer it a profit on the $1 million it had paid Chandler.)

Allie Reynolds and Ralph Kiner, who succeeded Murphy and Walker as league reps, appealed again to the owners at a meeting at the 1953 All-Star Game for an accounting of the pension fund. Again to no avail. The players then decided to get some professional assistance, and hired J. Norman Lewis to serve as a liaison between players and owners. There was only one problem with this tactic — the owners refused to talk to Lewis!

In November 1953 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Toolson vs. New York Yankees to uphold baseball’s 1922 anti-trust exemption as a legal monopoly, successful bargaining with the owners was no longer assured. A continuing troublesome relationship over the pension plan was probably also guaranteed.

With its monopoly reaffirmed, the owners dug in. Lewis did get in to a December 1953 owners meeting in Atlanta, but reported the owners’ response on the pension accounting issue as “what business is it of the players? It’s not their money.”

This was in fact a true statement — it wasn’t the players’ money. At the time, there was a misunderstanding among the players that there was actually a “pension fund” that the contributions went to. It’s a requirement today that there be a trust to hold the pension money, but there was no such requirement then. The pension money was in reality part of the Commissioner’s “central fund” which paid for expenses of the office among other things as well as pension costs.

Ford Frick, who succeeded Chandler as Commissioner, finally broached the issue publicly in 1954. “It’s not a pension fund,” the New York Times reported Frick saying. “In 1951 it was agreed to continue the pension plan for a second five-year period … upon the definite under standing that all proceeds from radio and television and gate receipts would belong to the clubs and be paid into the central fund.”

To forestall further player inquiries, the Commissioner sent a booklet to each player explaining the plan provisions and the status of the plan’s funding. A true pension fund would shortly be established.

THE PLAYERS ORGANIZE

Not surprisingly, the Major League Baseball Players Association was then formed in 1954 to represent the players. Bob Feller was chosen as its first president.

Facing a $2.3 million past-service cost in 1954 (the cost to fund pre-1947 service) the owners threatened to terminate the pension plan in an attempt to gain some leverage in negotiations with the newly-formed players’ union. A new owners’ pension committee was formed in 1954 with John Galbreath, owner of the Pirates, and Greenberg, now general manager of the Indians.

Lewis was able to negotiate a compromise to have 60 percent of the national radio-TV revenue from both the World Series and All-Star Game go towards the pension plan with the past-service costs being paid by the end of 1955. A five-year contract was negotiated in 1956 for $3.25 million annually for these telecommunications rights.

With this increased funding, the benefit formula was increased in 1957 so that a five-year player would receive $88 per month at age 50 (up from $50) and a ten-year player $175 per month (up from $100). Additional credits were provided for ten to twenty years of service such that a twenty-year player would receive $275 per month at age 50. Changes were retroactive for all past service under the plan.

To illustrate the pension increase, The Sporting News used catcher Rollie Hemsley as an example of the windfall that some former players enjoyed. Hemsley played 1,593 games over 19 seasons in the majors with seven teams, including two games in 1947 with the Phillies, which qualified him for the pension plan. Under the former formula, Hemsley would get$100 a month at age 50, which would be that coming June. With the improved formula, he’d now get $265 a month. Those two games in 1947 really paid off!

THE EXTRA ALL-STAR GAMES

In 1959 rather than tinker with the 60 percent figure, it was decided that a second All-Star Game would be added that year to generate additional revenue for the pension fund.

A second All-Star Game was approved in early May of 1959 and was hastily arranged to take place in Los Angeles in August, following the already scheduled July exhibition at Forbes Field in Pittsburgh. The 1959 All Star contest in Los Angeles was the only such non-July game until the strike-rescheduled 1981 game.

In 1960 the games were played two days apart in the traditional early July time slot, as players played first in Kansas City and then trekked east to Yankee Stadium for the second game. This proved unpopular with the players, so in 1961 the two games were scheduled three weeks apart, in early and late July.

The games started to appear snakebit, as high winds at San Francisco’s Candlestick Park in 196 L blew Stu Miller off the mound. Then the only tie in All-Star history occurred when rain canceled 1961’s second game at Boston’s Fenway Park after nine innings with the score knotted 1-1. The All-Star Game has never returned to Boston in the 30 years since.

After a fourth year of two-a-season All-Star Games the concept proved unpopular with the fans as the second contest served to dilute the impact and exclusivity of the mid-season classic. By mutual consent, the second game was shelved after the 1962 season, with the owners agreeing to devote to the pension fund 95 percent instead of 60 percent of the gate and TV revenue from the All-Star Game.

THE BEGINNING OF THE MILLER ERA

There were substantial benefit improvements negotiated in 1962 by Lewis successor Robert Cannon, such that a five-year player would receive $125 monthly at age 50 and a ten-year player $250 monthly at age 50.

The plan was getting pretty good now. As Jim Brosnan wrote in his 1962 book The Pennant Race, the plan helped ease the frustrations of defeat as a player could now say, “Well, at least it’s one more day in the pension plan.” It also spurred the challenge as “we all went out to see if we could play well enough to merit the privilege of staying around to collect.”

Not everyone was happy with the improvements, though. This was the first time that benefit improvements weren’t extended to service back to the 1947 inception of the plan. Frank Crosetti and John Schulte filed suit on behalf of some 300 old-time players not fully included in the increases. Norman Lewis was their attorney.

But the big turning point for the pension fund came in December 1966 when newly hired MLBPA executive director Marvin Miller negotiated new concepts and a large funding increase for the players’ pension fund.

Miller was an experienced labor negotiator, particularly in pensions, and he was the first permanent head of the MLPA. When he started, there was virtually no money in the union treasury to pay him. The owners had informally (and illegally) been paying a stipend to the former union advisors out of the remaining proceeds from the All-Star Game. They balked at funding an implacable adversary like Miller.

Miller got the owners to guarantee 100 percent of the pension benefits without any player contributions (then $2 per day of the season, or $344 per year) in exchange for the right to a voluntary check-off for union dues to fund his office in the amount of $344 per year per player. The owners apparently believed the players wouldn’t fund Miller if their pension was fully guaranteed, but they were quite wrong — only one player didn’t go along at the beginning of the 1967 season.

Benefits doubled over their previous levels. Now a ten-year player received roughly $500 per month at age 50, or just under $1,300 per month if he waited until age 65 to collect.

The second conceptual change that Miller brought into play was the scrapping of the 60/40 split of the radio-TV revenue from the World Series and All-Star Games. In replacement, the pension contribution would be a flat lump sum of $4.1 million per year over the term of the labor contract. Miller suspected that perhaps owners were monkeying with the allocation of revenue in the total radio-TV contract, slanting it towards Game of the Week telecasts, which went straight to the owners’ accounts, and shorting the share allocated to World Series and All-Star games, which went to the pension fund.

The stakes were getting bigger now. NBC and Gillette would pay $6.1 million in 1967 and $6.5 million in 1968 for these radio-TV rights. From here it would only escalate. And negotiations would get more dicey.

While the pension fund may not have been receiving its “fair share” of the TV revenue, Miller’s tactic to negotiate a flat pension contribution in 1967 posed a long term risk, as it severed the direct linkage to the TV revenue. Future contribution increases might be tougher to negotiate. And other issues would cloud the pension discussions, such as testing the mettle of the MLBPA and its members.

LABOR STRIFE BEGINS

The boycott of the spring training camps by the players in February 1969 eventually resulted in an agreement whereby the annual pension contribution was increased to $5.45 million and players would be eligible for a pension after four years rather than five. (Miller had calculated that 59 percent of all players never qualified for a pension under the five-year rule.) Benefits were increased so a ten-year player would receive $600 monthly at age 50. Changes were made retroactive only to the 1959 season, which spurred Allie Reynolds to file suit to have improved pension amounts given equally to active and retired players. This action was dismissed in court the same day as the conclusion of the 1969 pension negotiations.

The pension contribution was about one-third of the $16.5 million the owners received in 1969 from NBC in TV revenue for the Game of the Week, All-Star Game and the World Series. Income rose dramatically, though, to $70 million with the 1971 TV contract, and the owners balked at funding pension increases commensurate with this rise in TV money.

With no success at the bargaining table, the players voted 663-10 to authorize a strike. Miller offered to have the impasse submitted to binding arbitration to reach a settlement before the start of the regular season, but was rebuffed by the owners. On April 1 players walked out of spring training camps and the strike spilled over into the regular season — a baseball first — to demonstrate dissatisfaction with the owners’ unwillingness to add fair cost-of-living increases to pension benefits.

Roger Angell in his book Five Seasons aptly described the sense of the times. “The owners declared any accommodation to be an absolute impossibility until a total of eighty-six games and several million dollars in revenue had drained away, whereupon they compromised, exactly as they could have done before the deadlock set in. A last-minute modicum of patience on both sides might have averted the whole thing, but not everyone wanted peace.”

The owners eventually agreed to fund these increases from $500,000 of investment gains in the fund’s securities, after a thirteen-day strike by the players which ended on April 13. The agreement was held up by a discussion over paying players for made-up games or just resuming the season at its point with no back-pay. Sadly, the owners’ frugality won over, with the players indifferent to the “sanctity of the season.”

It was “an unpleasant, but relatively insignificant affair, caused by the owners’ refusal to arbitrate a minor pension issue,” as Angell put it. Some twenty years later it seems an odd issue for the owners to take a strike over. But there was the solidarity of the MLBPA to test.

The alleged Curse of the Bambino struck the Boston Red Sox once again that season as the Sox lost the American League Eastern Division title by a half game due to the uneven number of games played by each team. At least ten-year player Luis Aparicio would get a higher monthly pension under the new agreement to assuage his “goat” label and the memories of titles lost.

The 1972 strike did not even occur during the regular pension negotiations, which took place in 1973, when the owners agreed to kick in higher annual contributions of $6.15 million in 1973-74 and $6.45 million in 1975. A ten-year player would now receive a $710 monthly pension at age 50. But the negotiations now centered almost exclusively around money-contribution levels, not benefit levels. After the contribution was worked out, benefit increases were computed later.

The renegotiation of the pension agreement in 1976 was marred by the owners’ seventeen-day spring training lockout over the issue of free agency following the Messersmith Decision. The owners eventually agreed to an $8.3 million annual funding level, which produced more increases in benefit levels.

Contributions increased to $15.5 million in the 1980 pension agreement, although free agency was left unresolved, and led to the 1981 in-season strike. Players received in-service credit for time lost during the strike to count toward pension benefits.

This contribution level jumped dramatically with the 1985 pension negotiation following a brief two-day in-season strike primarily over the salary arbitration issue. Owners would pay $25 million retroactive for 1984, $33 million during 1985-1988 and $39 million in 1990. Current benefit levels were established retroactive to the 1975 season and pre-1975 retirees got a 40 to 50 percent increase in their benefit levels.

Revenue from television was now jumping to incredible heights and continued linkage with the pension fund contribution levels was hard to justify. Baseball’s television package for six years from 1984-89 with NBC and ABC generated $1.1 billion. CBS will be paying baseball just a shade under this for four years from 1990-93.

A $55 million pension contribution level resulted from the 1990 pension talks.

Although apparently well-funded, the players’ pension plan is not perfect. Minor league playing time is still not covered, for example. There is also the continuing issue of improved benefits to retired players. Hall of Fame pitcher Early Wynn has been outspoken on this issue. After the 1985 pension negotiations, Sports Illustrated reported that Wynn boycotted the induction ceremonies at Cooperstown because he was so disgusted with how the old-timers were treated in the pension increases.

“Modem ballplayers tell us, ‘Too bad, you should have invested better,’ ” fumed Wynn. “But on salaries of 10 thousand to 15 thousand dollars a year, how many investments could you make? They could at least triple the pension for the old guys and give us hospitalization.”

The argument from the MLBPA perspective is that earlier players paid little or no union dues and did not have to endure the emotional and economic hardships of the strikes that resulted in pension improvements.

The issues get touchier as the federal maximum on benefit levels increases with the cost-of-living. The maximum is up to $102,582 from the highly publicized $90,000 level of 1985.

And how are all these generous benefits financed? The pension fund now totals $475 million and is largely invested in the stock market. An article in the Wall Street Journal during 1986 entitled “Plump Pensions in Baseball Are Source of Envy,” discussed how the pension committee left the stock picking to seven money managers. Providing some sound advice on two fronts, the article quoted one pension committee member as saying “We aren’t like Mr. Steinbrenner. We pick the managers and let them play.”