A Second Act in Black Professional Baseball: Ed Bolden, Hilldale, and the Philadelphia Stars

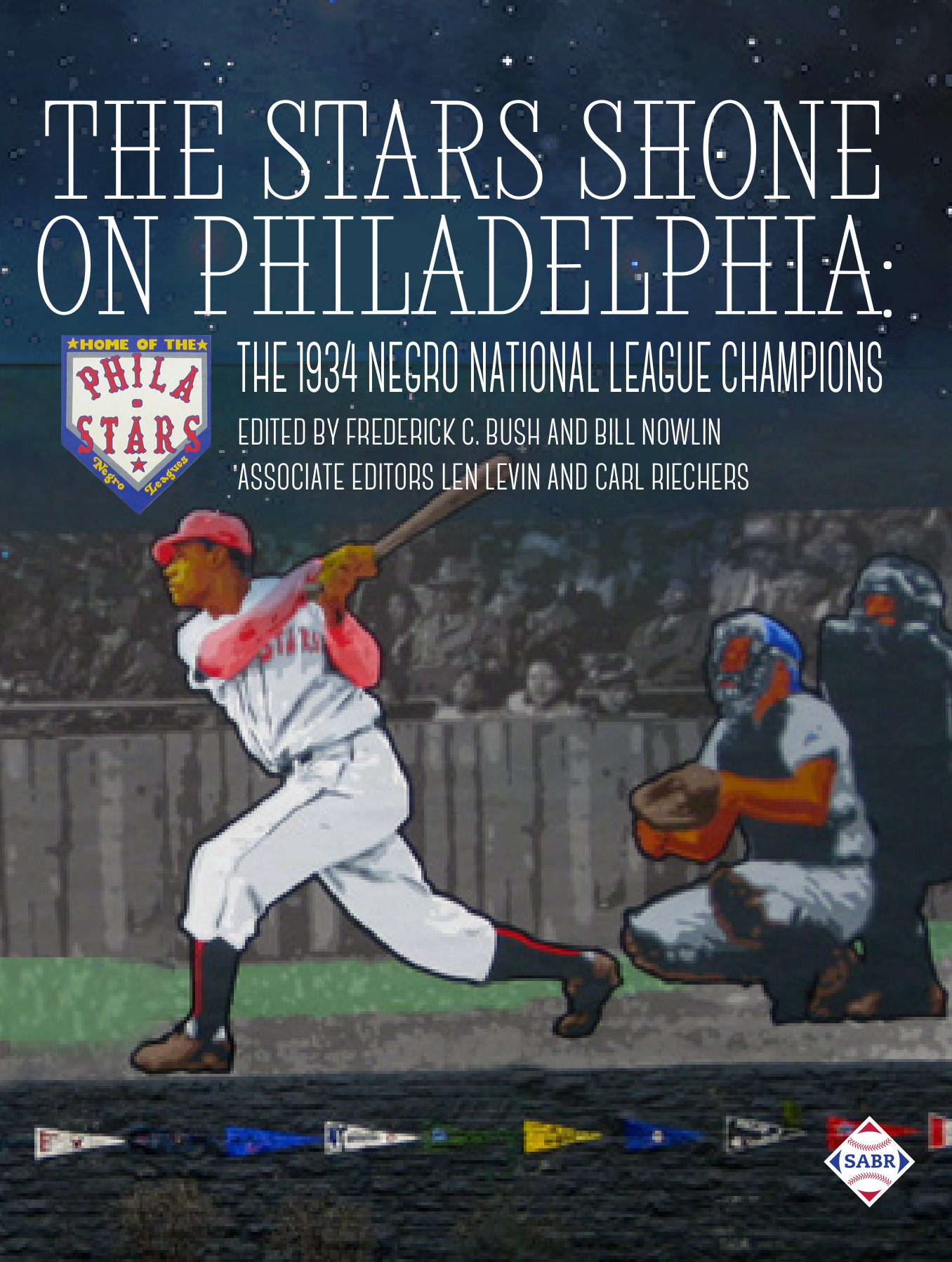

This article appears in SABR’s “The Stars Shone on Philadelphia: The 1934 Negro National League Champions” (2023), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars represented a part of the greater Philadelphia area’s civic and social fabric for two decades. For most of that time, Bolden himself represented the heart of the franchise. His name formed part of the franchise’s official name, and his home address in Darby, Pennsylvania, adorned the franchise’s official stationery. While he worked with a partner, Ed Gottlieb, Bolden served as the franchise’s public face and touchstone. Headlines and stories in the Philadelphia Tribune occasionally called the team the “Boldenmen” and nicknamed the team’s home ballpark in West Philadelphia the Bolden Bowl. Although there were many roster changes over the years, Bolden remained the franchise’s constant through the Great Depression, World War II, and the new challenges presented by the reintegration of the National and American Leagues in what was then known as major-league baseball. Through his work with the Stars, Bolden cemented his place as a valued member of the greater Philadelphia community. He made connections with civic leaders and often welcomed them to attend Stars games. When Bolden died in September 1950, the dignitaries who gathered at his funeral served as a testament to the respect he had garnered throughout his lifetime.1

Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars represented a part of the greater Philadelphia area’s civic and social fabric for two decades. For most of that time, Bolden himself represented the heart of the franchise. His name formed part of the franchise’s official name, and his home address in Darby, Pennsylvania, adorned the franchise’s official stationery. While he worked with a partner, Ed Gottlieb, Bolden served as the franchise’s public face and touchstone. Headlines and stories in the Philadelphia Tribune occasionally called the team the “Boldenmen” and nicknamed the team’s home ballpark in West Philadelphia the Bolden Bowl. Although there were many roster changes over the years, Bolden remained the franchise’s constant through the Great Depression, World War II, and the new challenges presented by the reintegration of the National and American Leagues in what was then known as major-league baseball. Through his work with the Stars, Bolden cemented his place as a valued member of the greater Philadelphia community. He made connections with civic leaders and often welcomed them to attend Stars games. When Bolden died in September 1950, the dignitaries who gathered at his funeral served as a testament to the respect he had garnered throughout his lifetime.1

For Bolden, though, the Stars represented his second act in Black professional baseball. Bolden’s baseball career began in 1911, 22 years before he founded the franchise that bore his name. In that year, Bolden joined a franchise called the Hilldale Daisies that was based near his home in Darby. At the time, Hilldale was a sandlot team full of teenagers; they turned to the then 29-year-old Bolden to keep score for one of their games. Bolden remained with the youngsters and, within a decade, transformed the franchise into one of the most fearsome Black professional baseball teams in the Eastern United States.2

To support the professional Hilldale club, Bolden spearheaded the Hilldale Base Ball and Expedition Company, an all-Black corporation formed in 1917 with other Darby leaders. With Hilldale, Bolden won his first championship, a World Series over the Kansas City Monarchs in 1925. That series marked a rematch between the two teams from the previous season; Kansas City had won the first contest. Alongside highs like the World Series title, Bolden also endured some lows with Hilldale. Most of those down times stemmed from his longtime rivalry with Andrew “Rube” Foster, a Black baseball mogul from Chicago who operated the Chicago American Giants and led the formation of the first Negro National League (NNL) in 1920. Hilldale briefly joined the NNL as an associate-member franchise, but Bolden pulled them out to form his own league, the Eastern Colored League (ECL), in 1923 because he bristled under Foster’s management. The accumulated stresses of running a league and a team led Bolden to have a nervous breakdown in September 1927, but he returned in time for the 1928 season and led the Hilldale franchise for a few more years.

The era from 1928 to 1933 marked the end of Bolden’s first baseball life with Hilldale and the start of his second one with the Stars. During that period, Bolden faced a barrage of criticism as he endured both a very ugly separation from Hilldale and an imperfect return with the Stars. The criticism he faced nearly ended Bolden’s career in Black professional baseball and was a far cry from the praise bestowed upon his death in 1950. The events of that era help to contextualize Bolden’s actions during his career with the Stars and showcase some of the ugly racial issues present within Black professional baseball. Additionally, the events reveal a facet of Bolden’s persona not always evident in his leadership of the Stars. Most importantly, the events that pushed Bolden out of Hilldale help to make the Stars’ quick rise to a title in 1934 all the more remarkable. Bolden had truly faced the depths of life in Black professional baseball and, for a while, a triumphant return with another franchise seemed unlikely. He made the unlikely happen, though not without incurring some sharp criticism and going back on some promises he seemingly had made to a different group of young men in Darby.

In 1928 Bolden’s return to Hilldale after his nervous breakdown came on the heels of a tumultuous year for himself and the league he had formed. Hilldale’s World Series championship in 1925 marked the apex of his time leading both Hilldale and the ECL. Soon, both his team and his league suffered from acute financial problems due to declining attendance. As those financial problems grew, Bolden faced near-constant criticism for decisions he made as the ECL’s leader. In January 1927, the other ECL owners ousted Bolden from his role as the league’s president and replaced him with Isaac Nutter, an attorney from Atlantic City. Bolden continued to serve as the ECL’s secretary-treasurer, but his authority over league affairs had effectively ended. Once Bolden suffered his nervous breakdown in September 1927, he spent a short amount of time receiving treatment from a local hospital. Newspaper columnist W. Rollo Wilson reported that he spoke with Bolden at a football game in the fall of 1927 and correctly predicted that the mogul would return to Hilldale with a fighting attitude. Members of the Hilldale Company, however, did not act as if Bolden would definitely return to the franchise. They chose Charlie Freeman, a former Hilldale player and vice president of the corporation, as the new leader. Freeman made plans for the 1928 season without Bolden’s involvement.3

As Wilson had predicted, Bolden returned to Hilldale in 1928 and was spoiling for a fight since he had no intention of ceding control over the franchise. In March three members of the Hilldale Company, Freeman, Lloyd Thompson, and James Byrd, tendered their resignations. With those resignations, Bolden regained his position as Hilldale’s president, and he hired allies to round out the rest of the franchise’s and company’s leadership. Once he made those moves, Bolden turned his attention to the ECL and withdrew Hilldale from the league. In retaliation, ECL President Nutter accepted a new franchise from the Philadelphia area, the Tigers, and predicted that Bolden would return Hilldale to the organization. Bolden used the pages of both the Pittsburgh Courier and Philadelphia Tribune to explain his actions and to outline the financial losses incurred by Hilldale while it operated as a member of the ECL. His actions seemed prescient; the ECL disbanded in June 1928, and Hilldale made it through the season. Hilldale’s future still seemed precarious since the team continued to struggle to attract large crowds, a symptom of an economic downturn that hit the team’s Black baseball fans and made an outing to the ballpark an unaffordable luxury.4

In early 1929, Bolden tried to repeat his success with the ECL by forming the six-team American Negro League (ANL) with several franchises that also had belonged to the ECL. Bolden served as the ANL’s president and immediately sought to assert his authority over the other league owners and to enact strict laws governing player behavior. While the ANL teams managed to play almost all the games on their schedules, the owners, including Bolden, seemed uninterested in enforcing the league’s laws. The lack of discipline exhibited by ANL players brought Bolden a fresh round of criticism, this time from Syd Pollock, a Jewish booking agent who owned an independent all-Black team called the Havana Red Sox. Pollock wrote an article that ran in the Pittsburgh Courier in which he demanded answers from Bolden and the ANL about why they forbade any ANL team to face his Red Sox. Additionally, Pollock used the opportunity to highlight the ANL’s shortcomings and to argue that the league needed a better leader.5

Overall, 1929 brought a series of challenges, and few successes, for Bolden. Since he failed to uphold his own rules regarding player discipline, on-field fights disrupted many Hilldale games. Bolden also faced biting criticism from the Philadelphia Tribune about his determination to use White umpires. The newspaper implied that Bolden’s use of White umpires fed into ugly racial stereotypes about Black Americans. On top of those issues, Hilldale and other ANL teams, along with teams in the NNL, continued to face financial challenges and low attendance at games. Soon after the 1929 season ended, the stock market crashed and ushered in a prolonged era of financial anxiety. Bolden had tried, and failed, to gather ANL owners for a meeting earlier in October. In February 1930 Bolden and the ANL owners finally gathered at the Republican Club in Philadelphia. They met not to plan for a 1930 season but to formally dissolve the ANL. Hilldale once again faced the prospect of operating independently of a league structure, but Bolden had other plans for his franchise that would ultimately push him out of the sport.6

Prior to the ANL’s dissolution, Randy Dixon reported on rumors of big changes coming to Hilldale. A few months later, Bolden seemed to confirm Dixon’s rumors by announcing that Hilldale had lost its longtime playing field in Darby. In truth, Bolden did not renew the lease at Hilldale Park because he intended to dissolve the Hilldale Company and build a new franchise, Ed Bolden’s Hillsdale Club, with the financial backing of Harry Passon. Passon, a White sports promoter, owned Passon Field at 48th and Spruce Streets in West Philadelphia. The new club would use Passon Field as its home ballpark, and Bolden intended for his Hilldale team to make its debut in the 1930 season. Bolden’s plans never materialized because other members of the Hilldale Company fought back and stopped him from dissolving the franchise. Lloyd Thompson and Charles Freeman, both of whom had resigned after Bolden had returned from his nervous breakdown, came back to save Hilldale. They removed Bolden as the organization’s president; Thompson replaced Bolden and promptly renewed the lease that Bolden had allowed to lapse. Bolden’s baseball career appeared to be over.7

In the eyes of the Tribune’s Dixon, Bolden’s baseball career had permanently ended. Dixon delivered a harsh assessment of Bolden, an assessment that touched upon issues of leadership and race:

At last it looks as if Ed Bolden is fading from the picture. Once an omnipotent figure in Negro baseball. Once the czar of the East. Once the dictator. Once feared and respected. Bolden is through, readers, make no mistake.

The history of the erstwhile postal clerk reads like a dime store bestseller. … It is all history now how Bolden wrecked his team when he went hog wild and administered the oft mentioned boot in the buttocks to several stalwarts, hiring them away from Darby loam with the info that their batting eyes were becoming dulled or their joints were beginning to annoy him with their frequent creaking as the case might have been.

But as if this wouldn’t suffice, Bolden proved himself a traditional cullud [sic] man by playing ‘Uncle Tom’ and taking his advantages to the Nordic faction. … When the American League folded up, Bolden came through with a subsequent statement that Hilldale had dissolved. The Dynasty had ended. He got Nordic backing. Made arrangements to take something that had been nurtured by colored people and was a colored institution and bend it in such a manner to as to fill the coffers of the Nordic. Not maliciously or intentionally perhaps, but such was the case or almost the case.

Lloyd Thompson has stepped in and thwarted Bolden at every turn and now the man who was once a king is now a piker and Ed Bolden is through. We mean THROUGH!8

While Bolden’s career had not ended, he faced several obstacles in any attempt to return to Black professional baseball. One major obstacle was finances – Bolden lacked the capital to build a new team on his own, and the ongoing Great Depression limited the amount of capital available to anyone who wanted to build a new baseball franchise. The bad economy contributed to the demise of the original NNL and a new league, the East-West League, that had attempted to replace it in 1932 and did not last the season. Another major obstacle complicating Bolden’s return to Black professional baseball was Hilldale’s continued existence. Bolden tried to launch a new team with the support of former Hilldale star John Henry “Pop” Lloyd and Harry Passon, the co-owner of a company that had supplied Hilldale’s equipment.9 John Drew, a wealthy African American from Darby, had assumed control of the Hilldale franchise. Drew decided to take command of the team after several members of the financially insolvent Hilldale Company approached him for aid. Lloyd declared that had he “known Hilldale was to have a team [he] surely would not have considered Mr. Bolden’s offers” because he did not want to associate with a new team that challenged an established team.10 Bolden, therefore, suspended his plans to launch a new franchise and spent the 1931 season in the wilderness while plotting his next move.

Although Hilldale fielded a team in 1932, Bolden decided to make his move back into Black professional baseball through the Darby Phantoms. Bolden’s plans for the Phantoms seemed to echo the plans he had executed for Hilldale 20 years earlier and foreshadowed his future ideas for the Stars. He rebranded them Ed Bolden’s Darby Phantoms, received absolute control, and sought to transform them into the region’s next great professional baseball team. The Phantoms struggled under Bolden’s single-minded leadership; nearby, Bolden’s former franchise endured its own set of struggles in what turned out to be its final season. By the middle of June, Drew could no longer pay Hilldale’s players or coaches their salaries, and he raised ticket prices at Hilldale Park in a vain attempt to substitute the gate receipts for the salaries. Drew formally dissolved the Hilldale franchise at the end of July, thereby removing an obstacle to Bolden’s return. The Philadelphia region still appeared to offer fertile ground for a Black professional baseball team, but the Darby Phantoms had thus far failed to give Bolden the entry back into the game he loved.11

In February 1933, Bolden completed his return to Black professional baseball when he attended a meeting at Ed Gottlieb’s office in Philadelphia. Gottlieb, a Jewish booking agent, hosted the meeting to help announce the formation of a new, second iteration of the Negro National League (NNL2). Gus Greenlee, a Black sports promoter from Pittsburgh, was the main force behind the NNL2’s launch, and his Pittsburgh Crawfords represented one of the new league’s franchises. Bolden attended the meeting not as a representative of the Darby Phantoms, but as a representative of a new franchise he had formed with Gottlieb’s support. The new franchise, Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars, aspired to fill the void left by Hilldale’s dissolution and showed that Bolden had given up on the Phantoms. Ironically, the Phantoms still bore Bolden’s name on their official stationery and baseball uniforms. Bolden’s move to a new franchise came as a surprise to the Phantoms’ management and displayed the same edge of ruthlessness evident in Bolden’s behavior since the late 1920s.12

While most of the Philadelphia sports world praised Bolden’s return to Black professional baseball, the Phantoms’ Ray Macey made sure that people did not forget about the promises made to the young team. In a scathing column in the Tribune, Macey hinted that Bolden had engaged in some subterfuge regarding his involvement with the Phantoms. Macey alleged that Bolden had recently asked for his name to remain associated with the Phantoms through his role as an honorary member of the organization. Bolden, however, had not attended any recent meetings, and he sent a letter to a Philadelphia sporting-goods company in which he denied any involvement with the Phantoms baseball team. Macey lamented that many of the young Phantoms players idolized Bolden because he too lived in Darby and had achieved astounding success with Hilldale. The players had fallen under Bolden’s spell and had sacrificed their amateur status to pursue the dream of becoming the next Hilldale. Macey’s comments implied that the Phantoms players could not revert to amateurs, but he wasn’t clear as to the reasons why they could no longer play as amateur ballplayers. Macey furthermore accused Bolden of obfuscation since the players found out through newspaper stories, not through direct communication from Bolden, that he had abandoned them to form a new team.13

Macey’s article got Bolden’s second act with the Philadelphia Stars off to a rough beginning. In addition to abandoning the Phantoms, Bolden butted heads with Greenlee and resisted overtures for the Stars to join the NNL in 1933. While the animosity did not reach the levels seen between Bolden and Foster in the 1920s, the stubbornness Bolden displayed showed that he carried the scars of the battles he had fought when he had led Hilldale. Bolden and the Stars joined the NNL in 1934 and famously enjoyed their best season while also stirring controversy for the ugly incidents that marred the championship series. The seemingly unfair resolutions of those incidents appeared to favor Bolden and the Stars and cost newspaper columnist W. Rollo Wilson his job as NNL commissioner. Bolden often had contentious relationships with other NNL owners and officials; he occasionally held leadership positions within the league, but he never recaptured the total control he had enjoyed with the ECL in the 1920s. Bolden often found himself at the mercy of other NNL officials who exerted more influence within the league and who operated more successful franchises. Ironically, the Stars outlived many of those more successful franchises, giving Bolden a longer foothold within Black professional baseball than most of his peers.

Bolden lived long enough to move past the issues that forced him out of Hilldale and to witness the demise of the Black baseball world of the twentieth century. His death came in September 1950, more three years after Jackie Robinson debuted with the Brooklyn Dodgers and heralded the beginning of the end of racial segregation in professional baseball. As Robinson and other Black players joined franchises like the Dodgers, Cleveland Indians, and New York Giants, all-Black teams like the Stars ceased to serve a purpose within the American sports world. Bolden initially seemed oblivious to this reality, believing that the Stars and other all-Black teams would continue to serve as steppingstones for Black baseball players on their way to successful careers. Like other franchises, however, the Stars struggled to stay relevant, and Bolden saw the team’s best players move on to retirement or to franchises in the formerly all-White minor and major leagues. Bolden’s death not only marked the end of his second act in Black professional baseball, but it also symbolized the end of an era within the Philadelphia sports world. Dignitaries from the region’s sports, political, and cultural world served as Bolden’s pallbearers, and memorials praised his lifetime of achievements with two franchises. The Stars plodded ahead for two more largely forgettable seasons before folding and joining their founder as part of the city’s history.14

Ed Bolden spent most of his life in Black professional baseball and lived through two separate acts in that career, each act punctuated with great heights and depths. In both acts of his baseball career, Bolden displayed a single-minded focus that occasionally escalated into ruthlessness toward players and other officials. Bolden’s decisions in the late 1920s nearly ended his baseball career and marked a period of transition for Black professional baseball. By adapting to a new reality for Black professional baseball, Bolden rebounded and enjoyed a second act with a franchise that bore his name beyond his death.

COURTNEY MICHELLE SMITH is a professor and chair of the history and political science department at Cabrini University in Radnor, Pennsylvania. She is a lifelong fan of the Philadelphia Phillies and the rest of Philadelphia’s sports teams. She is the author of Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia and Jackie Robinson: A Life in American History. Her work also appeared in From Shibe Park to Connie Mack Stadium: Great Games in Philadelphia’s Lost Ballpark and Sports in Philadelphia. Aside from baseball, her research interests include Philadelphia history, Pennsylvania history, and American political history. She spends her free time rooting for the Phillies, Eagles, Sixers, Flyers, and Union.

Notes

1 Michael Haupert, “Ed Bolden.” Biography Project, Society for American Baseball Research, accessed January 17, 2023, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ed-bolden/.

2 Haupert, “Ed Bolden.”

3 Lloyd Thompson, “Keenan Goes West with Rest of League Moguls; May Have Changed His Mind,” Philadelphia Tribune, January 15, 1927; Wilson, “Eastern League Elects Nutter Pres. to Succeed Bolden,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 22, 1927; “Ed Bolden, Hilldale Mentor, Suffers Nervous Breakdown,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 29, 1927; “Bill Francis Signs as Manager of Hilldale for 1928,” Philadelphia Tribune, December 15, 1927; “Charlie Freeman Succeeds Bolden as Hilldale Head,” Chicago Defender, November 26, 1927; “Bill Francis Will Manage Daisies,” Chicago Defender, December 17, 1927; “Ed Bolden Suffers Nervous Breakdown,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 1, 1927; Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 29, 1927; “Bolden ‘Let Out’ as Head of Hilldale Baseball Club,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 10, 1927; Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, December 10, 1927.

4 Edward Bolden, “Bolden Back in Perfect Health, Proffers Views,” Philadelphia Tribune February 2, 1928; Randy Dixon, “Hilldale and Giants Quit Eastern Loop,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 15, 1928; “Freeman Out as Hilldale Quits Eastern League,” Chicago Defender, March 17, 1928; “Nutter Backed by Magnates Defies Bolden,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 15, 1928.

5 “Eastern League, Punctured Already, Gets Flat Tire,” Chicago Defender, April 21, 1928; Wilson, “Eastern League Will Continue,” Chicago Defender, April 28, 1928; “Eastern League Bubble Bursts as Moguls Disagree,” Chicago Defender, May 5, 1928; “Eastern League Disbands,” Pittsburgh Courier April 21, 1928; “Jap Champs to Play Hilldale,” Pittsburgh Courier, May 12, 1928; “Eastern League Disbands; Fate Long Predicted,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 18, 1928; Randy Dixon, “Sport Sidelights,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 18, 1928; “Veteran Outfielder and Star Pitcher Will Play for Daisies; Report Soon,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 29, 1928; “Hilldale Club Battles House of David Sat.,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 28, 1928; “Bolden’s Pets Wreck House of David; Divide with the Bacharachs at the Seashore,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 5, 1928; “12,000 Watch Hilldale and Rivals Split,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 19, 1928; “Fandom Eagerly Awaits Initial Fray of Series to Determine Supremacy,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 13, 1928; Dixon, “Sport Sidelights,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 20, 1928; Courtney Michelle Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017), 46-53; “Eastern League Formed, Grays Join,” Pittsburgh Courier, January 19, 1929; Wilson, “American Negro League Flays Barnstorming; Reserves Named,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 2, 1929; “A.N. League Makes Laws,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 8, 1929; “Possibility of New Baseball League to Replace Defunct Eastern Circuit Looms in Conclave Here Next Month,” Philadelphia Tribune, January 3, 1929; “System of Rotating Umps Agreed by Baseball Magnates at Parley Here,” Philadelphia Tribune, February 28, 1929; “A.N. League Makes Laws,” Pittsburgh Courier, June 8, 1929; “Baseball War Looms as East Raids Western Clubs,” Chicago Tribune, July 13, 1929; Dixon, “Sport Sidelights,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 25, 1929; “Baseball War Between American and National Negro Leagues Looming,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 15, 1929; Dubbia Ardee, “Antics of Cum Posey Are Likely to Harm Future of Organized Baseball,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 1, 1929; Syd Pollock, “Syd Pollock Calls New League ‘Joke,’ Makes Grave Charges,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 3, 1929; “Baseball War Between American and National Negro Leagues Looming,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 15, 1929.

6 “Negro Umps at Hilldale,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 3, 1929; “Hilldale Again,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 8, 1929; Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 12, 1929; Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 30, 1929; “American Negro League Votes to Disband,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 22, 1930; “American Negro League Disbands; Teams Enter Independent Field,” Philadelphia Tribune , February 20, 1930.

7 Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, October 12, 1929; Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, November 30, 1929; “American Negro League Votes to Disband,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 22, 1930; “American Negro League Disbands; Teams Enter Independent Field,” Philadelphia Tribune, February 20, 1930; “Clan Darby Status in Doubt,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 5, 1930; Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 19, 1930; Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 26, 1930; “Bolden Loses in Effort to Bust Daisies,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 3, 1930; Smith, 53-59; “Ed Bolden to Head Up New ‘Hillsdale’ Club,” Pittsburgh Courier, April 19, 1930; “Ed Bolden to Organize New Ball Outfit,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 10, 1930; Dixon, “Sport Sidelights,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 10, 1930; “Lincoln Giants, Hilldale and Bolden’s Latest Club to Furnish Pastime,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 17, 1930; Dick Sun, “Original Hilldale Club to Open Home Season on May 3 with Camden Nine,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 24, 1930.

8 Dixon, “Sport Sidelights,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 24, 1930.

9 Mark Ribowsky, A Complete History of the Negro Leagues 1884 to 1955 (New York: Carol Publishing Group, 1995), 139-156; Dixon, “Sports Sidelights,” Philadelphia Tribune, January 29, 1931.

10 Dixon, “Sports Sidelights,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 5, 1931.

11 Smith, 60-65.

12 Smith, 66-69.

13 Ray Macey, “Phantoms Ride Bolden for Quitting Team,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 23, 1933; Smith, 70.

14 Haupert, “Ed Bolden”; Smith, 148-153.