Before There Was Radio: How Baseball Fans Followed Their Favorite Teams, 1912-1921

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2021 as part of the SABR Century 1921 Project.

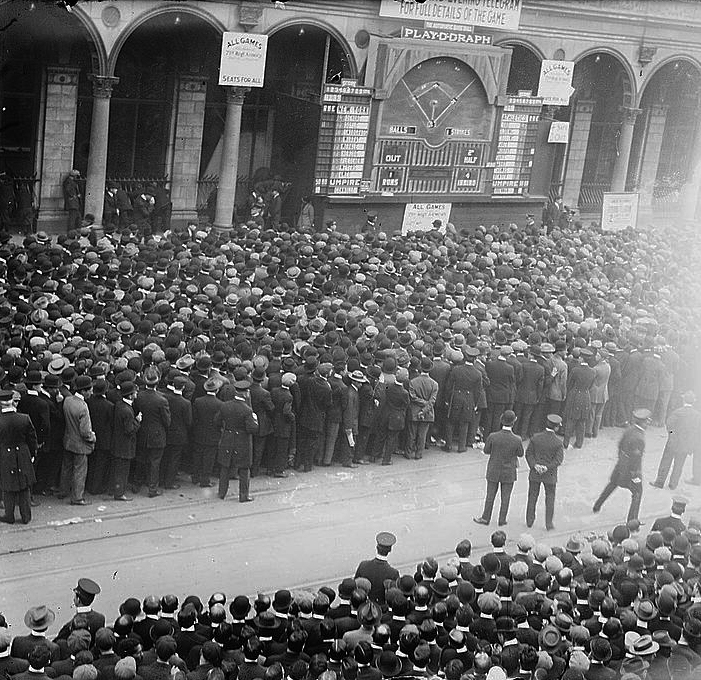

A crowd gathers outside the New York Herald newspaper building to watch a billboard diagram of a game during the 1911 World Series between the Philadelphia A’s and New York Giants. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS)

If you were a major-league baseball fan in the 1910s, you were living at a time before commercial radio had come along. With no way to listen to the play-by-play at home (and no expectation that such a thing was even possible), you had to find other options when you wanted to know how your favorite team was doing. The best way, of course, was to go to the ballpark and watch the game in person, but not everyone could get the time off from work; there was no 40-hour workweek yet and putting in 50 or more hours a week was common in some jobs. And even if you had an understanding boss, there were still expenses to consider: By modern standards, tickets seemed cheap (even World’s Series seats ranged from 50 cents to $3), but keep in mind that the average worker’s salary was much less than what people earn today. For example, in 1915, the annual salary for teachers in most cities was less than $600,1 and many other jobs paid no more than $700 a year.2 Thus, attending a ballgame was reserved for special occasions.

Some fans who could not attend in person would go downtown and gather in front of the offices of the local newspaper, where they eagerly awaited the latest scores. The bigger cities often had a group of newspaper offices in close proximity to each other; in Boston and other large cities, this area was sometimes referred to as Newspaper Row. It became a place for fans to socialize, as everyone stood on the street in front of their favorite publication, hoping for good news about the game. When the newspaper received the latest scores from a telegrapher at the ballpark, a newsboy would write the information on a bulletin board, updating it every inning.3 Some newspapers also had someone with a megaphone calling out the updates as they were received. In either case, the fans would cheer whenever the news was good, or express their disappointment when it wasn’t.

Even in small towns, fans knew their local newspaper was a good place to go to, since it probably had a leased wire to either the United Press or the Associated Press, both of which transmitted the latest scores from ballparks all over the region. But while most people of that era knew what wireless telegraphy was — even if they didn’t use it themselves — they probably didn’t know how information about the game made its way so quickly from their local park to their local paper.

One thing that helped was a specialized code, called the Phillips Code, that the wire services utilized; it had abbreviations for the most frequently used words in current events, weather, and sports. This enabled the Associated Press and United Press telegraphers to transmit the news with greater speed. (Interestingly, some of these abbreviations, first created by Walter P. Phillips in 1879, live on to this day on social media — for example, POTUS for President of the United States, and SCOTUS for the Supreme Court.)4

The telegraphers also had baseball-related abbreviations they could use when transmitting the game summaries: “Bob” referred to a base on balls; when a pitching change occurred, it was transmitted as “Npf” (now pitching for …); and as might be expected, an umpire was abbreviated as “Ump.”5 The telegraphers did not just restrict themselves to who was winning or who made an error. They could also describe the emotions of the fans at the park — perhaps there was great excitement (“gx”), or fans thought a play was wonderful (“wdf”), or if the team was playing poorly, fans might react unfavorably (“ufby”).

Of course, it was often impossible for fans to wait around at a newspaper building, which meant their only other option was buying a copy of the newspaper itself. Back in 1915, newspapers published morning, midday, afternoon, and evening editions; and if there was a big sports event (like a World’s Series), there was even a late-night edition with the very latest scores, and when there was what we today call “breaking news” about a major story, there might be a special edition called an “extra.” Whether you hung out on Newspaper Row or bought the latest paper from your local newsstand, waiting for the scores and the game summaries was just a part of life for those fans who couldn’t be at the ballpark.

But in the period from 1912 onward, there was one other option, although it still wasn’t widely known or widely utilized. There was a growing number of amateur wireless operators (what we today would call ham radio operators), most of whom still communicated by Morse code, but a few were experimenting with voice. And some of these wireless enthusiasts were also baseball fans. They got to know the telegraphers who transmitted the game reports from local ballparks, and whenever there was information to share, they sent it out to their friends. However, this strategy worked only if the friends also had a receiving set; fortunately, throughout the 1910s, more people were getting involved with wireless themselves, while others had a family member who could give them the scores.

Meanwhile, on college campuses, amateurs were becoming an information conduit for their fellow sports fans. For example, at Tufts College in Medford, Massachusetts, the Tufts Wireless Society, which made its debut in January 1912, soon became known for transmitting the latest football and baseball scores. During the 1912 World’s Series between the Red Sox and the New York Giants, the scores and updates were received and then posted at Robinson Hall, home of the Engineering Department.6 Students at other colleges also embraced the role of keeping their fellow students (and faculty) informed: In the summer of 1915, some Massachusetts Institute of Technology students were attending a camp in Maine. Lacking easy access to a local newspaper, they received the latest news headlines and baseball scores by wireless and posted them on a bulletin board for everyone to read.7 And it was not just on college campuses that this was taking place: A New Jersey amateur named Fred Dennis installed amateur wireless equipment in his home, which enabled him to receive up-to-date information about the 1915 World’s Series; he made sure to share the latest scores with his friends and neighbors — which they undoubtedly appreciated.8

In fact, throughout 1915 and 1916, it seemed that nearly every month there was another newspaper or magazine story about an amateur who was helping local fans to follow their favorite teams. In 1916 there was even an interesting collaboration between an amateur operator named Gustave Werner (whose amateur call letters were 1PH) and his local newspaper, the Lynn (Massachusetts) Evening News. Werner was widely known in Lynn, a city about 15 miles north of Boston. A member of the Amateur Radio Relay League (ARRL), he was also a firefighter with the Lynn Fire Department. Werner had already used wireless to notify his fire chief when he spotted a chemical fire in early March 1915,9 but on a lighter note, he made arrangements with the Lynn Evening News to transmit the latest baseball scores every night — results from the National, American, and Eastern League games. Werner told the press that his station had a radius of about 30 miles, and as soon as the newspaper received the scores from the Associated Press, he would make them available, around 6 o’clock each evening.10

Still, although amateur radio was developing a strong niche in some cities, the average person probably had little familiarity with it, unless a friend or family member had a receiving set. In that decade before commercial radio came along, the majority of the fans relied on print journalism to keep up with their favorite team; most major cities had more than one newspaper (Boston in the 1910s had eight), and every city had its own popular local sportswriters who not only discussed wins and losses; they interviewed local players and gave fans more insight into their favorite team.

The writers also made good use of the information they received by wireless. After all, this was still a time before air travel, when ballplayers, writers, and fans relied on trains to get from point A to point B. (Driving was not always practical: even if you could afford a car, many cities lacked good roads and the top speed of the average 1915 Ford Model T was about 40 mph, which meant getting to your destination might take a while.) That is why the telegraphers who sent the game reports to affiliated newspapers were a lifeline for the baseball writers, helping them to keep up with the pennant races and find out how teams in distant cities were doing, and making it possible to provide the readers with reports from all over the major and minor leagues.

The Associated Press, aware that interest in baseball was intense, especially around the time of the World’s Series, kept improving its technology, so that results would come in faster and reach more places. By 1918, the AP’s engineers had installed a telegraph circuit of more than 30,000 miles, 500 miles longer than in 1917.11 And the AP’s chief competitor, United Press, was also enhancing and expanding; UP even placed advertisements in local newspapers to claim that its transmissions of baseball scores were faster and more accurate than those of other services.12 Some newspapers decided not to choose one or the other: in Topeka, Kansas, the State Journal declared that its baseball coverage was the best in the region because it made use of both services.13

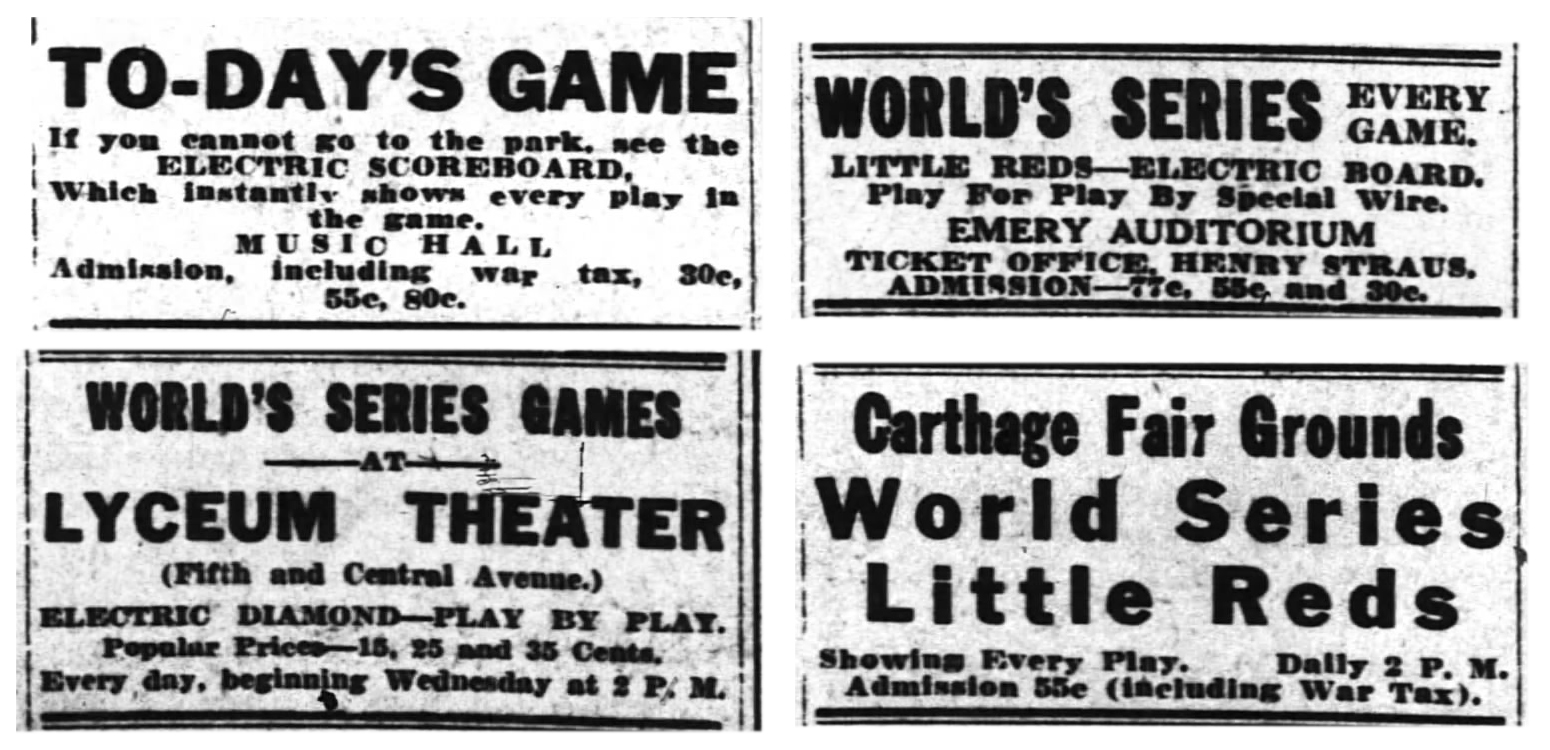

Baseball fans in Cincinnati could visit a variety of neighborhood theaters, music halls, and fair grounds to find an electronic scoreboard showing near-instant results from Game One of the 1919 World Series throughout the city. (CINCINNATI ENQUIRER, OCTOBER 1, 1919)

It is worth noting that if you were around for the birth of commercial broadcasting, you would not have called it “radio” — the most common terms for what you were listening to were either “wireless telephone” or “radio telephone,” and some newspapers combined the two into “radiophone.” And rather than “broadcasting,” the term “sending” was more common; a radio station was often called a “sending station” in those formative years. Further, radio receivers were not yet being mass-produced. If you wanted one, you would have had to build it yourself (or find a technologically-skilled person to do it for you).

And that brings us to 1920. But before commercial radio made its debut that year, in Detroit (8MK), Medford Hillside, Massachusetts (1XE), and Pittsburgh (8XK, soon to be known as KDKA), amateur stations and college stations continued to provide scores and updates. In May 2020, the University of Pittsburgh’s 8YI was sending out baseball scores every evening.14 In fact, several months before KDKA became the first station to provide a live baseball broadcast by radio, the pioneering Pittsburgh station had already been broadcasting scores and updates.15 But broadcasting a live baseball game changed everything for the fans. Hearing scores and updates was one thing, but hearing actual play-by-play, voiced by an announcer who was at the ballpark, was something else entirely.

In 1921 only a small number of commercial stations were on the air, and people who were able to listen to any of them felt fortunate to be on the cutting edge of something so amazing. In fact, if you were reading about commercial radio in those first several years, adjectives like “magical” and “wonderful” and “amazing” were quite common. Radio was the first mass medium to bring listeners to an event in real time — something few people had ever thought possible. Soon, the “Radio Craze” would sweep the country and new stations would spring up from coast to coast. Soon, many sporting events, including baseball, would be heard in cities of all sizes. But in the summer of 1921, those fans who had their own receiving sets didn’t know what the future would bring. They did know, however, that they were on the verge of a great adventure, and radio would take them there.

DONNA L. HALPER is an Associate Professor of Communication and Media Studies at Lesley University in Massachusetts. She joined SABR in 2011, and her research focuses on women and minorities in baseball, the Negro Leagues, and “firsts” in baseball history. A former radio deejay, credited with having discovered the rock band Rush, Dr. Halper reinvented herself and got her PhD at age 64. In addition to her research into baseball, she is also a media historian with expertise in the history of broadcasting. She has contributed to SABR’s Games Project and BioProject, as well as writing several articles for the Baseball Research Journal.

Notes

1 “Teachers’ Salaries and Cost of Living,” National Education Association of the United States, July 1918: 43.

2 “The Life of American Workers in 1915,” Monthly Labor Review, Bureau of Labor Statistics, February 2016. https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2016/article/the-life-of-american-workers-in-1915.htm.

3 “Bob Dunbar’s Sporting Chat,” Boston Journal, October 11, 1913: 9.

4 “Messages by Code,” Dallas Morning News, February 22, 1903: 9.

5 “The Phillips Code,” Boston Herald, March 26, 1922: 6D. In an effort to promote the Phillips code as a useful method for anyone who needed to take notes, the Herald reprinted the original abbreviations and various updates during that entire month.

6 “Tufts’ Wireless Station,” Boston Globe, February 16, 1913: 25.

7 “Wireless at Massachusetts ‘Tech’ Camp,” Electrical Experimenter, August 1915: 287.

8 “Fair Haven News,” Daily Register (Red Bank. New Jersey), October 13, 1915: 11.

9 “Fireman Learned About the Fire by Wireless,” Boston Globe, March 2, 1915: 6.

10 “Baseball Scores by Wireless,” QST, June 1916: 125.

11 “A 30,500 Mile Telegraph Circuit,” Electrical Experimenter, January 1918: 600.

12 Advertisement in the Daily Gazette (Salina, Kansas) October 9, 1919: 1.

13 “Wire Direct to Topeka,” State Journal (Topeka, Kansas) October 1, 1919: 1.

14 C.E. Urban, “The Radio Amateur,” Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, May 16, 1920: Section 6, 2.

15 “Market by Wireless, Direct to the Farm, Is Service Now Offered,” Echo (Ligonier, Pennsylvania), May 25, 1921: 1.