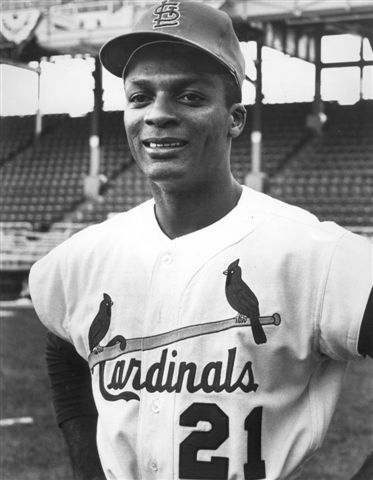

Curt Flood’s 1969 Trade to the Philadelphia Phillies

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in 2022 as part of SABR’s Baseball and the Supreme Court Project.

The 1969 season was Curt Flood’s twelfth, and ultimately final, season as the regular center fielder for the St. Louis Cardinals. His trade to Philadelphia led to Flood testing the legality of the reserve clause under which a player was effectively the property of his team’s owner.

The 1969 season was Curt Flood’s twelfth, and ultimately final, season as the regular center fielder for the St. Louis Cardinals. His trade to Philadelphia led to Flood testing the legality of the reserve clause under which a player was effectively the property of his team’s owner.

In 1968, Sports Illustrated referred to Flood – a seven-time Gold Glove award winner – as baseball’s best center fielder. However, the Cardinals lost the 1968 World Series to Detroit, with Flood misjudging a liner by Jim Northrup in the 7th inning of Game 7. The ball went over Flood’s head for a two-run triple to break a scoreless tie in Detroit’s favor, and Detroit ultimately won the game, and the Series, with a 4-1 victory.

Flood felt that his relationship with the Cardinals’ front office became increasingly strained during 1969. Flood and the Cardinals engaged in an acrimonious contract dispute in the spring of 1969. Flood was a holdout when spring training began, and notes in his autobiography that his holdout for a $90,000 contract infuriated the team’s owner. Flood also missed an important public function in May, drawing the wrath of the front office and a $250 fine. Flood was angered because the front office failed to take into account the fact that he had been severely spiked during the previous night’s game and had spent a restless night dealing with both the pain and the effects of the painkillers he was given. As August of 1969 turned into September, the local press reported comments from Cardinals’ veterans criticizing the front office for giving up on the team’s chances to make the postseason by making manager Red Schoendienst play several rookies late in the season. Flood was the source of much of that criticism and although his name was never mentioned, the Cardinals front office suspected that he was responsible for those comments.

On October 7, 1969, the Cardinals traded Flood – along with catcher Tim McCarver, outfielder Byron Browne, and relief pitcher Joe Hoerner – to the Phillies for first baseman Dick Allen, pitcher Jerry Johnson, and infielder-outfielder Cookie Rojas. In 1969, players were still bound to a team for life by the so-called “reserve clause.” A player was essentially a team’s property in perpetuity unless the team chose to trade or release him. The Phillies reportedly offered Flood a $10,000 raise, to $100,000. Flood, calling Philadelphia the nation’s “northernmost Southern city,” refused to report to the Phillies. In order to replace Flood in the trade, the Phillies later selected two minor leaguers from the Cardinals, including Willie Montanez.

Flood consulted Marvin Miller, the director (since April 1966) of the Major League Baseball Players’ Association (MLBPA), and they discussed the possibility of suing major league baseball to overturn baseball’s 1922 exemption from the Sherman Anti-Trust Act. In Miller’s autobiography, he recalls warning Flood that given the courts’ history of bias towards the owners and their monopoly, the odds were heavily against Flood winning, and that a lawsuit would be both expensive and time consuming. He also noted that the owners would likely blackball Flood, even if he won.

Despite Miller’s warnings, on December 13, 1969, Flood went to the MLBPA’s executive committee meeting in Puerto Rico to discuss suing major league baseball in a challenge to the reserve clause. After Flood’s meeting with the MLBPA, its executive committee voted unanimously to back Flood (including paying his legal expenses) and Flood filed his lawsuit against major league baseball, seeking to be declared a free agent.

During pre-trial hearings, the Phillies told the District Court judge they were willing to have Flood report for spring training and to play the 1970 season without prejudice to his lawsuit. In response, Flood’s counsel said that this was exactly what Flood did not want to do, stating that Flood did not want to be treated like cattle. Flood took his challenge all the way to the Supreme Court, ultimately suffering a 5-3 defeat.

Although Flood said in 1970 he did not expect to play professional baseball again, in 1971 Flood was traded to the Washington Senators, and agreed to a contract with the team. However, the drain of the lawsuit, sitting out the previous season, and his alleged frequent drinking had made him a shell of the player he was in St. Louis. He left the Senators in late April of 1971 and retired from baseball.