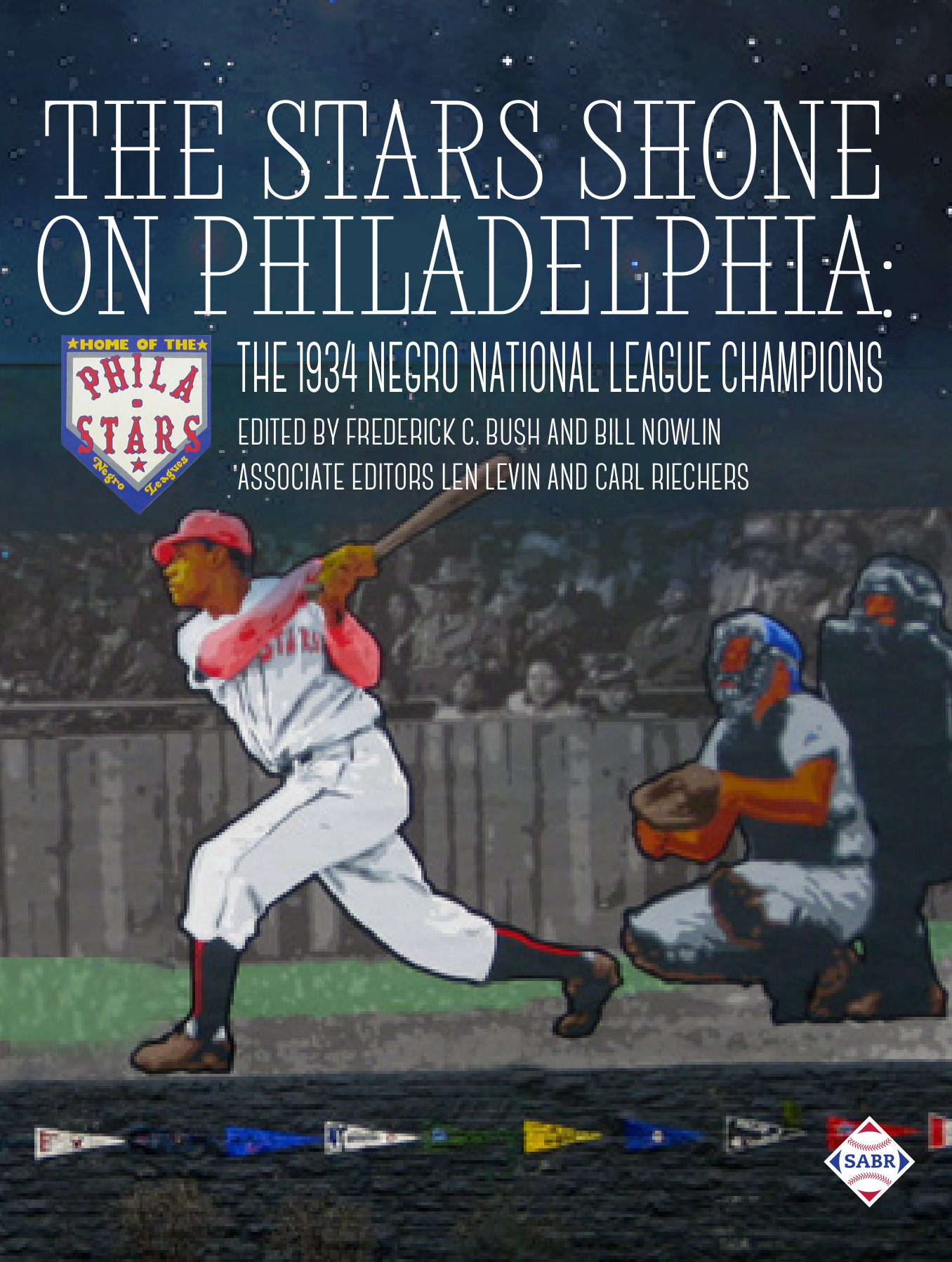

Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars: A Franchise in the Shadows of Its Peers

This article appears in SABR’s “The Stars Shone on Philadelphia: The 1934 Negro National League Champions” (2023), edited by Frederick C. Bush and Bill Nowlin.

Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars existed for almost exactly 20 years. They were formed in February 1933, in the middle of the Great Depression and the transition from Herbert Hoover to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Stars formally ceased operations in the spring of 1953, in the middle of the National and American Leagues’ imperfect yet steady progress toward integration. During those intervening 20 years, the Stars experienced the highs and lows common to all Negro League teams in the 1930s and 1940s. They offered Black baseball players opportunities denied to them in the two leagues then deemed “major.” Ironically, once those leagues welcomed Black players, the Stars no longer had a place within the American sports world. They represented a relic of a segregated world that started to disappear in the late 1940s. The Stars’ death happened quietly; no one seemed to mourn their passing in 1953 because the sports world had moved on from the Negro Leagues. However, the Stars’ existence mattered, and the franchise’s history tells a tale about the triumphs and obstacles Negro League teams faced in the middle of the twentieth century.

Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars existed for almost exactly 20 years. They were formed in February 1933, in the middle of the Great Depression and the transition from Herbert Hoover to Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The Stars formally ceased operations in the spring of 1953, in the middle of the National and American Leagues’ imperfect yet steady progress toward integration. During those intervening 20 years, the Stars experienced the highs and lows common to all Negro League teams in the 1930s and 1940s. They offered Black baseball players opportunities denied to them in the two leagues then deemed “major.” Ironically, once those leagues welcomed Black players, the Stars no longer had a place within the American sports world. They represented a relic of a segregated world that started to disappear in the late 1940s. The Stars’ death happened quietly; no one seemed to mourn their passing in 1953 because the sports world had moved on from the Negro Leagues. However, the Stars’ existence mattered, and the franchise’s history tells a tale about the triumphs and obstacles Negro League teams faced in the middle of the twentieth century.

The February 9, 1933, edition of the Philadelphia Tribune carried the news of the birth of Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars. A headline announced the franchise’s creation, and the accompanying article shared a few interesting details as to how it came into existence.1 Formally, the franchise was born during a meeting of Black baseball leaders in Ed Gottlieb’s office. Gottlieb was a (White) Jewish booking agent and sports promoter who worked in Philadelphia, and he was to provide financial support both to the Stars and to the Negro National League II (NNL2). The NNL2 was looking to build an Eastern division, and the Stars were projected to be one of the teams to populate it. Gottlieb worked behind the scenes in scheduling games and managing finances, while Bolden served as the franchise’s public face. Bolden, whose name remained part of the franchise’s official name throughout its existence, was a Black resident of nearby Darby, Pennsylvania, who had already made a name for himself in Negro League baseball. He had steered the Darby-based Hilldale Daisies to prominence in the 1910s and 1920s before an ugly falling-out ended his tenure with Hilldale a few years before that franchise folded. Hilldale’s demise opened the Philadelphia market and gave Bolden the opportunity to return to Black professional baseball as well as to reestablish himself as one of the top Black baseball moguls in the country.

Under Bolden’s guidance, the Stars enjoyed a successful inaugural season that saw them win every series and earn praise as the “[b]est balanced Colored attraction in baseball.”2 Bolden skillfully used his connections within the Black baseball world to sign established and talented players like Dick Lundy, Webster McDonald, Biz Mackey, Jud Wilson, Jake Stephens, Porter Charleston, Dick Seay, and Cliff Carter. With their talented roster, the Stars amassed a winning record by defeating local semipro and professional all-White baseball teams. The Stars also defeated Negro League clubs like the Pittsburgh Crawfords and semipro Black teams like Passon Club, owned by Philadelphia businessman Harry Passon. Bolden’s Stars also developed a rivalry with Passon’s other club, the Bacharach Giants. The Stars fared well against their rivals and cemented their status as the city’s next great Black baseball team.3

In addition to relying upon his connections within the sports world, Bolden also used his connections to columnists in Black newspapers, particularly the Pittsburgh Courier and the Philadelphia Tribune, to help build a fan base for his new franchise. Bolden had honed those connections during his years with Hilldale, and his team’s success helped to ensure favorable coverage in the city’s largest Black newspaper. Prior to the season, columnist W. Rollo Wilson, who had hinted at Bolden’s comeback in a column published on February 4, 1933, declared that “[u]niform makers, sporting goods houses [and] similar concerns” had entered into a bidding war for the Stars’ business.4 In the Philadelphia Tribune, Randy Dixon lauded Bolden’s roster as a “choice coterie of diamond laborers whose past exploits and present records insure [sic] [Bolden] of fielding an aggregation that will doff the sombrero to no rival cast.”5 As the Stars accumulated victories, Dixon continued his praise for Bolden and declared that the team had “stepped in the front rank of eastern Negro baseball teams.”6 Throughout the 1933 season, the Philadelphia Tribune provided regular, and laudatory, coverage of the Stars as they faced well-known teams like the Pittsburgh Crawfords and local teams like the Bacharach Giants. With that coverage, the Stars built a fan base, and Bolden renewed his connections with a newspaper that provided a critical link to the fans who attended Stars games.7

Perhaps the wisest decision Bolden made during the Stars’ inaugural season was to keep the franchise out of the new NNL2. Bolden had bad experiences operating within league structures when he owned the Hilldale team, and he correctly saw that an independent status was the best option for his new club. Gus Greenlee, who operated both legal and illegal businesses in Pittsburgh, steered the creation of the NNL2 and envisioned a “national” league with franchises stretching from Chicago eastward to Philadelphia. His legal businesses included the Pittsburgh Crawfords, an entry in the NNL2, and the Crawford Grill nightclub. Greenlee’s illegal businesses included the numbers lottery and selling alcohol during the Prohibition Era. His launch of the new league came at the same time as he stood trial in Pittsburgh for charges stemming from his illegal gambling business. Though the jury found Greenlee not guilty, his court case foreshadowed continued legal troubles for himself and an unsettled inaugural season for the NNL2. The NNL2 seemed to fall apart in the middle of the season when Cumberland Posey of the Homestead Grays, another Pittsburgh-based franchise, allegedly signed two players claimed by the Detroit Stars. As a result, the NNL dismissed the Grays from the league. Disputes between Posey and John Clark, one of Greenlee’s associates, spilled over into the pages of the Pittsburgh Courier and painted the picture of a league in disarray.8

Greenlee’s efforts to build the NNL2 were not a total failure, and the league he founded did manage to survive for the next 15 seasons. His best decision came when he oversaw the first East-West Game, an event that became the annual All-Star Game for the Negro leagues and a premier showcase for some of the best Black baseball players in the country. To help generate interest for the game, Greenlee had ballots printed in the Pittsburgh Courier, the Philadelphia Tribune, and other Black newspapers. The East-West Game was a huge success; the game was played in Comiskey Park, the home of the Chicago White Sox. Notable players at the first East-West Game included Oscar Charleston, Satchel Paige, Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, Judy Johnson, and James “Cool Papa” Bell. Even though the Stars did not belong to the NNL2, the East roster included four members of the squad – Biz Mackey, Jud Wilson, Dick Lundy, and Rap Dixon. Greenlee, furthermore, did not give up on his determination to include the Stars in the NNL2, and his determination paid off when Bolden and Gottlieb added the franchise to the league prior to the 1934 season.

The Stars’ 1934 season, the best campaign in their history, began with their ungraceful entry into the NNL2. At a meeting in Philadelphia in February 1934, the NNL owners seemed poised to welcome two Philadelphia teams into the league, the Stars and the Bacharach Giants. Bolden, however, objected to the Bacharach Giants’ entry, and Harry Passon withdrew his team’s application. As Bolden explained, he did not believe that Philadelphia could successfully support two league franchises, so the Stars would not join the NNL2 if the other owners accepted the Bacharach Giants into the fold. Bolden made further waves at the meeting by arguing against a stipulation that each league franchise make financial deposits. The other owners insisted on those deposits because the money could help protect them against fines and defaults in players’ earnings. Bolden did receive some good news when the other NNL2 owners elected the newspaper columnist W. Rollo Wilson, with whom he had a close working relationship, as the league’s commissioner. That decision, along with Gottlieb’s continued status as a scheduler for many NNL games and as an overseer for the league’s finances, helped cement Philadelphia’s special status within the league. Such as status came in handy at the end of the season when the commissioner needed to make key decisions involving the championship series.9

For the 1934 season, the NNL had both full and associate members. The full members included the Stars, Pittsburgh Crawfords, Cleveland Red Sox, Nashville Elite Giants, Newark Dodgers, and Chicago American Giants. After withdrawing his franchise’s application as a full NNL2 member, Passon brought the Bacharach Giants into the league to join the Homestead Grays, Memphis Red Sox, and Birmingham Black Barons as associate members. To help determine the league champion, the owners divided the 1934 regular season into two halves. After the regular season ended, the winners of the two half-seasons would meet to determine the NNL2 champion. As it had during the previous season, the league again experienced some instability in the 1934 season. The Cleveland Buckeyes withdrew from the circuit during the second half of the season, and the Nashville Elite Giants did not have any home games on the second-half schedule. Similarly, the league’s attempt to expand into the Baltimore market with the Baltimore Black Sox failed when other league teams refused, for financial reasons, to travel to Baltimore for games.10

Due to the Stars’ ability to consistently draw large crowds to home games and to their talented roster, the franchise remained insulated from the troubles plaguing other league teams. The Stars played many of their home games at Passon Field, at 48th and Spruce Streets in West Philadelphia. Passon Field underwent renovations in preparation for the Stars’ games; the improvements included the installation of 4,000 new seats. Five thousand fans greeted the Stars at their home opener, a 12-0 victory over the Newark Dodgers. In addition to watching their team shut out the Dodgers, the Stars’ fans enjoyed pregame festivities featuring the O.V. Catto Elks Band. With the exception of starting pitcher Stuart “Slim” Jones, every player in the Stars lineup notched at least one hit, and the team’s offense prowess drove the Dodgers’ starting pitcher from the game in the fifth inning. The Stars’ home opener set the tone for the rest of the season. Most importantly, it introduced Slim Jones to Philadelphia’s Black baseball fans and to the rest of the NNL2.11

Born in Baltimore in 1913, Jones emerged as one of the best pitchers in the NNL2 and as one of the best players ever to don a Stars jersey. Slim earned his nickname because he stood 6-feet-6 inches and weighed only 185 pounds. Prior to joining the Stars in 1934, Jones spent the 1932 and 1933 seasons with the Baltimore Black Sox and the 1933-34 winter season with a team in Puerto Rico.12 Despite his youth and inexperience, Jones often started important games for the Stars during the 1934 season. As an example, the rivalry between the Stars and the Bacharach Giants carried over from the 1933 season, and Jones started the first and fourth games of a five-game series between the two foes. Jones pitched a shutout in both games; he allowed a total of seven hits and posted double-digit strikeouts in each. Not surprisingly, Jones was one of the pitchers chosen to represent the East team at the second annual the East-West Game. Jones combined with two other pitchers on the East team, including Leroy “Satchel” Paige, on a 1-0 shutout of the West team. Jones’s and Paige’s paths crossed again a short time later, this time as opponents during a new feature in the NNL2 schedule that exposed Black baseball players to a wider audience.13

In the 1930s and 1940s, Negro League franchises occasionally faced off in four-team doubleheaders at Yankee Stadium. These doubleheaders typically served as benefits for people or organizations and attracted crowds with both White and Black fans. A few weeks after the East-West Game, the NNL2 held the season’s first doubleheader at Yankee Stadium. Held to benefit Sergeant George W. Curley and John W. Duncan, it featured the American Giants and the Black Yankees in the first game and the Stars and Crawfords in the second.14 The Stars-Crawfords game, a 1-1 pitching duel between Jones and Paige, was called after nine innings because of darkness. Both pitchers completed similar performances. Paige allowed six hits and notched 12 strikeouts while Jones allowed three hits and struck out nine batters. The Tribune’s Ed Harris praised Paige and Jones and noted that the event attracted many White spectators. Harris also wrote that both games featured playing “fit for the big leagues” and that the high attendance disproved the notion “that Negro baseball isn’t worth a dime.”15 Three weeks later Paige and the Crawfords triumphed over Jones and the Stars in a rematch at another Yankee Stadium four-team doubleheader. The second doubleheader attracted another large crowd to Yankee Stadium, and the crowd cheered for Jones in the losing effort.16

Overall, Jones’s performance reflected the team’s performance throughout the 1934 season – they held their own against the top teams and top players in the NNL2. Jones led the Stars’ pitching staff with a 20-4 record and a 1.29 ERA. Webster McDonald, Rocky Ellis, and Lefty Holmes joined Jones in the starting rotation and all posted sub-3.00 ERAs. McDonald also served as the team’s field manager. Among the Stars’ offensive players, infielder Jud Wilson led the team with a .358 batting average and a .931 OPS. Outfielder Chaney White had the second-highest batting average on the team, .302, and an OPS of .760. Other top performers on the team included Jake Dunn, Jake Stevens, and Biz Mackey. The Stars finished with a league record of 39-18-10 and captured the second-half title of the NNL2 season. They faced the Chicago American Giants, winners of the first half, in a controversy-marred championship series that undermined the Stars’ achievements.17

The controversies in the championship series revolved around the actions of the umpires and of the NNL commissioner, Rollo Wilson. In Game Six, two Stars players, Jud Wilson and Ameal Brooks, physically attacked umpires in two separate incidents. Despite those outbursts, the umpires did not eject either Wilson or Brooks from the game. The Stars won Game Six, prompting American Giants manager Dave Malarcher to formally protest the game to the commissioner. Rollo Wilson considered suspending Jud Wilson and Brooks from Game Seven, the last scheduled game in the series. Both Bolden and Gottlieb met with Wilson prior to Game Seven and pressured Wilson to avoid suspending either player. Bolden added to the tense atmosphere and to the American Giants’ justified anger by threatening to pull the Stars from the series if Wilson suspended the two players. The threat worked, and Wilson both denied the American Giants’ protest of Game Six and permitted all players to participate in Game Seven.18

Due to the lack of any consequences for bad behavior in Game Six, the on-field disruptions continued for the rest of the series. Game Seven featured another player-led attack on an umpire. This time, the American Giants’ left fielder, Mule Suttles, protested a called third strike by hitting the umpire in the head with his bat. Unlike the previous game, the umpire promptly ejected Suttles, and a riot nearly erupted on the field. To compound those on-field problems, the game ended in a tie because it was played on a Sunday in Philadelphia and the state of Pennsylvania still enforced blue laws in 1934. Those laws put a 6:00 P.M. curfew on the game, and the on-field disruptions prevented the game from being completed by the curfew. The tie game resulted in a hastily scheduled Game Eight on Monday, a game that brought more protests from both the Stars and the American Giants. The American Giants disputed an umpire’s call at home plate. The Stars argued that the American Giants used a player who was under contract with another NNL2 franchise.19

Not surprisingly, coverage of the championship series spent little time praising the Stars and much time lamenting the sorry spectacles that played out over the series’ final games. Columnist Ed Harris asserted that Wilson’s and Brooks’ “illegal” and unfair” actions in Game Six set “[u]nhappy precedents” and fomented “out-and-out diamond lawlessness.”20 Harris further criticized Wilson and Brooks for forgetting “it was a championship game, that their services were valuable to the teams, [and] that spectators had paid to see a baseball game and not a court-room debate or a prize fight.”21 He both expressed sympathy for and criticized the umpires in Game Six. While acknowledging that umpires’ decisions almost always attract criticism, Harris chastised them for not ejecting Wilson and Brooks. According to Harris, their actions set “unfortunate precedents” and gave Malarcher ammunition for filing a protest with the league commissioner.22 Harris also correctly predicted that the controversy-filled resolution to the 1934 NNL2 season would spill over into plans for 1935. Robert Cole, the American Giants’ owner, refused to sign paychecks unless all NNL2 members showed up at a meeting scheduled for Pittsburgh. Only Greenlee and Cumberland Posey of the Homestead Grays showed up, leading Cole to act upon his threat. One of the unsigned paychecks belonged to the commissioner, and that led Wilson to allege publicly that Cole was engaged in spiteful behavior in retaliation for his rulings during the championship series.23

The messy 1934 NNL2 championship series closed a chapter in the Stars’ history, one marked with power and success. With the Stars’ triumph, Bolden earned the distinction of taking his second franchise to the pinnacle of its league. He built the new franchise from scratch by relying on key veterans he knew from his days with Hilldale and by finding key younger players with promising futures. Bolden furthermore flexed his power by relegating another franchise in Philadelphia to a secondary status within the NNL and, in collaboration with Gottlieb, by pressuring the commissioner to avoid suspending players for bad on-field conduct. After the 1934 season, the Stars never again reached the pinnacle of the Negro Leagues, and the franchise spent the much of remainder of the decade flirting with obscurity. The Stars and their fan base never truly savored their 1934 title, and the rest of the league quickly moved on from the controversy-plagued series.

During the remainder of the 1930s, four key events exemplified the fallout from the Stars’ 1934 victory and the obstacles that prevented the franchise from rebounding and contending for another title. The first of those events happened early in 1935 as NNL owners gathered in Philadelphia to plan for the coming season. Wilson lost his job as league commissioner to Ferdinand Q. Morton, a New York City civil service commissioner who had no experience in professional baseball. The press speculated that Morton likely earned his new job because of a shift in power within the NNL2 to New York City. For the 1935 season, the league said farewell to the Bacharach Giants and hello to three franchises based in New York City region, the New York Cubans, Brooklyn Eagles, and Newark Dodgers. The introduction of the Brooklyn Eagles brought Abe and Effa Manley into the NNL2. The Manleys combined the Dodgers and Eagles franchises and moved the new team to Newark; Effa was to emerge as one of the league’s most influential officials. Overall, the election of a new commissioner and the welcoming of three new franchises marked a new chapter for both the Stars and the rest of the NNL2. The league now had a foothold in the New York City market and a decreased presence in the Philadelphia region. Additionally, by selecting a new commissioner, the team owners also delivered a rebuke to Wilson and demonstrated a desire to move on quickly from the Stars’ victory.24

The second key event came later in the 1935 season, a frustrating season for Bolden and the Stars, when Bolden lashed out at his players and the NNL2’s overall management. While the Stars mounted a challenge for the second-half title, they also endured a prolonged losing streak during the first half of the season and missed out on a chance to defend their crown. In response to that losing streak, Bolden used the pages of the Philadelphia Independent to detail extensive roster overhaul through in-season trades. Those trades never materialized, but Bolden’s frustration with his players persisted. Bolden suspended Slim Jones and stripped him of his salary for his “failure to attain proper physical condition.”25 Two other pitchers, Paul Carter and Rocky Ellis, faced fines of $5.00 and $10.00 respectively for “absence from the club during working hours without permission.”26 Bolden’s disdain for his players ran so deep that he asked Greenlee, the NNL2’s president, to limit the number of Stars players on the East team at the annual East-West Game. Greenlee did not take that action, and seven Stars players appeared on the East’s roster. Those players included the suspended Slim Jones; Webster McDonald, the Stars’ manager, managed the East squad. Undeterred, Bolden maintained his tough posture against his players and again threatened a roster overhaul before the next season. Bolden also used a spokesperson to vent about the league’s management and the unfair position he saw for the Stars within the NNL2. Through the spokesperson, Bolden complained about the amount of money the Stars lost on their road trips while other teams made money playing in Philadelphia due to the presence of more semipro teams whose contests filled gaps in the teams’ league schedules. Ultimately, Bolden wanted the NNL2 to cover less territory, wanted to expose a small group of owners who controlled all league affairs at the Stars’ expense, and wanted Philadelphia to host the next East-West Game.27

Bolden’s frustrations with his fellow owners seeped into the next season and led to the third key event that characterized the Stars’ post-1934 existence – the confusion over the first-half winner and ultimate cancellation of the 1936 league championship series. Prior to the 1936 season, Greenlee needed to resign his position as the NNL2’s president, and Bolden won the election to replace him. Bolden balanced his role as the league’s president with his role in building the Stars’ roster, making good on his threats from the previous season to complete a roster overhaul. Through his efforts, the Stars’ 1936 roster featured new players like Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, Larry Brown, Roy Parnell, and Bill Yancey. The revamped Stars held their spring training exercises at a YMCA in southwest Philadelphia, near the site of their home ballpark at 44th and Parkside Avenue. On the eve of the 1936 season opener, Bolden invited reporters to the YMCA and used the opportunity to deliver a stern lecture to his players. Through his lecture, Bolden established his high expectations for the Stars’ players both on and off of the field and his determination to release under-producing players.28 For most of the first half of the season, the Stars fulfilled Bolden’s high expectations and appeared poised to clinch the first-half title. Officially, however, the NNL2 did not recognize a first-half champion because neither the Stars nor the Baltimore Elite Giants, the other team claiming the first-half title, had followed the league’s rules. Those rules required NNL2 teams to play each other at least five times in each half of the season, so both the Stars and the Elite Giants needed to play additional games before the league would recognize a first-half champion.29

In July the controversy deepened when the league’s secretary, John Clark, who was affiliated with the Pittsburgh Crawfords, published official standings that awarded the first-half title to the Elite Giants. Bolden correctly noted that those standings were incomplete since the two teams still needed to face each other in two games as mandated by the league’s rules. His reasonable, and correct, objections created fissures among the NNL2 owners as some sided with Bolden while others sided with Tom Wilson, the Elite Giants’ owner who also served as the NNL’s treasurer. Ultimately, the controversy proved to be moot. The Stars and Elite Giants played the two missing games later in the season, and the Elite Giants won both of them to officially capture the first-half title. The NNL, however, never officially crowned a champion since neither the Elite Giants nor the Crawfords, the second-half winners, played the championship series. Most of the players from both teams opted to participate in the annual Denver Post Tournament; rather than carry on a sham of the championship series, the NNL simply canceled it and left the championship vacant for the 1936 season.30

Two years later came the fourth and final key event that characterized the Stars’ post-1934 existence and their inability to win another title – the premature death of Slim Jones. According to a story that appeared in November 1938, Jones died in his hometown of Baltimore after suffering a bout of double pneumonia. Later information, however, indicated that Jones died from kidney failure and other ailments. Jones never lived up to the promise he showed in the Stars’ championship season when he held his own in pitching duels against future Hall of Famer Satchel Paige. He suffered injuries to his left shoulder, a career-interrupting or career-ending development for a left-handed pitcher. To cope with his injuries, Jones turned to alcohol, and his alcoholism likely contributed to his death and to the clashes he had with Bolden over his physical conditioning. Jones’s death served as a tragic and apt example of the precarious life many players experienced in the Negro Leagues. They lacked the support systems modern-day baseball players have to recover from injuries and to prolong their careers. Jones’ death, furthermore, also tragically and aptly captured how the Stars paid a heavy price for their lone championship and never returned to the vaunted place within the NNL2 that they occupied in the 1934 season.31

Those four key events – the change in NNL2 commissioner and admission of three New York City area franchises; Bolden lashing out against his fellow NNL owners; the messy resolution of the first-half winner in 1936; and Jones’ untimely death – came against a backdrop of continued problems for the NNL2. Teams in the league regularly failed to play all the games on their published schedules, and players habitually “jumped” their contracts for more lucrative deals with teams outside of the league and outside of the United States.32 While owners threatened to ban contract jumpers, they never followed through with those threats since the contract jumpers ranked among the top players in Black professional baseball. The NNL also faced a competitor when the Negro American League (NAL) was launched in 1937 with teams scattered across Midwestern and Southern cities. Starting in 1939, a more ominous challenge to the existence of both the NNL2 and the NAL appeared in the pages of the Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most prominent Black newspapers in the country. On those pages, Wendell Smith wrote a series of articles that investigated whether the “major leagues” would welcome Black players. Those articles foreshadowed the intensive effort by Smith and others to pressure National and American League franchises to sign Black players and to end the segregation era in professional baseball.33

For the Stars and the rest of the Negro Leagues, the possibility of Black players in the segregated “major leagues” seemed remote in the early 1940s. Both the NNL2 and the NAL suffered many of the same problems that had plagued them in the 1930s – financial instability, incomplete schedules, and internal divisions among team owners. Additionally, both the NNL2 and NAL owners faced the continued prospect of contract jumpers and, once the United States entered World War II, the loss of players to the armed forces. The Stars remained mired in the middle-to-lower tier of teams in the NNL2 and toiled in the shadows of top-tier Black teams like the Homestead Grays, Newark Eagles, and Kansas City Monarchs. Behind the scenes, Bolden used his connections with members of the Philadelphia community to generate interest in the Stars and to try to make the team a part of the city’s culture. Gottlieb maintained a prominent role in scheduling games, and he worked closely with Effa Manley on managing the NNL2’s finances.34

During the World War II era, the most interesting development for the Stars came in 1943 when they started using Shibe Park to stage some home contests. Since their inception, the Stars had used two small ballparks for their home games – Passon Field at 48th and Spruce Street and the PRR YMCA Park at 44th and Parkside Avenue. The latter field, dubbed “Bolden Bowl” by Black sportswriters, was owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad and sat near a roundhouse in West Philadelphia. Due to that location, the 44th and Parkside ballpark presented some challenging playing conditions. Smoke from passing trains caused some game delays, and fans had to navigate the accumulated soot and ashes that covered parts of the ballpark, including the screen behind home plate. Shibe Park offered much better amenities as well as the potential for larger crowds. Since both the Philadelphia Phillies and Philadelphia Athletics used Shibe Park for their home games, the Stars faced a limit on the number of games they could play at the larger and nicer ballpark. The use of Shibe Park became a double-edged sword for the Stars and portended a troubled future for the franchise, particularly as the effort to get Black players into the White major leagues gained momentum during the wartime years.35

World War II provided a boost to the effort started and sustained by Wendell Smith in the pages of the Pittsburgh Courier. America’s global fight against fascism resonated with civil-rights activists on the home front and led to a movement call the Double Victory campaign that promised victory over racism at home and abroad. In 1944, the death of longtime Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, who did not appear to favor integration, provided some hope that at least one franchise would soon sign Black players. Landis’s replacement, Albert “Happy” Chandler, expressed more openness toward integration, and New York City’s government got involved as a way to pressure the Yankees, Giants, and Dodgers to open their franchises to Black players. Meanwhile, Wendell Smith and other Black sportswriters intensified their own campaigns. Prior to the end of World War II, Smith arranged for tryouts involving several Negro League players and major-league franchises. More importantly, Smith indirectly introduced Jackie Robinson to Branch Rickey, the general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers who was secretly planning to sign Black players. Rickey threw his support behind a new Negro league, the United States League, as a way to send his scouts to review Black players and to hide his true intentions. Robinson and Rickey had their famous meeting in Brooklyn in August 1945, and the formal announcement of Robinson’s signing came in October 1945 shortly after the conclusion of the baseball season.36

Robinson’s signing with the Brooklyn Dodgers organization initiated the final and most challenging era for the Stars and the rest of the Negro Leagues. In 1946, as Robinson played for the Montreal Royals, the Negro Leagues benefited from the attention devoted to him. The Stars and other teams enjoyed large crowds at their games, and those large crowds generated bountiful gate receipts for the Negro League franchises; for example, a game featuring the Stars and the Homestead Grays at Shibe Park attracted over 10,000 fans. The Stars even flirted with a first-place finish in the NNL2, but they lost steam and again finished the season out of contention for the championship. In the midst of the good news, the Stars and other franchises faced some ominous signs about their future. Stories about Robinson and a few other Black players who had signed with White major-league franchises dominated sports pages in Black newspapers. Additionally, Rickey and other officials who signed Black players did not always honor those players’ contracts with Negro League teams and offered little to no compensation. The decline in attention combined with the lack of respect foretold a bad future for both the NNL2 and the NAL in spite of an otherwise successful 1946 season.37

While the Stars and other Black teams prepared for the 1947 season, the Brooklyn Dodgers selected Robinson’s contract, and all attention in the baseball world went to the rookie who finally broke the color barrier. A few months into the 1947 season, Larry Doby joined the Cleveland Indians, meaning that both the American League and the National League featured integrated teams. Stories about Robinson and Doby appeared prominently in the sports pages of Black newspapers. The Stars felt this problem acutely as the Philadelphia Tribune carried advertisements for the Dodgers’ games against the Phillies and for the Cleveland Indians’ games against the Athletics. Those advertisements crowded out stories about the Stars and led to attendance problems felt around both the NNL2 and NAL. At the end of the season, when the Brooklyn Dodgers secured a World Series berth, the Philadelphia Independent’s editorial board devoted a lengthy editorial to Robinson’s presence in the World Series. The editorial praised Robinson for establishing a good example for other Black players and compared him to previous African American leaders like Frederick Douglass, Mary McLeod Bethune, and W.E.B. Du Bois. The Stars and other Negro League teams received scant attention, a sign that the Black press and baseball had largely moved on from those teams.38

The 1948 season featured even more Black players in the NL and AL and brought the Negro Leagues to the brink of irrelevancy. Bolden tried to reverse his franchise’s fortunes by hiring Oscar Charleston to be the field manager and also attempted to restructure the roster with younger talent. That revamped roster, however, lacked its own home ballpark since the Stars lost use of the field at 44th and Parkside and had to use Shibe Park to stage home contests in Philadelphia. Shibe Park offered only limited opportunities for the Stars to stage home games since both the Phillies and Athletics used the ballpark on most days of the baseball season. The Stars’ problems represented a microcosm of the problems facing both the NNL2 and the NAL. Major-league officials rejected all attempts by the Negro Leagues for consideration as minor leagues, and Negro League games drew sparse crowds. The NNL2 and NAL staged a final World Series between the two circuits in which the Homestead Grays defeated the NAL’s Birmingham Black Barons to emerge as champions. Soon after the series ended, the Grays left the NNL2 and decided to operate as an independent franchise. The Manleys sold the Eagles franchise, and the new owners took the team to Houston for two years and New Orleans for one final season before ceasing operations. The New York Black Yankees disbanded; the NNL also disbanded, leaving remaining teams like the Stars with few options to continue operations.39

For the next four seasons, the Stars endured an odd existence that merely delayed the franchise’s inevitable dissolution. In 1949, they joined a revamped NAL, but league-organized play had effectively ceased with the end of the NNL. The Stars and other remaining teams had little to support themselves other than the shrinking gate receipts they collected from their games. Additionally, the Stars continued to lose players to the major-league franchises and to see other players jump their contracts to join teams in the Mexican League. Bolden tried to minimize the damage from those developments by not publicly speaking about the losses and trying to focus attention on the players who remained on the Stars’ roster. In September 1950 the Stars suffered their biggest loss when Bolden died at the age of 68. He suffered a stroke at his home in Darby; he died on September 27at Darby’s Mercy-Fitzgerald Hospital. Bolden’s wife, Nellie, had died in 1948; he was survived by their daughter, Hilda, the director of a medical health center in Washington, D.C., and his two brothers. His funeral at Darby’s Mount Union Zion Church attracted many prominent members of the Philadelphia community and testified to the respect Bolden had earned throughout his lifetime.40

After Bolden’s death, the Stars continued to operate under the guidance of Gottlieb and Charleston. Charleston served as the team’s field manager and took control over personnel decisions. He built rosters full of young players and emphasized the Stars as a stepping stone to careers in major-league organizations. Through Charleston’s scouting efforts, the Stars attracted many local high-school and sandlot players and, for the 1952 season, carried a youthful roster whose players averaged 21 years old. Those young players faced grueling schedules that kept them on the road for long periods of time; to compound those problems, the Stars posted losing records and financial losses. Due to schedule conflicts with the Phillies and Athletics, the Stars also gradually delayed their debuts at Shibe Park. From 1948 until 1950, the team held its opener at Shibe Park in May, but rain washed out the scheduled opener in May 1950, and the Stars did not play in Philadelphia until early July. In their 1951 Shibe Park debut, the Stars lost a doubleheader to the Indianapolis Clowns and attracted a woeful crowd of 3,000 fans; at the same time, the last-place Phillies and the Dodgers drew 85,000 fans to a three-game series. The Stars’ 1952 “home” season again did not begin until July, and they attracted a meager 4,000 fans to their home opener.41

With those conditions facing the Stars, and with few prospects for a rebound in future seasons, Gottlieb in March 1953 made the sudden, yet not unexpected, announcement of the franchise’s dissolution. A few weeks later, Gottlieb retracted his earlier announcement and said that he would look for a buyer for the franchise. When no buyers came forward, Gottlieb put the Stars out of business; he granted all players free-agent status and focused his attention toward his basketball team, the Philadelphia Warriors. The Stars had played their final game. Their passing came without any retrospectives or mournful articles in the Black newspapers.42

In their 20 years of existence, Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars reflected the highs and lows, as well as the triumphs and tribulations, common to teams in the Negro Leagues in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. Their lone championship season came with a string of controversies that revealed the ugly side of the Negro Leagues and that ultimately prevented them from joining the register of top teams in the NNL2. Similar to other Negro League teams, the Stars struggled to remain relevant after Jackie Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Stars were a product of a segregated sports world and no longer had a place once franchises like the Dodgers, Cleveland Indians, and others carried integrated team rosters. The Stars’ story, though, remains relevant since it offers a fascinating and at times frustrating window into the challenges facing Negro League teams as they navigated racism, economic deprivation, and a world war.

COURTNEY MICHELLE SMITH is a professor and chair of the history and political science department at Cabrini University in Radnor, Pennsylvania. She is a lifelong fan of the Philadelphia Phillies and the rest of Philadelphia’s sports teams. She is the author of Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia and Jackie Robinson: A Life in American History. Her work also appeared in From Shibe Park to Connie Mack Stadium: Great Games in Philadelphia’s Lost Ballpark and Sports in Philadelphia. Aside from baseball, her research interests include Philadelphia history, Pennsylvania history, and American political history. She spends her free time rooting for the Phillies, Eagles, Sixers, Flyers, and Union.

Notes

1 Dick Sun, “Lundy To Lead Phila. Nine In Diamond Loop; Mogules Meet Here and Map Out Campaign for 1933 Season,” Philadelphia Tribune, February 9, 1933.

2 “Philadelphia Stars, Greatest Defensive Club in the East,” Colored Baseball and Sports Monthly 1, no. 4 (October 1934): 18. Edward Bolden Papers, Box 186-1, Folder 21; Manuscript Division, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

3 Courtney Michelle Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2017), 68-74.

4 W. Rollo Wilson, “Sport Shots,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 25, 1933.

5 Randy Dixon, “Galaxy of Baseball Aces to Play for Ed Bolden’s Phila. Stars this Season,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 16, 1933.

6 Dixon, “Stars Subdue Crawfords on Wilson’s Blow,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 18, 1933.

7 “5 Game Series Between Stars and Bacharachs,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 22, 1933; “Boldenmen and Passons Under Arclights Fri,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 20, 1933; “Crawfords Drub Boldenmen Three Times to Even Series,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 17, 1933.

8 “Greenlee Cleared in Lottery Case,” Pittsburgh Courier, March 18, 1933; Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 68; Leslie Heaphy, The Negro Leagues 1869-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2003), 93.

9 Dixon, “Newspaperman Accepts Job as Baseball Commissioner; Sweeping Reforms Are Made,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 15, 1934; Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 76-78; “Baseball Owners Enroute to Philly Pow Wow,” Pittsburgh Courier, February 10, 1934.

10 Dixon, “Wide Representation as Baseball Moguls Launch Plans for a Real League,” Philadelphia Tribune, February 15, 1934; Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 76-78; Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 35-39.

11 “Stars Topple Newark 12-0 for Initial League Win,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 19, 1934.

12 There is contradictory information about Jones’s career before he joined the Stars. Part of the confusion lies in the name of the franchise that played in Baltimore in 1932 and 1933. According to historian Gary Ashwill, the owners of the Baltimore Black Sox Baseball Club Inc. sought an injunction to prevent Joe Cambria, the owner of the NNL2 club, from using the name “Black Sox.” Newspapers referred to the franchise as both the Baltimore Sox and Baltimore Black Sox. “Black Sox Not to Disband; Locals Will Have Strong Team Says Cambria,” Baltimore Afro-American, February 18, 1933; “Seek to Enjoin Team from Use of ‘Black Sox,’” Baltimore Afro-American, May 27, 1933; “Sound Second Call for Baseball Meet,” Baltimore Afro-American, January 27, 1934; “Jack Farrell Let Go Upon Larceny Count,” Baltimore Afro-American,July 14, 1934.

13 “Stars Down Passon,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 16, 1934; “25,000 See East Down West 1-0,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 30, 1934; Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 80-83; Jack Pace, “Slim Jones,” Colored Baseball and Sports Monthly, v1 n2 (October 1934) in Edward Bolden Papers Box 186-1 Folder 21; Manuscript Division Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University; “Slim Jones,” Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/player.php?playerID=jones01sli.; “Slim Jones,” Baseball Reference, https://www.baseball-reference.com/players/j/jonessl01.shtml; “1934 East-West Game,” Seamheads Negro Leagues Database, https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/year.php?yearID=1934&lgID=EWA.

14 Ed Harris, “Jones and Paige Duel to 1-1 Tie,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 13, 1934.

15 Harris, “Points and Errors,” Philadelphia Tribune, September 13, 1934.

16 Harris, “Paige Tops Jones Before 25,000,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 4, 1934.

17 “1934 Philadelphia Stars,” Seamheads Negro Leagues Database. https://www.seamheads.com/NegroLgs/team.php?yearID=1934&teamID=PS&LGOrd=1.

18 Ed Harris, “and Bright Stars,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 11, 1934.

19 Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 84-85.

20 Harris, “To Be or Not to Be,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 4, 1934.

21 “To Be or Not to Be.”

22 “To Be or Not to Be.”

23 Harris, “Second the Motion,” Philadelphia Tribune, November 15, 1934; see also December 20, 1934.

24 Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 87-90.

25 “Slim Jones Suspended, Two Others are Fined,” Philadelphia Independent, August 11, 1935.

26 “Slim Jones Suspended, Two Others are Fined.”

27 “Bolden Will Quit,” Philadelphia Tribune, August 29, 1935.

28 Dixon, “Stearns, Suttles, Brown Head Here, Stevens Jumps,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 5, 1936; “Stars Fail to Land Chicago Aces; Slim Jones Ailing,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 12, 1936; Dixon, “The Sports Bugle,” and “Bolden Faces Problem with Gaps in Infield,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 19, 1936; Dixon, “Bolden Cracks Whip as Campaign Nears,” Philadelphia Tribune, May 3, 1936; “Ed Bolden Will Actively Manage Stars in Title Dash; Cockrells Ready,” Philadelphia Tribune, March 26, 1936; Ed Harris, “Ed Bolden Expects to be Strong Contender in 1936 Nat’s Assn. Race,” Philadelphia Tribune, April 16, 1936.

29 “Local Fans Acclaim Phila. Stars’ Feat,” Philadelphia Independent, May 17, 1936; Dixon, “The Sports Bugle,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 14, 1936; Dick Sun, “Stars Lose League Lead; Drop Three in Row to Elites,” Philadelphia Tribune, June 28, 1936; “Stars-Elites Tied, League Title Decided This Week,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 5, 1936; “First Half Ends with Title Undecided,” and Dixon, “Sports Bugle,” Philadelphia Tribune, July 12, 1936.

30 Ed Bolden, “Bolden Says League Secretary Guilty of Misusing Office,” Philadelphia Tribune August 23, 1936. Bolden, “Bolden Gives Views on 1st Half Title,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 22, 1936; Cumberland Posey, “Posey’s Points,” Pittsburgh Courier, July 25, 1936; August 1, 1936, and August 29, 1936; Harris, “Empty Barrels,” Philadelphia Tribune, October 8, 1936; “Elites Okay Title Frays,” Philadelphia Independent, September 6, 1936; Dixon, “Loyal Roots Go Broke When Greenlee’s Serfs Form Link with Gamblers,” Philadelphia Independent, September 13, 1936; Dixon, “Craws-Elites Give Fans Bum’s Rush,” Philadelphia Independent, October 4, 1936.

31 “‘Stars’ Southpaw Dies in Baltimore,” Philadelphia Tribune, November 27, 1938; Frederick C. Bush, “Stewart Jones,” Society for American Baseball Research Biography Project, Accessed January 17, 2023, https://sabr.org/bioproj/person/slim-jones/.

32 In the Negro Leagues, rainouts often resulted in canceled games because the venue would no longer be available to the teams. Additionally, owners who wanted the extra revenue of postseason games would intervene to make league games exhibition games in order to ensure postseason berths.

33 Wendell Smith, “Brooklyn Dodgers Admit Negro Players Rate Place in Majors” Pittsburgh Courier, August 5, 1939; Wendell Smith, “Would Be a Mad Scramble for Negro Players if Okayed,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 12, 1939; Wendell Smith, “Owners Will Admit Negro Players if Fans Demand Them – Cards’ Pilot,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 19, 1939; Wendell Smith, “Owners Must Solve Color Problem in Majors – Stengel,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 26, 1939.

34 Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 109-119.

35 Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 130-132.

36 Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 134-137.

37 Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 139-144.

38 “R. Partlow Rejoins Phila. Stars in Ala.,” Philadelphia Independent, April 26, 1947; “Phila. Stars Tripped by Elites in Opener,” Philadelphia Independent, May 10, 1947; “Dodgers’ Manager Bert Shotten Says … Jackie Robinson Will Make Grade in Majors,” Philadelphia Independent, May 31, 1947; “Cleveland Indians Buy Larry Doby from Eagles,” Philadelphia Independent, July 12, 1947; “Jackie Robinson in the World Series,” Philadelphia Independent, October 4, 1947.

39 Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 144-148.

40 W. Rollo Wilson, “Through the Eyes of W. Rollo Wilson”; “Notables to Attend Rites for Bolden,” Edward Bolden Papers Box 186-1 Folder 1; Manuscript Division, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University; Funeral Program for Ed Bolden, Edward Bolden Papers Box 186-1 Folder 1; Manuscript Division, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University; Western Union telegram, George B. Stevenson to Doctor Hilda Bolden, September 30, 1950; Condolences from Harriet Wright Lemon to Hilda Bolden; Condolence from Russell F. Minton, M.D., to Hilda Bolden; Western Union telegram, Dr. J.B. Martins, President of the NAL, to Hilda Bolden, October 2, 1950; Western Union telegram, Ambassador & Mrs. King, Liberian Embassy, to Hilda Bolden; Western Union telegram, Memphis Red Sox to Family of Edward Bolden, October 2, 1950; Western Union telegram Wayne L. Hopking to Hilda Bolden, October 2, 1950, Edward Bolden Papers Box 186-1 Folder 1; Manuscript Division, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University.

41 Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 148-152.

42 Smith, Ed Bolden and Black Baseball in Philadelphia, 154-156.