Ernest Hemingway and the Black Sox Trial

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the December 2020 edition of the SABR Black Sox Scandal Committee Newsletter.

“Cook County what crimes are committed in thy name” — Ernest Hemingway, letter to a friend, August 1921

“Cook County what crimes are committed in thy name” — Ernest Hemingway, letter to a friend, August 1921

Things were looking good for aspiring author Ernest Hemingway in the summer of 1921. He had recently become engaged and on July 21 — his twenty-second birthday — he wrote excitedly to his close friend Grace Quinlan to gush about his future wife.

“Suppose you want to hear all about Hadley,” he wrote. He explained that his fiancé, Hadley Richardson, was a great tennis player and the “best pianist I ever heard.” He felt she was, all in all, “a sort of terribly fine article.” Married to her, he believed he would no longer experience that loneliness “that’s with you even when you’re in a crowd of people that are fond of you.”1

Hadley had already tried on her wedding dress. From her home in St. Louis, she wrote Hemingway that it made her look like “a human hazelnut tart.”2 Although Hemingway was still having trouble selling his fiction, he had found a job as a magazine writer, and he was looking forward to his wedding in the fall.

At the same time, Hemingway was also living through circumstances painful to him as someone who had grown up as a fan of the Chicago White Sox. While Hemingway was going to his job in the Loop District of downtown Chicago, seven members of the White Sox were on trial in the nearby Cook County Criminal Court Building, accused of having colluded with gamblers to throw the 1919 World Series.

Missing him, Hadley made arrangements to visit Hemingway in Chicago at the beginning of August. She arrived in a city alive with tension. It must have felt something like the moment when a high-wire artist wobbles slightly on the narrow line stretched taut high above and you feel that sudden sharp twinge of fear.

Chicago’s residents must have carried a similar disquiet within them as they wondered how things would turn out for Shoeless Joe Jackson and the other accused White Sox players. When Hadley arrived in Chicago on August 1, the White Sox criminal trial was nearing its conclusion. The Chicago Tribune announced: “Defense Pleas of ‘Black Sox’ to Start Today” and “Case Expected to Reach Jury Wednesday.”3

Such events always seem to mark us, the watchers, more profoundly than we expect — a situation I suspect holds especially true during the idealistic days of our youth. Because although we are not directly involved, we have seen these athletes run. We have seen what it means for a mere mortal to transform into something fluid and beautiful on a playing field. Perhaps this is why it is especially when sports heroes are accused of doing something dreadful that we instinctively register this as something momentous, as if a Greek myth were being enacted before our eyes.

What was going to happen? That was the question on everybody’s lips. It makes sense to believe that just like everyone else in Chicago that week, Hadley and Hemingway discussed this subject together. The Cook County Criminal Court Building, at 54 West Hubbard Street just north of the Chicago River, sat not far from Hemingway’s place of employment at 128 North Wells Street, so he may even have taken Hadley, as a visitor to the city, to wander past the building’s imposing neo-classical structure and wonder about what was transpiring inside.

On Tuesday, August 2, the Tribune confirmed that the Black Sox jurors would “retire to deliberate sometime after 5 o’clock this afternoon.”4 Their deliberations did not take long. The next day a huge headline in thick block letters on the front page of the Tribune declared, “JURY FREES BASEBALL MEN.”5 The accused Chicago players were acquitted on a single ballot. The Black Sox wouldn’t go to jail.

Hemingway was disgusted. After he read the news, he wrote to his good friend Bill Smith Jr. to express his anger at how things had played out. This was a team he had loved,6 and they had returned his trust by conspiring with gamblers — charges made against them during the trial that Hemingway’s letter makes it clear he believed.

Most of his letter to his friend Bill concerns personal affairs. He devotes relatively little space to discussing the results of the White Sox criminal trial but what he does say makes it clear Hemingway was incredulous that the White Sox had been acquitted in spite of the confessions made by Shoeless Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, and Lefty Williams before a grand jury 11 months earlier and in the face of the strong trial testimony against them made by gambler Bill Burns and his “sidekick,” Billy Maharg.7 Hemingway rhetorically asks himself in his letter to his friend if something as astounding as this ruling could have happened anywhere else: “Cook County what crimes are committed in thy name”8

Hemingway followed the Black Sox trial closely enough to have intuited a theory that researcher Bill Lamb has also expressed about this trial’s results. As Lamb explained in a 2016 article for SABR’s Baseball Research Journal, the “extraordinary exhibition of camaraderie” between jury members and the indicted White Sox immediately after the trial “suggests that the verdict may have been a product of that courthouse phenomenon that all prosecutors dread: jury nullification.”

Lamb observed that “in a criminal case, jurors are carefully instructed to abjure passion, prejudice, sympathy, and other emotion in rendering judgment.” In some instances, though, this injunction can fail. In the case of the Black Sox trial, it appeared to Lamb that the defense counsel “worked assiduously to cultivate a bond between the working-class men on the jury and the blue-collar defendants.”9

Hemingway would almost certainly have read in the Chicago Tribune’s coverage of the trial’s outcome on August 3 that following the trial’s verdict “the courtroom was like a love feast as the jurors, lawyers, and defendants clapped each other on the back and exchanged congratulations.”10 From this, Hemingway appears to have arrived at the conclusion that the jury identifying with the ball players had been a key factor in the acquittal.

To his friend Bill Smith, Hemingway exclaimed in his letter, “My Gawd Justice has about as much of a petition here as the Madame would have being tried for the murder of Lyle Shanahan before a picked Venire of Local Boys.”11

According to Hemingway scholars Sandra Spanier and Robert Trogdon, “Madame” was Hemingway’s way of referring to Bill Smith’s aunt, and Shanahan was a “broad-minded citizen of sterling worth” who lived, as did Smith’s aunt, in Michigan. Hemingway’s analogy for the White Sox trial suggested that if Bill Smith’s aunt had murdered a highly respected member of her community she could expect to be let off, as the White Sox had been, as long as the jury consisted of local cronies.”12

On August 6, their last day together in the city before she had to head for home, Hadley and Hemingway ate lunch at a German restaurant. In a letter Hadley wrote Hemingway after arriving in St. Louis, she told him how she felt during that final meal together: “I could’ve kissed you so hard,” she wrote, “so easily, at any moment.”13 Despite the baseball crisis that had been going on around them during her stay, it had been a wonderful visit.

In retrospect, the gloomy historical context for their warm prenuptial meeting seems somewhat fitting. It was only a few years into their marriage when Hemingway began having an affair with the woman who would become his second wife. Against the hopes and dreams nurtured during that precious week they had spent in Chicago, against the backdrop of the Black Sox trial, lurked the dark truth the trial had underscored: love can be rewarded by betrayal at any time.

Ernest Hemingway letter to William B. Smith Jr. [c. 3-5 Aug. 1921]

“You probably by now have viewed a peper [sic, joke spelling of newspaper] telling of the Hose aquital [sic]. Cook County what crimes are committed in thy name. Where else could it have been done? New York probably. You recall the Abe Attell angle? Acquitted in the face of Burns and Maharg’s testimony and their own confessions! My Gawd Justice has about as much of a petition here as the Madame would have being tried for the murder of Lyle Shanahan before a picked Venire of Local Boys.”

Photo credit

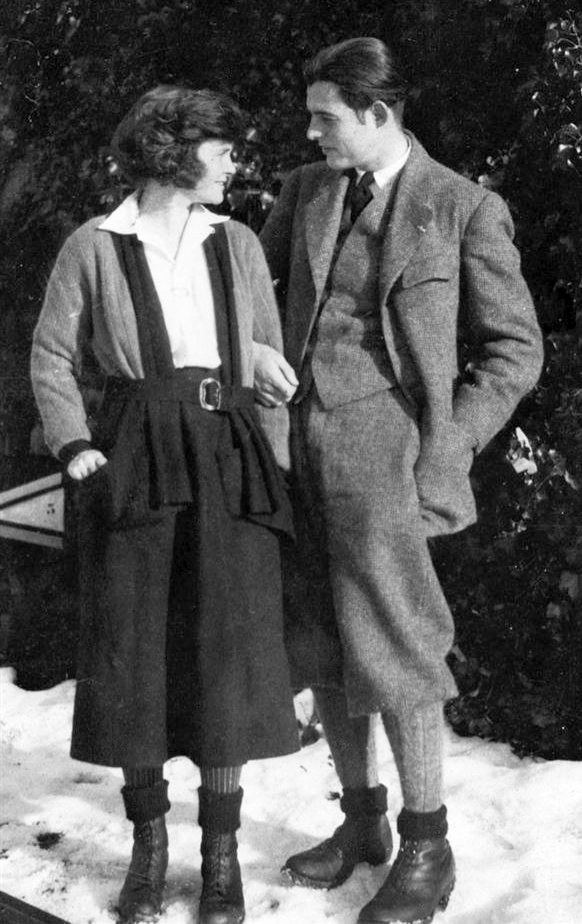

Ernest and Hadley Hemingway are pictured in Chamby, Switzerland, in 1922. (Photo: John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum)

Notes

1 Ernest Hemingway letter to Grace Quinlan, July 21, 1921 in The Letters of Ernest Hemingway 1907-1922. Vol. 1; eds. Sandra Spanier and Robert W. Trogdon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), 289-90.

2 Hadley Richardson letter to Ernest Hemingway, July 16, 1921, qtd. in Gioia Diliberto, Paris Without End: The True Story of Hemingway’s First Wife (Harper Perennial, 2011), ebook.

3 “Defense Pleas of ‘Black Sox’ to Start Today,” Chicago Tribune, August 1, 1921: 12.

4 “‘Black Sox’ Case to Be Given Jury Sometime Today,” Chicago Tribune, August 2, 1921: 10.

5 “Jury Frees Baseball Men,” Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1921: 1.

6 For more on Hemingway’s belief in the Chicago White Sox and his personal reaction to the September 1920 White Sox confessions, see Sharon Hamilton, “Hemingway Gambles, Loses on 1919 White Sox,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Committee Newsletter, June 2020: 12-13.

7 Bill Lamb, “The Black Sox Scandal,” https://sabr.org/journal/article/the-black-sox-scandal/. Accessed December 1, 2020.

8 Ernest Hemingway to William B. Smith Jr. [c. Aug. 3-5, 1921] in Letters, Vol. 1, 293-94.

9 Lamb, “The Black Sox Scandal.” For more on the White Sox trial and jury nullification, see Bill Lamb, “Jury Nullification and the Not Guilty Verdicts in the Black Sox Case,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Spring 2016, https://sabr.org/journal/article/jury-nullification-and-the-not-guilty-verdicts-in-the-black-sox-case. Accessed December 1, 2020.

10 “Jury Frees Baseball Men,” Chicago Tribune, August 3, 1921: 1. For more on the post trial celebrations and the intimacy of the jurors and the players they acquitted, see Jacob Pomrenke, “Diamond Joe and the Black Sox jury celebration,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Committee Newsletter, December 2017, https://jacobpomrenke.com/black-sox/diamond-joe-esposito-1921-jury-celebration. Accessed December 1, 2020.

11 Ernest Hemingway to William B. Smith Jr. [c. Aug., 3-5, 1921] in Letters, Vol. 1, 293-94.

12 Ernest Hemingway to William B. Smith Jr. [c. Aug., 3-5 1921] in Letters, Vol. 1, 294, and footnote 2 in Letters, Vol. 1, 297.

13 Hadley Richardson letter to Ernest Hemingway August 10, 1921, qtd. in Gioia Diliberto, Paris Without End: The True Story of Hemingway’s First Wife (Harper Perennial, 2011), ebook.