Fixers from the Steel City: The Black Sox Scandal’s Pittsburgh Connection

This article was published in the June 2015 issue of the SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee newsletter.

On September 28, 1920, Cook County Assistant State’s Attorney Hartley Replogle announced, “We are going after the gamblers now. There will be indictments in a few days against men in Philadelphia, Indianapolis, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, and other cities.”

The principals of the Philadelphia (Billy Maharg), Indianapolis (the Levi brothers), and Cincinnati (Phil Hahn, Fred Mowbray) gambling rings are easily identified, as they were eventually investigated and/or indicted by the grand jury. But the Pittsburgh connection, so much the focus in the early days of the Black Sox investigation, seemingly petered out. There was a lot of Pittsburgh smoke visible in 1919 and 1920. This article will examine what fire produced that smoke — and why no indictments resulted.

Early reports of the fix pointed to gamblers in Pittsburgh being as responsible as those of any other city. Only one month after the 1919 World Series ended, the racing tabloid Collyer’s Eye alleged that St. Louis, New York, Chicago and Pittsburgh gamblers had cleaned up $500,000 on the Series.1 Collyer’s had already charged that the Series was fixed, and clearly implied that gamblers in these four cities participated in on the fix.

The St. Louis (Carl Zork), New York (Abe Attell, Arnold Rothstein) and Chicago (the players) angles have been exhaustively examined, by baseball officials at the time, and by historians ever since. But not the Pittsburgh angle. This may in part be due to the decidedly non-curious attitude of the Pittsburgh media. Pittsburgh newspaper reporting on the 1919 Series emphasized that most local wagering favored the White Sox, up to the opening of the Series, when the betting suddenly swung toward the Reds. The (pollyannaish) Pittsburgh Gazette-Times attributed this “strange thing”, this sudden surge of Cincinnati betting, to “spirit” and National League solidarity.2

Immediately after the Series, the city’s leading sports columnist, Harry Keck of the Gazette-Times, dismissed the notion of a fix:

There has been a lot of loose talk throughout the series, mainly among those who bet and lost on the Sox, to the effect that Eddie Cicotte, the star pitcher of the Sox, had been “fixed’”by a gambling syndicate to throw games, and even that the series in its entirety had been cooked up. … Clear-thinking people will give little credence to these rumors.3

With this head-in-the-sand attitude, common for the non-Pittsburgh press as well, investigations were unlikely.

World Series fixer Abe Attell’s connection to Pittsburgh helped local gamblers reportedly win hundreds of thousands of dollars in bets against the Chicago White Sox during the 1919 World Series (Chicago History Museum)

The most credible, detailed story of Pittsburgh’s involvement appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on September 26, 1920. Datelined Pittsburgh, it claimed that local gamblers admitted to winning “several hundred thousand dollars” on the series. The gamblers wouldn’t give their names, fearing they would be subpoenaed by the grand jury if they did.

The gamblers said that Abe Attell had placed the bribe money with Chick Gandil. They claimed that Chick Gandil, Happy Felsch, Lefty Williams, and Eddie Cicotte, four players known now as guilty, had been fixed. The gamblers held off on betting each game until they got the green light from Attell. The ebb and flow of the betting, especially the plunging whenever Cicotte pitched, made it evident to all that “something crooked” was going on.

While no names were given in the story, the story gave details clearly referring to actual people. “One prominent gambler,” who was broke a week prior to the Series, suddenly appeared two days prior to the Series with a $25,000 certified check, which he bet on the Reds. He cleaned up $60,000. A “prominent 5th Avenue gambler” noted that Attell was well known in Pittsburgh. He noted that the ex-manager of Monte Attell, Abe’s boxing brother, owned a café in Pittsburgh, and was said to be “well-known in sporting [gambling] circles.”4

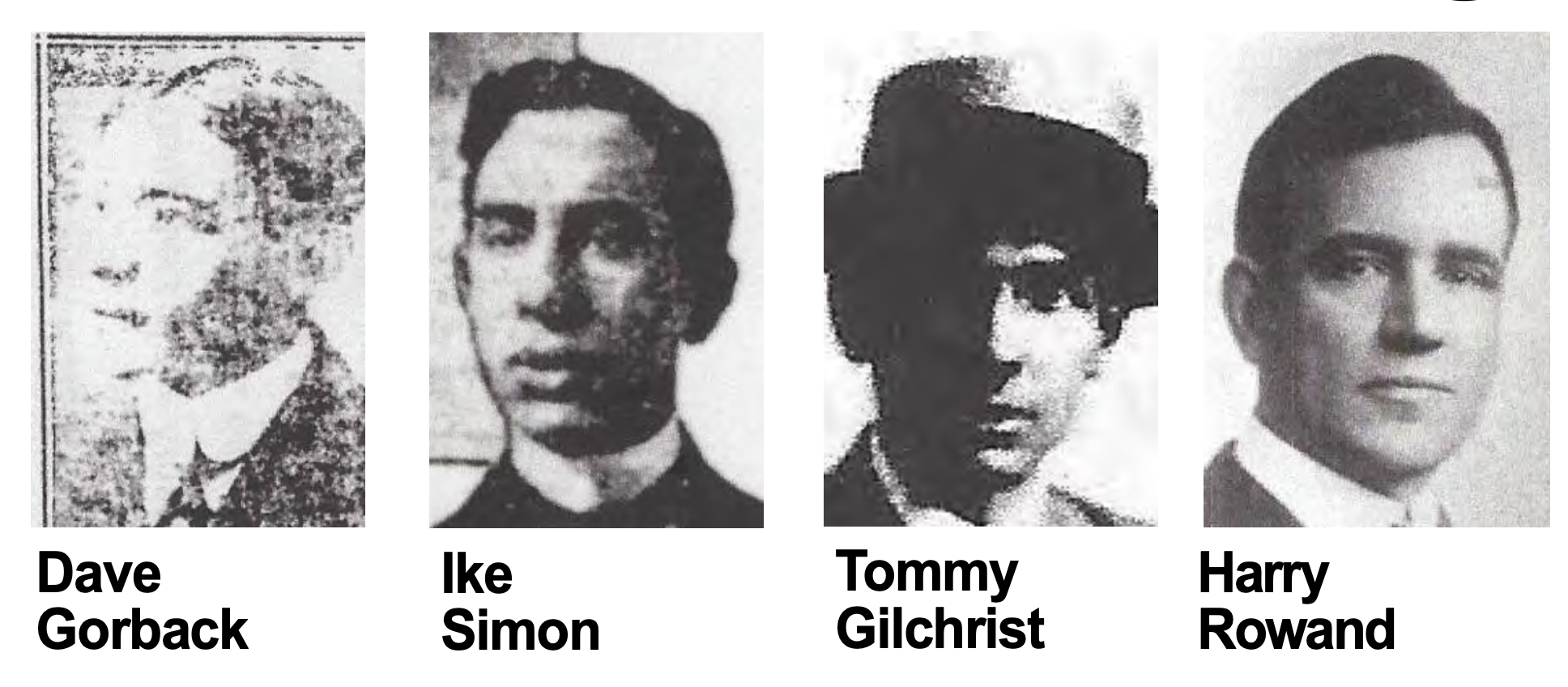

It seems probable that Abe Attell worked through trusted buddies in Pittsburgh. The café owner and ex-manager named in the Inquirer article can be identified as David L. Gorback, a café and hotel owner whose café had been closed due to gambling. Another local with strong connections to the Attells was Isaac “Ike” Simon. Former city councilman and gambler Simon ran the National Athletic Club, and had promoted several of Abe and Monte Attell’s fights.

While there is no direct evidence Gorback and Simon were Attell’s Pittsburgh “point men” for the city’s gambling community, they are the two most likely candidates.5

The “Pittsburgh connection” had surfaced several days prior to the Inquirer article. On September 23, 1920, New York Giants pitcher Rube Benton testified to the Black Sox grand jury that his close friend, Cincinnati “betting commissioner” Phil Hahn, told him the World Series had been fixed.

He said that the deal to fix players to throw the series had been engineered by a syndicate of gamblers from Pittsburgh, for whom he worked in Cincinnati as betting commissioner.

He said certain players on the White Sox had visited Pittsburgh before the series was played and made arrangements to throw the games for a price. He said that the players demanded $100,000 …

According to Benton, Hahn named four of the players — Eddie Cicotte, Claude Williams, Chick Gandil and Happy Felsch — the same four as the Pittsburgh gambler identified. Benton added that he was “sure” Eddie Cicotte could name the head of this Pittsburgh syndicate.6

Benton’s information included the exact amount ($100,000) and the names of four of the known Black Soxers. It is clear he had accurate “insider” information. Thus, his mention of Pittsburgh must be given credence.

Although Phil Hahn vociferously denied Benton’s charges, Hahn made an obvious candidate for arranging a Cincinnati-Pittsburgh fix. He was a former minor-league ballplayer, a close friend of Benton and other major leaguers, a known bookmaker. A Pittsburgh native, he had close ties to the gambling community there.7

However, Benton’s testimony was, at best, secondhand — and from a source of doubtful credibility. None of the fix leaders ever mentioned a visit to Pittsburgh, and there’s no other evidence that any Pittsburgh gambler wagered — or even possessed — the “hundred thousand dollars” needed to pull off such a fix. The suggestion is that Benton (or Hahn, or both) conflated the actual New York fix deal, with Pittsburgh gamblers participating in this New York-based fix.

Benton’s testimony ignited a nationwide firestorm. For several days — until the Billy Maharg revelations about Arnold Rothstein — the focus was as much on Pittsburgh gamblers as it was on New York gamblers. And that focus made some sense, to those “in the know.”

Pittsburgh “enjoyed” a nationwide reputation as a center of baseball bookmaking, with the local police and courts looking the other way. In 1921 the Methodist Church declared the Steel City “the greatest center of baseball pool gambling in the United States.” That same year, just prior to the Black Sox trial, baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis flayed the Pittsburgh police and courts for not enforcing the laws on baseball gambling. Famed sportswriter (and Black Sox exposer) Hugh Fullerton called Pittsburgh “a hotbed of gamblers … which goes almost unmolested.” The biographers of Hal Chase asserted that “rumors all season [1919] pointed to a Pittsburgh syndicate … as being the main engine for almost daily corruption in both leagues.”8

Eddie Cicotte’s grand jury confession verified this Pittsburgh connection. According to the New York Tribune of September 29, 1920, Cicotte testified that in early talks about the fix, “Abe Attell and three Pittsburgh gamblers agreed to back [Gandil].”9 Sleepy Bill Burns’ corroborated Cicotte’s testimony at the Black Sox trial. Burns related how, in the Sinton Hotel the day of the Game Two, in a meeting with Attell, Bennett, and Maharg, “someone said Pittsburgh gamblers were in on the deal …” and that those gamblers were having “a hard time getting the money down.”10

Chicago businessman Harry Long, who had placed bets for Sport Sullivan, further corroborated the Pittsburgh connection, telling the Chicago Tribune that during their dealings Sullivan had made phone calls to “Pittsburgh, Boston, New York, and Cincinnati.”11

Picking up the news from Chicago, Allegheny County (Pittsburgh) District Attorney Harry H. Rowand vowed to call a grand jury in that city if evidence was developed by the Chicago grand jury. “If there is any evidence that Pittsburgh gamblers were implicated in the plot to have the games thrown … I will leave no stone unturned in having the guilty parties brought to justice.” As in other cities, these stirring vows never resulted in any indictments.12

A later report out of Pittsburgh suggested a lesser role in the fix. The New York Times, on September 30, 1920, published an interview with a “prominent gambler” from Pittsburgh, who claimed:

The first intimation that we had last year that there was any suspicion in regard to the games between the White Sox and the Reds was a visit here of two Philadelphia men, one by the name of Gilchrist, I believe, who placed bets amounting to $5,000 for the first two games, taking Cincinnati for their end. As the White Sox at that time were the favorites in the betting this aroused suspicion here, and a great many of the betting fraternity placed their money the same way, and of course won out handsomely. However, I am sure that no one here did any fixing of players or knew anything about it.3

Much of this story can be verified. There was a Philadelphia gambler named Gilchrist, who is known to have backed the Reds. Dr. Thomas “English Tommy” Gilchrist worked in the Philadelphia city coroner’s office by day. But at night he bossed many of that city’s casinos. He was a known associate of Arnold Rothstein, and was, according to the Philadelphia newspapers, one of only two gamblers in that city who bet on the Reds.14

Obviously, the quoted “gambler” might have denied knowledge of the fix because he wanted to cover up his knowledge of the fix. Alternatively, he wasn’t a member of the Pittsburgh fix ring.

Yet another Pittsburgh fix candidate surfaced in Harry Redman’s October 26, 1920 grand jury testimony. Redman claimed that after Game Three, he and other gamblers tried to raise a fund to re-bribe the Black Sox, and that one of the gamblers they approached was “Stacey from Pittsburgh” (who declined).15

It is unclear whether the gambler declined due to honesty, or — more probable, as Redman thought “Stacey” corrupt enough to join in — because he was already in on the fix and made his profit. The grand jury never explored the identity of this “Stacey;” understandably, as “Stacey” had turned Redman down.16

The Pittsburgh newspapers never pursued this local angle.

Conclusion

There is no credible evidence that Pittsburgh gamblers instigated the fix, or that they had the resources to instigate such a fix. But there is credible evidence, via the Philadelphia Inquirer article, that Pittsburgh gamblers joined in on the fix.

As the indicted St. Louis gamblers Carl Zork and Ben Franklin did, they heard a tip about a “sure thing,” and jumped on it. The Rube Benton testimony reflects a garbled version of this reality. Unlike Carl Zork, the Pittsburgh gamblers were smart enough (or sober enough) not to have bragged about the fix in public. The fix proved so widespread, involving gamblers in Boston, New York, Des Moines, Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans, St. Louis, and Philadelphia (among other places), as to overwhelm the resources of the Cook County prosecutors. In that context, and in the absence of better evidence, it’s easy to see why the prosecutors never actively pursued the Pittsburgh angle.

Photo credits

Dave Gorback: Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, August 1, 1923. Ike Simon: Pittsburgh Press, January 21, 1909. Tommy Gilchrist: 1919 U.S. Passport application. Harry Rowand: The Book of Prominent Pennsylvanians (1913), p. 94.

Notes

1 Collyer’s Eye, November 15, 1919 (emphasis added).

2 Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, October 2, 1919. The day before, the Gazette-Times ran a wire service article on how the national odds had suddenly shifted from the Sox to the Reds. It attributed the shift to rumors about the health of Eddie Cicotte’s arm.

3 Pittsburgh Gazette-Times, October 10, 1919. This is one of the first times (if not THE first time) Cicotte’s name was mentioned in a newspaper article as a possible fixer.

4 Philadelphia Inquirer, September 26, 1920. “5th Avenue” was Pittsburgh’s swankiest street to live on.

5 For Gorback, see: Pittsburgh Gazette Times, July 5, 1919, August 1, 1923; Jewish Criterion, August 3, 1923; Pennsylvania Death Certificate. For Simon, see: Pittsburgh Press, January 21, 1909, May 27, 1912, July 26, 1914; Denver Post, January 25, 1912; Duluth News-Tribune, February 25, 1912; Pittsburgh Gazette Times, March 4, 1912, July 5, 1919; Jewish Criterion, October 16, 1942; World War I draft registration; Pennsylvania Death Certificate. In 1921 Simon was arrested for bribing Prohibition agents.

6 Altoona Mirror, September 24, 1920; Kansas City Star, September 24, 1920.

7 For Hahn, see my article in the December 2014 Black Sox Research Committee Newsletter.

8 Richmond Times Dispatch, June 12, 1921. Duluth News-Tribune, June 21, 1921. Chicago Eagle, August 25, 1917. Dewey and Acocella, The Black Prince of Baseball, cited in Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington, D.C., Potomac Books, 2006), 238. Art Rooney, owner of the Pittsburgh Steelers, co-owned a Pittsburgh casino in the late 1920s. Biographies of Rooney (cf. Arthur J. Rooney, Ruanaidh: The Story of Art Rooney and His Clan (2008)) contain a rich overview of the widespread gambling in that city, and the public’s acceptance of that gambling.

9 New York Tribune, September 29, 1920.

10 Miami News, July 9, 1921.

11 Chicago Tribune, October 22, 1920 (emphasis added). Sullivan’s contacts in New York, Boston, and Cincinnati are well known.

12 Washington Evening Star, September 26, 1920.

13 New York Times, September 30, 1920.

14 For Gilchrist, who was later jailed for narcotics peddling, see the Philadelphia Inquirer, December 31, 1916; New York Times, December 29, 1928; Brooklyn Standard Union, July 6, 1931; Harrisburg Telegraph, September 4, 1930: World War I Draft Registration; 1919 Passport Application. The Philadelphia Inquirer, October 1, 1920 reported that Gilchrist and “Red” McGoldrick were the only two prominent Philadelphia sportsmen to wager on the Reds. Gilchrist claimed that he bet the Reds “on form.” The article also notes that agents of Attell and Sullivan mulcted local Philadelphia bettors of $60,000. One prominent Philadelphia gambler, pool hall owner Charles Mosconi, heard the fix rumors and passed that information along to White Sox manager Kid Gleason. An aside: Mosconi (1868-1942) was the uncle of billiards legend Willie Mosconi.

15 Redman testimony, Chicago History Museum Black Sox collection, Box 2.

16 This author thinks there was a transcript error here, and that the gambler referred to might be John A. Staley (1861-1928), a well-known Pittsburgh drug firm owner and high-roller “sportsman.” Alternately, this “Stacey” might be of Cincinnati family of company owner James E. Stacey (1856-1931).