Judging the Jurist: Hugo Friend and the Black Sox Trial

This article was originally published in the December 2024 edition of the SABR Black Sox Scandal Committee Newsletter.

Judge Hugo M. Friend presided over the Black Sox trial during the summer of 1921, less than a year after he was tabbed to fill a temporary vacancy on the Cook County circuit court bench. (Photo: Chicago History Museum, Chicago Daily News Collection, DN-0073350)

In January 1921, 15 sitting judges were transferred to Chicago’s criminal courts to handle the multitude of defendants awaiting trial on serious felony charges. Although murder cases and other locally notorious matters were on the docket, only one matter commanded nationwide attention: the conspiracy and fraud charges leveled against those accused of fixing the 1919 World Series. Designating the jurist who would preside over the Black Sox proceedings was the responsibility of presiding criminal court Judge Charles A. McDonald, the magistrate who had superintended the grand jury presentation of the case.

From the expanded roster of judges available to him, McDonald selected Circuit Court Judge Hugo M. Friend. On its face, the choice seemed an odd one for such a high-profile case, as Friend was among the least seasoned members of Chicago’s criminal bench. He had only been appointed to the judiciary the previous fall1 and his criminal trial experience was limited to presiding over about a half-dozen cases. But that thin resume included three capital murder cases (as the Windy City had no shortage of accused killers)2 and the judicial novice had quickly demonstrated his capabilities.3

The trial of the Black Sox defendants, conducted before Judge Friend and a jury during the summer of 1921, ended with the acquittal of the accused. As expressed in previous writings, this author holds the view that the prosecution presented an overwhelming and unrefuted case against player defendants Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams, and a strong, if more circumstantial, one against Chick Gandil, Swede Risberg, and gambler David Zelcer, and that their exoneration was a product of jury misfeasance.4

This essay analyzes rulings rendered during the proceedings by Judge Friend and comments upon their effect on the trial’s outcome.

The spotlight will be trained on five specific issues dealt with by the court. Analysis, regrettably, is handicapped by the unavailability of the complete Black Sox trial transcript, of which only snippets survive today. Reliance must therefore be placed on sketchy newspaper accounts of the courtroom proceedings. To perhaps compensate readers for that shortcoming, the exposition here will forego legal jargon and case law citation, and present its arguments in everyday English. Preceding the forensics is a brief look at Judge Friend’s background.

Before the Black Sox Trial

Hugo Morris Friend was born on July 21, 1882 in Prague, then a Bohemian outpost of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, now the capital of the Czech Republic. When Hugo was a toddler, the Friend (originally Freund5) family emigrated to America, settling in Kansas before relocating to Chicago in 1890.

During his days at South Division High School and thereafter the University of Chicago, Friend was an athletic standout, particularly in track and field.6 In 1904, he set a Western (now Big Ten) Conference record in the long jump (22 feet, 8 ¼ inches).7 Two years later, Friend was a member of the American delegation to the 1906 Olympic Games in Athens, taking the bronze medal in the long jump while also competing in the 110-meter hurdles and discus.8

Following college graduation, Friend matriculated to the University of Chicago Law School and earned his degree in 1908. Admitted to the Illinois bar, he entered private practice handling mostly civil matters. Friend was also active in Jewish philanthropies and dabbled in local Republican Party politics.9 In 1916, he was appointed to the quasi-judicial post of master in chancery.10

Tabbed by Illinois Governor Frank O. Lowden to fill a temporary vacancy on the circuit court bench in September 1920, Friend was assigned to the criminal part that December. In May 1921, he was popularly elected to a full six-year term as a circuit court judge. All the while, Friend, like Judge McDonald, remained an avid Chicago White Sox fan.

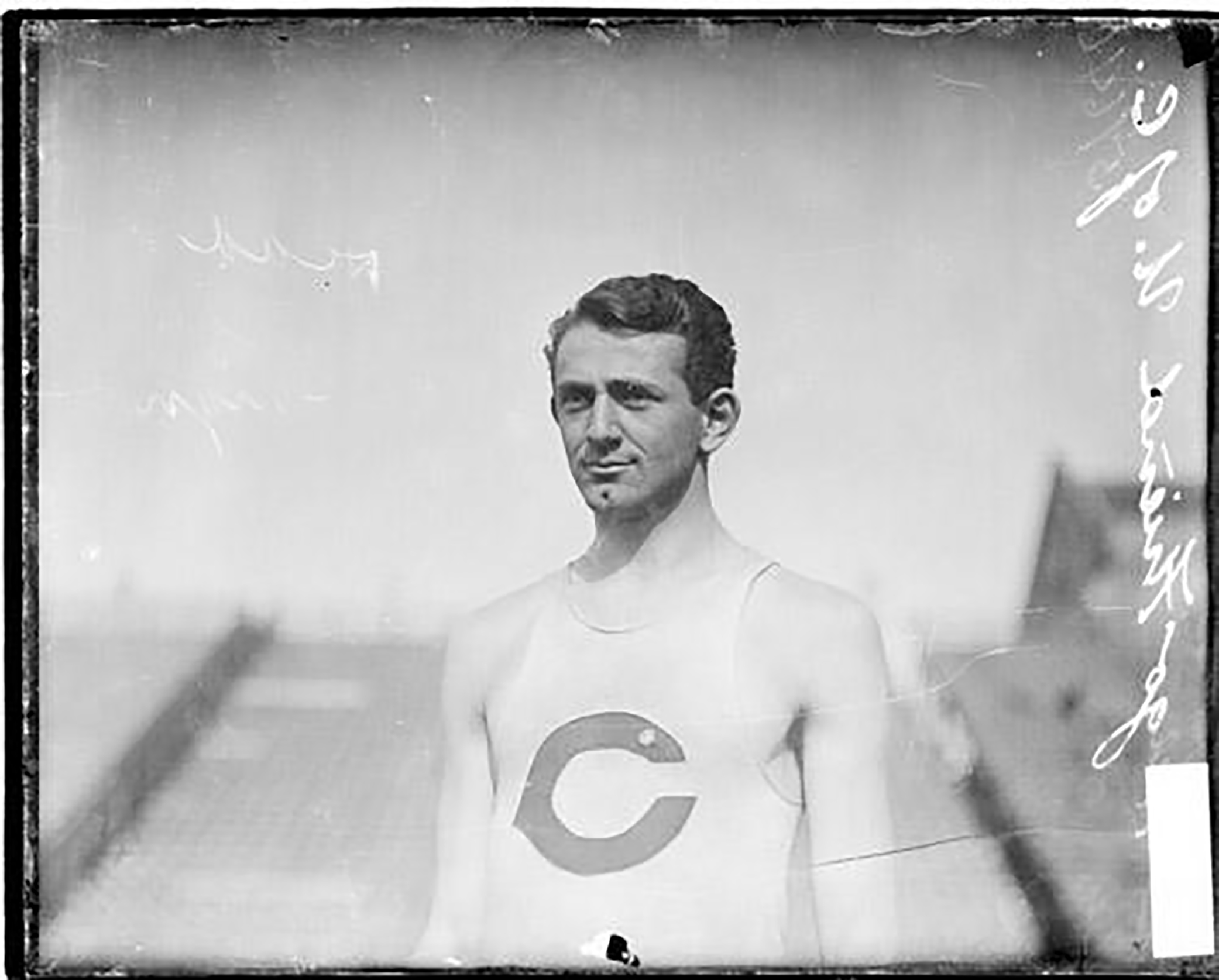

As a student at the University of Chicago, Hugo Friend was a track and field standout. In 1906, he was a member of the American delegation to the Olympic Games in Athens, Greece, taking the bronze medal in the long jump while also competing in the 110-meter hurdles and discus. (Photo: Chicago History Museum, Chicago Daily News Collection, SDN-051646)

Pretrial Motion to Dismiss Charges

In mid-June 1921, McDonald assigned the superseding indictments returned in the Black Sox case to Judge Friend.11 Among the laundry list of otherwise hopeless pretrial defense motions waiting for the court was a legitimate threat to the prosecution: a motion to dismiss the charges based on a ruling recently promulgated by a California court.

Analogous to the Black Sox situation, several minor league ballplayers and a gambler had been indicted for conspiring to rig the 1919 Pacific Coast League pennant race.12 But Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Frank R. Willis dismissed the charges, agreeing with the defense that the fixing of professional sporting contests was not prohibited by law. While game-fixing was reprehensible, “there is nothing in the penal code of California providing for the prosecution of the offenses named in the indictment,” the court declared. “The conspiracy if it existed, and if it was carried out, constituted a violation of contract. The remedy for that is in civil courts.”13

Willis’s ruling was at the forefront of arguments subsequently advanced by the Black Sox defense attorneys in pretrial motions to dismiss the indictments. If such arguments were embraced by Judge Friend, the Black Sox case would be over before it began. Modern-day analysis of the situation is hamstrung by the disappearance of the criminal trial transcript. To make matters worse, neither the courtroom arguments of defense counsel nor the prosecutors’ response is memorialized in newsprint. More important, no specifics of Judge Friend’s ruling are available. The press only blandly reported that the court “had denied a motion to quash the indictments.”14

Although the ruling’s underlying rationale is unknown, denial of the motion to dismiss seems the appropriate disposition. In reaching that conclusion, the author is mindful that considerations of fairness and due process demand notice that conduct is unlawful be published in advance of a criminal defendant taking the action for which he is to be prosecuted. And in 1919, neither Illinois nor any other jurisdiction had a statute that made the fixing of a professional sporting event illegal.15

But criminal laws proscribing various forms of fraud like theft by deception or obtaining the property of another by false pretenses or via a confidence game had long been on the books. Conspiracy to commit such offenses was plainly alleged in the Black Sox indictments, with the crime’s victims including duped White Sox bettors, as well as teammates of the accused and club principals, deprived of a legitimate chance at the winning share of Series proceeds.

It also cannot reasonably be asserted that the accused did not anticipate being criminally charged if their efforts to rig the World Series outcome were exposed. They well knew what they were up to was crooked — which is presumably why reputed fix mastermind Arnold Rothstein took measures to insulate himself from fix events. In sum, there was nothing unfair or unjust about holding the Black Sox defendants criminally accountable. The denial of their motion to dismiss the indictments was the right call.

Admission in Evidence of Grand Jury Testimony

When testifying before a Cook County grand jury in September 1920, White Sox stars Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and Lefty Williams each admitted that he had agreed to participate in the fixing of 1919 World Series games and that he had subsequently accepted a cash payment for that agreement.16 Their testimony also implicated Sox teammates in the fix scheme.

When it came time for trial, the Black Sox defense objected to the prosecution’s use of this highly incriminating evidence. According to the defense, the Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams grand jury testimony had been induced by broken off-the-record promises of leniency; thus, prosecutors’ use of that testimony at trial violated due process.

The credibility of this claim was assayed in a mid-trial hearing, conducted by Judge Friend outside the jury’s presence, that quickly devolved into a swearing contest. Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams testified that promises of non-prosecution were extended in exchange for their grand jury confessions. Testimony flatly denying that assertion was subsequently elicited from lead grand jury prosecutor Hartley Replogle and Charles McDonald, Cook County’s presiding criminal court judge.

At the conclusion of the proceeding, Judge Friend found the Replogle/McDonald testimony to be the believable account of events and denied the defense application to exclude the grand jury confessions. But prior to presentation of that evidence to the jury, the players’ testimony would have to be scrubbed of mention of their codefendants — Chick Gandil, Buck Weaver, Happy Felsch, Swede Risberg, and Fred McMullin. Wherever their names appeared in the grand jury transcript, the anonym Mr. Blank was to be substituted.17

Judgments on a witness’s credibility often turn on the ability to perceive or get a feel for that witness by means of the senses. Reading a transcript or newspaper account of a witness’s testimony does not equate to personal observation of the event. Because Judge Friend had the opportunity to see and evaluate the hearing witnesses firsthand that we, a century later, do not, criticism of his determination of who was telling the truth is of little moment. To that a cynic might add that Friend was not likely to hold that the testimony of his boss, Judge McDonald, had been false.

But Lefty Williams’ contradiction of various aspects of the Cicotte and Jackson testimony made the credibility call an easy one for the court. Once Judge Friend determined that the purported promises of leniency had not been made, the issue was settled. The sanction of prosecutors’ use of the grand jury testimony, with the names of codefendants camouflaged, cannot reasonably be faulted.

Exclusion of Expert Testimony Proffered by the Defense

Among the defenses offered on behalf of the accused ballplayers was total innocence — that they had not conspired to fix the World Series at all and had not deliberately tried to lose any games. The Series had been honestly contested. In support of this claim, Gandil’s attorney, James O’Brien, wanted to call as expert witnesses Clean Sox players Shano Collins and Nemo Leibold, as well as Reds pitcher Dutch Ruether. Presumably, the three were prepared to testify that they had detected nothing suspicious in the play of the accused.

Collins, Leibold, and Ruether all took the witness stand but Judge Friend sustained prosecutors’ objection to any testimony about the integrity of the defendants’ play. Nor were the three permitted to offer an opinion about whether the Black Sox had “played to the best of their ability” during the Series.18 As elsewhere, analysis of the court’s ruling is stymied by the loss of the criminal trial transcript. And no explanation of the court’s ruling appeared in newsprint. Analysis must, therefore, start from scratch.

Although every jurisdiction has its own unique rules of evidence, expert testimony is customarily admissible if three conditions are satisfied: (1) the proposed expert possesses sufficient expertise in his subject; (2) that subject is beyond the understanding of the typical juror; and (3) the expert testimony addresses an important issue in the case.

At the Black Sox trial, all of the above prerequisites to the admission of expert witness testimony were present. Collins, Leibold, and Ruether were accomplished professional baseball players whose expertise on the game was clear and indisputable. The art of throwing a baseball game was a subject beyond the understanding of the casual, at best, baseball fans seated on the jury.19 Four decades later, Happy Felsch memorably, if inelegantly, articulated how easy it was for a major leaguer to disguise his intentions from others: “Playing rotten, it ain’t that hard to do when you get the hang of it. It ain’t that hard to hit a pop-up while you take what looks like a good cut at the ball.”20 Whether or not the accused had thrown World Series games was central to the case.

The only explanation for the exclusion of expert testimony by Collins, Leibold, and Ruether that the author can conjure arises from the fact that the admission and extent of such testimony always falls within the sound discretion of the trial court. Perhaps Judge Friend was troubled that the defense experts were not neutral observers of World Series play but actual participants in game action. Three years later, when Joe Jackson’s back-pay civil suit against the White Sox was tried, the plaintiff’s expert player witness on the bona fides of Jackson’s performance, retired Phillies first baseman Fred Luderus, had not been a Series contestant. But on its face, Judge Friend’s expert testimony ruling is puzzling and almost certainly erroneous.

Exclusion of Rebuttal Evidence Proffered by the Prosecution

Because the legal mandate that grand jury proceedings remain secret was entirely ignored in the Black Sox case, the grand jury testimony of Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams hit newsstands literally within hours of its elicitation. Shortly thereafter, Felsch confessed his involvement in the World Series fix to Chicago Evening American reporter Harry Reutlinger. “I Got Mine, $5000 — Felsch” read a front-page headline in the newspaper’s September 30, 1920 edition.

During the criminal trial, prosecutors presented the jury with the grand jury confessions of defendants Cicotte, Jackson, and Williams. But in an inexplicable strategic blunder, the State’s Attorneys offered no evidence pertaining to the confession that defendant Felsch had made in his newspaper interview before the prosecution rested its case. Days later, prosecutors attempted to undo their oversight by offering Reutlinger as a rebuttal witness, claiming, implausibly, that the Felsch newspaper confession had only recently come to government attention. But Judge Friend was having none of it.

Because the Felsch defense had not put on a case, there was nothing to rebut. In barring Reutlinger’s testimony, Judge Friend lit into prosecutors, declaring that “negligence in the State’s Attorneys Office should not jeopardize a defendant’s liberty. You should have brought in this testimony during your case-in-chief. It is not rebuttal evidence.”21

The court’s ruling was inarguably correct. Generally speaking, rebuttal is restricted to evidence that tends to disprove or contradict proof presented by the opposing side. In a criminal case, the prosecution may offer rebuttal after all the defendants have rested. Rebuttal, however, does not afford the prosecution a second chance to present evidence that it should have offered during its direct case. In the Black Sox trial, the Felsch defense rested without presenting any witnesses or evidence. Given that, there was nothing to rebut.22

Final Instructions to the Jury

In a criminal case, the opposing sides may submit for the court’s consideration proposed instructions on the law for the jury. Such a submission is called a “request to charge.” A defense request sought to have the jury instructed that to convict, the prosecution proofs had to show not only that the accused had agreed to fix the 1919 World Series, but that in so doing, their conscious intent had been to defraud the public and/or the other victims specified in the indictment. Over prosecutors’ objection, Judge Friend accepted this charge request and so instructed the jury. The acquittal of all defendants on all charges followed.

Almost 70 years after the Black Sox were acquitted, a legal scholar attempted to explain this perplexing judgment (at least regarding some defendants) by positing the above instruction as the basis for the jury’s verdict.23 But this argument is a non-starter. A conscious intent to defraud was painfully self-evident. For the scheme of high stakes, in-the-know bettors like codefendants Sport Sullivan, Abe Attell, David Zelcer, et al., and fix financier Arnold Rothstein to succeed, others necessarily had to be defrauded. After all, who in their right mind would have wagered on Chicago if he knew that the World Series outcome was preordained? Or that star White Sox players had agreed to dump Series games? Nor could the fix plot proceed if White Sox owner Charles Comiskey or the Clean Sox got wind of it beforehand. If the defendants did, indeed, conspire to fix the World Series, their conscious intent to defraud was manifest.

Placing the onus for the jury’s verdict on the court’s instructions has another inescapable flaw. As the post-verdict disclosure of one anonymous juror made clear, the jury paid no mind to the law or the court’s instructions on it. The jury had resolved to acquit the defendants at the close of the State’s case — days before the court delivered its legal instructions to the jury. “We thought the State presented a weak case,” the juror said. “We felt from the time that the State finished that we could not return any verdict but not guilty.”24

This sentiment, of course, was expressed by a member of the same jury that joined a post-verdict celebration with the same players whom they had just exonerated. Those festivities concluded in the wee hours of the following morning with a chorus of “Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here.”25 Jurors who were so sympathetic to the defense did not need to parse a lengthy instruction on the law to find a reason to acquit them. Indeed, the notion that jurors seized upon an arcane aspect of fraud law to render its verdict borders on laughable. They intended to acquit the defendants long before the court even gave its final instructions.

The Effect of Court Rulings on the Jury’s Verdict

The proceedings in the Black Sox case were not flawless. No trial of a criminal case ever is. But the law does not require that defendants receive a perfect trial, only a fair one. And that is what Eddie Cicotte, Joe Jackson, and the others got.

Credit for this belongs largely to Judge Friend. He presided with a firm but occasionally tolerant hand. With the exception of the exclusion of defense expert testimony, his rulings on key issues were legally sound. And he treated the opposing sides equitably, his latent sympathy for the accused suppressed until after the jury had acquitted the defendants. At that point, Judge Friend let down his guard. He “congratulated the jury, saying he thought [their verdict] a just one.”26 The court then indulged with a smile the raucous courtroom celebration that followed.

In the author’s view, the only ruling from Judge Friend that had any real effect on the proceedings was his denial of the pretrial defense motion to dismiss the charges. Obviously, if the court had granted the application, there would have been no Black Sox trial at all. But otherwise, the court’s rulings and jury instructions did not matter. For at some indiscernible point in the proceedings, the 12 working-class men on the jury bonded with the blue-collar ballplayer defendants. Juror sympathy and affection for the accused was openly displayed during post-verdict restaurant festivities. There, a juror reportedly told Cicotte, “I know every man on this jury hopes that the next time he sees you it will be at the center of the diamond putting over strikes.”27 Another juror chimed in, “And we’ll be there in a box cheering for you and the rest of these boys, Eddie.”28

The jurors’ mindset abrogated any effect that court rulings and jury instructions might otherwise have had. The jurors liked the defendants and were not going to convict them. Period. This attitude embodies a mercifully rare courthouse phenomenon called “jury nullification.” And when it strikes, neither court rulings nor evidence nor anything else can deter a jury from returning Not Guilty verdicts. So in the end, Judge Friend’s evidentiary rulings and jury instructions had no effect on the outcome of the Black Sox case.

Postscript

Following the Black Sox proceedings, Judge Hugo M. Friend went on to a distinguished 46-year career serving on the trial and appellate courts of Illinois. He was still in judicial harness when he was felled by a fatal heart attack in his Chicago apartment on April 29, 1966. Judge Friend was 83 and had been listening to a White Sox game against the Cleveland Indians on the radio at the time of his passing.29

NOTES

1 “Lowden Puts Hugo Friend on Circuit Court Bench,” Chicago Tribune, September 17, 1920: 6. The vacancy was created by the death of another circuit court judge.

2 Although at times sympathetic to criminal defendants who came before him, Judge Friend was not soft on crime and displayed no qualms about sentencing convicted killer Harry Ward to death. See “Life Prisoner Is Ordered Hanged at Recent Trial,” Chicago Tribune, February 11, 1921: 17. Ward was executed on July 16, 1921.

3 During Black Sox-related civil proceedings conducted several years later, McDonald revealed that assignment of the criminal trial to Judge Friend was one of the few matters that opposing counsel agreed to in pretrial conference. See Jacob Pomrenke and David J. Fletcher, eds., Joe Jackson vs. Chicago American League Baseball Club: The Never-Before-Seen Trial Transcript (Chicago: Eckhartz Press, 2023), 219-220.

4 See e.g., William F. Lamb, “Jury Nullification and the Not Guilty Verdicts in the Black Sox Case,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Vol. 44, No. 2 (Fall 2015), 47-56.

5 Anglicized to Friend in America, Freund is the German and Ashkanazi Jewish word for friend. Several of Hugo’s siblings retained the Freund surname.

6 Although he never suited up for the varsity, Friend played football for his University of Chicago class teams as an undergraduate.

7 “Hugo Morris Friend,” Chicago Inter Ocean, June 19, 1904: 20.

8 A few years later, the competition was retroactively stripped of its Olympic Games status and retitled the 1906 Intercalated Games.

9 In the 1915 municipal election, Friend was an unsuccessful Republican Party candidate for alderman.

10 “Hugo M. Friend,” Prominent Alumni, University of Chicago, Vol. 13 (1921), 177. A master in chancery serves as an assistant to an equity court judge.

11 “Trial of Black Sox May Open Monday in Judge Friend’s Court,” Chicago Tribune, June 21, 1921: 19. The original Black Sox indictments had been administratively dismissed for strategic reasons by Cook County State’s Attorney Robert Crowe after a prosecution motion to indefinitely postpone its unready-for-trial case was denied by Circuit Court Judge William E. Dever.

12 A comprehensive account of the matter is provided by Larry R. Gerlach, “The Bad News Bees: Salt Lake City and the 1919 Pacific Coast League Scandal,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Vol. 6, No. 1 (Spring 2012), 35-74.

13 As quoted in “Crooked Baseball No Crime on Coast,” New York Herald, December 25, 1920: 8; “Borton-Maggert Indictments Quashed,” San Francisco Chronicle, December 25, 1920: 11; and other newspapers nationwide.

14 “The Baseball Trial Is On,” Kansas City Times, July 6, 1921: 8; “Ex-White Sox Lose Pleas and Trial Is to Begin,” New York Tribune, July 6, 1921: 5. Instead, newspapers devoted their coverage of the day’s proceedings to the jury selection process.

15 Specific sports corruption statutes were enacted nationwide in the aftermath of exposure of the 1919 World Series fix. But such statutes could not be applied retroactively to criminalize the conduct of the accused in the Black Sox case.

16 According to their testimony, Cicotte received $10,000 while Jackson got $5,000 of a promised $20,000. Williams also received $5,000.

17 Because it was not raised at trial, this essay will not address the issue of interlocking confessions. In brief, an interlocking confession is an admission of guilt by a criminal defendant that agrees in important detail with the confession of another defendant. Tricky, fact-sensitive constitutional issues must be resolved when confessing defendants are tried jointly. The core problem: If one confessing defendant exercises his Fifth Amendment right to remain silent at trial, the other defendant may be deprived of his Sixth Amendment right to confront and cross-examine an adverse witness if the first defendant’s confession is admitted in evidence.

18 As reported by the UPI in “‘Black Sox’ Mates Testimony Ruled Out by Court,” Pittston (Pennsylvania) Gazette, July 28, 1921: 1, and elsewhere. See also, “Refuses to Let Ex-Teammates Aid Sox Cause,” (Madison) Wisconsin State Journal, July 28, 1921: 1.

19 During jury selection, none of the 12 veniremen who were ultimately chosen for the panel professed to being much of a baseball fan.

20 Eliot Asinof, Bleeding Between the Lines, (New York: Holt, Rhinehart and Winston, 1979), 117.

21 As quoted in “State Loses More Ground,” Atlanta Constitution, July 30, 1921: 9; “Sox Win Again in Decision,” Des Moines Evening Tribune, July 29, 1921: 1; and elsewhere.

22 In contrast to Felsch, the defense of Chick Gandil as well as that of gamblers David Zelcer and Carl Zork presented testimony and other evidence. The court therefore permitted the prosecution to present rebuttal proofs against those accused.

23 James Kirby, “The Year They Fixed the World Series,” American Bar Association Journal, February 1, 1988.

24 “Jury’s Decision Fails to Make Black White,” Los Angeles Times, August 4, 1921: 11.

25 Dayton Daily News, Des Moines Evening Tribune, and Los Angeles Evening Examiner, August 3, 1921.

26 “Former White Sox Players Are Found Not Guilty of Conspiracy,” Los Angeles Times, August 3, 1921: 1; “Sox Are Acquitted of Throwing Games in ’19 Series,” New York Herald, August 3, 1921: 1.

27 “Jury Feasts White Sox in Night Café,” Los Angeles Evening Examiner, August 3, 1921: 1.

28 “Spectators Applaud When Jurors Free Former White Sox,” Austin Statesman, August 3, 1921: 8; “Jury and Exonerated White Sox Join in Party at Italian Restaurant; Stay Until Sunrise,” Des Moines Evening Tribune, August 3, 1921: 1.

29 “Hugo M. Friend, Judge 46 Yrs., Dies at Age 83,” Chicago Tribune, May 1, 1966: 50.