Macmillan: A researcher’s fond, tough look at The Baseball Encyclopedia

Editor’s note: This article first appeared in SABR’s “The National Pastime,” Vol. 6, No. 1, Winter 1987. To read more from the TNP archives, click here.

Conceived and nurtured by Information Concepts Incorporated (ICI), a systems company, and published by The Macmillan Company, The Baseball Encyclopedia: The Complete and Official Record of Major League Baseball (TBE), emerged publicly on August 28, 1969 during a press conference at Mama Leone’s Restaurant in New York City, where baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn hefted a copy of the six-and-a-half pound book for the photographers. The New York Times afforded the wondrous new reference work three reviews, a rare accolade for a sports publication. In one, Christopher Lehman-Haupt called it “… the book I’d take with me to prison, and I haven’t nearly the time to explain why.” Bill James recently called this first edition a major influence in· the sharp increase in big league attendance during the 1970s because it “… facilitated and thus encouraged baseball mania.”

In 1970, Macmillan issued a later version of the initial work differentiated by addition of an Appendix D containing a summary of 1969 statistics and not identified in the sequential numbering of editions. Macmillan subsequently published a second edition (1974), a third (1976), a fourth (1979), a fifth (1982), and a sixth (1985). The publisher has also brought out The 1986 Baseball Encyclopedia Update, and, to date, six statistical histories of major league teams, the title of each reading The Complete Record of (team name) Baseball. Together the six editions, the 1986 update, and the six team histories occupy two feet of shelf space, weigh forty-three pounds, include more than 16,000 pages and cost $231.50 at purchase

But the value of the series to baseball fans and researchers far exceeds cash or physical measurement. TBE editions have fascinated baseball followers from serious students of the game’s past to young fans whose baseball memories and interests span less than a generation. Sometimes called “the bible of baseball,” a characterization previously reserved for The Sporting News, TBE is so familiar to diamond buffs that mention of “the encyclopedia,” or “the Macmillan,” or just “Macmillan” leaves no doubt of identity.

BACK TO BEADLE

The statistical evaluation of individual performance in baseball is almost as old as the game itself. The Chicago Tribune’s claim on October 7, 1877 that its published batting averages were more accurate than the official figures of the National League illustrates how firmly the worship of totals and averages compiled from box scores had taken hold by the 1870s: “… some scorers have a habit of tampering with figures so as to raise up friends and put down enemies … not in newspaper scores but … in the private League official scores. To a certain extent, therefore, the newspaper scores are the most trustworthy.”

Since the time of the War Between the States guide serials like Beadle, DeWitt, Spalding, Reach, Sporting News, and others have carried official batting, fielding, and pitching totals and averages according to the scoring practices of their times, and with the addition of new statistical columns as scoring rules slowly expanded. Almost all of the early guides excluded men who played in fewer than a certain minimum of games per season—usually six, ten, or twelve. The practice of carrying full lines of statistics for all AL and NL players wasn’t established until the publication of the 1941 Sporting News Official Baseball Record Book. Full figures for play with two or more clubs during a season were not shown separately for each team until the 1943 guides appeared. League totals frequently failed to balance. For example, the 1946 AL batting and pitching averages fail to balance between offensive and defensive walks, hit batsmen, and sacrifice hits; and 1942 AL figures reconcile even less, with differing league batting and pitching totals for plate appearances, walks, strikeouts, hit batsmen, and sacrifice hits. There are more recent instances of imbalance, but over the last twenty years The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide has proven accurate and logical in its presentation of averages.

Baseball Magazine and railroad man John J. Lawres furnished the earliest collections of individual players’ career totals and personal facts in 1912. They followed up in 1916 with a new edition covering sixty-two contemporary pitchers and 145 other players in an expanded form, providing for each player: birth date and place; height; weight; side batted; side threw; either G, IP, W, L, PCT, SO, BB, H, ERA or POS, G, AB, R, H, SB, BA for every season in the minors and the majors, and notes stating dates and details of trades, sales, and releases. They did not, however, supply the statistics that were missing from official averages because of too few games played. In time, more columns were added. Commencing in 1939 The Sporting News put out a more elaborate rival of the same type, The Baseball Register, which, for many years included the playing records of contemporary players, managers, coaches, umpires, and some former star performers but now covers only players and managers. Both serials have continued through 1986, and in line with expansion, both have increased markedly the number of active players included.

Balldom: “The Britannica of Baseball” by George Moreland, 1914, provided year-by-year NL and AL team rosters, but Moreland didn’t include given names, nor did he furnish teams in the National Association, the American Association, the Union Association, the Players’ League, or the Federal League. Another great architect of baseball history and statistics, Ernest J. Lanigan, authored Baseball Cyclopedia in 1922. This work included an alphabetical register of the names, positions, clubs, and leagues of all AL, NL, and FL players from 1901 through 1921. Yearly supplements brought the register up through 1933.

The most important forerunner of TBE emerged in 1951: The Official Encyclopedia of Baseball by sportswriter Hy Turkin and S.C. Thompson, a baseball fan who had compiled a gigantic file of all-time player records. Sanctioned by commissioner “Happy” Chandler as “official,” and published by A.S. Barnes as “the jubilee edition,” its 620 pages included many well-researched features—like an all-time roster of umpires for six major leagues—but its essence was an 1871-1949 register of nearly 9,000 one-or-more game players or managers (NA, NL, AA, UA, PL, AL, FL), stating for each: date and place of birth; date of death if deceased; year; club; position(s); number of games, and either or both BA and W&L, for each season in the majors. Managers were noted as such. This initial volume was followed by a 1952 supplement and ten full revised editions, the last in 1979. A spin-off, All-Time Rosters of Major League Baseball Clubs, by Thompson, came out in 1967. It was revised in 1973 with 1965-1972 material added by Pete Palmer, who also edited the final editions of the encyclopedia, Turkin having died in 1957 and Thompson in 1967.

DEVELOPMENT

Gaps and obvious errors in official averages, the lack of many early records, difficulty in securing the records of players who appeared in only a few games, and frustrating discrepancies among existing gUides and registers had long since created a desire for an ultimate, complete, correct set ofmajor league records. But it wasn’t until the mid-1960s that the development of sophisticated computers which could absorb, retain, order, and output huge amounts of data finally made a project feasible. As the preface to the first and second editions of TBE noted, Information Concepts conceived the notion of building a data base from modern-style box score statistics for all major league games played from 1876 forward and an all-time player file of personal facts, team affiliations, and ultimately, from the data bases, individuals’ yearly and career batting, baserunning, fielding, pitching, and managing statistics. Successively, ICI:

- Enlisted the services of Lee Allen, historian at the Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum (and professor of the largest baseball demographic file extant) and John Tattersall (and his life-time accumulation of the game accounts and box scores, particularly critical to the nineteenth century portion of the project).

- Gained sanctions from Commissioner Kuhn, the AL, and the NL, for the published results to be the official records of the baseball establishments.

- Reached agreement for The Macmillan Company to be the publisher.

- Organized an outside research staff of baseball experts to find, analyze, organize, and record material from official game sheets, newspapers, and other available sources for input into the data bank (many of the volunteers became charter members of the Society for American Baseball Research in 1971 or later joined the society).

- Managed the research effort, the data input, the accuracy checks, and the ordering of the material for printing. As David Neft, ICI’s Research Director, summarized the final stage, “It took just seven hours to print … the book, but a year and a half to tell the computer what to do.”

Before the last stage was completed, a Special Baseball Records Committee (Allen; David Grote of the NL; Robert Holbrook of the AL; Jack Lang of the Baseball Writers Association of America; and Joseph L. Reichler of the Commissioner’s Staff) drew up a code of rules governing the record-keeping procedures needed because some past records are based on “definitions … either incomplete or inconsistent with the rest of baseball history”—like bases on balls being hits in 1887.

This code changed some old records, particularly nineteenth century ones. A questionable change was the disqualification of the National Association, 1871-1875, from major league status “due to its erratic schedule and procedures.” That may be a good reason to treat NA records separately, but it probably doesn’t justify denigrating the NA, which certainly was the major league of its day and was so regarded in the “official” encyclopedias of Turkin and Thompson. On the credit side, the committee affirmed that the majors should have one continuous set of records “without arbitrary division into nineteenth- and twentieth-century data.”

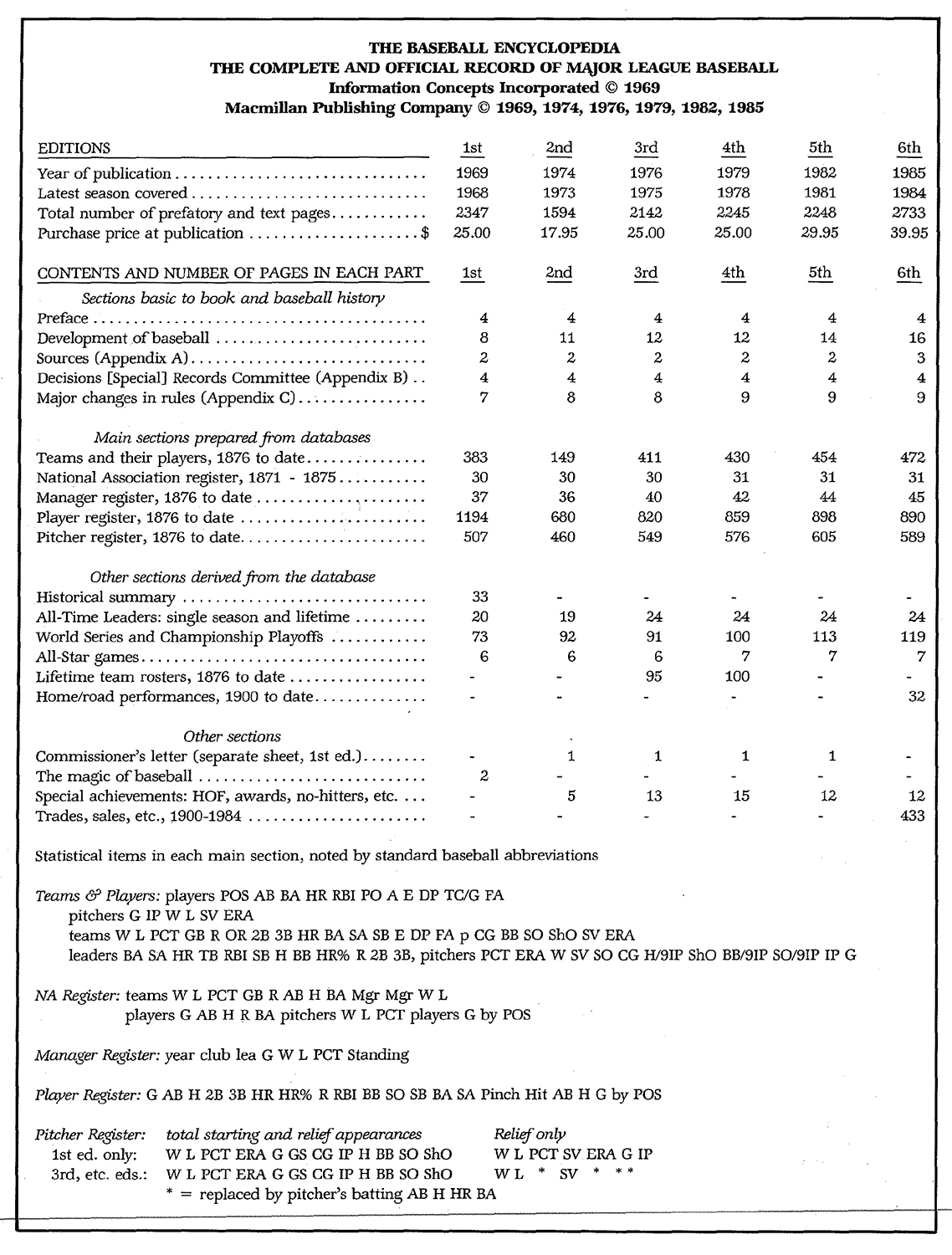

The player, pitcher, NA, and manager registers constructed from the ICI data bases dominated the first edition as they continued to dominate all subsequent editions. But other features merit attention also. The box on page 34 lists the subject divisions of each edition, the space allotted to each, and notice of the statistical column headings in the registers and “The Teams and Their Players.” The sections I’ve termed “basic to book and baseball history” shouldn’t be ignored:

- The original preface covered the development of the first edition. In later editions, the preface was updated, but the original text remained almost unchanged, with one exception: all mention of Information Concepts, the prime mover of the enterprise, was deleted from the third and all subsequent editions. (The partnership between ICI and Macmillan ceased before the second edition was prepared.)

- “Development of Baseball” is an historical account which belabors some events yet ignores others: the draft (as distinguished from the modern reentry draft), the rise of the farm system, the decline of the minors coincident with the growth of television audiences and other occurrences of mutual concern to the minors and the majors. Its length doubled by the sixth edition, with the new text devoted entirely to the years 1969-1985.

- “Sources,” Appendix A, lists the initial research materials: the official records (NL 1903 to date and AL 1905 to date); the collections of Allen and Tattersall and the files of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum; trade papers (Sporting Life 1883-1916, The Sporting News 1886 to date, The Sporting Times 1890; and 124 newspapers of thirty past and present major league cities).

- “Decisions of the Special Baseball Records Committee,” Appendix B, Rules 3 through 17 are logical and consistent with the principle of change only when necessary. Rule 15 errs in saying tie games of five or more innings were excluded from official player averages before 1885, inasmuch as the AA did include them before that year. Rule 17 lists all thirty-seven batters denied “sudden death” home runs before 1920, possibly because Babe Ruth was one of them.

- “Major Changes in Playing Rules and Scoring Rules,” Appendix C, is a useful adjunct to Appendix B and a helpful reference in itself. The rules affected by committee decisions are marked by asterisks. The latest TBE editions cover rule changes enacted through December 1978.

“Player Register” and “Pitcher Register” form the main substance of TBE. Besides the statistical items shown in the box, they furnish full names, nicknames, dates and places of birth and death, playing weights, heights, batting and throwing sides, close relatives who also made the majors, Hall of Fame membership, no-hitters pitched, and reasons for “career interruptions” exceeding thirty consecutive playing days (illnesses, injuries, suspensions, military service). This tremendous wealth of facts and playing statistics was a great achievement.

The forty-four person staff of the first edition obviously understood the essence of baseball records. It shows in their choice of which statistics to print from those available in the data bank and their rearrangements of batting and pitching columns from traditional sequences ofofficial averages into more logical groupings. The introductions they prepared for each ofthe ten parts concisely describe the content to follow, note all abbreviations and symbols employed, and illustrate every type ofsubsequent entry. Another mark of excellence was their creation of “The Teams and Their Players,” which set forth yearly league standings and certain key batting, baserunning, fielding, and pitching totals for each team and league, a rundown of teams’ personnel (regulars, prime substitutes, main pitchers, and managers) with some season totals, and lists of the top three, four, or five leaders in many offensive and defensive categories. This section nicely complements the player, pitcher, and manager registers.

The staff wasn’t perfect, though. Four practices adopted in the 1969 book and perpetuated in later editions seem less appropriate than the following recommended alternatives:

- For men who played on more than one team during a season, including full lines of statistics for performances with each club (as they were initially in the data bank) instead of lumping them together and breaking out only G and BA or G, W, and L per team. Such an arrangement would still occupy only two lines except in the few instances when a man played for three or more teams during the year.

- Alphabetize the registers by surnames and given names, instead of nicknames or familiar forms of given names. By using the standard method found in respected biographical compendiums the dilemma of what to call some early lesser-known athletes is avoided; the search to find a particular Smith, Jones, or Wilson is shortened, and the possibility of over-emphasizing a nickname known during only a part of a man’s life or baseball career is eliminated.

- Program sacrifice hits into the data bank and substitue SH for HR% in the batting records. The deterrent here may have been the in-and-out history of combining SH with other categories like SF and AB. Perhaps someday research will complete records of hit by pitcher so they too can be added.

- In “The Teams and Their Players,” add to batting totals team G, AB, H, and BB (all available in the data bank) by moving PCT and GB up and left under team names and eliminating duplication of the W and L columns.

One more criticism. A publisher’s note in the first edition reveals that “much of the source material that was used in the research of this book and the resulting compilations are being donated to the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, N.Y., for writers and researchers.” This material consists of thirty huge binders of computer printouts, one per league per season for each year of the four defunct majors and for the NL 1891-1902, and the AL 1901-1904 (ceasing just prior to the years for which official game sheets have been kept by those leagues). Each binder is arranged into team sections containing sheets for each player and the team, listing the date and statistics for each game played, with pitching records similarly entered on separate sheets. If printouts ever existed in the same form for NA 1871-1875, NL 1876-1890, 1903-, and AL 1905-, they have vanished from public notice. One source tells me they were destroyed in a fire. While the individual player files at the National Baseball Library in Cooperstown contain many obituary articles, death certificate copies, and completed questionnaires to back up the personal facts appearing in the registers, no collected evidence is available for the majority of former major leaguers. Discriminating consumers do not believe statements simply because they are in print, so if TBE is to be the ultimate authority it self-proclaims, it should try to collect and maintain proofs for every piece of personal information and every statistic printed and every change in subsequent issues. This source available to anyone on request.

The slip case supporting the first TBE omitted blurbs, but the dust jackets of succeeding editions all contain them. Naturally, they stress the updating process. They also call attention to revised and expanded text and advertise new features (but never the ones reduced or dropped). The encomiums call TBE “the bible of baseball” and say things like ” … never before has baseball been so thoroughly researched so carefully scrutinized … so painstakingly verified …” Taking these at face value you might expect that by now TBE had reached near perfection. It hasn’t.

FORMAT PROBLEMS

When Macmillan published the second edition in 1974, the only carryover from the initial group on the twelve-person editorial and research’ staff was John G. Hogrogian. The book listed the staff alphabetically without specifying their individual responsibilities but Red Smith in his May 26, 1974 New York Times column called Reichler the editor. Macmillan accomplished its stated objectives of updating records through 1973 and reducing bulk and price, eliminating 32 per cent of TBE’s length and 28 per cent of its retail cost. A jacket blurb said “Here, once again—fully updated—is the complete and official book of baseball records.” Neither the jacket nor the prefatory pages warned that a considerable amount of original material had been dropped:

- About 2,500 noncurrent players with less than 25 AB and pitchers with less than 25 IP and no won or lost decisions were cut to a single line: name, club(s), year(s), and BA or IP.

- Other pitchers who played little at other positions or did not pinch hit frequently were eliminated completely from “Player Register.”

- In “Pitcher Register,” relief pitching records were reduced to W, L, and SV, and the vacated space was used to insert pitchers’ brief batting records, G, H, HR, BA, “because a pitcher’s batting statistics are of relatively minor importance—and the Designated Hitter rule may eliminate pitchers’ batting entirely.” Why should a future possibility wipe out the past?

- The carefully researched “career interruptions” were dropped from the player and pitcher registers.

- “The Teams and Their Players,” renamed “The Teams Year-by-Year” omitted the lineup material entirely.

- Also dropped was the “Historical Summary” of charts and graphs showing yearly averages for many categories from 1876 through 1968, and the tables with yearly team totals and averages in fifteen categories for each NL, AA, and AL team covering the same seasons.

Reichler was credited with heading the editorial staffs of all later editions. In the third and following issues, Macmillan restored the 2,500 one-liners to equity with the others in the register and reestablished “The Teams and Their Players” by reinserting the lineups and their statistics, but the changes 2, 3, 4, and 6 above have not been reversed to date.

A new section, “Lifetime Team Rosters,” appeared in the third edition, was repeated in the fourth, then dropped. It contained all-time alphabetical listings of teams’ personnel from 1876 forward. Despite confusion between the St. Paul and St. Louis VA rosters and an occasional computer trick of forgetting the last season played for a club when the man had returned there following absence of a year or more, this was an appropriate and useful feature.

Several elements were added in the sixth edition. “Home/Road Performances” provided home and away records of won and lost and runs and homers made and allowed. It introduced factors designed to measure the influence of the home park on a team’s ability to score and prevent scores in home games and to compare a team’s performance in road games to league performance. Pete Palmer is credited for this feature. Also added were line scores for all League Championship, World Series, and All-Star games and statistics to the player and pitcher registers from the League Championships and World Series.

Another newcomer, “Trades,” lists every major league trade, sale, or free agent signing of 1900-84 by alphabetical order of the players involved. This material, differently arranged, had been published as The Baseball Trade Register by Reichler in 1984. A note promises that this record will be extended back to 1876. A good, solid piece, yes, but I don’t think it belongs in TBE. It uses 433 pages that I would rather see devoted to products of the central data base, such as pitchers’ batting statistics.

ACCURACY—GAINS AND LOSSES

With the voluminous content of the first edition in place, most of us expected that the inevitable errors would be corrected in subsequent editions. That this has not always happened is attested by a hot review of the fourth edition wherein the critic spent 800 words damning mistakes and misspellings concerning players of the 1970s, the omission of Dane Iorg, the failure to correct the listing that had Red Faber playing fifty-two games at first base in 1932, and sundry other failings. While that reviewer was so obsessed with the hole he overlooked the doughnut, he did make telling points about the need for careful editing and proofreading. My favorite goof is the record of Fred Clarke in 1899 as it appeared in the third edition:

| Edition | AB | H | BA | SA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 602 | 206 | .342 | .435 |

| 2nd | 602 | 209 | .347 | .440 |

| 3rd* | 209 | 206 | .986 | 1.254 |

| 4th | 601 | 209 | .348 | .444 |

*The .986 season pushed Fred’s career BA up fifteen points and carried over into “The Teams and Their Players” but he wasn’t credited with the 1899 BA title. Perhaps the computer balked.

Turning to purposeful changes and focusing first on their personal facts presented in the registers, obviously progress has been made in filling in the blanks observed in the first edition. To measure the progress I compared the first and sixth edition records of the 362 1904 major leaguers:

| No. of Facts Missing in 1969 | No. Added by 1985 | No. Still Missing | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Batting style | 64 | 1 | 63 |

| Throwing style | 32 | 13 | 19 |

| Height | 148 | 74 | 74 |

| Weight | 147 | 52 | 95 |

| Birth Date | 17 | 13 | 4 |

| Birth Place | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Death Date (of 362) | 16 | 14 | 1 |

| Death Place (of 362) | 31 | 30 | 1 |

| Full Names | — | — | — |

As far as I can tell, no new facts or figures have been added to the “National Association Register,” the orphan child of TBE. Either researchers have not produced anything of value or the publisher is disinclined to use whatever new material has been developed.

Acceptable accounting requires balanced figures, and so do baseball records if they are to be considered reliable and significant. Box scores must prove. Accumulated totals must balance between each team and its players, both per game and per season. Batters’ totals (H, R, HR, BB, HP) must reconcile with pitchers’ totals (H, R, HR, BB, HB). Putouts must equal Innings Pitched. The staff who planned and implemented the first edition understood this well, and their product shows it.

This statement from the first “Preface” was repeated in all later editions: “The last important step of the research phase began when the statistical information was fed into the computers…. If a team’s hits did not equal the hits of the individuals on the team, a message was printed along with the information and the item in question was further researched.” But this practice was certainly not followed by the staff of the second edition.

Players’ batting statistics were changed without compensating changes in the records of other players on the same teams or in the corresponding team and league totals. Later editions included even more unbalanced adjustments. The records of the 1890s, for example, were disarranged badly out of balance and have not been corrected to date. For the entire decade, only 15 percent of league figures (9 of 60) and 33 percent of individual team figures (37 of 112) reconcile completely for the categories G, AB, H, 2B, 3B, R, BA, and SA.

And there’s something interesting about many of the records that were changed. Taking 1897 as an example, it’s easy to see that there is a star quality to the twenty-three players whose 1897 statistics were modified. Besides Clarke and Wagner they were: BAL, Doyle, Keeler, Kelley; BOS, Duffy, Hamilton, Long, C. Stahl, Tenney; BRK, Griffin, F. Jones, Sheckard; CHI, Anson, Dahlen, Ryan; CLE, Burkett, Wallace; NY, G. Davis, Joyce, Parke Wilson; PHI, Lajoie; WAS, DeMontreville. All had long careers as regulars except Wilson, the Giants’ regular catcher in 1896 and the only one of these men who suffered negative adjustments. Only Wilson and Joyce and no AB or H adjustments for 1897 by the sixth edition. Excluding these two, the other twenty-one, including ten Hall-of-Famers, had career adjustments of +309 AB and +415 H among them by the sixth edition. I think it’s remarkable that of all the active players of 1897 twenty-one with long, outstanding careers should be the ones to gain more positive statistics both for 1897 and their careers? It’s enough to remind you of the Chicago Tribune’s 1877 diatribe over “…tampering with the figures so as to raise up friends… in … official scores.”

The comparisons of the six 1901-1904 seasons differ from those of the 1890s by being less radical: the “Player Register” changes were fewer and smaller, and the adjustments in team and league totals occurred more frequently and matched the sums of the register changes more closely. BA and SA percentages seemed to change properly—as consequences of changed AB, H, 2B, and HR totals in player records. The percentage of 1901-1904 team records in balance with their players’ records is about 69 percent, although league reconciliations are only about 42 percent (15 of 36).

Changes abound in the “Pitcher Register” of all revised editions, too, particularly in the second edition. Very few of those within the 1890-1904 span concern statistics other than won-lost totals, except in the cases of Cy Young and Kid Nichols. More than one hundred pitchers who labored between 1890 and 1904 had their won-lost totals adjusted for one or more of these seasons. By the sixth edition some of these adjustments accounted for seventy-three occurrences (of a possible 128) of team records not balancing with pitchers’ records. Fifty of the seventy-three imbalance instances of the 1890s and one of the four during 1901-1904 happened because the won-lost record of one pitcher on the team was changed. As Frank Williams detailed in his article “All the Record Books are Wrong” (TNP 1982) the assignment of wins and losses for the years before 1950 is not a simple matter. There is no doubt that many of the won-lost records of the first edition needed attention. But staff decision and team totals must still reconcile. You just cannot change one pitcher’s record without destroying the arithmetic balance. This elementary principle was clearly not followed by the staffs of all too many TBE revisions. The sixth edition extends a thank you to Frank Williams without stating for what, and I assume it was probably for his help in straightening out pitchers’ decisions.

Of all six editions, only the third and the sixth, with minor exceptions, include changes in league and team totals for the 1890-1904 period. Those in the third concern NL 1895-1897, 1899-1901, and AL 1901-1902. The sixth contains a noticeably larger number of such changes, all for the 1901-1904 years for both leagues. Every revision has included adjustments of player records, but the second has by far the greatest number, the most plus adjustments, and the most sweeping involvement of all-time stars. The staff of the sixth edition clearly tried to balance twentieth century records, but considering the massive deviations of the second edition, it seems too little, and in view of an eleven year interval since 1974—a bit late.

Quite apart from the problem of record-balancing, the numerous changes in players’ totals and averages has caused serious misapprehensions and confusions for fans, writers, and researchers. The records of Fred Clarke and Cy Young differ in all six editions even without counting Clarke’s astronomical 1899 BA. The figures for Burkett, Chesbro, Duffy, Hornsby, Walter Johnson, Radbourn, Speaker, and Waddell differ in five of the six books. The same is so in four of six for at least twenty-three other Hall-of-Famers, and many more less gifted players. The publisher could have helped by tipping off the reader and including in each revision a list of names of non-current players and pitchers whose records had been changed in the new edition, adding simple symbols denoting whether personal facts, statistical columns, or specific years were affected. Assuming close to a hundred entries per page, each list would have occupied only a few pages.

SUGGESTIONS

If the established pattern holds, a seventh edition of TBE should appear, in one volume again, about 1988 or 1989. If and when it does, as a fan and a researcher, unencumbered by the realities and responsibilities of marketing considerations, I hope the editors will take the following reformatory actions:

- Restore recognition of Information Concepts Incorporated in “Preface.”

- Drop “Development of Baseball” or have it rewritten by an historian.

- In “The Teams and Their Players,” add AB and H totals for each team each year.

- In all registers, restore pitchers’ full batting records, making room by eliminating “Trades.” Publish “Trades” separately.

- In all registers, when a player or pitcher performs with more than one club during a season, show his full statistics for each team.

- In all registers, rearrange the order of names according to proper given names instead of nicknames or familiar forms of given names.

- In the “Player Register” and the “Pitcher Register,” restore “career interruptions.”

- In registers, include lists of noncurrent players and pitchers whose personal fact information or statistical records have been changed from those of the sixth edition.

- In all records, observe strictly the arithmetic of baseball, even if it requires the same constructive steps as in the first edition to accomplish it.

Once it is published, I will grab a copy immediately, just as I have when each of its predecessors came forth, for truly it is “the bible of baseball”; I wouldn’t be without it.

FRANK PHELPS was the founding chairman of SABR’s Bibliography Committee.

(Click image to enlarge)