Twelve Men Out: The Middle-Class Chicagoans Who Made Up the Black Sox Trial Jury

Editor’s note: This article was originally published in the June 2018 edition of the SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter.

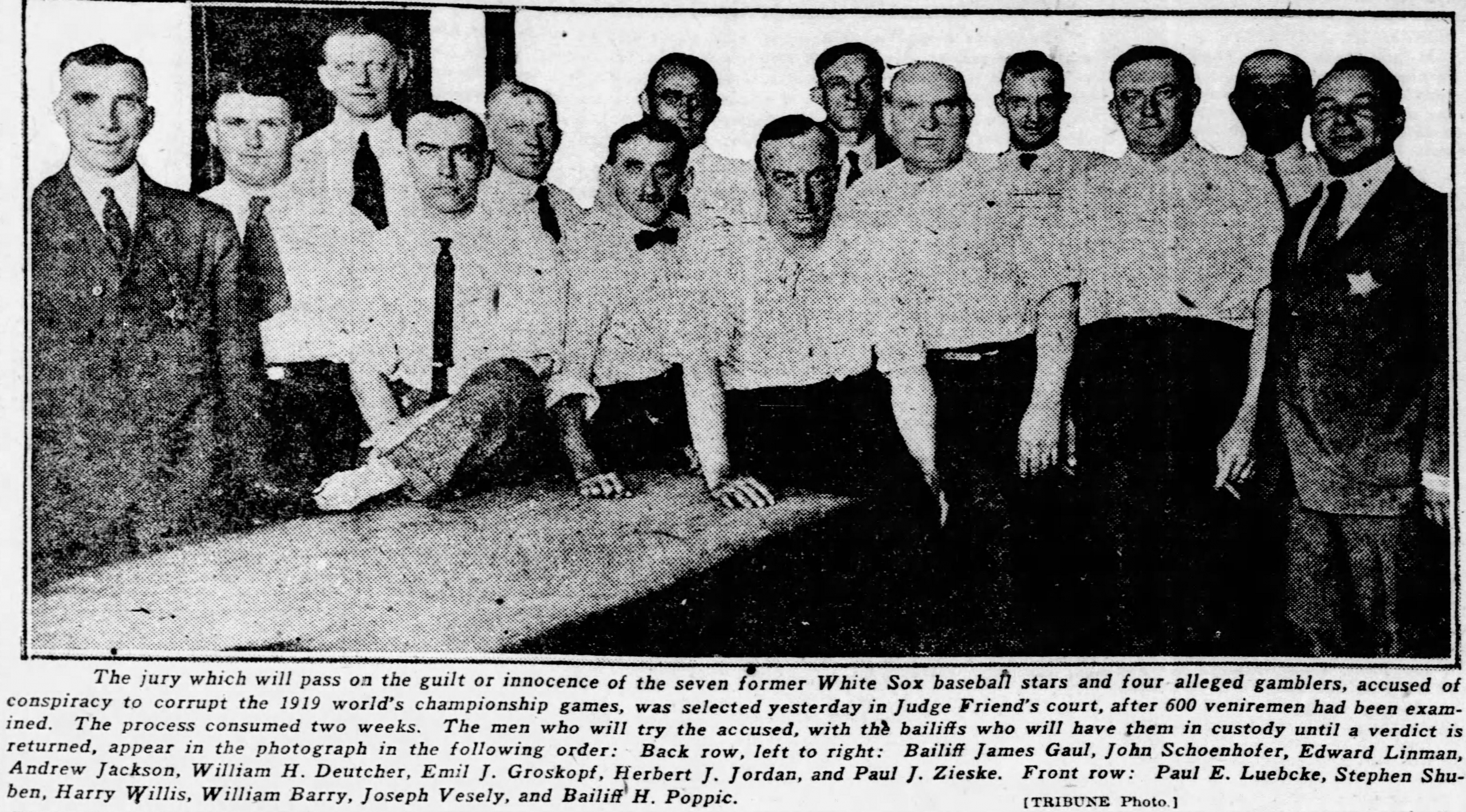

The Black Sox trial jury included, front row from left: Paul Luebke, Stephen Shuben, Harry Willis, William Barry (foreman), Joseph Vesely, bailiff H. Poppie; back row: bailiff James Gaul, John Schoenhofer, Edward Linman, Andrew Johnson, William Deutcher, Emil Groskopf, Herbert Jordan, and Paul Zieske. (Chicago Tribune, July 16, 1921)

Ultimately, the legal — as opposed to the moral — guilt of the accused Black Sox players during their criminal trial in 1921 rested on the judgment of the twelve jurors selected to determine their fate.

The jurors voted to take a vow of silence on why they reached their verdict1 and, so far as is known, the jurors kept that vow. The only indication of their thoughts came from an offhand remark by jury foreman William Barry to Judge Hugo Friend. As Friend recounted years later, Barry told him that the jury was particularly impressed by White Sox general manager Harry Grabiner’s testimony showing that the White Sox had earned large profits (i.e., not suffered any financial loss) in the years the Black Sox were throwing ballgames.2

Black Sox historian Bill Lamb, author of Black Sox in the Courtroom and the recognized expert on the trial, suggests that the effect of Grabiner’s testimony can be used to rationalize the jury’s verdict — i.e., acquit the players regardless of their legal guilt or innocence. He points to the fact that the jury took less than three hours to reach a series of verdicts on a complicated, multi-defendant case, suggesting the jurors took little time in evaluating the evidence presented.3

Given the nationwide interest in the case, and the multiplicity of defense attorneys, jury selection in the Black Sox trial took longer than anticipated. The prosecution and defense eventually went through the regular jury pool of 100 people, plus five more special venires of 100, for almost 600 prospective jurors in all, before settling on the final twelve.4

Most called “made every effort to dodge or otherwise avoid [jury] service,”5 perhaps fearing that the trial would be lengthy. One prospective juror claimed he was going out of state to be married. Another claimed a sudden onset of deafness. All the jurors were asked questions about their knowledge — or lack thereof — of baseball; whether they had ever played amateur or professional baseball; whether they had relatives who played professional baseball; whether they were baseball fans; whether they wagered on baseball games; and whether they attended the 1919 World Series.6

Chicago Cubs fans were barred as jurors, presumably because they would have a bias against the Sox players. One prospective juror was excused simply because he occasionally attended a Cubs game.7 In general, the prosecution wanted baseball fans on the jury, on the theory that baseball fans would be more outraged at game-fixing and thus more likely to vote to convict.

The prosecution quizzed jurors on whether they would accept accomplice testimony — foreshadowing the prosecution’s use of co-conspirator Sleepy Bill Burns as a star witness.8 As has often happened in practice, prosecutors feared that jurors would disregard the testimony of one “ratting out” his confederates.

In their questions to prospective jurors, lawyers for the defendants appealed to resentment that jurors might have toward wealthy team owners such as the Chicago White Sox’s Charles Comiskey. The Sporting News resented this attempt to “becloud the issue in question,” to excuse crookedness on the grounds that the players were poorly paid, that the players were (in the words of defense lawyers) little more than slaves, “bought and sold like negroes were before 1861.”

For The Sporting News, these lawyer tricks merely exposed how guilty the players were, tricks that “should get small consideration from any set of jurymen who know anything about the national game and who have any regard for justice.”9 Tricks or not, the defense meme seems to have influenced the jury.

After two weeks, only eight jurors had been selected. Impatient with the delays, Judge Hugo Friend threatened both sides with evening sessions to speed up the selection process. The judge also ended the practice of examining each prospective juror individually. He ordered all the candidates for the jury into the room as a group, and selected one lawyer from each side to deliver the competing theories of the case. This way prospective jurors could answer quickly whether their minds were open, avoiding the endless repetition of routine questions asked of each juror.10 The judge’s threats and orders worked — the next day, the final four jurors were selected.11

By all accounts, the twelve men selected were average, lower-middle-class Chicagoans, who ranged in age from 28 to 50. Ten lived in Chicago, their homes scattered throughout the city. The other two lived in the suburbs.

None of them professed any great interest in the game, although their post-trial behavior may suggest otherwise. After the not-guilty verdict was announced, “the courtroom was a love feast, as the jurors, the lawyers, and the defendants clapped each other on the back and exchanged congratulations. … Jurors then hoisted [Joe] Jackson, [Lefty] Williams, and several other defendants on their shoulders and paraded them around the courtroom before the celebrants finally gathered on the courthouse steps for a smiling group photo.”

Two jurors were quoted as wishing they would see Sox hurler Eddie Cicotte pitching for the Sox next year, and promising to cheer for him.12 Later that evening, jurors and defendants met at the Bella Napoli restaurant to celebrate together. The jurors and the ballplayers “left the restaurant together singing, ‘Hail, Hail, The Gang’s All Here.’ ” 13

The Black Sox appear to have received as fair a trial, before as fair a jury, as could be expected, given such a highly publicized, emotional, and polarizing case. But judging by this trial, the later Black Sox civil lawsuits in Milwaukee, and the 1919 Pacific Coast League game-fixing scandal14, the American justice system proved inadequate to police baseball.

Here are profile sketches of the twelve15 jurors:

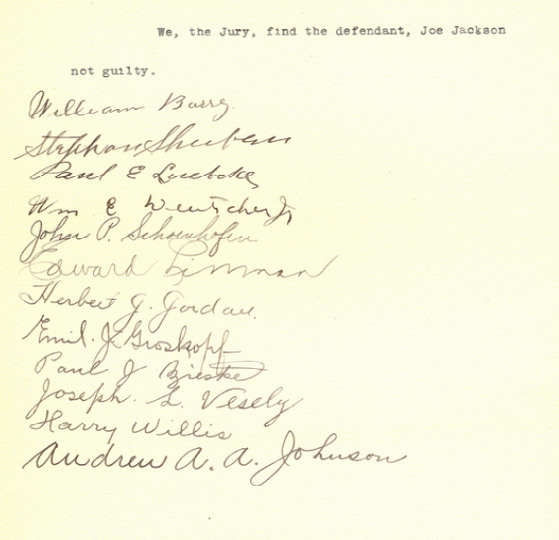

- William Barry, the eldest of the jurors, served as jury foreman. William Hamilton Barry was born June 15, 1871, in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, and died September 1, 1949 in River Forest, a Chicago suburb. In 1921 he was a hydraulic press operator, residing at 5949 West Lake Avenue.

- John Paul Schoenhofer, age 33, worked as a foreman for Darling & Co., packers, living at 5124 South Paulina. The son of German immigrants, Schoenhofer died on September 13, 1934, in Chicago.

- Edward Linman, age 36, was a clerk (timekeeper) for Illinois Steel Co., residing at 1366 East 61st Street. He died on February 12, 1934, in Chicago.

- Andrew Alfred Allen Johnson, often misnamed Jackson in trial coverage, age 32, was a store fixtures carpenter, residing at 2855 Union Avenue. By 1942 he owned a cabinet shop in Chicago. He died on October 12, 1975 in suburban Homewood.

- William E. Deutcher Jr., age 30, was an auto mechanic, living in the suburb of Forest Park. He died on December 25, 1965.

- Emil John Groskopf, age 32, was a clerk living in suburban Harvey, in charge of a store room for Whiting Company. The longest lived of the jurors, Groskopf died on March 16, 1989, in Bakersfield, California. His obituary was the only one of the jurors’ to mention his Black Sox trial service.

- Herbert J. Jordan, age 28, was a stationary engineer (janitor) at the Congress Hotel, living at 6121 Kenwood Avenue. The son of Irish immigrants, Jordan died on September 20, 1940, in a boiler explosion in Chicago.

- Paul Joseph Zieske, age 36, was a florist, residing at 1635 Olive Avenue. He had been a maintenance man prior to that, and by 1930 was a mechanic for a cemetery. The son of German immigrants, Zieske died on July 3, 1971, in Chicago.

- Paul Erdman Luebke, age 39, was an electrician for the telephone company, residing at 3926 North Hamilton. The son of German immigrants, Luebke died on June 14, 1940, in Chicago.

- Stephen Shuben (aka Stefan Shubenski), age 42, was a merchant, residing at 2524 North Springfield. The Polish-born Shuben had served in the US Army from 1901 to 1904, and worked as a machinist in 1918. He died on March 8, 1948, in Chicago.

- Harry Willis, age 34, was a “heater” for the Inland Steel Company, residing at 7933 Muskegon Avenue. Later employed there as a coke oven foreman, he died on October 11, 1947, in Chicago.

- Joseph Vesely, age 37, was a foreman for Air Motor Company, residing at 3155 North Ridgeway. The son of Bohemian immigrants, Vesely died on December 25, 1928, in Chicago.

The jurors’ signed not-guilty verdict for Joe Jackson on August 2, 1921. (Cook County Clerk of the Circuit Court Office)

Notes

1 Jacob Pomrenke, “Diamond Joe and the Black Sox jury celebration,” SABR Black Sox Scandal Research Committee Newsletter, December 2017.

2 William Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom: The Grand Jury, Criminal Trial, and Civil Litigation (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2013), 133, 136, citing the Eliot Asinof papers held by the Chicago History Museum. The substance of Harry Grabiner’s testimony can be found in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 29, 1921.

3 Lamb, 144. For a more detailed examination of jury nullification, see Lamb’s article “Jury Nullification and the Not Guilty Verdicts in the Black Sox Case,” SABR Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2015, accessed online at http://sabr.org/research/jury-nullification-and-not-guilty-verdicts-black-sox-case. Newspaper reports cited by Lamb indicate the jurors informally told reporters that the verdict would have been the same had the defense presented no witnesses, suggesting that the jury decided (legitimately or not) that the state had not proven its charges.

4 Chicago Tribune, July 15, 1921.

5 New York Herald, July 6, 1921.

6 Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1921. As an example, Special prosecutor Edward Prindiville asked jurors, “Do you believe baseball is an honest sport?” and “Do you believe in professional baseball?” See New York Herald, July 6, 1921.

7 Chicago Tribune, July 7, 1921.

8 Cf. Philadelphia Inquirer, July 6, 1921.

9 The Sporting News, July 14, 1921.

10 The Sporting News, July 21, 1921.

11 Lamb, 107.

12 Lamb, 142, 144.

13 Pomrenke, op cit.

14 For more on the Milwaukee lawsuits, see Lamb, Black Sox in the Courtroom, 189-193. For more the PCL scandal, see Larry Gerlach, “The Bad News Bees: Salt Lake City and the 1919 Pacific Coast League Scandal,” Base Ball: A Journal of the Early Game, Spring 2012, Volume 6, No. 1 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co.)

15 The lawyers tentatively accepted at least one other prospective juror, but that man (Michael F. Lidgen, a clerk for the city’s elevated railway) was later excused. See the Chicago Tribune, July 6, 1921.