Umpires in the Negro Leagues

This article was written by Leslie Heaphy

This article was published in The Negro Leagues Are Major Leagues (2022)

This article was originally published in “The SABR Book on Umpires and Umpiring” (SABR, 2017), edited by Larry R. Gerlach and Bill Nowlin.

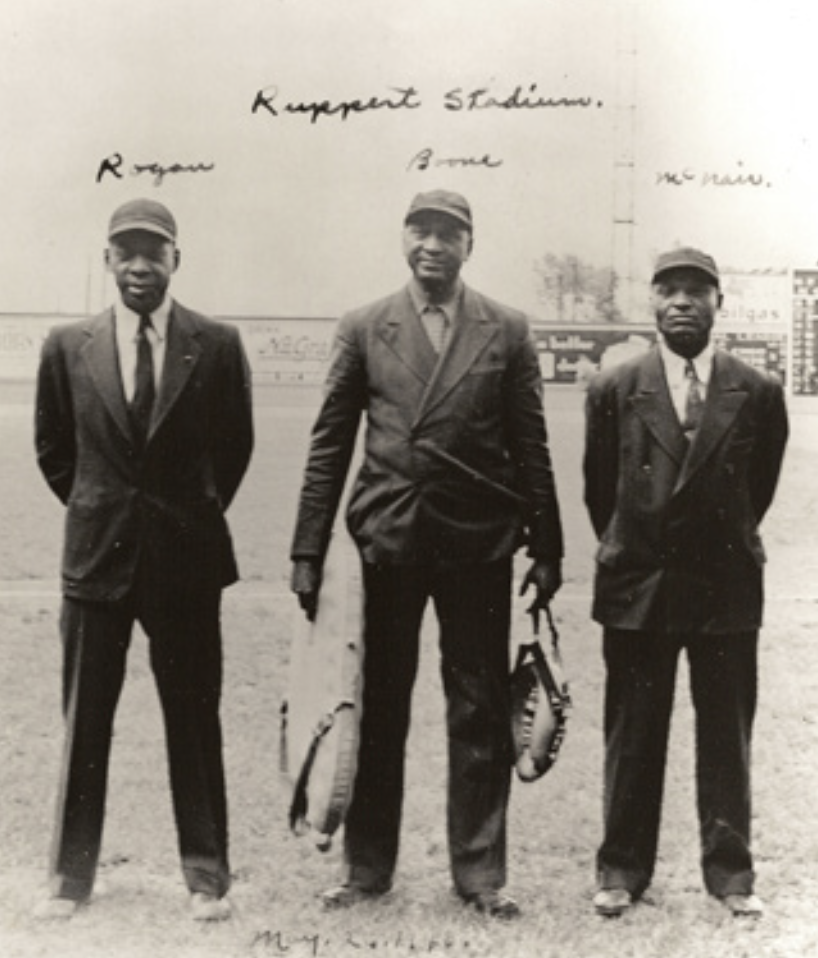

Umpires “Bullet” Rogan, Robert Boone, and Hurley McNair, Ruppert Stadium, May 2, 1940. (NOIR-TECH RESEARCH)

“What about our Negro baseball umpires? They are cussed, discussed, made the subject of all sorts of fuss. They are reviled and often as not, riled as they go about their highly-sensitive calling of calling ’em right, knowing that the fans in the stands are prejudicing them from the start, and that the players are the greatest umpire “riders” in the business. … All together, the life of the Negro umpire isn’t cheese and cherries by any means.” — Dan Burley1

Information about various aspects of black baseball can be difficult to find, and there are still lots of gaps in the story that need to be filled in — none more so than the role of umpires. Few stories in the newspapers ever said much about the umpires beyond their names unless something happened involving a bad call or a brawl. Some fans are familiar with the name Emmett Ashford as the first black umpire in the major leagues, but what about all the men who came before him? Who were these individuals who toiled in the shadows and never got any recognition for the difficult job they had on and off the field? Why did the leagues employ white and black umpires? How much of a difference did it make to have umpires who were white rather than black?

When the Negro National League (NNL) was created in 1920, one of the most important issues to be figured out was the way umpires would be chosen and paid. League President Rube Foster believed that the umpire needed to be in charge and provide order to every game. The umpire could maintain the legitimacy of the new league if he knew the rules and could command respect. There were mixed feelings among the owners about whether the umpires should be white or black. In 1920 most games had only two umpires rather than the four we see today. This made the role of the umpires even harder and more important. It was not until 1923 that the NNL owners voted to hire the first all-black crew for the league. Prior to that umpires were generally provided by the home team and were often white.

One of the earliest recorded stories of a black umpire involves Jacob Francis, who was chosen to represent Syracuse as one of the official umpires in the newly formed New York State League. In the census records of 1870 and 1880, Francis is listed as “mulatto.” He umpired at Stars Park throughout 1885 as one member of a three-man crew, becoming the first black umpire for an all-white league. In addition to umpiring, Francis managed the Syracuse Pastimes, a local black team. Francis first appeared in the 1870 census in Syracuse with his wife, Sarah, having come from Virginia. Fans generally supported Francis and even booed another umpire when he subbed for Francis. One news reporter said Francis “is one of the most popular men that ever officiated as an umpire before a Syracuse audience. An instance cannot be recalled where there was any trouble or delay in a game in which Mr. Francis officiated. He possesses an excellent judgment, is quick on his feet and gives his decisions promptly.”2

A 1909 Seattle article talked about Pete Johnson, a black umpire in the Jacksonville area during the late 19th century. Johnson appeared to be a fan favorite and well respected for his calls. Reporting on one game, a writer commented that “all the hotel guests were desirous of seeing Pete Johnson umpire as they were to witness the game itself.” He had a unique way of calling the game, deciding a runner who was out on the bases was “cancelled.” When a runner refused to leave the field after Johnson called him out Johnson simply said the player would be a “ghost runner.”3

Francis and Johnson were rarities: Most games involving black teams always had white umpires before 1923. That was partly due to the lack of trained black umpires, but more importantly most teams were owned by white men. They had control of the resources and therefore black men did not get the chance to umpire.4 Given the nature of race relations in the 1900s and 1910s, the idea that decisions by whites would be more accepted than those by blacks was not a stretch, and provided an additional rationale for the owners to justify using white umpires.

As early as 1910 the question of umpires for a proposed all-black league was being discussed. When Chicagoan Beauregard Moseley wrote about his proposed league, he noted many decisions that had to be made, but one he seemed to be adamant about was paid umpires. He said the umpires should receive $5 a game and be paid by the home team. Moseley did not comment on whether the umpires would be “race umps” or white arbiters but his proposal matched the pattern most often used by later leagues, with umpires provided by the home team. That added an extra burden to the men in black, who had to work harder to prove their impartiality.5

Foster did use black umpires for exhibition and benefit games. In 1910 he hired boxer Jack Johnson and vaudeville performer S.H. Dudley to work a benefit for Provident Hospital, a black-owned institution. The use of such stars gave the black community figures to look up to as role models. Foster himself umpired a benefit game in 1913, but for regular Chicago American Giants contests he used white umpires like Goeckel.6 With the creation of the NNL in 1920, Foster recognized the importance of umpires, writing in a 1921 column, “Future of Race Umps Depends on Men of Today.” He used this column to explain why the new league would be using white umpires rather than black. Foster’s basic explanation was simply that black men lacked knowledge of the rules. Opportunities were just not present, but the NNL was not a charity; it was business.7

Since there were no professional schools for black umpires, many of the best African American umps were former players who relied on their knowledge of the game from personal experience. For example, Newark Eagles first baseman-outfielder Mule Suttles umpired after he retired in the late 1940s. Pitcher Billy Donaldson turned to umpiring in the 1920s and 1930s, while second baseman Mo Harris umpired from the 1930s through the 1940s after his career with the Homestead Grays ended. Local Cleveland sports star Harry Walker umpired for the Cleveland Bears in 1939 to try to help support black baseball in his community. Cincinnati native Percy Reed played second base for a local athletic club and the Lincoln Giants. He started umpiring in 1929 and from 1935 to 1947 he called every Sunday game played by black teams in Cincinnati. Reed worked as part of a local two-umpire team with Harry Ward, known locally and in the papers as Wu-fang. Reed learned his trade from Bill Carpenter, who was an umpire in the International League.8 Hurley McNair, a pitcher and outfielder for a number of Negro League clubs, umpired after he retired as a player in 1937. He traveled for league games until his death in December 1948.9

The Baltimore Black Sox employed black umpires as early as 1917 when Charles Cromwell was hired by owner Charles Spedden. Cromwell umpired in the Negro Leagues through the 1947 season. In 1923 Rube Foster tried to hire Cromwell as part of a new team of African American umpires for the NNL. Foster wanted the best umpires and felt that white umpires had provided that in the first years of the league. With the creation of the Eastern Colored League (ECL) in 1923, Foster felt the time was right to find the best black umpires he could. His first hire was Billy Donaldson from the Pacific Coast League, and then he went after Cromwell. Cromwell turned Foster down to stay with the Black Sox after Spedden hired Henry “Spike” Spencer from Washington, D.C., to join him as the team’s umpires.

Spedden proved he wanted the Black Sox to succeed by spending money on the team, and so Cromwell opted to stay and umpire at the Maryland Baseball Park. By 1924 Spedden vowed to use all black umpires for Black Sox games, a move some said “is bound to meet with favor.”10 Cromwell’s choice did not turn out to be the best when the ECL decided in 1925 that teams should not hire their own umpires as had been the practice. This put Cromwell and Spencer out of work. Cromwell came back in 1926 when the ECL gave back the hiring of umpires to the teams. In 1927, when George Rossiter took over operations for the Black Sox, he fired Cromwell and Spencer. Rossiter felt that black umpires were not yet competent and that he would use white umpires until they were. Cromwell found work in a minor black league in the South before returning to umpire for the Baltimore Elite Giants through 1947. Cromwell’s career was like that of so many of the other black umpires, who always had to fight to prove they were as worthy as white umpires.11

Bob Motley umpired in the Negro American League from 1947 through 1958. (COURTESY OF BYRON MOTLEY)

When the Negro National League was being formed, Rube Foster talked with the press about a variety of subjects vital to the league’s success. One of those topics was umpires, who Foster stated needed to be totally in charge. Their decisions would be final and then needed to be supported by the league. Foster wanted “utmost good order on the ball field.” He saw the league as an investment, a business venture, and so the right arbiters would be essential to the success of the league. Foster commented, “I think an ump should be pacific but firm, positive but polite, quick but unshoddy, strict but reasonable.”12 On the question of the use of white versus black umpires, Foster wanted to use African American men but believed that there were not enough available and that anyway many people would accept the decisions of white umpires more readily. Reporter Charles Marshall thought colored umpires should be given a chance but agreed with Foster about white umpires. He wrote, “Of course we know that some players as well as some managers and fans alike feel that the white umpire’s decision carries more weight and generally comes closer to the right decision than the colored official. In most cases just because he is white.”13

With the creation of the Eastern Colored League (ECL) in 1923, the leagues continued serious discussions, deciding to hire all black umpires for the NNL. Reporter Frank Young began a campaign to hire black umpires in 1922. He called for training of black men and at the same time criticized the mistakes of white umpires. He tried to counter Foster’s concern that black umpires would be swayed by the cheering of black fans rather than engage in good decision-making. Young used his column to highlight the work of men like Jamison in Baltimore and Donaldson in California to show that there were African American men capable of umpiring for the league.14 Kansas City was the first of the cities to use two black umpires, Billy Donaldson and Bert Gholston.

Foster hired six black umpires for the league, with two-man crews responsible for different cities. Leon Augustine and Lucian Snaer worked around the Milwaukee area while Caesar Jamison and William Embry worked the Indianapolis region. When Foster failed to hire Charley Cromwell, he had to look harder for qualified men. Tom Johnson was the last of the original hires, being used as a rotating umpire.15

Finding arbiters with the necessary qualifications and abilities to control the game and the situations that could arise proved difficult from the beginning to the demise of the Negro Leagues. While owners like Foster and Kansas City’s J.L. Wilkinson favored all-race crews, they also knew having qualified umpires was even more important. Foster would not even use black umpires for Chicago American Giants games, preferring to pay white umpires while black umpires sat idle.16 By the end of the 1925 season, Foster released the black umpires who had been hired by the league and went back to the practice of the home team providing the umpires.17 At the end of the season the other owners hired back four of the six men who had been let go. These men continued to work for the league through the 1927 season without significant incident.

After Foster left the NNL in 1926, black umpires still had a difficult time being hired. However, when the short-lived American Negro League was created in 1929, it hired black umpires led by former players Bill Gatewood, Judy Gans, and former umpire Frank Forbes. Because of the Great Depression, pressure on the owners increased to give black men a chance. Unfortunately, the ANL collapsed after the 1929 season, ending one of the best opportunities for black umpires to be hired. Chicago Defender reporter Al Monroe stated in more than one column that black umpires needed to take better control of the game, they need to be less tentative and show control if they wanted respect. Without control they would never find regular employment.18

Umpires always had a tough time with players and fans who did not want to listen, but Negro League umpires often had a tougher time without much league support. Bert Gholston believed that the umpires always worked with the fear that they would be attacked and the league would not support them. He stated, “Several of the teams of the Negro National League are still under the impression that they shouldn’t take orders from the colored umpires. Several of them were threatening to jump on the umpires.”19

In 1934 NNL Commissioner Rollo Wilson tried to improve the situation by imposing fines and suspensions. One particular target was Jud Wilson, who had a temper and a reputation for attacking umpires. Wilson’s $10 fine was not much of a deterrent. By 1936 things had gotten so bad that $25 became the fine with a 10-day suspension for assaulting an umpire. New league secretary John L. Clark created a schedule for the three league umpires, Ray “Mo” Harris, John Craig, and Pete Cleague. The other umpires would still be chosen by the home team, which encouraged charges of favoritism. Unfortunately for the umpires, without strong support from league officials, they were pretty much on their own. Longtime umpire Virgil Blueitt stated, “If the club owners would order their managers and players to abide by the umpires’ rulings, much of this trouble could be avoided.”20

Another veteran umpire, Frank Forbes, was attacked on June 5, 1937, by New York Black Yankees players, and just a few games later he got into an altercation with Newark manager Tex Burnett. A month later Forbes and fellow umpire Jasper “Jap” Washington were attacked in their dressing room by Baltimore Elite Giants players. Washington resigned when nothing happened to the players involved. League honchos Gus Greenlee and Cum Posey finally responded with tougher policies, but the enforcement was lax depending on how a team’s players were affected. For example, when umpire James Crump forfeited a game, manager George Scales attacked him and the league let Crump go without any hearing at all. The lack of official support made an already hard job even more difficult for umpires, who earned no real respect for just doing their job.21

A reporter for the Kansas Whip stated that the “weakest link in a game is found in the set-up of umpires, which is limited to three.” He included a variety of criticism from around the league about the umpires not being harsh enough in their actions towards players who broke the rules.22

In 1944 Dan Burley wrote about the abuse umpires took for little pay. He reprinted a letter he received from Fred McCrary, a longtime umpire in the NNL. McCrary was upset at the lack of attention paid to umpires. For example, he worked in every East-West game from 1938 through 1944 and all the umpires got for each game was $10 and expenses. When McCrary asked for more money, the owners told him the umpire was not important for the game.23 Not all agreed with that assessment, as there were owners and players who treated umpires respectfully. By the 1940s some were also concerned about improving the respect because they feared the violence on and off the field might hurt the increasing push for integration.

In 1945 umpire Jimmy Thompson had his nose broken by player Piper Davis and pursued legal action against him since the league did little. Thompson won his case, though Davis only paid $230 in court costs. Later, President J.B. Martin added a league fine of $250 and indefinite suspension when the true story of the fight came out. Sometimes things got so bad that the police had to be called in to restore order. While police help was necessary it did not help the umpires exercise true authority. Sadly, it happened with both white and black umpires, as evidenced by Goose Curry harassing white umpire Pete Strauch until the police escorted Curry off the field. The Chicago Cubs finally raised the rent on Wrigley Field to keep black teams from using it if they could not control their players.24

Even the minor Negro Leagues had regular discussions about umpires and their roles. The Texas-Oklahoma-Louisiana League (TOL) decided in 1929 to hire four umpires who would be paid by the league. The league officials hoped this would give the umpires more authority and lessen incidents on the field. The Florida State Negro League in 1949 followed the pattern of having the home teams provide the umpires. But at the winter meetings before the 1950 season, discussion about the umpires’ situation dominated the talks. The league decided to hire two umpires, Williams Washington and Archie Colbert, and have the “balls and strikes” umpires travel around the league. At the same time, league President Skipper Holbert let two other umpires, Gus Daniels and Charles Merrit, go for inefficiency and misconduct.25

At the annual East-West Classic the leagues often used both Negro League and white minor-league umpires for the contest. Having a bigger pool to draw from allowed the Classic to have four umpires which often meant better control and legitimacy for the game. The only real difference in rules for the minor-league umpires was the fact that the spitball was legal in the Negro Leagues.26

The best-known black umpire from the Negro Leagues was Bob Motley, who in 2016 was the last living umpire from the leagues. Motley was born in Autaugaville, Alabama, in 1923, the sixth of eight children born to parents who were sharecroppers. Motley’s father died when he was 4, making it even tougher on the family to survive. Motley served in the US Marine Corps during World War II, earning a Purple Heart for a wound. While serving in the Marines, Motley umpired a few pickup games and discovered a career that would take off after the war. He umpired for over 25 years in the Negro Leagues and white minors. Umpiring from 1949 to 1956 in the Negro Leagues, Motley got to see some of the best players of the day and even umpired the 1953 and 1954 East-West Classics. Motley commented on umpiring, “An umpire has got to have guts. And force right; an ump can count on being no one’s friend — at least while on the diamond.”27

Motley attended the Al Somers Umpire School twice and graduated at the top of the class each time. His high scores did not help in the face of segregation; he never umpired above the Pacific Coast League.28 Motley recognized that umpires were not treated well by anyone. For example, he commented, “It was pretty common in the Negro Leagues, that if the catcher didn’t like the way an umpire was calling balls and strikes, he would purposely let a pitch go by and let it smack the umpire right in the facemask. That happened to me at least a half a dozen times.”29 After he called Hank Bayliss out on strikes and threw him out of the game, Bayliss came after Motley with a butcher knife on the bus home. The fans were even worse than the players in their continual comments. Motley said most fans had a favorite chant, “Kill the umpire, Kill the umpire!” You heard the chant so often you just expected it. Fans loved to blame the umpire when their team lost.30

While Motley has received some attention in his later years and Emmett Ashford is known because he was the first African American umpire in the majors, Julian Osibee Jelks never really got a shot. Jelks umpired for four years in the Pacific Coast League but never got a call to the majors. Before umpiring in the minors, Jelks was discovered by Alex Pompez when he came to New Orleans with his barnstorming Negro League teams. Pompez was so impressed with Jelks that he hired him to travel with his clubs in the mid-1950s. By 1956 Jelks got his first chance in the white professional leagues and began his climb to Triple A. Jelks umpired until the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and then he stopped, fearing he or his family might become targets. In 2008 Jelks was invited as a guest to the major-league draft where teams symbolically selected a former player from the Negro Leagues.31

Throughout the history of black baseball and the Negro Leagues, the issue of who would act as arbiters for their games was always a concern. While Rube Foster and other owners might have favored in principle hiring black men as umpires, they were businessmen first and needed to put the best product on the field. This led to decisions to hire white umpires most of the time based on the beliefs that they knew the rules better and could control the behavior of players and fans. With that said there were still many fine black umpires, from Jacob Francis to Julian Jelks. Sadly, good umpires rarely get noticed and their stories are not told, making it hard to track them down and give them credit for their contributions.

LESLIE HEAPHY is an associate professor of history at Kent State University and has been a SABR member since 1988. She is the chair of the Women in Baseball Committee and serves on the committee for SABR’s annual Jerry Malloy Negro League Conference. She is the author/editor of six books on baseball history and editor of “Blackball,” a national peer-reviewed journal on black baseball.

Notes

1 Dan Burley, “Chicken-feed for Negro Umpires,” in James Reisler, Black Writers/Black Baseball: An Anthology of Articles From Black Sportswriters Who Covered the Negro Leagues (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2007), 136.

2 Sean Kirst, “In Syracuse, A Groundbreaking Umpire Finds Himself Called Out,” syracuse.com, February 17, 2011.

3 “Black Umpire Springs New One in Ball Game,” Seattle Times, January 31, 1909: 14.

4 Scott C. Hindman, “Blacks in Blue: The Saga of Black Baseball’s Umpires, 1885-1951,” Bachelor’s Thesis, Princeton University, 2003, 18-19.

5 “Tentative Plan National Negro Baseball League of America,” Chicago Broad Ax, November 26, 1910.

6 “Diamond Dashes,” Indianapolis Freemen, August 6, 1910; “Benefit for the Old Folks Home,” Chicago Defender, August 20, 1913.

7 Rube Foster, “Future of Race Umps Depends on Men of Today,” Chicago Defender, December 31, 1921.

8 Brent Kelley, The Negro Leagues Revisited (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2000), 32-35.

9 “Hurley McNair,” pitchblackbaseball.com.

10 Baltimore Afro-American, January 1924; “Best in League,” Baltimore Afro-American, September 11, 1926: 9.

11 Gary Cieradkowski, “Charles Cromwell,” Infinitecardset.blogspot.com; “Black Sox Want Cromwell Here,” Baltimore Afro-American, March 30, 1923: 14.

12 Dave Wyatt, “Chairman Foster’s View on Grave Subjects,” March 27, 1920, paper found on negroleagues.bravehost.com.

13 Charles D. Marshall, “Will Colored Umps Be Given a Tryout?” March 27, 1920 paper found on negroleagues.bravehost.com.

14 “Demand for Umpires of Color is Growing Among the Fans,” Chicago Defender, October 9, 1920.

15 “Seven Colored Umps Signed for League,” Kansas City Call, April 27, 1923.

16 “Rube Foster’s Sportsmanship,” Chicago Defender, July 11, 1924.

17 “Kansas City the First City to Use Negro Umpires,” Kansas Advocate, April 27, 1923; “Change the Umpires.” Chicago Defender, August 19, 1922; “Foster Explains Action in Releasing Umpires,” Pittsburgh Courier, August 22, 1925.

18 Al Monroe, “Speaking of Sports,” Chicago Defender, July 21, 1934.

19 “Gholston Says It’s Hard to Umpire in This League,” Chicago Defender, August 28, 1925.

20 Neil Lanctot, Fair Dealing and Clean Playing: The Hilldale Club and the Development of Black Professional Baseball, 1910-32 (Syracuse: Syracuse University Press, 2007), 176; Leslie Heaphy, The Negro Leagues, 1869-1960 (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland and Company, 2003), 110.

21 Lanctot, 176-77.

22 “National Association of Negro Baseball Clubs,” Kansas Whip, July 17, 1936.

23 Dan Burley, “Chicken Feed Pay for Negro Umpires,” September 9, 1944, in Jim Reisler.

24 Lanctot, 180, 181.

25 E.H. McLin, “Official of Negro League Swinging Ax on Umps,” St. Petersburg Times, May 30, 1950.

26 Dave Barr, “Monarchs to Grays to Crawfords,” MLB.com/blogs; Kansas Plain Dealer, August 20, 1948.

27 Byron Motley, Ruling Over Monarchs (Champaign, Illinois: Sports Publishing, LLC, 2007), Introduction.

29 Bob Motley as told to Byron Motley, “ ‘No, I’m a Spectator Just Like You’: Umpire in the Negro American League,” Baseball Research Journal, Fall 2010.

30 Bob Motley.

31 Bill Madden, “Black Umpire Missed his Calling in the 1960s,” New York Daily News, February 10, 2007; Jay Levin, “Julian Osibee Jelks, 1930-2013: Pioneering Umpire Built a New Life Outside Baseball,” NorthJersey.com, July 4, 2013.