Columbia Park II: Philadelphia American League, 1901–08

This article was written by Ron Selter

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

Columbia Park was the second ballpark in Philadelphia to carry the name. The first Columbia Park had been used by the National Association Philadelphia Centennials for all of two months in 1875. Columbia Park II opened for baseball on April 26, 1901, as the first home park of the American League Philadelphia Athletics. The wooden ballpark had been quickly built before the start of the season on a vacant lot that had been leased for 10 years by the A’s manager and part-owner Connie Mack. Columbia Park was built almost entirely of wood–only the front or street side of the main entrance was brick. Unlike many of the other Deadball Era wooden ballparks, this one never burned.

The park site consisted of an entire rectangular-shaped city block located in North Philadelphia. The ballpark site was bounded on the north by Columbia Avenue, on the south by Oxford Street, on the west by 30th Street, and on the east by 29th Street. The location of the ballpark was not far from downtown Philadelphia. The grandstand and home plate were located in the southwest corner of the park site. This park site, although consisting of the entirety of one city block, was not large: 400 (east-west) by 455 feet (north-south) and amounted to 4.2 acres. By comparison, other wooden Deadball Era major league ballparks occupied sites ranging from 3.9 acres (League Park III in Cleveland) to 9.6 acres (American League Park in New York). The 400 foot (east-west) dimension, along Oxford Street on the south and Columbia Avenue on the north, limited the extent of the ballpark’s right field dimension.

The park site consisted of an entire rectangular-shaped city block located in North Philadelphia. The ballpark site was bounded on the north by Columbia Avenue, on the south by Oxford Street, on the west by 30th Street, and on the east by 29th Street. The location of the ballpark was not far from downtown Philadelphia. The grandstand and home plate were located in the southwest corner of the park site. This park site, although consisting of the entirety of one city block, was not large: 400 (east-west) by 455 feet (north-south) and amounted to 4.2 acres. By comparison, other wooden Deadball Era major league ballparks occupied sites ranging from 3.9 acres (League Park III in Cleveland) to 9.6 acres (American League Park in New York). The 400 foot (east-west) dimension, along Oxford Street on the south and Columbia Avenue on the north, limited the extent of the ballpark’s right field dimension.

For Opening Day 1901, the ballpark’s seating areas consisted of a single-deck covered grandstand that extended from first base to third base, and sets of bleachers down both foul lines. Behind home plate, there was a short diagonal section of the grandstand that formed the backstop. On the roof of the grandstand were both a small press box and a wire screen on each side of the press box to try to keep foul balls from leaving the ballpark. There were short gaps between the grandstand and both sets of foul line bleachers. Both the first base and third base bleachers ran parallel to the foul lines—thus creating an ample amount of foul territory. The first base bleachers reached nearly to the right field corner, and the third base bleachers extended all the way to the left field perimeter fence on Columbia Avenue and then hooked around as far as the left field foul line to face home plate. There was a wire screen erected on top of the right field perimeter wall that was intended to keep home runs and foul balls from hitting vehicles in and possible pedestrians along 29th Street.

As home plate was in the southwest corner of the park site, the left field line ran due north-south, and right field was thus the sun field for afternoon games. There was a modest-sized scoreboard in right-center field that was set into the right field-center field fence. There was one small clubhouse (for the use of only the home team), but no dugouts—the players sat on benches in front of the grandstand. On Opening Day 1901, Columbia Park had seating for 5,000 in the grandstand, and 4,500 in the bleachers, for a total of 9,500. Capacity was expanded by a small amount in 1903 by adding seats to the foul area first base bleachers.1 Additional unspecified foul area expansion raised the seating capacity to 13,600 for the 1905 season. In the Deadball Era, capacity was an elastic concept. The all-time record attendance at Columbia Park—for a crucial game against the White Sox late in the 1905 season when 25,187 were in attendance—was far in excess of the park’s seating capacity of 13,600.

The A’s won two American League pennants playing at Columbia Park, but hosted only one World Series, in 1905 against the New York Giants. The A’s other pennant was in 1902, a year before the American and National Leagues agreed to a post-season series. Columbia Park was also used by the National League Phillies for 16 games in 1903 while the Phillies home park (National League Park, later known as Baker Bowl) was temporarily under repairs after a portion of the stands tragically collapsed.

Columbia Park was abandoned after the 1908 season when the A’s moved into the first of the Classic ballparks—Shibe Park. When the A’s left, the park was used by a circus and for other events for several years before being demolished. The site is now a mixed commercial and residential area.

The Basis of Columbia Park’s Configurations and Dimensions

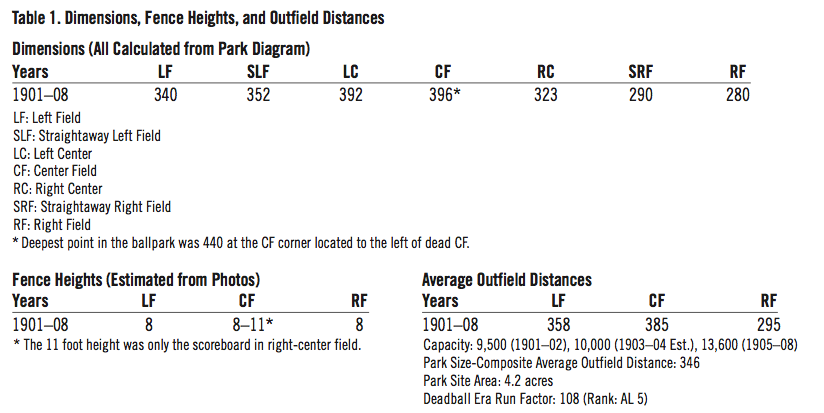

No listed dimensions for Columbia Park were found in any of the usual ballpark reference books.2,3 The 1901 dimensions: LF 340, CF 396, RF 280 (all dimensions are in feet), were derived entirely from a finely-detailed 1907 Philadelphia City Atlas.4 This atlas provided the size of the park site, and the location and extent of the grandstand and bleachers. The foul lines were not shown. A diagram of the park and the dimensions of the park site were copied from the 1907 atlas. The details that were copied from the atlas included the location of the grandstand, bleachers, and the main entrance to the ballpark (located at the corner of 30th Street and Oxford Street). The location of home plate was based on photos of the park, and was estimated to have been 72 feet from the diagonal section of the grandstand that formed the backstop. Given the location of home plate, all of the outfield dimensions were then calculated from the park diagram. Because the shape of the land plat was a rectangle and the foul lines were parallel to 29th Street, the outfield fences were aligned at 90 degrees to the foul lines in both left field and right field. Based on research into home runs at Columbia Park, it was found that there had been home runs hit over an interior fence in right field and right-center.5 From the 1901 Opening Day photo in the Philadelphia Inquirer, this interior fence was quite close to the perimeter right-field wall and screen and included a modest sized scoreboard in right-center.6 The right field screen was constructed of chicken wire and was an estimated 25 feet in height. The screen was mounted on top of the perimeter right-field wall. This screen, as it was erected on the exterior wall, located behind the interior fence, was out-of-play and extended all the way to the center-field corner.

In summary, all of the Columbia Park dimensions were estimated from the 1907 Philadelphia City Atlas. As neither the foul lines nor the home plate locations were shown in the atlas, these dimensions contain a small amount of uncertainty. All dimensions were checked against, and are consistent with, the available photographic evidence and the home run data. Park data and dimensions for Columbia Park are shown in Table 1.

(Click image to enlarge.)

The Impact of the Park’s Configuration and Dimensions on Batting

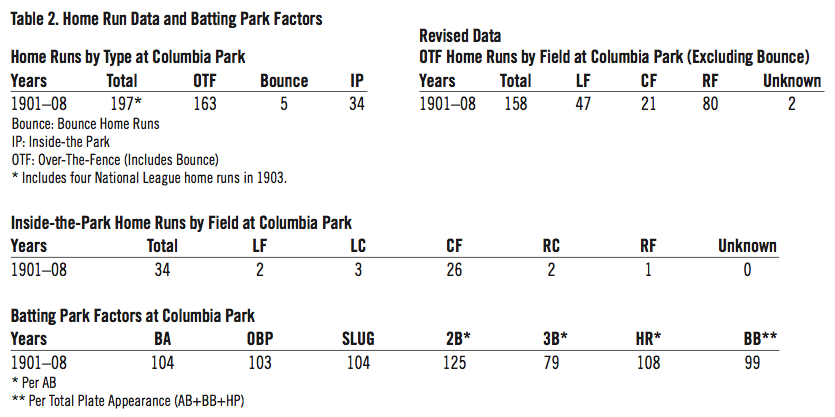

Columbia Park, in its limited lifetime of eight American League seasons (1901–08), was the smallest ballpark in the American League. Over the ballpark’s eight major league seasons, Columbia Park was above average for batting average, on-base percentage, slugging percentage, and doubles. (See table below of Batting Park Factors.) In the 1902 season, the A’s compiled a .322 home batting average (highest in the American League) at Columbia Park, while hitting only .249 on the road. This 73-point difference was the largest home/road differential in batting average for any team in the Deadball Era.

(Click image to enlarge.)

As the smallest American League ballpark, Columbia Park was a poor park for triples and inside-the-park home runs (IPHRs). There were only 4.25 IPHRs per season at Columbia Park while the average American League ballpark had more than twice that number per year in the 1901–08 seasons. At Columbia Park, the large majority of IPHRs were hit to CF, as that was the only deep part of the ballpark. Bounce home runs were rare–less than one per season because (1) the stands were not close to the foul lines (except in deep left field), and (2) the outfield fences were a minimum of eight feet in height. Of the five bounce home runs hit at Columbia Park, four were into the foul area third-base bleachers and one bounced over the interior fence in fair right field. The distribution of over-the-fence (OTF) home runs reflected the outfield dimensions. Left field (340 feet) had 47 OTF home runs, while right field (280 feet) had 80 OTF home runs. The batting Park Factor for home runs during the eight-year life of Columbia Park was only 108, a surprisingly modest value for the smallest ballpark in the American League and one with a composite average outfield distance of only 346 feet. This result occurred because while OTF home runs were relatively numerous with this small park size, there were not many IPHRs. Throughout the Deadball Era, and especially before the introduction of the cork-center ball, there was no relationship between park size and home runs.

RON SELTER is a retired economist, formerly with the Air Force Space Program. He is a member of the Ballparks, Minor League, Statistical, and Deadball Committees, and his area of expertise is twentieth-century major-league ballparks. Selter served as text editor for “Green Cathedrals” (2006 edition, SABR) and as a contributor to “Forbes Field” (2007). He is the author of “Ballparks of the Deadball Era” (2008).