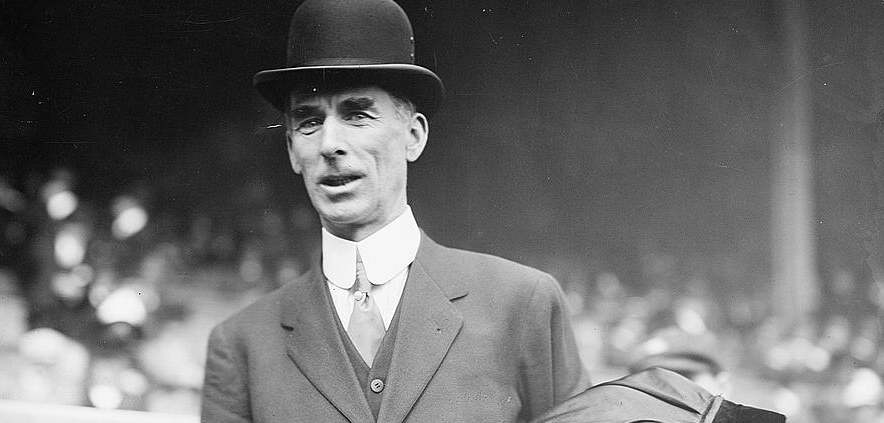

Connie Mack and Wartime Baseball — 1943

This article was written by Norman Macht

This article was published in The National Pastime: From Swampoodle to South Philly (Philadelphia, 2013)

Gerry Nugent and the Phillies were flat broke. Worse than that: They were concave broke. Not only were they penniless, they were in debt to the National League. NL president Ford Frick went looking for somebody to rescue the franchise. Bob Paul, sports editor of the Philadelphia Daily News, was approached by local sports promoter and professional basketball pioneer Eddie Gottlieb, acting on behalf of Leon Levy, president of WCAU and one of the backers of the new CBS network.

This is Paul’s story.

***

Gottlieb came to me and asked a favor: “I understand the Phillies are for sale. I want you to find out if they can be sold to a Jewish person. The owner of WCAU wants to buy the club but he’s been told that because he’s Jewish he didn’t have a chance. The only person that can answer that question is Ford Frick. As a sportswriter you can ask questions that we can’t. I’d like you to ask him.”

I said, “What’s in it for you?”

He said, “I would be general manager. We would have enough money to have a winning club.”

I called Frick and put the question to him: “Will the National League or baseball accept a Jewish owner?”

He said, “Of course I wouldn’t say to you they won’t accept a Jewish owner. I would never say a thing like that. I cannot tell Nugent what to do with his ballclub. I’m not going to tell Nugent to talk to that man or listen to him or take his money. The answer to your question is yes, a Jewish man can buy a ball club.”

I relayed that answer to Gottlieb. It turned out that his group said that wasn’t a definite enough answer. They were not going to be put in the spot of having their religion being the main issue in buying a ballclub. They wouldn’t go to Nugent unless Frick assured them they would be accepted if their finances were in order.

So they didn’t buy the Phillies.

***

In February Frick found a buyer in William D. Cox, a New York lumberman. That would lead to monumental consequences for the Athletics.

The autumn of 1942 was not a pleasant time for Connie Mack. It began in the clubhouse after the team’s closing doubleheader on September 20 (for some reason the A’s season finished a week earlier than the rest of the league). Bob Johnson’s contract had called for a bonus of $2,500 if attendance reached 400,000 and another $2,500 if it reached 450,000. While packing up his gear to head for Tacoma, Johnson, who had received the first bonus check, asked about the second one. Mack said there wouldn’t be a second check; they hadn’t come close to 450,000. Johnson didn’t believe him. According to Stan Baumgartner, “Hot words passed between them. The fine feelings of ten years were smashed in five minutes.”

Johnson may have been so adamant because of the evidence of his eyes. Or perhaps he was keeping score at home, noting the reported attendance figures in the box scores. Despite its lowly position, the team had temporarily sparked the interest of the fans. In the last week of May, a Monday night game against Washington, Friday night and Saturday Memorial Day Weekend games against Boston, and a Sunday doubleheader with the Yankees drew over 85,000. The papers projected a total of 600,000 for the year, the highest in a decade and a record for a last-place team.

The official final count was 423,487, although an unofficial Retrosheet count of daily attendance as reported in the newspapers—sometimes using an obvious round-number estimate—adds up to 546,141. Attendance bonus clauses always specified “paid home attendance.” What was reported, however, was the turnstile count, which would have included servicemen, kids, and other non-paying pass holders, for whom the home team did not owe anything to the visiting club or the league.

The club’s books seem to support Mack. In the closest comparable year, 1940, official attendance was 432,145 for 59 home dates; admissions totaled $552,542 vs. $522,926 for 1942. Visiting clubs’ shares totaled $120,135 in 1940 vs. $118,616 in ’42. The league’s share of receipts: $21,607 in ’40 and $21,174 in ’42. Had the actual paid attendance exceeded 500,000, as it did in 1941, the amounts paid to visiting clubs and the league in 1942 would have been closer to the 1941 figures: $148,148 to visiting clubs and $26,455 to the league.

The war of words grew more heated through the winter. Mack had met his match in stubbornness. Johnson wrote to Mack asking to be traded “even if you pay me the second bonus.”

Mack replied, “I don’t owe him a second bonus and he knows it.”

When Johnson was put on the trading block, several clubs expressed interest. None of them had any players to spare and offered only cash, which Mack rejected. Clark Griffith won the raffle in exchange for infielder Jimmy Pofahl (who refused to leave his defense job, the A’s receiving $6,250 compensation) and Cuban outfielder Roberto Estallela.

Johnson was happy to be away from the left-field wolves at Shibe Park. “I never could understand why they booed me. I batted in over a hundred runs for seven straight years, but I was a bum when I struck out.”

But he was not happy about his part in the argument that had led to his departure. His respect for Mr. Mack was undiminished. The first time the Nationals and A’s met, Johnson walked across the field and shook hands with Mack. “Wasn’t that nice of Bob?” said Mack. “He didn’t have to do that.”

It was a bad deal for Connie Mack. Estallela could hit, but he turned easy fly balls into spectacular catches, and had no idea what to do with it after he caught it. Bobo Newsom, who had been with him in Washington, said, “Bobby’s a four-to-one shot to throw to the wrong base and if there were five bases instead of four, he’d be fiveto- one.”

To replace Johnson, Mack sent $5,000 and Dee Miles to Seattle for veteran outfielder Jo-Jo White, who had played for Mickey Cochrane on Detroit’s pennantwinning teams in ’34 and ’35.

In November Mack lost another longtime friend when George M. Cohan died. Mack and several other baseball men were honorary pallbearers at the funeral in New York.

***

Mack’s 80th birthday gala was postponed to February 5 to avoid the Christmas season. More than 850 civic, business, and baseball people turned out at the Bellevue- Stratford Hotel. He was lauded by old friends Clark Griffith, Bob Quinn, and Branch Rickey, among others. The speeches were of the kind usually heard at a funeral.

Quinn spoke of Mack’s generosity to the needy and to young men trying to go to college. “I know because I handled the money on many such occasions. And I want to add that Mr. Mack accorded me the same courtesy and consideration on our first meeting forty-seven years ago as he does now. That is one of the beacon lights of a great man.”

Rickey said, “I went to him with my first problems and he gave me sage counsel and encouraging advice. We don’t just admire Mr. Mack, we love him.”

Judge McDevitt quoted former A’s outfielder Walter French, who at a similar gathering a decade ago had said, “On December 23, 1862, our Lord created Connie Mack, was satisfied, and rested for the remainder of the day.”

Jack Kelly, Olympic oarsman and longtime friend, called him “an oasis of peace in a world torn by strife, a man of understanding in a world of misunderstanding.”

Mack was brighter of eye and keener of mind than many younger men at the gala as he rose near midnight and recounted his beginnings in baseball, touched on highlights of his career, and thanked the newspapermen for their support. Then, showing that he was still more forward-thinking than anyone else in the room, he suggested that selecting all-time all-star teams was obsolete. Citing the many changes the game had undergone over the years, he said, “There is only one fair way to select all-star teams and this is to choose one every ten or fifteen years and make only ten-year men eligible for such a club … If I were to have my way I would have the sportswriters of this country select such a club every ten years.”

***

Al Simmons had watched the caliber of pitching all last season and decided he could hit it. Besides, he had begun to brood over the fact that he was 103 hits shy of 3,000. That hadn’t meant much to him during his heyday—there were only six who had reached 3,000 at the time, and nobody made a big deal about it. But now, as he neared 40, he began to mentally kick himself for all the at-bats he had wasted in one of his peevish periods and the days off he had taken. He hadn’t batted once in 1942. When he told Mr. Mack he wanted to go back on the active list, Mack thought it was a bad idea to try to come back after a year off, especially at the age of 40. “But if you want to do this and can hook on with somebody else, you have your release. And when you’re ready to come back, your job will still be here.”

On February 3 Eddie Collins agreed to take him on the Red Sox. Simmons found his eyes and legs were as good as ever, but his reflexes weren’t. The wrist action required to get around on a fastball was gone. He collected 27 hits and batted .203. After the season he admitted it had been foolish. “No man worked harder or was in better physical condition for a comeback. But I couldn’t make the grade.“

Connie Mack had made a December trip to Savannah and a few spots in Florida in search of a new training site.

Then the government announced restrictions on travel that threw baseball for a loop. Commissioner Landis ordered all clubs to set up camp someplace close to home. All plans to head for their usual sunny climes went out the window. Teams arranged with private schools, colleges, resorts—anyplace that had some indoor facilities—for makeshift facilities. No club went farther than 450 miles from its home ballpark, and the Washington Nationals stayed home.

The Athletics went just 35 miles to Wilmington, Delaware. They stayed at the Hotel du Pont, three miles from the ballpark where their farm team played. Connie Mack walked to the park; most of the players went by bus. One cold day the players were waiting for the bus. Mack came out of the hotel and walked briskly by them, waving, and saying, “Come on boys, the walk will be good for all of us.”

Bobby Estalella asked the man next to him, “How old he?”

“Eighty.”

“He eighty?” Estalella said. “He live to be a hundred. We win the pennant, he live to two hundred.”

Estalella decided that if the old man could walk the three miles, he would, too.

The Athletics’ training camp was as much of a novelty to the local residents as it had been during the team’s first spring in California in 1940, especially to the youngsters in the small town. Charlie Lucas, 15, was one of them.

“Kids would come up to Mr. Mack for autographs,” Lucas recalled. “He was very patient and always obliged them. He sat in a box with Mr. Carpenter (Wilmington Blue Rocks co-owner with Mack) in a gray wool overcoat on cold days. Kids gathered around him and he would talk to them like a grandpa: ‘Are you playing ball in school … How’s your grades?’”

Was Connie Mack 50 years ahead of his time? Or do we just imagine that men were men and pitchers finished everything they started in those days? On March 27 he was quoted in the Washington Post, as saying, “Pitchers ought to get themselves in shape. Nobody should have to tell them to work every day, but dammit they want to take a day off now before they throw batting practice. And in a game if somebody hits a home run, they suddenly get an ingrown toenail and have to be taken out.”

Maybe he was just fed up with one complainer and let off some steam. Whatever. At 80, his fire clearly had not gone out.

Over the winter Mack watched more of his players go into the service, bringing the total to 20—by the end of the year it would be 29. Dick Fowler and Phil Marchildon reported for duty with the Canadian armed forces.

Mack’s daughter, Mary, had left the convent to marry Francis X. O’Reilly in 1932, and had separated from her husband in 1935. She had moved in with her parents in their apartment and was a social service worker at Temple University medical school when she decided to join the WACs and went off for motor corps training.

Connie Jr. went to work for Bendix Corporation, then the Third Service Command, while occasionally helping out Bob Schroeder in the A’s concessions business.

Mack’s grandson Connie McCambridge was attached to an engineers division from Michigan, waiting at Ft. Dix, New Jersey, to go overseas. When he asked for a pass to say goodbye to his grandfather, Connie Mack, two officers decided they had to go with him.

“They were all ice skaters,” McCambridge said, “and they wanted me to ask Dad if he could get them in to use the hockey arena. Dad picked up the phone and it was all set, just like that, and on a Saturday afternoon they went to play hockey and skate—all free—and I stayed in camp ’cause I had duty.”

Only 10 minor leagues opened for business, and all but one completed the season. When the draft age was raised to 38 and the list of departing big-league players grew longer, the key of all of baseball shifted from major to minor. Clubs were permitted up to 40 players on their reserve rosters, though none had that many. The A’s had 29. Except for four pitchers, Mack’s only major-league players were Suder, Siebert, Valo, Swift, and Wagner. After a few days of practice Roberto Estalella said to him, “Mr. Mack, you’re one of the greatest managers, but if you do something with these bums, you the greatest manager in whole world.”

Connie Mack knew full well what he had to work with. He didn’t need the garrulous, fun-loving, overweight Bobby Estallela to remind him. His thoughts may have resembled those of George Washington on first inspecting the rebel rabble he was asked to command, or the Duke of Wellington surveying his troops pressed into His majesty’s service: “I don’t know what effect these men will have upon the enemy, but, by God, they terrify me.”

Mack had bought pitcher Jesse Flores, listed at 24, really 28, on a trial basis from Los Angeles for $1,000 in September. Flores had been 14–5 with the Angels. Mack liked what he saw and paid the $9,000 balance on April 27. Flores was a heady pitcher, threw several pitches including the most effective screwball in the league, and was sneaky fast. Midway through the season he added a knuckleball. He pitched 230 innings and was 12–14 with the only ERA on the staff lower than the league average.

Don Black was another old-for-a-rookie pitcher at 26. Mack paid $5,000 for him after he’d won 18 for Petersburg in the Class C Virginia League. Black worked over 200 innings for a 6–16 record.

Under a working agreement with Williamsport, Mack had his pick of up to three players. He had taken just one, 24-year-old infielder Irv Hall, who had spent six undistinguished years in the lower minors. The 5-foot- 10, 150-pound Baltimore resident was tickled to death to be in a major-league spring training camp. Strictly a singles hitter, he not only became the everyday shortstop, he survived the return of the servicemen and lasted until 1947 (although baseball.reference.com says his last game in MLB was in 1946).

When Hall signed his 1943 contract for $2,500, he told Mack, “My father wants to be a farmer and I want to borrow $1,800 to buy a farm for him.”

Mack agreed, “We’ll take so much out of your salary until you pay it back.”

At the end of the year there was still $600 due. Mack called Hall to his office, cancelled the rest of the debt, gave him a $1,200 bonus, and a ’44 contract for $4,000.

With an eye as much on draft status as ability, Mack had drafted two men with enough big-league experience to demonstrate they were not big-league caliber: 29-yearold outfielder John Welaj from Buffalo, and 33-year-old infielder Eddie Mayo from Los Angeles. But they hustled, gave it all they had, and never complained, grateful to be back in the bigs. Mayo won the third-base job, but in a spring game a throw ricocheted and hit him in the left eye, which developed a blind spot. He said nothing, but dealt with it and batted .219. During the winter Mayo’s eye cleared up. The Tigers picked him up and he had five productive years with them, including a second-place finish in the 1945 AL MVP voting.

(Twenty-seven years later, Mayo attended a ceremony dedicating a monument in front of Connie Mack’s birthplace in East Brookfield, Massachusetts. At a dinner that followed, Mayo said, “I once asked (Mr. Mack) about what was the hardest thing in managing a ball club, expecting he would answer about strategy or player relations. ‘Telling a player you have to release him,’ said. Mr. Mack. It was a classic remark and a lesson that has helped me greatly in my business career.”)

Like many who played for Mack, what John Welaj remembered most was what he learned from sitting beside him on the bench. “I heard him tell pitchers how to pitch to certain batters, and hitters what to do at the plate in certain situations. And, of course, his moving the outfielders.”

But now there was less of that moving the outfielders than there had been in the past. “You need real pitching to move your men around,” Mack said. “You’ve got to know that your pitcher knows where and how he’s going to throw the ball … But my pitching now is so uncertain it’s not worthwhile to try and play that style.”

Connie Mack still promulgated the illusion that Earle would succeed him, with a cryptic qualification. He told reporters on May 11, “Earle is going to be the next manager of the Athletics, if they ever have one, and he’ll probably do a better job than his dad.”

The A’s opened in Washington in a wartime atmosphere that prevented President Roosevelt from being there. War Manpower chief Paul McNutt, whose ballplaying days went as far as Indiana University, filled in for him. Before the first pitch, Clark Griffith walked toward the A’s bench and gestured for Connie Mack to come over to the VIP box. Mr. Mack’s emergence from the dugout evoked a standing ovation from the 25.000, and he ate it up. He took off his hat and clasped his hands above his head grinning broadly as he strode rapidly across the field. On his way back he waved to the fans in the bleachers.

The war affected the game in another way besides the loss of players. There was a shortage of rubber for wrapping the core of the baseballs, so Spalding experimented with something called balata, which was similar to golf ball cover material. The result was a dead ball. The balata balls were identified with a star, and were used only until May 9, when synthetic rubber replaced it. The balata balls resulted in Mr. Mack’s being accused of cheating.

The A’s were in third place, only two games behind the Yankees, when Detroit came to town for a doubleheader. Hal Newhouser shut out the A’s in the first game. Roger Wolff had a 4–2 lead in the top of the eighth of the second contest when Rudy York hit a long drive that looked like it was headed for the bleachers until it died like a plugged quail and was caught.

York and Tigers manager Steve O’Neill demanded to see the ball. It was one of the discontinued dead balata balls. O’Neill filed a protest with the league.

“Some old balls had come in from the factory along with the fresh supply,” Mack explained to Dan Daniel of the New York World-Telegram on June 11, “and if they got into the game the umpires were at fault.” The protest was rejected.

The A’s had no hitting or pitching. By July 4 they were in the cellar to stay. They lost 105 games, and were swept in 18 doubleheaders. The old baseball gallows humor set in: “Somebody’s always saying we got to have harmony on this team. When (are) we going to get that guy Harmony?”

In some ways they matched the futility of the 1916 A’s, Mack’s worst team, losers of 117. The ’43 version batted 10 points lower than the 1916 outfit, and were shut out 23 times. They finished 49 games behind the Yankees but only 20 games below seventh, half the gap of the 1916 team.

Through it all Connie Mack continued to ride the patched-together, antique railroad cars through the hot summer, and shivered in the cold wet spring, watching, missing nothing on the field, knowing this would not be his year—that there may never be another “his year”—but never surrendering hope.

On July 6 in Cleveland Mack demonstrated that his mind was still sharp. Oris Hockett led off and singled for Cleveland. Lou Boudreau walked. Roy Cullenbine sacrificed them to third and second, respectively. Ken Keltner hit back to the pitcher, Orie Arntzen, who threw to catcher Bob Swift. Hockett danced between third and home without drawing a throw while Keltner made it to second and Boudreau, head down, raced for third and arrived while Swift was chasing Hockett toward the base. Apparently thinking that Boudreau was entitled to third, Hockett kept on going into left field. Swift instinctively tagged Boudreau, who was standing on the bag, and caught up with Hockett. Third base umpire Joe Rue called Hockett out.

Two outs, men on second and third.

Mack called time and beckoned for the home plate umpire.

“Mr. Grieve,” he addressed Joe Rue, “don’t you think that, since Hockett had regained third base before Boudreau was tagged, Hockett was entitled to the base and Boudreau was tagged for the second out? Hockett was then tagged for the third out (or, under the rules, for going out of the basepath), making it a double play.”

Rue pondered that while the press box crowd and fans wondered what the discussion was about. “You’re right,” he said.

Red Smith commented, “Only Connie could get the play right and the umpire’s name wrong.”

A rookie, Hal Weafer, was the first-base umpire. A few innings later Bobby Estalella hit a groundball that an infielder picked up and threw wild past first. After crossing the bag, Estalella turned to the left and walked back. First baseman Mickey Rocco had recovered the ball and routinely tagged him. Weafer called Estalella out for turning to the left after crossing the bag. Connie Mack knew the umpire had blown the call; the old rules had required a turn to the right, but they had been changed to allow the base runner to turn either way with impunity as long as he didn’t make a break for second. But Mack said nothing at the time.

When he wanted an explanation for a controversial call, or, as some umpires put it, “to berate us about something,” Mack would sometimes send Earle out between innings to tell the umps, “Dad wants to know after the game why you made that call,” and the umpires would go over to the dugout after the game. This time, reported Red Smith, the wily Mack said to Weafer, “Ah, on that play at first, Estalella turned the wrong way, didn’t he?”

“No,” said Weafer, “I thought he made a break for second.”

“So,” wrote Smith, “he avoided the trap which Connie, two jumps ahead of everyone, was laying for him.”

The A’s wound up losing the game, 2–0. That evening Mack admitted he wasn’t all that smart. “If I had known we were going to lose, I would have kept quiet about that play at third and let them call it wrong. Then I could have protested the game and it would have had to be replayed.”

On August 8 Elmer Valo went into the army just as the Athletics were beginning a record-tying, 20-game losing streak, the last 17 mercifully on the road. They didn’t see themselves as that bad and, in fact, were in most of the games right up to the last out. Mack juggled the lineup like W.C. Fields but there wasn’t much to juggle; most of them were batting .220 to .240. Roger Wolff won the last game before the swan dive, 4–0 over New York on August 6. Eighteen days later, the A’s were in Chicago for a doubleheader, their fourth twin bill in four days. The White Sox scored two in the ninth to win the first game, 6–5. Between games Mack said to Wolff, “You can either set a record or break this string.” The A’s scored eight runs in the third and Wolff cruised to an 8–1 win.

Mack didn’t hesitate to use Wolff in relief, especially for Jesse Flores who tired in the late innings. Wolff ’s knuckler would get by a catcher, but Mack seemed to sense when it would be most effective. In a game in Boston, he sent Wolff in to pitch the ninth with an 8–7 lead. With two out and the tying run on base, Mack ordered Bobby Doerr intentionally walked, causing gasps of disbelief among the by-the-book grandstand managers for putting the winning run on base. The next batter was Babe Barna, who had played for Mack five years earlier. Mack didn’t believe Barna could hit a knuckleball. He was right.

***

During the season a variety of exhibition games were played to sell War Bonds: old-timers’ games, service teams playing major-league all-star clubs, doubleheaders involving three teams. On August 26 Mack was present at the Polo Grounds along with a group of old-timers including Babe Ruth, Eddie Collins, Honus Wagner, Tris Speaker, and Walter Johnson. As the oldsters fell down attempting to catch pop flies, and 64-year-old Roger Bresnahan tried to hold on to Johnson’s pitches while Ruth tried at length before finally hitting one into the upper deck in right field, Connie Mack “almost cried. I wanted to remember them as they were in their prime,” he told Stan Baumgartner.

The All-Star game played in Shibe Park on July 13 was the first one played at night. Dick Siebert was the only A’s representative. The Yankees had six men on the AL roster, but manager Joe McCarthy chose not to use any of them and still won, 5–3.

***

The story of Carl Scheib is illustrative of how Connie Mack dealt with young players at that time. In 1942 Scheib was a 15-year-old pitcher in Gratz, Pennsylvania, north of Philadelphia in the coal country. The town of 800 people was not on any scouts’ itinerary. But it was on a traveling salesman’s route. One day the salesman called on the general store in town and the woman behind the counter told him about the star pitcher for the local high school. The salesman saw him pitch and wrote to Connie Mack about him.

Next thing Scheib knew, he had a letter asking him to come to Philadelphia for a tryout.

On Saturday, August 29, his brother Paul, a catcher, drove him to Shibe Park. The game was rained out, but the rain had let up by the time they arrived.

“I had no glove or shoes or uniform,” Scheib said. “So they had to go around the clubhouse and collect them for me. I went down to the bullpen and all the coaches and big wheels were there. I threw to Earle Brucker and Mr. Mack said, ‘You hurry back next year as fast as you can.’

“I had two years to go in high school but didn’t finish. The only thing for me in Gratz was the farm or the coal mine so I left quick as I could. My dad was a coal miner and died at fifty-seven. The next year I quit school and became the regular batting-practice pitcher, traveled with the team, got into a few exhibition games. In August we had a four-week road trip. On the train coming home Mr. Mack said to me, ‘It’s time for you to pitch.’

“I said, ‘I’m ready.’”

The Yankees were in town for the Labor Day doubleheader. That morning Carl and his parents went up to Mr. Mack’s office. His dad, Oliver, signed the contract for $300 for the rest of the season. Mack gave him $500 for signing, and handed Oliver Scheib a check for $1,000.

“Now you go down to the clubhouse,” Mack told Carl, “and get a uniform with a shirt number so you can be identified.”

The A’s won the first game, 11–2. Earle Brucker, the bullpen coach, took Scheib to the ’pen for the second game. He was sitting beside Orie Arntzen, who was old enough to be his father. Scheib was amazed that an old man like Brucker could still crouch and warm up a pitcher; Brucker was 42.

The Yankees led, 5–2, when the A’s rallied for two runs in the last of the eighth. Johnny Welaj had pinch-hit for the starter, Don Black. Orie Arntzen started the ninth and quickly gave up a few hits and walks. Earle Mack emerged and rapped the Shibe Park wall by the dugout with his hand, the signal for Scheib to warm up. Carl started throwing. More Yankees scored. Earle went out to the mound.

“You’re in there,” Brucker told Carl.

The first man Scheib faced was Nick Etten, who tripled. Joe Gordon singled him home. Carl, called “Charlie” in the Times account, then retired Hemsley and Crosetti.

The Yankees won, 11–4.

At 16 years, 8 months, and 6 days, Carl Scheib became the youngest pitcher in American League history. He worked in five more games, pitching the last four innings of the season and taking the loss when Cleveland scored four runs in the top of the 12th to break a 4–4 tie.

***

Under the new management of William Cox and Bucky Harris, the Phillies had turned over almost the entire roster. The new faces brought out the crowds. Although the Phillies finished seventh, they won 22 more games than the year before. Attendance doubled, and they outdrew the Athletics, 466,975 to 376,735, for the first time in 23 years.

But the Athletics benefitted by it, too. The rental income from the Phillies almost doubled, to $57,997, which included back rent owed at the time of the sale of the club to Cox. With $37,000 from the NFL Eagles and $7,681 from two prize fights, and a payroll of only $131,952, the Athletics managed to show a profit of $17,697.

In the fall of 1943 Mack spent that much and more trolling in minor-league waters. Then the Macks went for a rest to Atlantic City, where Connie visited a military hospital and umpired a softball game for the walking wounded.

***

While termites were eating away the foundation of the Athletics from within, another turn of events ultimately contributed to bringing down the house of McGillicuddy. On November 23, 1943, Commissioner Landis banned Phils president Bill Cox from baseball for betting on games. Robert Carpenter Sr. of the du Pont dynasty, a minority stockholder, bought control of the team from Cox and installed his 28-year-old son, Bob Jr., as president.

“The closest I’d ever been to a major-league team was to watch a game from the stands,” Carpenter said. “It was all a new experience to me. I got a lot of help from Connie Mack. I would visit him in his office at Shibe Park and he was most gracious.” With millions at his disposal, Carpenter quickly hired Red Sox farm director Herb Pennock as his general manager and farm director while Carpenter was away for two years in the army. Majorleague rules forbade two clubs from sharing ownership of a minor-league club, so Connie Mack sold his interest in the Wilmington Blue Rocks to Carpenter.

The resurrection of the perennial National League doormats began, but the impact wasn’t felt immediately. The Phillies remained in last place during the war, then built a farm system and a pennant winner.

How the battle for survival in what was destined to become a one-team city would have turned out if William Cox had kept his nose clean and run a threadbare operation while the A’s became pennant contenders in 1948, or Connie Mack Jr. had bought out his brothers and competed with Bob Carpenter Jr. on an equally funded basis, must be left to the realm of the what ifs. The Athletics owned the ballpark. It would have been easier and more attractive for the tenants to move to the greener pastures beckoning in the west.

NORMAN MACHT hopes to complete the third and final volume of his Connie Mack biography before reaching the age at which Mr. Mack retired. He is considering calling it “My 66 Years in Researching Connie Mack.” His book “Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball” won the 2008 Larry Ritter Book Award and was a finalist for the Seymour Medal that year. His book “Connie Mack: The Turbulent and Triumphant Years, 1915-1931” was a finalist for the 2013 Seymour Medal.