Curse of the Billy Goat: An Adaptive Coping Strategy for Cubs Fans

This article was written by Jeremy Ashton Houska

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

Researchers in the social sciences who have investigated the effects of sports fandom acknowledge the positive impacts of team allegiances on psychological health.1 Classic studies in social psychology have demonstrated that fans will bask in the reflected glory of a winning team by making others aware of their affiliation with it2, or will, conversely, distance themselves from a losing team.3

Fans employ these processes of image enhancement and protection (Basking in Reflected Glory, or “BIRGing” and Cutting off Reflected Failure, or “CORFing”) in order to maintain their mood, self-esteem, and social capital.

Some research suggests that highly identified, or “die-hard,” fans engage in these strategies more frequently than less identified, casual fans4; other studies, however, find that CORFing is not an option for the staunchest fans.5

When their favorite team performs poorly, sports fans can maintain their psychological health by modifying their association with the team6. While the processes of associating and distancing from sports teams has been examined in a number of contexts, fewer studies have been conducted on fans’ beliefs in whether a team is somehow “cursed.” Moreover, belief in an external cause of failure is adaptive; belief in a curse can serve as a buffer against negative emotions associated with a team’s shortcomings.

Two of the most well-known sports curses have implicated the Boston Red Sox (“The Curse of the Bambino”) and the Chicago Cubs (“The Curse of the Billy Goat”)7. Beliefs in team curses are highly publicized in the media8, and fans even go to great (and disturbing) lengths in their attempts to reverse curses.9 Less understood, though, is the nature of these beliefs and the purposes they can serve for fans. Few researchers in sport psychology have studied beliefs in team curses; an exception is Daniel Wann and Len Zaichkowsky’s work on fans’ perceptions of the Red Sox curse.10

Wann and Zaichkowsky hypothesized that highly identified Red Sox fans would be more apt to utilize the Curse of the Bambino as a coping strategy than would less serious fans. Their rationale is that it is easier for fans to attribute a loss to a curse rather than blame players, the manager, or the front office for poor performance.

Data from Wann and Zaichkowsky’s (2009) study revealed three key trends. First, those fans who believed in luck and magic tended to believe in the Curse of the Bambino; second, those with a high sense of baseball fandom (regardless of beliefs in mysticism or team identification with the Red Sox) also reported increasing belief in the curse. Third, and most notably, the level of team identification accounted for the greatest variance in curse beliefs. That is to say, people who most strongly identified as Red Sox fans were most likely to believe in the Curse. Baseball fans will note that the Boston Red Sox’ 2004 World Series victory11 put an end to this curse.

The current study12 examined Cubs fans’ beliefs in the still-active Curse of the Billy Goat. In particular, this research addressed the possibility that sports curses serve a mood-enhancing function. Sports fans, one reasons, should be in a more positive mood if they can blame losses and poor performance on an outside force. It was hypothesized that highly identified Cubs fans presented with information about the Curse of the Billy Goat (i.e., the Curse Salience condition) would exhibit a less negative mood state than those highly identified fans who did not receive information about the Curse (i.e., No Curse condition).

This experiment employed a pre-test/post-test control group design. Participants were randomly assigned to a treatment group (Curse Salience condition) or a control group (No Curse condition) by the experimenter. Participants included 119 undergraduate students at Concordia University—Chicago (River Forest, IL), who took part in this study for psychology research credits or course extra credit. All participants went through the informed consent process and completed Peter Terry and colleagues’ (1999) Profile of Mood States for Adolescents (POMS-A).13

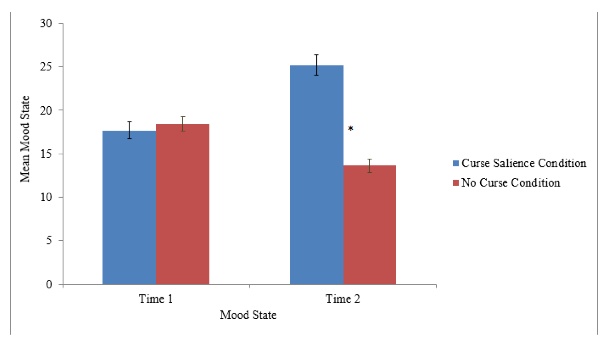

This initial assessment of participant mood with the POMS-A (“Time 1 Mood State”) was taken for two reasons. First, these pre-test data determined whether any of the participants’ moods were unusually positive or extremely negative. Extreme moods would affect subsequent stages of the study. No outliers were observed in the data.14 Second, these pre-test data determined whether systematic differences in mood existed between the two groups. The treatment group (Curse Salience) did not differ significantly from the control group (No Curse). See the Figure for a graphic depiction of the Time 1 Mood ratings. It was then concluded that any observed differences in mood at Time 2 could be attributed to conditions of the study.

Figure 1

Next, participants were presented an 18-item Baseball Fan Survey consisting of open-ended and Likert-type items on a seven-point scale (1 = strongly disagree, 7 = strongly agree). Survey subscales included Degree of Cubs Fandom (measured by number of years watching Major League Baseball and the Chicago Cubs, number of Cubs games viewed on television/ heard on radio, and number of Cubs players on one’s fantasy baseball team), and Identification with the Cubs items patterned after Daniel Wann and Nyla Branscombe’s Sport Spectator Identification Scale (1993)15 (e.g., “How strongly do you see yourself as a fan of the Chicago Cubs?” “I like the Chicago White Sox”). In addition, a Superstition subscale was created by adapting items from Tobacyk and Milford’s (1983) Paranormal Scale.16

Participants either received information about the Cubs’ performance that blamed the Curse of the Billy Goat (Curse Salience condition) or information that provided no mention of it (No Curse condition).

Key to this research study is that one experimental condition made the Curse of the Billy Goat salient to participants and the other did not. Participants randomly assigned to the Curse Salience condition read that the Curse of the Billy Goat explains why the Cubs have neither won a World Series since 1908 nor even played in one since 1945. Participants also read that this is the longest drought in Major League Baseball. The Cubs performance data were then presented for two time periods: from 1876–1945 and 1946–2009. The former period was emphasized as “Pre-Curse” and the latter “Post-Curse.” An additional sheet outlined the history of the curse, beginning with Billy Sianis and his goat Murphy’s ejection from Wrigley Field prior to Game 4 of the 1945 World Series. The Curse of the Billy Goat Timeline ended with the Cubs being swept by the Los Angeles Dodgers in the 2008 National League Division Series.

Participants in the No Curse condition also read information about the performance of the Cubs franchise. It was reported that the Cubs had not won a World Series since 1908 nor returned since 1945 and that these are the longest such droughts in Major League Baseball. Performance data were then presented for two time periods: from 1876–1945 and 1946–2009. There was no mention made of a Curse of the Billy Goat, or of such a curse’s history.

Immediately after reading the information in the Curse Salience or No Curse condition, participants completed Peter Terry and colleagues’ (1999) Profile of Mood States for Adolescents an additional time. This second assessment of participant mood (“Time 2 Mood State”) would test whether participants who read about the Curse would exhibit a more positive mood state than those who were presented Cubs performance data alone.

Finally, participants were given a full oral debriefing by the experimenter, had all their questions answered to their satisfaction, and left the laboratory.

Results revealed that higher levels of superstition were associated with stronger beliefs in the Curse of the Billy Goat. This finding is consistent with Wann and Zaichkowsky’s (2009) data on the Curse of the Bambino. It makes sense that people who believe in magic and mystical phenomena would also believe that Billy Sianis’ curse on the franchise has prevented the Cubs from returning to the postseason. Additionally, highly identified Cubs fans in the Curse Salience condition reported a less negative mood state relative to highly identified Cubs fans in the No Curse condition. This difference was statistically significant. See the Figure for a graphic depiction of the Time 2 Mood State.17 Because no statistically reliable differences in mood ratings existed between the groups at Time 1, there is greater confidence in the study conditions and interpretation of the results. It was concluded that this laboratory study effectively evoked frustration and disappointment within participants in the No Curse group and less negative emotions in participants in the Curse Salience group.

In sum, these findings on the Curse of the Billy Goat replicate past research conducted on the Curse of the Bambino18 and are consistent with the notion that sports curses are used as a coping strategy.19 These findings suggest that die-hard Cubs fans may point (either playfully or seriously) toward Billy Sianis and his goat after a heartbreaking loss instead of the club’s inconsistent pitching staff, anemic lineup, poor management, or just an untimely error. Research in the social psychology of sport reminds us that fans will not distance themselves from their beloved team for long.20 Instead, Cubs fans shift their causal attributions from the players, manager, and front office to a goat. And this strategy is adaptive.

JEREMY ASHTON HOUSKA, PH.D., is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at Centenary College in Hackettstown, New Jersey. An experimental psychologist, he conducts most of his research in the laboratory and within the realms of cognitive and social psychology. Houska roots for his hometown Dodgers but has built allegiances to the Cubs and Mets as a result of his relocations and his preference for NL baseball.

Sources

Aharon Bizman and Yoel Yinon, “Engaging in Distancing Tactics Among Sports Fans: Effects on Self-Esteem and Emotional Responses,” The Journal of Social Psychology 142 (2002): 381-392.

Gil Bogen, The Billy Goat Curse: Losing and Superstition in Cubs Baseball Since World War II (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009).

Ben Brumfield, “Curses! Goat’s Head Found at Wrigley Field” CNN.com, last modified April 11, 2013, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/11/justice/chicago-goat-curse/index.html

Robert B. Cialdini, Richard J. Borden, Avril Thorne, Marcus Randall Walker, Stephen Freeman, and Lloyd Reynolds Sloan, “Basking in Reflected Glory: Three (Football) Field Studies,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 34 (1976): 366-375.

Mike Dodd, “Finally! Red Sox win World Series,” USA Today, October 27, 2004.

Randy Roberts and Carson Cunningham, eds., Before the Curse: The Chicago Cubs’ Glory Years, 1870-1945 (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2012).

C.R. Snyder, MaryAnne Lassegard, and Carol E. Ford, “Distancing After Group Success and Failure: Basking in Reflected Glory and Cutting Off Reflected Failure,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (1986): 382-388.

Peter C. Terry, Andrew M. Lane, Helen J. Lane, and Lee Keohane, “Development and Validation of a Mood Measure for Adolescents,” Journal of Sports Sciences 17 (1999): 861-872.

Jerome Tobacyk and Gary Milford, “Belief in Paranormal Phenomena: Assessment Instrument Development and Implications for Personality Functioning,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44 (1983): 1029-1037.

Mark Van Selst and Pierre Jolicoeur, “A solution to the effect of sample size on outlier

Estimation,” The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, Section A: Human

Experimental Psychology 47 (1994): 631-650.

Daniel L. Wann, “Understanding the Positive Social Psychological Benefits of Sport Team Identification: The Team Identification-Social Psychological Health Model,” Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 10 (2006): 272-296

Daniel L. Wann and Nyla R. Branscombe, “Die-Hard and Fair-Weather Fans: Effects of Identification on BIRGing and CORFing Tendencies,” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 14 (1990): 103-117.

Daniel L. Wann and Nyla R. Branscombe, “Sports Fans: Measuring Degree of Identification with the Team,” International Journal of Sport Psychology 24 (1993): 1-17.

Daniel L. Wann, Merrill J. Melnick, Gordon W. Russell, and Dale G. Pease, Sport Fans: The Psychology and Social Impact of Spectators (New York, NY: Routledge).

Daniel L. Wann and Len Zaichkowsky, “Sport Team Identification and Belief in Team Curses: The Case of the Boston Red Sox and the Curse of the Bambino,” Journal of Sport Behavior 32 (2009): 489-502.

Angela Ware and Gregory S. Kowalski, “Sex Identification and the Love of Sports: BIRGing and CORFing Among Sports Fans,” Journal of Sport Behavior 35 (2012): 223-237.

Tom Weir, “What the ‘Hex’ is Going on?” USA Today, October 16, 2003.

Notes

1. Daniel L. Wann, “Understanding the Positive Social Psychological Benefits of Sport Team Identification: The Team Identification-Social Psychological Health Model,” Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 10 (2006): 272-296.

2. Robert B. Cialdini, Richard J. Borden, Avril Thorne, Marcus Randall Walker, Stephen Freeman, and Lloyd Reynolds Sloan, “Basking in Reflected Glory: Three (Football) Field Studies,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 34 (1976): 366-375.

3. C.R. Snyder, MaryAnne Lassegard, and Carol E. Ford, “Distancing After Group Success and Failure: Basking in Reflected Glory and Cutting Off Reflected Failure,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (1986): 382-388.

4. Angela Ware and Gregory S. Kowalski, “Sex Identification and the Love of Sports: BIRGing and CORFing Among Sports Fans,” Journal of Sport Behavior 35 (2012): 223-237.

5. Daniel L. Wann and Nyla R. Branscombe, “Die-Hard and Fair-Weather Fans: Effects of Identification on BIRGing and CORFing Tendencies,” Journal of Sport and Social Issues 14 (1990): 103-117.

6. Daniel L. Wann, Merrill J. Melnick, Gordon W. Russell, and Dale G. Pease, Sport Fans: The Psychology and Social Impact of Spectators (New York, NY: Routledge).

7. For more on the Curse of the Billy Goat, see Gil Bogen, The Billy Goat Curse: Losing and Superstition in Cubs Baseball Since World War II (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009), and Randy Roberts and Carson Cunningham, eds., Before the Curse: The Chicago Cubs’ Glory Years, 1870-1945 (Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press, 2012).

8. Tom Weir, “What the ‘Hex’ is Going on?” USA Today, October 16, 2003.

9. Ben Brumfield, “Curses! Goat’s Head Found at Wrigley Field” CNN.com, last modified April 11, 2013, http://www.cnn.com/2013/04/11/justice/chicago-goat-curse/index.html.

10. Daniel L. Wann and Len Zaichkowsky, “Sport Team Identification and Belief in Team Curses: The Case of the Boston Red Sox and the Curse of the Bambino,” Journal of Sport Behavior 32 (2009): 489-502.

11. Mike Dodd, “Finally! Red Sox win World Series,” USA Today, October 27, 2004.

12. Portions of this research were presented at the 83rd Annual Meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association, Chicago, Illinois, May 2011.

13. Peter C. Terry, Andrew M. Lane, Helen J. Lane, and Lee Keohane, “Development and Validation of a Mood Measure for Adolescents,” Journal of Sports Sciences 17 (1999): 861-872.

14. Van Selst and Jolicoeur’s (1994) z-score criterion for outlier exclusion was used.

15. Daniel L. Wann and Nyla R. Branscombe, “Sports Fans: Measuring Degree of Identification with the Team,” International Journal of Sport Psychology 24 (1993): 1-17.

16. Jerome Tobacyk and Gary Milford, “Belief in Paranormal Phenomena: Assessment Instrument Development and Implications for Personality Functioning,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 44 (1983): 1029-1037.

17. See the bar graph for a graphic depiction of mood states for participants in the Curse Salience and No Curse conditions.

18. Daniel L. Wann and Len Zaichkowsky, “Sport Team Identification and Belief in Team Curses: The Case of the Boston Red Sox and the Curse of the Bambino,” Journal of Sport Behavior 32 (2009): 489-502.

19. Daniel L. Wann, “Understanding the Positive Social Psychological Benefits of Sport Team Identification: The Team Identification-Social Psychological Health Model,” Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 10 (2006): 272-296

20. Aharon Bizman and Yoel Yinon, “Engaging in Distancing Tactics Among Sports Fans: Effects on Self-Esteem and Emotional Responses,” The Journal of Social Psychology 142 (2002): 381-392.