Eyeball to Eyeball, Bellybutton to Bellybutton: Inside The Dodger Way of Scouting

This article was written by Lee Lowenfish

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

A look at the Dodger way of scouting, tracing its roots back to Branch Rickey.

A look at the Dodger way of scouting, tracing its roots back to Branch Rickey. In the highly competitive, insular world of major league baseball, the phrase “The Dodger Way” still retains its hallowed place. The term can be traced to 1942, when Branch Rickey took over as general manager of the Brooklyn Dodgers and created a farm system that surpassed the one he built during his quarter-century with the St. Louis Cardinals. Though Rickey was bought out of Dodgers ownership by Walter O’Malley after the 1950 season, O’Malley understood the importance of scouting and player development. He retained experienced executives Buzzie Bavasi, Al Campanis, and Fresco Thompson, and The Dodger Way remained in force until Walter’s son Peter sold the team to Rupert Murdoch before the start of the 1998 season.

What was the secret that produced six pennants and one World Series winner in Brooklyn between 1947 and 1956 and nine more pennants and five World Championship flags in Los Angeles between 1959 and 1988? Al Campanis and Fresco Thompson both wrote about the club’s winning philosophy. In The Dodgers’ Way of Playing Baseball, an oft-republished nearly 300-page instructional book, Campanis explicated the organization’s belief in speed and agility and its meticulous attention to detail, everything from the way a player should wear his cap to how he should grip the baseball. Significantly, his discussion of pitching and fielding occupied more than the first half of the book.

(Left to right) Bobby Miske, Dick Teed, Buzz Bowers, Steve Lembo, Gil Bassetti and Bill Fesh.

In his entertaining, too-long out-of-print 1964 book Every Diamond Doesn’t Sparkle (David McKay, 1964), Thompson wrote, “Scouting can be distilled into a single sentence: the business of looking for new talent and looking at other people’s new and old talent.” Sounds so simple, doesn’t it? But the process of scouting and delivering sustainable major league talent can be devilishly hard.

Fred Claire, who served in the organization for 30 years and was the last O’Malley general manager, feels that continuity, consistency, and loyalty were the hallmarks of The Dodger Way. Claire says that during his tenure with the Dodgers never did the team go outside the organization to hire a pitching, batting, or third-base coach. Dodgers officials understood that the difficult game of baseball must be taught constantly, mistakes understood and corrected, and an optimistic attitude must always be displayed. In his insightful memoir My 30 Years in Dodger Blue (Sports Publishing, 2004), Claire gives credit to a college journalism professor who would not give a student an “A” grade in a feature writing class unless he handed in either three rejection slips or a published article. It was wonderful preparation for being an executive in a sport where missed opportunities are a daily way of life and those who succeed are the ones who know best how to bounce back from adversity.

Another feature of The Dodger Way was personal communication on all levels of the organization, “face to face and bellybutton to bellybutton,” in the vivid phrase of super scout Mel Didier (pronounced Did-ee-ay). Author of the absorbing memoir Podnuh, Let Me Tell You A Story (written with Texas sportswriter T. R. Sullivan, Gulf South Books, 2007), Didier is a man of many accomplishments. Named after fellow Louisianan, Hall of Famer Mel Ott, he is one of five brothers to have played professional baseball and is the father of former catcher and veteran minor league manager Bob Didier. Mel was also a great two-way football player for LSU, snapping the ball to future Hall of Fame quarterback Y.A. Tittle, and as a linebacker, throttling Charley Trippi in a classic trouncing of the University of Georgia. During his days as a football coach, Mel Didier picked the brain of the legendary coach Bear Bryant and brought Bryant’s uber-punctuality and use of tackling dummies into his baseball scouting and development work.

Another feature of The Dodger Way was personal communication on all levels of the organization, “face to face and bellybutton to bellybutton,” in the vivid phrase of super scout Mel Didier (pronounced Did-ee-ay). Author of the absorbing memoir Podnuh, Let Me Tell You A Story (written with Texas sportswriter T. R. Sullivan, Gulf South Books, 2007), Didier is a man of many accomplishments. Named after fellow Louisianan, Hall of Famer Mel Ott, he is one of five brothers to have played professional baseball and is the father of former catcher and veteran minor league manager Bob Didier. Mel was also a great two-way football player for LSU, snapping the ball to future Hall of Fame quarterback Y.A. Tittle, and as a linebacker, throttling Charley Trippi in a classic trouncing of the University of Georgia. During his days as a football coach, Mel Didier picked the brain of the legendary coach Bear Bryant and brought Bryant’s uber-punctuality and use of tackling dummies into his baseball scouting and development work.

Yet for all his achievements and innovations, Didier’s dream was to work side by side with Al Campanis. After the 1975 season his wish came true when he came to the Dodgers from the Montreal Expos, where he had been director of scouting for the expansion National League franchise and took great pride in the development of future Hall of Famers Gary Carter and Andre Dawson, who led the Expos into pennant contention.

Yet for all his achievements and innovations, Didier’s dream was to work side by side with Al Campanis. After the 1975 season his wish came true when he came to the Dodgers from the Montreal Expos, where he had been director of scouting for the expansion National League franchise and took great pride in the development of future Hall of Famers Gary Carter and Andre Dawson, who led the Expos into pennant contention.

Didier considers Al Campanis “the smartest baseball man I’ve ever been around. Arrogant, at times. A know-it-all at times. But, deep down, he had a great heart.” Didier never forgot Campanis’s advice: “Mel, if you ever find a guy who is strong in scouting and player development, you do anything you can to keep him and you pay him whatever you can because those guys are hard to find.”

Didier did not expect that his first tour of duty with the Dodgers would barely last a season, but another expansion team, the Seattle Mariners and their eager co-owner, entertainer Danny Kaye, beckoned him northward prior to the 1977 season to help the club get started. The scout was reluctant to leave his dream job, but given Walter O’Malley’s blessing and a promise that a Dodgers job would always await him, Didier headed to Seattle for what proved to be a disappointing tenure. He discovered that the ownership of the new organization lacked deep pockets and passionate Danny Kaye soon grew disenchanted and withdrew from an active role.

Didier did not expect that his first tour of duty with the Dodgers would barely last a season, but another expansion team, the Seattle Mariners and their eager co-owner, entertainer Danny Kaye, beckoned him northward prior to the 1977 season to help the club get started. The scout was reluctant to leave his dream job, but given Walter O’Malley’s blessing and a promise that a Dodgers job would always await him, Didier headed to Seattle for what proved to be a disappointing tenure. He discovered that the ownership of the new organization lacked deep pockets and passionate Danny Kaye soon grew disenchanted and withdrew from an active role.

Didier returned to the Dodgers after the 1982 season. Though he missed their 1981 World Series championship year, he played an important role advance scouting the Oakland A’s prior to the 1988 World Series. His report stressing that the A’s closer Dennis Eckersley always threw a backdoor slider on a 3–2 pitch went into Kirk Gibson’s memory bank, and the injured outfielder tapped the knowledge when he hit the dramatic home run in Game One of the Series that set the tone for Los Angeles’s five-game upset.

Didier also got to observe close-up the respectful if tumultuous relationship between Campanis and manager Tommy Lasorda, a Dodgers lifer who never succeeded in the major leagues as a pitcher and toiled many seasons as a scout and minor-league manager before he succeeded Walter Alston as Dodgers skipper. “[Campanis] used to really get on Tommy about his moves in the game,” Didier writes. “’Why did you do this? Why did you do that?’…He made Tommy Lasorda a better manager.”

It is one of the tragic ironies of Dodgers and baseball history that Al Campanis was not around to enjoy the 1988 championship. In April 1987, Campanis, who as an infield teammate in Montreal in 1946 taught the basics of second base play to rookie Jackie Robinson, told national TV interviewer Ted Koppel that African Americans lacked the “necessities” to work in the front office. Campanis was unaccustomed to being interviewed on television. His unwillingness to recant his remarks caused such an uproar that owner Peter O’Malley felt obliged to dismiss Campanis from his post as general manager and from the organization as a whole.

Campanis was thus not a part of the all-expenses-paid ten-day trip to Rome and the Italian Alps that Peter O’Malley awarded to all full-time Dodgers employees after the Series triumph. The festive excursion provided a storehouse of vivid memories for all who were in the traveling party. Bobby Miske, who spent 30 years as Dodgers area scout, remembers one overenthusiastic member of the Dodgers entourage who told everyone encountered that they were meeting the World Champions! When he spoke so loudly in the hallway before an audience with the Pope, a church official interrupted, saying sternly, “Ssssh! This is the Vatican.”

Left to right: the late Gil Bassetti, Dick Teed, Bobby Miske. Miske was inducted into the Scouts Hall of Fame, in Newburgh, New York, in July 2010.

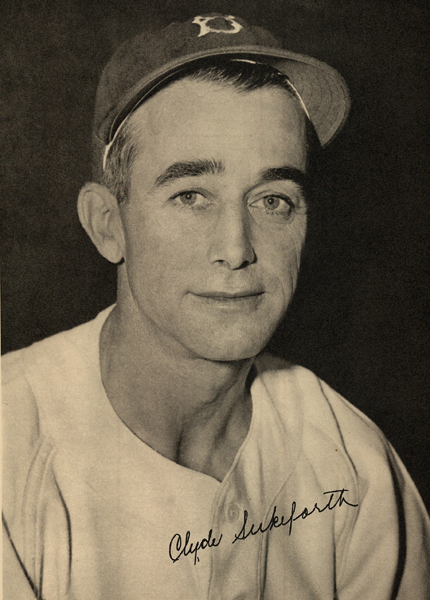

The Dodger Way of attentiveness to detail and convivial camaraderie extended to the grassroots of the organization. From 1977 through 1992 Dick Teed served as the Dodgers’ East Coast scouting supervisor. In conversation during the 2010 season Teed recalled warmly how the late Steve Lembo, one of his New York metropolitan-area scouts, used to open up his summer home in the Hudson Valley after the end of the minor league season for a joyous weekend with all the scouts and their wives and families. On Friday night everyone gathered to enjoy 20 Maine lobsters sent down by the legendary former Dodgers scout Clyde Sukeforth, the man who introduced Jackie Robinson to Branch Rickey.

On Saturday while the women went sightseeing and shopping, the men talked inside baseball, comparing notes on the long season, and enjoying their annual golf outing. A few scouts like Bobby Miske and the New England-based Buzz Bowers were once-a-year golfers. They left links excellence to the athletic Teed, who though retired as a pro scout stays active as a Little League first-base coach in western Connecticut, teaching the young ones how to hustle and be aggressive on the bases. After their afternoon of frolicking on the golf course, the men would join Steve’s wife Josephine Lembo, the daughter of a Brooklyn restaurateur, who always had an Italian spaghetti dinner awaiting them, and all enjoyed another fine evening of food, libations, and friendship.

Love of the game and a willingness to put behind them the disappointments of their playing careers was a common bond for these ivory hunters. Dick Teed and his late brother Bill had both been minor-league catchers in the talent-rich Brooklyn Dodgers organization. Bill never made the majors and Dick struck out in his only at-bat with the 1953 Brooklyn Dodgers before he was farmed out to a Dodgers minor league affiliate that needed an emergency receiver. “I never could stick in the majors because in those days even a backup had to hit over .250,” Teed recalls of an era when there were only 16 major league teams, and the minors were flooded with talented players who never received a chance to establish themselves in the big leagues.

Over two seasons in Brooklyn in 1950 and 1952 Steve Lembo collected only two hits in 11 at-bats. In 1951 he experienced his most notorious part in baseball history when he warmed up Ralph Branca in the bullpen before Branca’s fateful meeting with the Giants’ Bobby Thomson in the ninth inning of their third and final playoff game. Once he became a scout, Lembo took great solace in signing outfielder Tommy Davis, who won the 1962 National League batting title. (Had Davis not broken his leg sliding he may well have become another Dodgers Hall of Famer.) Lembo also inked another Brooklyn-bred product, southpaw John Franco, who went on to become an All-Star closer for the Mets.

The late Gil Bassetti, another member of the Teed-Lembo scouting brotherhood who was enshrined in 2005 in the Staten Island Yankees (Short Season Class A New York-Penn League) Scouts Wall of Fame, pitched seven seasons in the Giants chain, winning 21 games one year but never rising above Double A. When Bassetti turned to scouting, one of his prize signings was the Dodgers’ base-stealing second baseman Eric Young.

Buzz Bowers never got out of Triple A with the Phillies, but he shared a lifelong friendship with his fellow Michigan State Spartan, future Hall of Fame pitcher Robin Roberts. After his years working part-time with the Dodgers, in 1992 Bowers was named by retiring Red Sox scouting legend Bill Enos as his replacement as a New England area scout. Among the major leaguers he has since signed are utility player Lou Merloni and pitcher Carl Pavano, who bounced back from several injury-riddled seasons to become a Minnesota Twins mound mainstay in 2010. Bobby Miske never played pro baseball although he received an offer from the Kansas City Athletics after graduating from the University of Buffalo. He set out early in life to become both a baseball scout and a basketball referee, succeeding in both to the point where he has been enshrined in nine halls of fame in the combined sports. His latest honor came in the summer of 2010 when a Professional Baseball Scouts Hall of Fame (PBSHOF) plaque was unveiled at Dutchess County Stadium, home of the Class A Hudson Valley Renegades of the New York-Penn League.It is one of the four franchises owned by the Goldklang Group, a sports and entertainment organization that has been a leader in espousing the cause of scout recognition at its other ballparks in St. Paul, Minnesota, Charleston, South Carolina, and Fort Myers, Florida. (In 2008 Buzz Bowers was enshrined in the inaugural year of the Goldklang PBSHOF and in 2008 Dodgers southeastern area scout Lon Joyce was similarly honored.)

Miske was modest in his acceptance speech, saying that he was just another scout who passed on signing Mike Piazza (though the slugging catcher was hardly a prospect, not drafted until the 62nd round mainly as a favor to Tommy Lasorda who knew the Piazza family). Miske said that he hadn’t signed any major leaguers but did bring into baseball three players who became scouts. He added that three of his players became extras in the Robert Redford film adaptation of Bernard Malamud’s novel The Natural.

The scout was too self-effacing in his remarks. After leaving the Dodgers in the wake of a 1993 shakeup in the Northeast division that saw his and Gil Bassetti’s departure and the retirement of Dick Teed, he worked as a professional scout for the Yankees where his advance scouting of the Mets in 2000 played an important role in the team’s victory in the subway World Series. He moved on to the Mariners for the next eight years and has since returned to the Yankees’ pro scouting team.

Although there was an exodus of valued scouts like Mel Didier after the O’Malleys sold the team, Dodgers fans can take solace in knowledge that the organization retains an appreciation for the importance of good scouting and player development. Gary Nickels, the Dodgers’ Midwest scouting supervisor since 2003, has been appraising talent for almost 40 years and in 2009 was inducted into the Midwest Scouts Association Hall of Fame. He is also in the Mid Atlantic Scouts Association Hall of Fame. For most of the 1980s the youthful-looking Nickels served as the Cubs Midwest scouting supervisor, where he was instrumental in signing Joe Girardi. “I knew Girardi wanted to finish his engineering degree at Northwestern to keep a promise to his deceased mother,” Nickels remembered during an interview before the 2010 Professional Baseball Scouts Foundation dinner in Los Angeles. So the Cubs waited until Girardi’s senior year before drafting him in the 5th round and signing the current Yankees manager.

From 1991 through 1998 Nickels was the scouting director for the Baltimore Orioles, where he hired Logan White as an area scout. Today White is Dodgers assistant general manager in charge of scouting and, technically, Nickels’s boss, a change in circumstance that both men laugh about. In the search for talent and its fulfillment, the best scouts have always put aside petty matters of rank and prestige in the interests of developing players to their fullest. Though Nickels takes pride in his signing of southpaw Clayton Kershaw as does White for his role in the emergence of first baseman James Loney, they both embrace the larger picture of sustaining team development and constant contention.

Years ago when working for the Cubs, Nickels paused during a lull in a game and mused to Kevin Kerrane, author of still-the-best book on scouting, Dollar Sign on the Muscle, “Have you ever thought how much of America the old scouts have seen?”

At a time when the Cold War against the Soviet Union exerted a formidable influence on contemporary American politics, Nickels said, “I wish we had some Russians here tonight so they could see how deep the game goes in our society.” And, I might add, how precious and passionate are the scouts who sustain and grow what should always remain our national pastime.

LEE LOWENFISH, a member of SABR since 1976, won the 2008 Seymour Medal for his biography “Branch Rickey: Baseball’s Ferocious Gentleman” (University of Nebraska Press, hardback 2007; paperback 2009). He was deeply honored in January 2010 when the New York Professional Baseball Scouts Hot Stove League gave him the James Quigley Memorial Award for “baseball service.”

Acknowledgments

Special thanks to baseball scouts Billy Blitzer of the Cubs and John Tumminia of the White Sox for their help in arranging interviews for this article. And to the Goldklang Group and its indefatigable leaders Marv and Jeff Goldklang and Tyler Tumminia for their dedication to recognizing the vital profession of baseball scouting.

Sources

- Campanis, Al. The Dodgers’ Way of Playing Baseball with illustrations by Tex Blaisdell. New York: E.P. Dutton, 1954.

- Claire, Fred with Steve Springer. My 30 Years in Dodger Blue www.SportsPublishing LLC.com. 2004.

- Didier, Mel and T. R. Sullivan. Podnuh, Let Me Tell You a Story. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Gulf South Books, 2007.

- Kerrane, Kevin. Sports Illustrated. March 19, 1984.

- Thompson, Fresco with Cy Rice. Every Diamond Doesn’t Sparkle. New York: David McKay, 1964.