John Donaldson and Black Baseball in Minnesota

This article was written by Peter Gorton - Steven R. Hoffbeck

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in the North Star State (Minnesota, 2012)

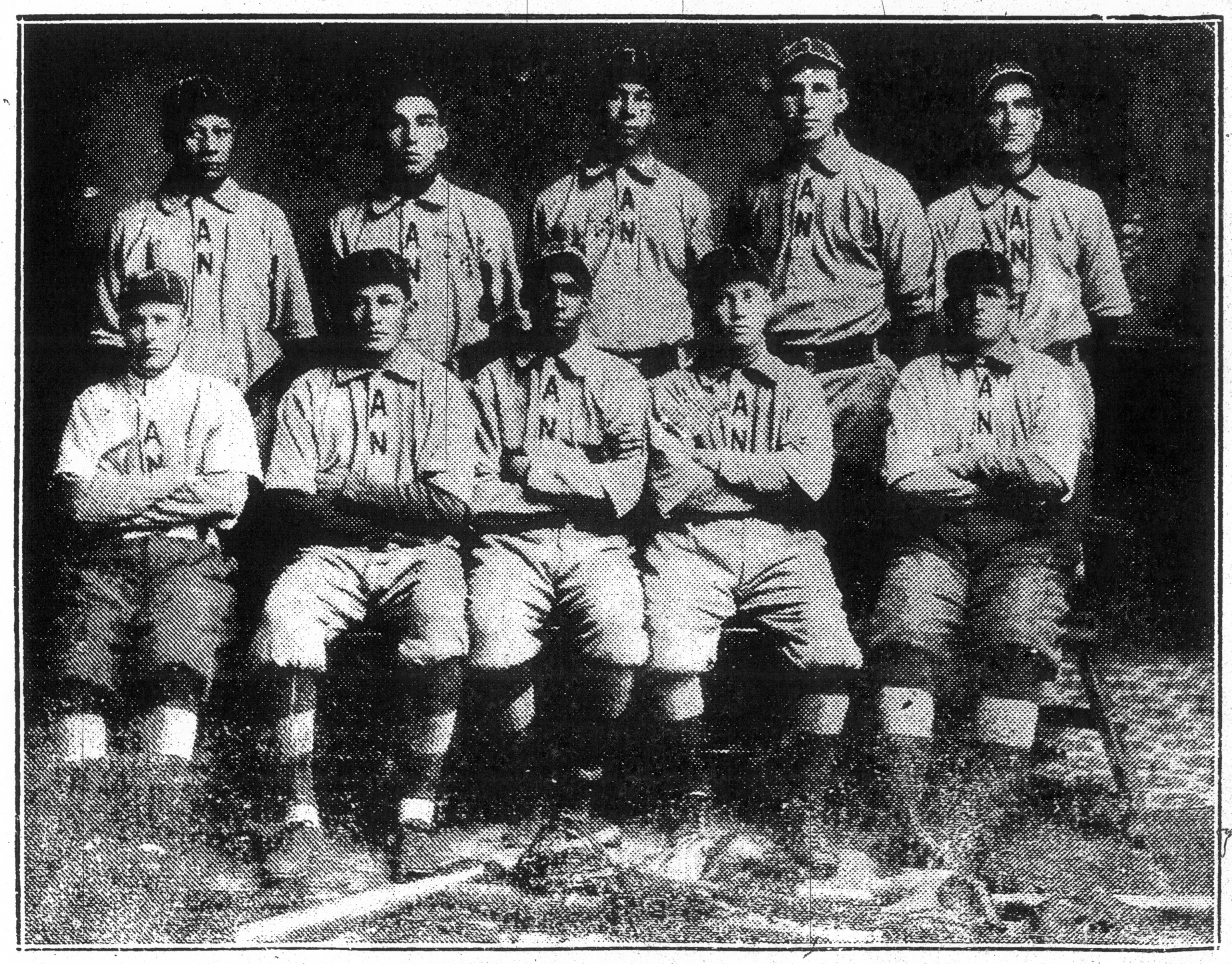

World’s All Nations, 1912, barnstorming club sponsored by the Hopkins Brothers sporting goods company of Des Moines, Iowa. John Donaldson, pitcher (front, third from right), was known as “The World’s Greatest Colored Pitcher” throughout his 30-plus years on the mound. After his playing career Donaldson was hired as the first Black scout in the major leagues. (AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

“The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color line.”—W.E.B. DuBois.1

For sixty years, professional baseball was as segregated as the Deep South. From 1887—when the unspoken national agreement prohibited African Americans from major league baseball—to 1947, when Jackie Robinson broke the color line, Black ballplayers were shut out of the highest levels of the White game.2 How could Black players, in Minnesota and in other states, respond to being banned from baseball? Well, they could have just given up and accepted segregation as grim reality. Or, young Black men could resolve to integrate the sport, town by town, city by city, one baseball diamond at a time. That’s what happened in Minnesota.

Renowned author Sinclair Lewis, a native Minnesotan, once said: “To understand America, it is merely necessary to understand Minnesota.”3 Let’s look at the state’s story.

In 1858, Minnesota joined the United States and its constitution declared that there would be no slavery in the state.4 In 1868, Minnesota extended voting rights to African Americans.

The Minnesota Constitutional Rights Law of 1899 prohibited discrimination in hotels, theaters and restaurants, and other public places, but such a law did not apply to professional baseball. Still, the Black population of Minnesota yearned for full social equality because they faced a haphazard maze of discrimination against their best efforts, a denial of rights and opportunities, of narrow-mindedness at best and unreasoning hatred at worst.

Minnesota’s Black ballplayers, therefore, worked to dismantle baseball’s color line themselves.

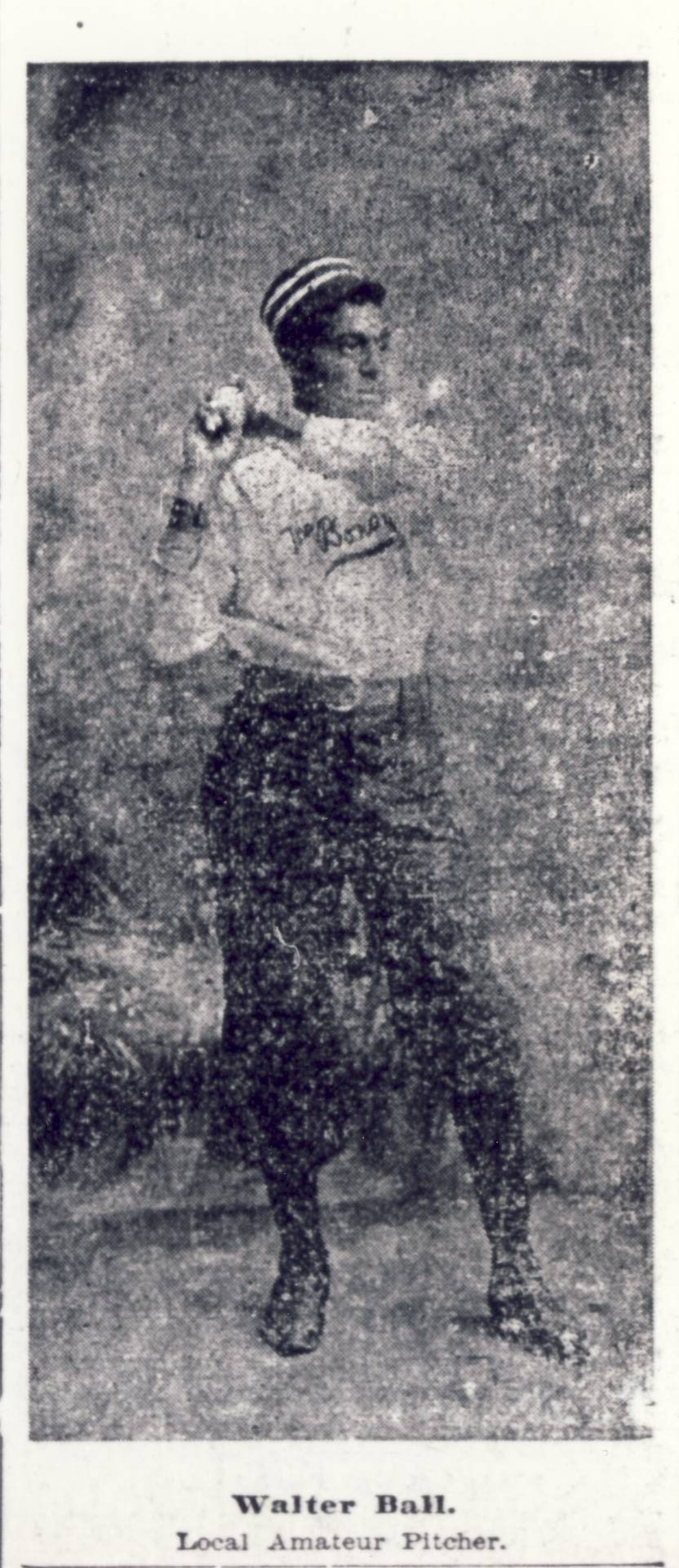

In the 1890s, pitcher Walter Ball integrated the St. Paul city public-school baseball teams and youth teams. In 1897, Ball and the Young Cyclones ballclub won the St. Paul City Amateur Championship—he was the lone Black player on an otherwise all-White team.5

Walter Ball (1880–1946), one of St. Paul’s best amateur pitchers in 1898, became a premier hurler among Minnesota semiprofessionals by 1902. In 1903 Ball moved to Chicago where he became one of the greatest pitchers in Black baseball through 1921. (ST. PAUL PIONEER PRESS / AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

After the turn of the century, Minnesota towns began to import some Black players for their formerly all-White teams. In 1900 the small-town Waseca ballclub secured Black pitchers George Wilson and Billy Holland—two men who had played for the best Chicago-area African American teams of the late 1890s. Waseca’s EACO Flour team brought the first Black ballplayers to the ball-diamonds of southern Minnesota, and they won the state semi-professional championship.6

In 1902, Walter Ball became the first Black player on St. Cloud’s formerly White semipro ballclub. Similarly, Billy Williams, also from St. Paul, integrated his high school team and other area teams.7

Minnesota’s own Bobby Marshall gained entry onto the Minneapolis Central High School baseball team in the late 1890s and then broke the color line on the University of Minnesota’s baseball squad in 1904.8

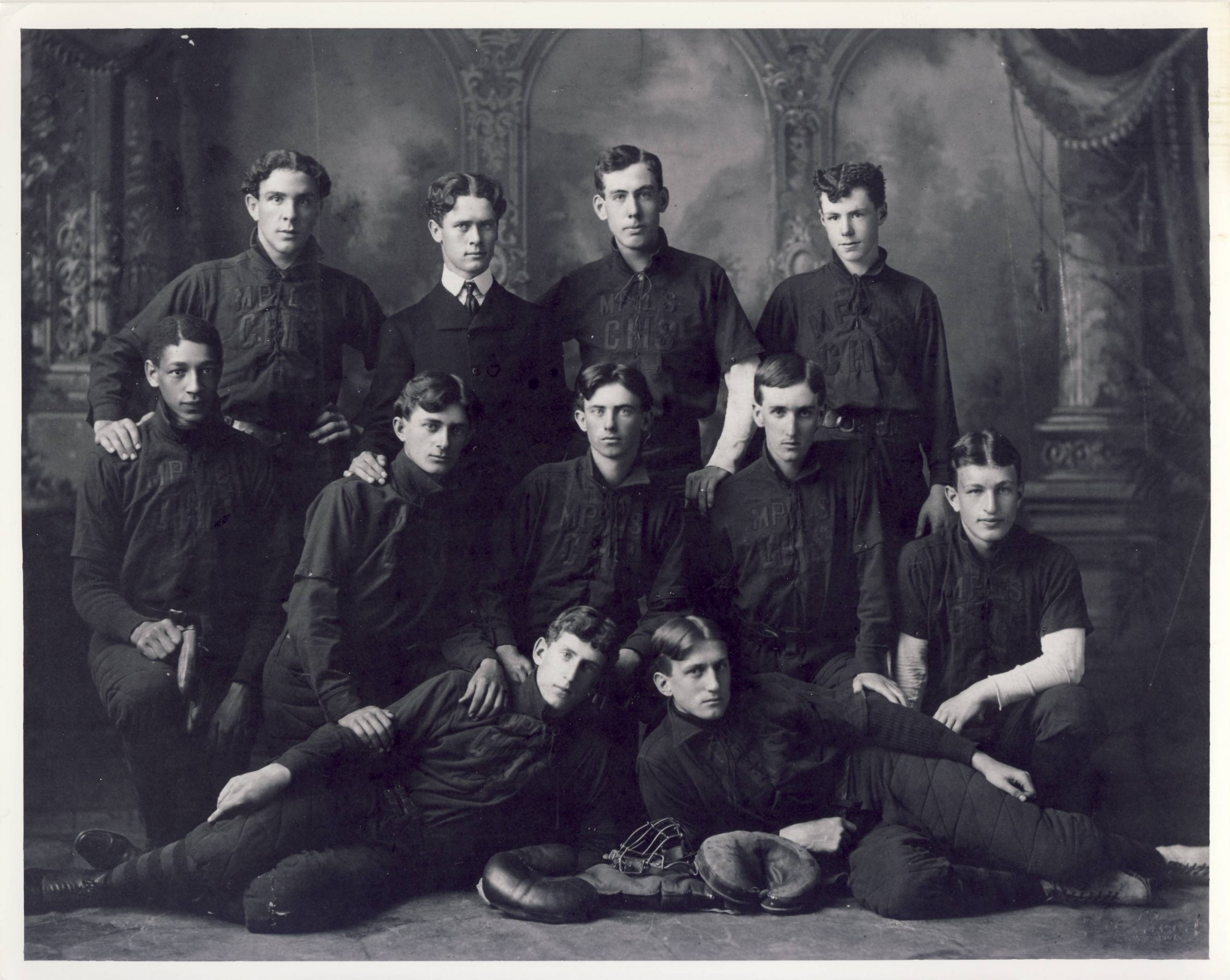

Black businessman Phil “Daddy” Reid established Minnesota’s first all-Black professional ball club, the St. Paul Colored Gophers, in 1907, gathering top talent from Chicago and elsewhere. Home-grown Bobby Marshall became the “star slugger” on the Colored Gophers team in 1909, when the Colored Gophers claimed the championship of Black baseball by defeating Rube Foster’s Chicago Leland Giants three games to two. The Colored Gophers barnstormed throughout the Upper Midwest for five years, 1907–1911, bringing a fast and colorful brand of Black baseball to towns that had never before seen an African American ballplayer on their local diamonds.9

Bobby Marshall (second row, left) integrated the 1900 Minneapolis Central High School baseball team and then broke the color line on the University of Minnesota nine. Marshall (1880–1958) played first base for the St. Paul Colored Gophers and other teams, and the multi-sport star became the first Black player in the National Football League (1920). (MINNEAPOLIS PUBLIC LIBRARY / AUTHOR’S COLLECTION)

The decade from 1910 to 1919 brought a new wave of Black barnstorming teams to Minnesota from other locales. Premiere among these was the All Nations ballclub, a multi-racial team founded in 1912 by James Leslie (J.L.) Wilkinson (1878–1964). Wilkinson was a genius in marketing and publicity, as well as a true baseball man. Although Wilkinson was White, he believed that baseball fans in Minnesota and throughout the Midwest would pay to see the very best and enthusiastically embrace the skills of a truly professional touring team brought in from the top ranks of Black baseball and a world that was learning to play America’s game.

The All Nations team in 1913 looked like the face of modern baseball with players coming from all over the world. It was composed of “men from all nations, including Chinese, Japanese, Cubans, Indians, Hawaiians…and the Great John Donaldson, the best colored pitcher in the United States today, also the famous [Jose] Mendez, the Cuban.”10 The All Nations squad competed against anyone who would play them—White semipro teams, regional all-star teams, and professional all-Black teams.

The key player on the team, John Donaldson (1891–1970), received top billing through 1918 and would spend many years barnstorming through Minnesota. Known as a power pitcher, Donaldson was lauded as “the “greatest colored pitcher” of the decade.11 Newspapers printed a quotation from New York Giants manager John McGraw: “If I could change the color of his skin I would give twenty thousand dollars for Donaldson and pennants would come easy.”12 When Donaldson fanned 29 batters in a 16-inning game, the St. Paul Pioneer Press judged the contest to have been “one of the best games ever played in the state.”13

Jose Mendez (1887–1928), dubbed Cuba’s “Black Diamond,” was the team’s second top star. He beat the Philadelphia Athletics in 1910, struck out Ty Cobb on three swinging strikes, and was labeled the “Black Mathewson” after subduing Christy Mathewson and the New York Giants in 1911 by throwing four innings of scoreless relief.14

Donaldson, Mendez, and the All Nations brought interracial baseball to a host of Minnesota’s cities, from International Falls in the north to Sleepy Eye and Blue Earth in the south. What began as a novelty ballclub quickly became a great team, and by 1916, the All Nations vied for supremacy among the best professional teams in America outside of major and minor league ball.15

In 1920, Rube Foster, supported by others, organized the eight-team Negro National League. John Donaldson, who had pitched so many times in Minnesota, rejoined Jose Mendez as a ballplayer on Wilkinson’s new Kansas City Monarchs team.

Minnesota had several all-Black teams in the 1920s, including the Askin and Marine Colored Red Sox and the Uptown Sanitary ballclub, but the state was not awarded a Negro League franchise. Racial attitudes seemed to harden in the Twenties as southern Blacks migrated north, Minnesotans began to fear Reds and foreigners, and the Ku Klux Klan stirred up hate in the “Jazz Age.” Donaldson again toured Minnesota in 1922–1923 because K.C. Monarchs owner Wilkinson needed barnstorming cash to prop up his franchise.

In the mid-1920s, as Rube Foster’s mental health deteriorated and disharmony between the Eastern Colored League and the Negro National League brought turmoil to Black baseball, John Donaldson jumped from the Monarchs back to Minnesota. By this time he had pitched almost everywhere in the nation, including a number of occasions on the national stage. He had battled Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants in 1916, and in 1918, Donaldson went head-to-head against the great Smokey Joe Williams of the New York Lincoln Giants.16

No longer a young man, John Donaldson accepted an offer to play semi-professional ball in Minnesota for the 1924 season, when he was 32 years old. He joined the Bertha Fishermen, a ballclub based in the small central Minnesota town of Bertha. Money was the chief reason—he was offered $325 per month, more than Negro Leaguers were making at the time. What’s more, Donaldson’s wife, Eleanor, was from the Twin Cities, and the couple could visit family members easily.17 In any case, when Donaldson led the squad to the Minnesota State Semi-Professional Championship in his first season, he brought instant statewide recognition to his new club.

Nineteen-twenty-seven was a momentous year. The major league season was spectacular: Babe Ruth, the magnificent slugging Bambino, set a home-run record with 60 circuit clouts. The New York Yankees, led by its “Murderer’s Row” of superstars— Earle Combs, Mark Koenig, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Bob Meusel and Tony Lazzeri—earned recognition as one of the greatest first six hitters in a lineup of all time.18

It was also the year that a Minnesotan, Charles Lindbergh Jr., made world headlines when he successfully crossed the Atlantic in a solo flight. Lindbergh’s hometown was Little Falls, a thriving community located along the Mississippi River, smack-dab in the central part of Minnesota, Accordingly, Little Falls gave its favorite son a true hero’s welcome-home event on August 25, 1927. The Lindbergh Homecoming Committee arranged for a morning parade, a noon baseball game between the House of David barnstorming ballclub and Bertha, an afternoon motorcade, and an evening banquet.19 Lindbergh was scheduled to arrive at 2:00 that afternoon, so the parade and baseball game were warm-up activities for the estimated crowd of fifty-thousand adoring Lindbergh fans.

The House of David ballclub amazed spectators with its dazzling skills. The bewhiskered ballplayers of this spiritual sect from Benton Harbor, Michigan, never knew a razor or scissors for beard or hair, but they knew baseball, having practiced their skills religiously. They had been touring the countryside since the 1910s and had a dominant reputation, although none of the men were Goliaths or Samsons in power.20

The Bertha Fishermen ballclub featured a Black battery of pitcher John Donaldson and catcher Sylvester “Hooks” Foreman. Foreman had been a mainstay with the Kansas City Monarchs and had a long-standing connection with Donaldson. The pitcher had faced the House of David previously, and his Bertha team had beaten the longhaired team by a score of 2–0.

Game day featured the morning parade through the streets of Little Falls, with bands playing, kids smiling, and dignitaries waving. Six thousand fans packed the grandstands and bleachers, while thousands more watched from behind wire fencing that surrounded the ballpark.21

At high noon the mayor of Little Falls, Austin Grimes, threw out the ceremonial first pitch and then handed the ball to Donaldson. The pitcher proceeded to throw two shutout innings, allowing no hits, and then switched to center field because he had thrown too many innings in his previous start.

Wisely, the management of Bertha’s ballclub had arranged for the mysterious Lefty Wilson as a “ringer” to lend assistance to Donaldson. The two knew each other well, having been opponents in Negro League games several years earlier.

Lefty Wilson was not his real name. He was a fugitive from justice, hiding in the hinterlands of Minnesota’s semipro ball and his real name was Dave Brown. Under his real name he had become famous as one of the best left-handed pitchers in the Negro League and a key player on Rube Foster’s Chicago American Giants from 1920 to 1922.

In 1923 Brown jumped ship, signing with the New York Lincoln Giants of the upstart Eastern Colored League. On May 1, 1925, Brown won a ballgame in New York, allowing just one run. After the game, however, policemen came to arrest Brown and two of his teammates for their involvement in a street brawl outside a nightclub in which one of the brawlers ended up dead. Brown fled from the ballpark that night and escaped from the city and a national manhunt.22

The authorities never found Brown. He had seemingly disappeared, slipping away into the deepest rural areas of southwestern Minnesota. There, amidst cornfields and cow pastures, Brown became “Lefty” Wilson, performing in ignominy in towns like Pipestone and Ivanhoe and Wanda. Donaldson, no doubt, assisted Bertha in securing Wilson from the Wanda team to pitch in the Lindbergh homecoming game.

In the game itself Wilson allowed only two hits to the House of David barnstormers, combining with Donaldson in a 1–0 shutout. Donaldson scored the game’s only run.23

As for Charles Lindbergh, he basked in the adulation of his fellow Minnesotans. The aviation hero landed the “Spirit of St. Louis” monoplane outside of town at about 2 p.m., and the townspeople paraded him through his old hometown.

Aviator Lindbergh had arrived after the ballgame had ended, and this perfectly symbolized a segregated America. Donaldson and Lefty Wilson were on the wrong side of the color line, toiling on the mound in relative obscurity. The international hero never saw them, and they likely caught little more than a glimpse of Lindbergh from afar. While the White Lindbergh was naturally feted for his historic flight, he clearly had opportunities unavailable to Black Americans. For Black men like Donaldson and Lefty Wilson, they could experience fame, but no matter how well they performed, their recognition would always be restricted by the limited nationwide interest in Black baseball.

After Lindbergh’s celebrated homecoming, Wilson pitched in Minnesota for several more years and then moved away, falling off the map and the historical record. Donaldson continued as he always had, pitching wherever he got the largest paycheck, a growing necessity as the twenties melted into the 1930s and the Great Depression.

The Negro Leagues crumpled into disarray after 1929 as the Depression clipped spending power, and the players scattered to cities where they could hope to earn a meager living playing ball. Barnstorming baseball teams continued to traverse Minnesota and the rest of the country, earning dimes and nickels for the players. The Chicago Defender claimed that the Black ballplayers who played for Minnesota teams in the later 1920s and into the 1930s earned the highest pay of any African American baseball stars in the nation. Donaldson stayed in the game, gathering former Negro League players in 1932 for his own team in Fairmont, Minnesota, calling it the Donaldson’s All-Stars.24

Minnesota finally got a Negro League team in 1942—the Minneapolis-St. Paul Gophers—although baseball historians don’t even bother to call it a franchise. The league they joined, the Negro Major Baseball League of America, was a flimsy patchwork that existed merely to provide opponents for the Cincinnati Clowns, which had been denied entry into the Negro American League.

After the Second World War, in 1946, Jackie Robinson broke the minor league color line in Montreal; a year later, under the tutelage of Branch Rickey, he broke the major league color barrier. Donaldson had retired from baseball in 1943 at age 52. With the integration of the sport, Donaldson finally joined major league ball in one of few capacities then open, becoming the first Black major league scout for the Chicago White Sox.25

Donaldson had begun his career in Missouri in 1908 and pitched just about everywhere over the next 35 years. Despite the many stops, Donaldson had a stellar reputation in knowledgeable baseball circles. Former Negro League ballplayers selected him as their first-team left-handed pitcher in the definitive 1952 Pittsburgh Courier newspaper poll. Modern research over the past decade has only enhanced that reputation. Intense combing of North American newspapers, both in newly-digitized and old microfilm versions, has shown that John Donaldson earned 413 wins in his career, the most by any left-handed pitcher in Black baseball history. Documented strikeout totals for Donaldson are equally impressive as he accumulated 5,081in his lifetime—again, the most strikeouts for an African American left-handed pitcher in all of baseball history.26 We consider John Donaldson the best left-handed barnstorming pitcher in Black baseball history.

It might be argued that the Black ballplayers from 1887 to 1947 sought to rectify social injustice by developing their individual talent, so that they would be a credit to the “Negro race.” This was the accomplishment of the “talented tenth” of Black Americans, as called forth by early civil rights leader W.E.B. DuBois—to rise and pull others up with them “to their vantage ground.” While the talent level was wildly uneven and the organization often chaotic, there can be little doubt that blackball hosted some of the finest individuals to ever play baseball.27

In 2006, Major League Baseball sought to correct some of the errors of the past when a select list of Negro League and pre-Negro League players, managers, and owners gained posthumous entry into the National Baseball Hall of Fame. Included in this group were two who had barnstormed through Minnesota: J.L. Wilkinson, the White owner of the All Nations (1912–1918) and the Kansas City Monarchs, who guided the Monarchs to become among the most successful franchises in Black baseball history, and Jose Mendez, whose early career in Cuba and his accomplishments with the Monarchs, including leading the team to three consecutive Negro League pennants (1923–25) as player-manager, gave him a reputation as a premier Black pitcher of his generation.28 Regrettably, John Donaldson was bypassed despite the support of Fay Vincent, the former baseball commissioner and chairman of the special election committee, who believed Donaldson would make the final list. Vincent had become well-versed regarding Donaldson’s reputation and statistics.29

The contributions of Black ballplayers in Minnesota are better known now because SABR researchers have worked together to document and preserve the history of Black baseball in the state since the 1970s. What is significant about this story is that Black baseball players in Minnesota, such as John Donaldson, Jose Mendez, Bobby Marshall, and Walter Ball, as a microcosm of baseball in America, played the national game in order to integrate baseball, and they succeeded, ultimately, in breaking the color line—one diamond at a time, team by team, town by town.

STEVE HOFFBECK is a Professor of History at Minnesota State University Moorhead and general editor/author of “Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota,” which won a Sporting News/SABR Baseball Research Award in 2005. Hoffbeck, his wife and his family reside in Barnesville, Minnesota.

PETE GORTON is the Presentation Services Coordinator for Faegre, Baker & Daniels, an international law firm based in Minneapolis. He is a former broadcast journalist who has written dozens of articles about John Donaldson, including a chapter in “Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota” (Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005). He is the founder of “The Donaldson Network,” a group of over 450 researchers, authors, and historians dedicated to the rediscovery of Donaldson’s baseball career. Gorton is the co-founder of johndonaldson.bravehost.com, a website detailing the career of “The Greatest Colored Pitcher in the World.” His efforts on behalf of Donaldson have been honored by SABR’s Negro Leagues Committee with the 2011 Tweed Webb Lifetime Achievement Award, recognizing long-term contributions to the field of Negro League and black baseball research. He resides in Northeast Minneapolis with his wife and two children.

Notes

1 “Worlds of Color,” Foreign Affairs 20, (April, 1925): 423, in Herbert Aptheker, Writings by W.E.B. DuBois in Periodicals Edited by Others (Millwood, NY: Kraus-Thomson Organization Limited, 1982), Vol. 2, 1910–1934, 241.

2 The color line was not fully entrenched in minor league baseball until 1895.

3 Sinclair Lewis, The Minnesota Stories of Sinclair Lewis (St. Paul: Borealis Books, 2005), 15.

4 “150 Years of Human Rights in Minnesota,” Minnesota Department of Human Rights, http://www.humanrights.state.mn.us/education/video/sesq.html, accessed on August 26, 2011.

5 St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 12, 1897, 7; Jim Karn, “Drawing the Color Line on Walter Ball, 1890–1908,” in Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 34–36.

6 Jim Karn, “Drawing the Color Line on Walter Ball, 1890–1908,” in Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota (St. Paul: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2005), 44–45.

7 Todd Peterson, Early Black Baseball In Minnesota (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2010), 10–13.

8 “Opening of the Baseball Season,” Minneapolis Tribune, April 7, 1900, 9; “Baseball at Varsity,” Minneapolis Tribune, April 3, 1904, 30; Steven R. Hoffbeck, “Bobby Marshall: Pioneering African-American Athlete,” Minnesota History (Winter 2004–2005), 159, 163.

9 Steven R. Hoffbeck, “Bobby Marshall, the Legendary First Baseman,” in Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota (St. Paul: MHS Press, 2005), 62–73.

10 Advertisement for All Nations in Blue Earth [MN] Post, September 2, 1913, 4.

11 Advertisement in LeMars [IA] Globe Post, May 22, 1913, n.p.; ad in Rock County [Luverne, MN] Herald, May 23, 1913, 11, col. 4.

12 “Marshall After Championship,” Marshall News Messenger, August 1, 1913, 1.

13 “Play a 16-Inning Game,”St. Paul Pioneer Press, August 25, 1913, 7.

14 “Cuban Nine Defeats Athletics,” New York Times, December 14, 1910, 14; “Joy In Cuba When Cobb Strikes Out,” New York Times, December 18, 1910, C6; “Bliss in Cuba,” Washington Post, December 23, 1910, 11.

15 Minneapolis Tribune, July 29, 1914, p. 12; Blue Earth Post, September 2, 1913, 4; Sleepy Eye Herald Dispatch, August 8, 1913, 4.

16 “All Nations Tackle the American Giants,” Chicago Defender, September 23, 1916, 25: “World’s Champions Break Even, Chicago Defender, October 7, 1916, 7; “Donaldson Again Bows,” Chicago Defender, July 13, 1918, 9.

17 Peter Gorton, “John Donaldson, a Great Mound Artist,” in Swinging for the Fences: Black Baseball in Minnesota, 2005.

18 “New York Yankees,” BaseballLibrary.com, http://www.baseballlibrary.com/teams/team.php?team=new_york_yankees, accessed on August 25, 2011.

19 “Colonel Lindbergh Home Thursday,” Little Falls Herald, August 19, 1927, 1.

20 “Bertha To Play House of David Team This Noon,” Little Falls Daily Transcript, August 25, 1927, 5; “Ball Team Keeps Beard Monopoly,” New York Times, May 24, 1934, 25.

21 “Bertha Wins, 1–0, From House of David Team,” Little Falls Daily Transcript, August 26, 1927, 5.

22 “Local Baseball Players Alleged to be Mixed in Shooting of Benj. Adair,” New York Age, May 2, 1925, 1.

23 “Bertha Wins, 1–0, From House of David Team,” Little Falls Daily Transcript, August 26, 1927, 5.

24 Highest pay extrapolated from “Webster McDonald Will Quit Baseball In 1936,” Chicago Defender, April 20, 1935, p. 17; from 1928 to 1932, McDonald was “the highest paid Race player in the country” when he played for the Little Falls, MN, White team.

25 “Chi Sox Sign Donaldson As Talent Scout,” Chicago Defender, July 9, 1949, p. 16; “Majors In New Search For Negro Ball Players,” Chicago Defender, July 9, 1949, 1.

26 John Donaldson statistics from http://johndonaldson.bravehost.com, accessed on August 29, 2011; Spahn and Johnson stats, Baseball Library.com, and BaseballReference.com.

27 Tim Marchman, “Squeeze Play,” Wall Street Journal, March 11, 2011, A13; W.E.B. Du Bois, “The Talented Tenth,” from The Negro Problem: A Series of Articles by Representative Negroes of To-day (New York, 1903), http://www.yale.edu/glc/archive/1148.htm, accessed on August 30, 2011.

28 “J. Leslie Wilkinson,” Hall of Fame plaque, National Baseball Hall of Fame, http://www.mlb.com/mlb/photogallery/hof_2006/year_2006/month_07/day_27/c…, accessed on August 25, 2006; “Jose Mendez,” Hall of Fame plaque, http://baseballhall.org/hof/mendez-jose, accessed on August 29, 2011.

29 Murray Chass, “A Special Election for Rediscovered Players,” New York Times, February 26, 2006, 8, 12.