The Legacy of the Players’ League: 1890 Chicago Pirates

This article was written by Gordon J. Gattie

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

During the late 1880s, professional baseball players became increasingly frustrated with the reserve clause, an outgrowth of the reserve rule established by National League (NL) owners in 1879. Arthur Soden, who served as a managing partner for the NL’s Boston Beaneaters, has been credited with creating the reserve rule. Soden and other NL owners argued that professional baseball would remain more stable, and thus more profitable, if franchises could maintain some stability in their rosters from year to year.

The reserve rule was originally a secret agreement among NL club owners affecting only five players; eventually, the formal reserve clause became part of the standard player’s contract. At first, some players enjoyed the security associated with a roster spot and corresponding salary over the intervening off-season, but the owners quickly realized the reserve rule could be used to limit player salaries in addition to player movement.

The reserve rule was originally a secret agreement among NL club owners affecting only five players; eventually, the formal reserve clause became part of the standard player’s contract. At first, some players enjoyed the security associated with a roster spot and corresponding salary over the intervening off-season, but the owners quickly realized the reserve rule could be used to limit player salaries in addition to player movement.

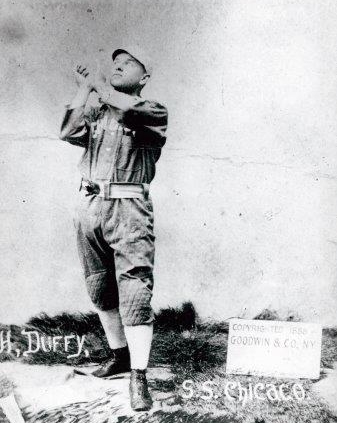

Several players took issue with owners limiting their rights. Led by star player and activist John Montgomery Ward, the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players formed in 1885. This organization led to the creation of the Players’ National League of Professional Base Ball Clubs (PL) for the 1890 season. The Chicago Pirates, the Windy City’s entry into the PL, featured key personnel such as right fielder Hugh Duffy, starting pitcher Mark Baldwin, and first baseman/manager Charles Comiskey.

Although the Chicago Pirates, and the PL, lasted only one season, the team and league significantly affected, among other things, the quality and quantity of players moving between leagues for three tumultuous years, baseball attendance, and the development of Charles Comiskey’s managerial style.

Ward helped found the Brotherhood of Professional Base Ball Players to address the owners’ unwillingness to better compensate players as the sport’s popularity increased. The goals of this first serious attempt at organizing professional ballplayers were to increase player salaries and abolish the reserve rule. A graduate of Columbia Law School, the erudite Ward penned the Brotherhood’s Manifesto, in which he compared the reserve clause with a fugitive slave law.

The Brotherhood Manifesto was issued on November 4, 1889, the same time that the NL distributed its contracts for the following season.1 In spite of growing protest, National League owners were still reluctant to work with the Brotherhood; in fact, in response, owners established a salary ceiling and began to charge players a fee for uniform rental. This final straw drove Brotherhood leaders Ward, Dan Brouthers, and Tim Keefe to turn away from the NL and create the Players’ League.

Offering higher salaries and improved working conditions, the PL—which received assistance from some NL star players and the American Federation of Labor—snared 56 players from the NL and quickly rose in stature above the American Association to directly rival the NL. The PL featured eight entries in its lone season: Boston, Brooklyn, Buffalo, Chicago, Cleveland, New York, Philadelphia, and Pittsburgh. Each PL entry competed directly with a National League counterpart, except for the Buffalo Bisons. Brooklyn and Philadelphia now had three professional teams, with representatives in the AA, the PL, and the NL.2

The Chicago Pirates played their home games at what is now known as South Side Park II, at 35th Street and South Wentworth Avenue.3 The fledgling Pirates fought with their NL counterparts, the Colts, for fans all season long. The Colts, formerly called the Chicago White Stockings from the NL’s inception in 1876, are now the Chicago Cubs.

The Pirates and Colts played their home games in different ballparks and had 48 conflicting dates out of 70 total home games.4 The Pirates ended the 1890 season in fourth place with a 75–62 record, and the club featured several statistical league leaders, including outfielder Hugh Duffy (161 runs, 191 hits), pitcher Mark Baldwin (33 wins, 53 complete games, 206 strikeouts), and pitcher Silver King (2.69 ERA).5 Table 1 shows the PL 1890 standings.

Table 1. 1890 Players’ League Standings6

| Team | Manager | GP | W | L | PCT | GB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston Reds | King Kelly | 130 | 81 | 48 | .628 | – |

| Brooklyn Ward’s Wonders | John Montgomery Ward | 133 | 76 | 56 | .576 | 6½ |

| New York Giants | Buck Ewing | 132 | 74 | 57 | .565 | 8 |

| Chicago Pirates | Charles Comiskey | 138 | 75 | 62 | .547 | 10 |

| Philadelphia Athletics | Charlie Buffinton, Jim Fogarty | 132 | 68 | 63 | .519 | 14 |

| Pittsburgh Burghers | Ned Hanlon | 128 | 60 | 68 | .469 | 20½ |

| Cleveland Infants | Henry Larkin, Patsy Tebeau | 131 | 55 | 75 | .423 | 26½ |

| Buffalo Bisons | Jack Rowe, Jay Faatz | 134 | 36 | 96 | .273 | 46½ |

The Boston Reds, led by future Hall of Famers King Kelly (manager and utilityman), first baseman Dan Brouthers, and pitcher Old Hoss Radbourn, won the pennant. Kelly was on the downside of his career, but still provided a strong gate attraction after coming over from the National League’s Boston Beaneaters. Dan Brouthers led the PL with a .466 OBA, finished third with a 4.4 offensive Wins Above Replacement (WAR), and finished fourth with 36 doubles. In addition to his baseball talents, Brouthers served as the vice president of the Players League Brotherhood Association7. Radbourn completed the season third in the PL with a 3.31 ERA, fourth in wins with 27, and in the top 10 in most pitching categories.

Notable batting leaders included Cleveland’s Pete Browning (.373) and Brooklyn’s Dave Orr (.371), the Giants’ Roger Connor (.998 OPS, 14 HR, 6.0 WAR), Harry Stovey from the Boston Reds (97 stolen bases), and the Reds’ Hardy Richardson (146 RBI). Chicago’s Baldwin and King were the dominant pitchers that season; other pitching leaders included Boston’s Bill Daley (.720 winning percentage), New York’s John Ewing (4.88 strikeouts/nine innings), and Pittsburgh’s Harry Staley (.290 opponents’ on base percentage).

Notable batting leaders included Cleveland’s Pete Browning (.373) and Brooklyn’s Dave Orr (.371), the Giants’ Roger Connor (.998 OPS, 14 HR, 6.0 WAR), Harry Stovey from the Boston Reds (97 stolen bases), and the Reds’ Hardy Richardson (146 RBI). Chicago’s Baldwin and King were the dominant pitchers that season; other pitching leaders included Boston’s Bill Daley (.720 winning percentage), New York’s John Ewing (4.88 strikeouts/nine innings), and Pittsburgh’s Harry Staley (.290 opponents’ on base percentage).

John Montgomery Ward enjoyed a solid 1890 season, considering the off-field distraction of his wife leaving him that April.8 In addition to guiding Brooklyn to a second-place finish and anchoring the infield at shortstop, he finished third in hits (188), fourth in runs (134), and fifth in stolen bases (63). Ward had devoted significant time and resources to the PL; Albert Spalding allegedly told Ward that without his efforts, the PL could not have existed.9

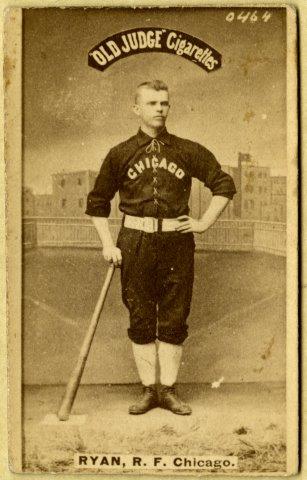

Although the Chicago Pirates finished fourth, they were critical to the league, obtaining seven players from the NL’s Chicago White Stockings (shortstop Charlie Bastian, catcher/infielder Dell Darling, outfielder Duffy, pitcher Frank Dwyer, second baseman Fred Pfeffer, outfielder Jimmy Ryan, and infielder Ned Williamson) and four players from the AA’s St. Louis Browns (catcher Jack Boyle, first baseman/manager Comiskey, starting pitcher King, and third baseman Arlie Latham). Comiskey was instrumental in founding the team, which required him to leave St. Louis; he played for eight years with the Brown Stockings. Comiskey forfeited a potential $8,000 salary with the Browns for the 1890 season to join the upstart league and manage the Pirates in his native city.10

Comiskey was injured in the latter half of the season, and did not compile outstanding statistics (88 games, .244 batting average, 59 RBI, 34 SB). His managerial talents, however, gained notice. He played hurt and was determined to set a good example for his players and. He expected his players to be ready for every game, and his 1890 pitching staff was the best in the league. Comiskey was known for removing players not meeting expectations and for his good eye for spotting talent.

The Players’ League ceased operations following the 1890 season, and two of its clubs (the Boston Reds and Philadelphia Athletics) joined the American Association. The Reds won the 1891 AA Championship, while the Philadelphias finished fifth. Both teams ceased to exist, however, when the AA summarily folded. The Chicago Pirates, along with teams from Brooklyn, New York, and Pittsburgh, merged with the NL teams from their respective cities after the 1890 season.11

The NL owners clamped down even harder on its players following the collapse of the PL in 1890 and the AA after 1891. Interestingly, more than half of the 1890 Pirates did not return to the same league for 1891 as they had played in during 1889, including league leaders Duffy, Baldwin, and King, with catcher Duke Farrell, third baseman Latham, catcher Darling, and pitcher Frank Dwyer. Both Baldwin and King joined the 1891 Pittsburgh Pirates, while Dwyer split the 1891 season between two AA clubs. The other member of the Pirates’ pitching staff, Charlie Bartson, did not reach The Show again; 1890 was his only big-league season.

Three other players, most notably Comiskey, returned to their pre-1890 clubs, while two players returned to the NL for different teams than in 1889. Three players (Ryan, Duffy, and Farrell) played more than 1,200 games with different clubs after the 1890 season. The remaining three (Bastian, Williamson, and Bartson) played fewer than three games in adjacent years. Table 2 depicts player movement from 1889 to 1891, along with games played following the 1890 season.

Table 2: 1890 Chicago Pirates Roster With Adjacent Seasons

| Pos | Player | 1889 ballclub | Age in 1890 | Games Played in 1890 | 1891 ballclub | GP after 1890 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c | Duke Farrell | Chicago White Stockings (NL) | 23 | 117 | Boston Reds (AL) | 1283 |

| 1b | Charles Comiskey | St. Louis Browns (AA) | 30 | 88 | St. Louis Browns (AA) | 407 |

| 2b | Fred Pfeffer | Chicago White Stockings (NL) | 30 | 124 | Chicago Colts (NL) | 632 |

| ss | Charlie Bastian | Chicago White Stockings (NL) | 32 | 80 | Cincinnati Kelly’s Killers (AA), Philadelphia Phillies (NL) | 2 |

| cf | Jimmy Ryan | Chicago White Stockings (NL) | 27 | 118 | Chicago Colts (NL) | 1419 |

| util | Jack Boyle | St. Louis Browns (AA) | 24 | 100 | St. Louis Browns (AA) | 728 |

| if | Ned Williamson | Chicago White Stockings (NL) | 32 | 73 | last game in 1890 | 0 |

| if | Dell Darling | Chicago White Stockings (NL) | 28 | 58 | St. Louis Browns (AA) | 17 |

| ss | Frank Shugart | Elmira (NYS) | 23 | 29 | Pittsburgh Pirates (NL) | 716 |

| p | Mark Baldwin | Columbus Solons (AA) | 26 | 58 | Pittsburgh Pirates (NL) | 155 |

| p | Silver King | St. Louis Browns (AA) | 22 | 58 | Pittsburgh Pirates (NL) | 170 |

| p | Charlie Bartson | Peoria (CI) | 25 | 26 | last ML game in 1890 | 0 |

| p | Frank Dwyer | Chicago White Stockings (NL) | 22 | 16 | Cincinnati Kelly’s Killers (AA), Milwaukee Brewers (AA) | 337 |

One argument raised by ballplayers in favor of the Players’ League was the notion that fans attended games to see the players, not the managers or owners. The attendance figures among the three different leagues from the 1890 season provide evidence for their sentiment. The PL had the highest overall league attendance and average attendance per city among the three major leagues. Interestingly, the lone city in which the PL and NL directly competed and the NL enjoyed a higher attendance figure was Brooklyn, where Ward managed. The NL’s lead may be partially attributable to the Brooklyn Bridegrooms winning the 1890 NL pennant, stars such as Oyster Burns and Hub Collins, and the history already associated with the NL. Chicago’s PL entry notably outdrew the Chicago’s NL Colts, who finished second behind Brooklyn and included Cap Anson on their roster.

The PL significantly outdrew NL in Pittsburgh (by 101,059) & New York (by 87,530). The AA apparently had higher attendance figures than the NL; the AA, however, drew fewer patrons than the other two leagues in the two three-league cities (Brooklyn and Philadelphia). American Association teams were based in smaller cities and were considered by NL owners a lesser threat than those in the PL.

Table 3 depicts the attendance figures for cities with entries in any of the three major leagues that season, with the caveat that “official” attendance figures from the time are not prized for their accuracy.

Table 3. 1890 Attendance Figures12

| City | Players’ League | National League | American Association |

|---|---|---|---|

| Boston | 197,346 | 147,539 | |

| Brooklyn | 79,272 | 121,412 | 37,000 |

| Chicago | 148,876 | 102,536 | |

| Cleveland | 58,430 | 47,478 | |

| New York | 148,197 | 60,667 | |

| Philadelphia | 170,399 | 148,366 | 134,000 |

| Pittsburgh | 117,123 | 16,064 | |

| Buffalo | 61,244 | ||

| Cincinnati | 131,980 | ||

| Baltimore | 34,000 | ||

| Columbus | 85,000 | ||

| Louisville | 206,200 | ||

| Rochester | 82,000 | ||

| St. Louis | 105,000 | ||

| Syracuse | 50,000 | ||

| Toledo | 70,000 | ||

| Total | 980,887 | 776,042 | 803,200 |

The PL’s capitulation after the 1890 season is primarily attributable to financial backers who betrayed the players. On January 16, 1891, the Players’ League officially ceased existence. The PL arguably had a stronger following, but did not have the financial resources to compete with the established NL. Following the 1890 season, the New York and Brooklyn owners negotiated with the National League and ceased operations. Interestingly, the New York Giants played their games at Brotherhood Park, the third structure known as the Polo Grounds and the one the NL’s New York Giants played in until 1957. Unsubstantiated claims of financial mismanagement have been attributed to various individuals through the years, and the PL ceased existence with a negative bank balance. The PL was led by men with baseball knowledge but little financial knowledge; the NL was led by men with some baseball knowledge and greater financial acumen. In the end, the PL leadership could not match the NL’s financial management.13

After the PL folded, Comiskey returned to St. Louis to manage and play first base for the American Association’s St. Louis Browns. The Browns finished second to the AA’s version of the Boston Reds, a team still filled with stars such as Brouthers and Daley from the previous PL season. Hugh Duffy joined the championship Boston Reds in the AA for the 1891 season then played for the NL’s Boston Beaneaters from 1892 through 1900 before finishing his career with the 1906 Philadelphia Phillies. Both Comiskey and Duffy were later elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame.

In a fashion similar to the PL-NL war of 1890, the NL and AA maintained tense relations during 1891. There were disagreements regarding player contracts between leagues, and NL eventually bought out Boston, Columbus, Milwaukee, and Washington following the season; only Washington joined Baltimore, Louisville, and St. Louis for the 1892 NL season. Comiskey’s only option for playing professional baseball during the 1892 season was to play in Cincinnati; his only NL action came with the Reds from 1892–1894.

Following the 1894 season, Comiskey purchased the Western League’s Sioux City Cornhuskers and moved the club to St. Paul, Minnesota, renaming it the St. Paul Apostles. Comiskey owned, managed, and even sparingly played with St. Paul from 1895 through 1899. During these years, Comiskey strengthened his partnership with Western League president Ban Johnson. Comiskey and Johnson met while the latter was the sporting editor of Murat Halsted’s Commercial Gazette and formed a mutual admiration. Eventually the two led the effort to turn the minor Western League into the major American League, directly competing with the National League for supremacy in the national pastime.

Comiskey continued evolving his managerial style while he played and managed during the 1890s. One lesson he learned from his PL tenure was that players and promoters should be separated; from his perspective, players didn’t know enough about financial requirements, while promoters didn’t understand the game itself. Another lesson concerned player readiness, and he learned to gain as much performance from his players as possible.

Although the Chicago Pirates lasted a single season in the short-lived Players’ League, their central role in facilitating player movement among three different leagues, the impact on overall baseball attendance (with emphasis on fans attending games to see star players), and contribution to Comiskey’s approach to running baseball organizations on and off the field in St. Louis, Cincinnati, and Chicago, provide key insights into team and league creation and sustainment.

GORDON GATTIE is a human-systems integration engineer for the U.S. Navy in Virginia. His baseball research interests involve ballparks, baseball records, and statistical analysis. A SABR member since 1998, Gordon earned his Ph.D. from the State University of New York at Buffalo, where he used baseball to investigate judgment/decision-making performance in complex dynamic environments. Originally from Buffalo, Gordon learned early the hardships associated with rooting for the city’s sports teams. Ever the optimist, he now roots for the Cleveland Indians and Washington Nationals. Lisa, his lovely bride who also enjoys baseball, continues to challenge him by rooting for the Yankees.

REFERENCES

Alexson, G.W. (1919). Commy: The Life Story of Charles A. Comiskey. Chicago: The Reilly & Lee Co.

BaseballChronology.com (2014). http://www.baseballchronology.com/baseball/Years/1890/Attendance.asp. Accessed December 15, 2014.

Koszarek, Ed (2006). The Players League: History, Clubs, Ballplayers, and Statistics. Jefferson, NL: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Lewis, Ethan L. (2001). “A Structure to Last Forever: The Players’ League and the Brotherhood War of 1890”. Published on Web; accessed 15 November 2014.

Lowry, Philip J. (2006). Green Cathedrals: The Ultimate Celebration of Major League and Negro League Ballparks. New York: Walker & Company.

Pietrusza, David (2005). Major Leagues: The Formation, Sometimes Absorption and Mostly Inevitable Demise of 18 Professional Baseball Organizations, 1871 to Present. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company.

Sports Reference (2014). http://www.baseball-reference.com/. Accessed December 15, 2014.

Thorn, John; Palmer, Pete; Gershman, Michael; and Pietrusza (2004). Total Baseball: The Official Encyclopedia of Major League Baseball. New York: Viking Press.

Thorn, John (2011). Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game. New York: Simon & Schuster.

NOTES

1 Thorn, 2011.

2 Thorn, Palmer, Gershman, and Pietrusza, 2004.

3 Lowry, 2006.

4 Lewis, 2001.

5 Thorn, Palmer, Gershman, and Pietrusza, 2004.

6 Thorn, Palmer, Gershman, and Pietrusza, 2004.

7 Koszarek, 2006.

8 Koszarek, 2006.

9 Koszarek, 2006.

10 Alexson, 1919.

11 Pietrusza, 2005.

12 BaseballChronology.com, 2014.

13 Koszarek, 2006.