McGraw’s Streak: 26 Consecutive Games Without A Loss in 1916

This article was written by Max Blue

This article was published in Spring 2014 Baseball Research Journal

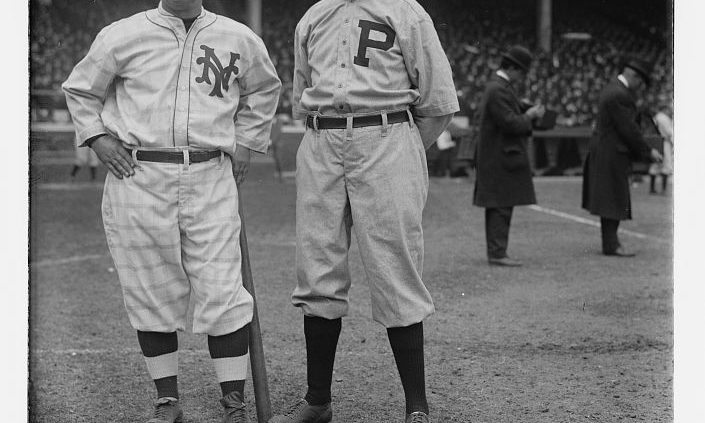

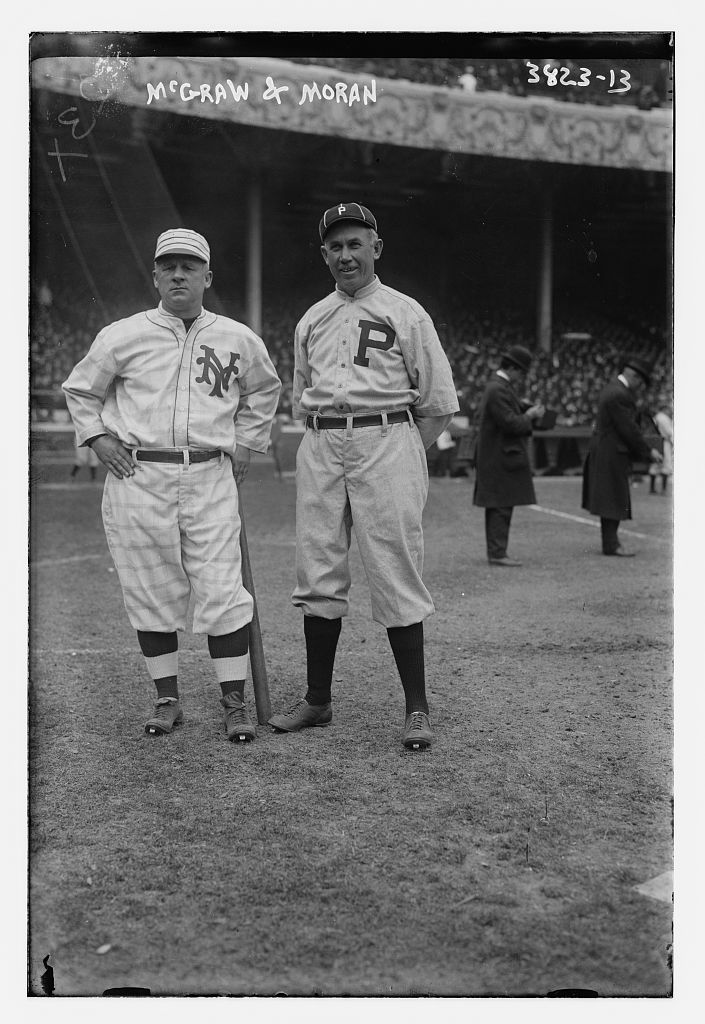

John McGraw, seen with Philadelphia Phillies manager Pat Moran, led the New York Giants to a record-setting 26-game winning streak in 1916. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, BAIN COLLECTION)

On a dreary Friday afternoon, September 29, 1916, 43-year-old John McGraw, manager of the New York Giants, stood in the third base coaching box at the Polo Grounds, swearing at catcher Lew McCarty on first base. McCarty had just smacked a single to left. Had the 150-pound McGraw been coaching first, he would probably have had his hands around the neck of his dim-witted second-string catcher. What McGraw needed was an out, not a hit, because it was the bottom of the fourth, the Giants were leading the Boston Braves 1–0, it was raining, and it was so dark McGraw could not see the Braves’ outfielders. Three more Braves’ outs would give the Giants their 26th consecutive game without a loss. It would have been a 26-game winning streak but for a 1–1 rain-shortened tie with Pittsburgh on September 18, and keep alive their slim chance to win the National League pennant.1

McGraw was no stranger to winning streaks; his Giants won 18 straight in 1904, 17 in 1907, and 16 in 1912. On a road trip in May of this year, his team had run off 17 wins in a row. McGraw knew what it took to keep a streak going.2

With six games to play, the Giants trailed Brooklyn by five games, four on the loss side, but there was still hope. McGraw never stopped hoping because he knew the clock never ran out on a baseball game, though it might on the season. He never stopped reminding his players that when they hit a pop fly in fair territory, two outcomes were possible, the ball could either be caught for an out, or it could fall safely. McGraw believed it was the sacred duty of the man who hit the ball to assume the ball would fall safely and run as fast as he could, on the chance that he might reach base or take an extra base. That was the way John McGraw played the game and he demanded no less of his players. In a 16-year playing career, McGraw reached base 46.6 times for every 100 plate appearances, a figure exceeded in major league history only by Ted Williams (48.3) and Babe Ruth (47.4).3

McGraw also demanded that his team play smart and take advantage of every game situation. Lew McCarty should have known that the game situation required him to strike out as quickly as possible so the Giants could hurry to make this an official game, the 26th consecutive game without a loss.

For more than three weeks McGraw—who was sometimes called “Little Napoleon” and “Mugsy,” but more often Mister McGraw—had been driving his Giants day after day to win. He had almost convinced them that they would never lose again. Six more wins and they would have run the table, going undefeated for the final 32 games of the season. When they showed up for work at the Polo Grounds on September 7 their record was a dismal 59–62; now 22 days later, if the rain would hold off for just three more Braves’ outs, the Giants would stand at 85–62. But it was not to be. McGraw was a powerful force on the ballfield, but even he could not control the weather.

Shortly after four o’clock, umpire William J. “Lord” Byron called the game off, much to the disgust of McGraw who was ready to continue play in the downpour. McGraw chided himself for not scheduling a two P.M. start instead of the normal 3:00 p.m. With games averaging a little over an hour and a half, there was rarely a problem, but this was hurricane season on the East Coast, and he should have taken it into account. If the game was not completed, the only way it could be made up would be to play three games the following day, which McGraw took seriously enough to discuss the possibility with Braves manager George Stallings. Playing a game on Sunday would be allowed only if it were an exhibition game played for charity.

McGraw had a long list of things he did not trust, including hotel clerks, telephones, and left-handers, but his hate list was short—umpires, bad hops, Republicans, and rain—the things he could not control. McGraw had been manager of the Giants since 1902, and in those 14 years had won 1,235 games.4

McGraw’s first full year as manager was 1903, and in the years since then he had averaged 93 wins per season, winning five pennants, which would have been six but for the perfidy of umpire Hank O’Day who had called Fred Merkle out for failing to touch second base, costing them the 1908 pennant. McGraw would go on to manage the Giants for another 17 years, and become the all-time winningest manager in National League history with 2,699 wins, and a winning average of .586. But the 1,948 losses eventually took their toll and McGraw died young, a year after retiring from the game in 1933.

But this story is about the streak, and McGraw’s team, a motley collection of unlikely heroes, none of whom would ever appear on the 100 best players of the century list. For three magical weeks in the fall of 1916 they were unbeatable, achieving the longest unbeaten streak in baseball history.5

In this time they actually played 29 and a half games, counting the four-inning rainout. They also beat the Yankees and the minor league New Haven team in exhibition games and played a 1–1 tie with Pittsburgh, called after eight innings because of rain. All the major league games, including nine double-headers, were played at the Polo Grounds. The average time of game was 1 hour, 44 minutes. For the entire time, including the exhibition game, and all the double-headers, McGraw used exactly the same lineup and batting order, except for the two catchers.

And the pitchers! Ah, the pitchers. Does anybody remember these names? Pol Perritt 6–0, Jeff “the Ozark Mountain Bear” Tesreau 7–0, Ferdie Schupp 6–0 with four shutouts, Rube Benton 5–0, and Slim Sallee (off the sick list) 2–0. Using a bewildering array of “moist” balls, curves, and fastballs, with pinpoint control (33 walks in 240 innings) the staff turned in 23 complete games, including 10 shutouts, and seven one-run games. They were aided by superb fielding that played 14 errorless games (compared to the opponents’ three), and executed 15 double plays. The Giants racked up 122 runs, 223 hits, 22 errors. Brooklyn, Philadelphia, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Chicago, St. Louis, Boston: 33 runs, 151 hits, 50 errors.

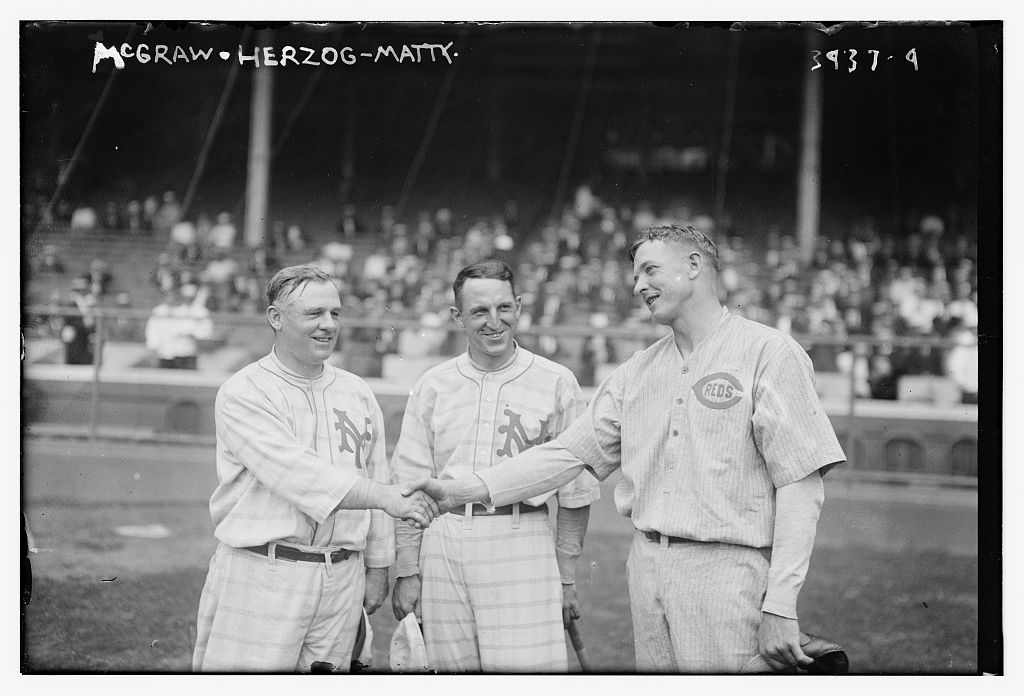

New York Giants manager John McGraw, left, shakes hands with his longtime star pitcher and close friend Christy Mathewson, right, as infielder Buck Herzog looks on. Due to Mathewson’s desire to manage in the big leagues, McGraw traded him to the Cincinnati Reds on July 20, 1916. Mathewson managed the Reds for parts of three seasons. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, BAIN COLLECTION

Game One. Thursday, September 7. It looked like another Giants loss. Zack Wheat, batting cleanup and following right fielder Casey Stengel in the Brooklyn lineup, whaled a home run into the right-field grandstand to lead off the second inning, and Brooklyn left-hander Nap Rucker threw blanks at the Giants through five innings. In the sixth the game got ugly; the Dodgers began to dodge. With two out and two on due to free passes, Giants shortstop Art Fletcher grounded weakly to short where Ivy Olson booted it to load the bases for Benny “the Ty Cobb of the Federal league” Kauff. Benny managed a swinging bunt to third for an infield hit that tied the score. Next came the big first-sacker, switch-hitter Walter Holke, the only rookie in the Giants lineup, who rapped a single to left for two runs and a 3–1 Giant lead. Holke’s hit opened some eyes because he was playing in only his seventh major league game. In Holke McGraw had found the final piece. Catcher Bill Rariden completed the Dodgers’ misery with yet another infield hit, and the Giants won 4–1 when left-hander Ferdie Schupp pitched no-hit, no-run ball after the second inning. Fred “Bonehead” Merkle, now with the Dodgers and the man Holke had replaced, made the next-to-last out.

Table 1: NL Standings at start of play Friday, September 8, 1916

|

|

W |

L |

GB |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Philadelphia |

75 |

49 |

— |

|

Brooklyn |

74 |

51 |

1½ |

|

Boston |

71 |

51 |

3 |

|

New York |

60 |

62 |

14 |

|

Pittsburgh |

61 |

67 |

16 |

|

Chicago |

59 |

72 |

19½ |

|

St. Louis |

56 |

75 |

22½ |

|

Cincinnati |

51 |

80 |

25½ |

Game Two. Friday, September 8. The Giants treated the best pitcher in the National League, Philadelphia’s Grover Cleveland Alexander, like chopped liver, raking him for 13 hits and eight runs (five earned) in seven innings. They would notch a 9–3 win behind Jeff Tesreau who, in addition to his darting “moist” ball, contributed a home run to the festivities. Game two of the scheduled twin bill was postponed because of rain.

Games Three and Four. Saturday, September 9. Thirty-five-thousand New Yorkers roared their approval as lanky right-hander Pol Perritt went the distance twice. First he defeated the defending-champion, league-leading Phillies 3–1, then changed his shirt, and blanked them 3–0 in game two, besting Chippewa Chief Bender. Art Fletcher sealed the game one win with an eighth inning steal of home.

Sunday, September 10. Baseball was not usually played in New York on Sunday because of certain laws, but the laws were relaxed if the game was played for sweet charity, so the Giants squared off against the American League Yankees in front of 20,000 fans and a few movie cameras. John McGraw was not easing up, even for an exhibition game, and went with his regular lineup, including starting pitcher Ferdie Schupp on two days’ rest. Ferdie went three and two thirds before turning it over to veteran right-hander Fred Anderson who breezed to a 4–2 Giant win, helped by a home run from “Little Benny” Kauff. It was hard to believe Kauff could generate so much power from his 5’8″, 157-pound body, especially the way he choked up on the bat.

In 1916 everybody choked up, the amount varying with position in the batting order. Leadoff hitters choked up three inches, numbers three, four, five, and six hitters, at least an inch. One reason why games moved so briskly is there were few strikeouts and few home runs. Pitchers worked fast and aimed for the middle of the plate. That meant few deep counts and many complete games.

Game Five. Monday, September 11. The Giants were back to their job of pounding the Phillies. On the tide of a six-run fourth inning, featuring a three-run triple by catcher Bill Rariden off Eppa Rixey, and another homer by “Little Benny,” the Giants coasted to a 9–4 win behind Ozark Jeff Tesreau. McGraw’s twirlers pitched long, and they pitched often.

Game Six. Tuesday, September 12. The 5,000 or so Giants rooters who came out to see the team win their sixth straight game, 3–2 against the last place Cincinnati Reds, were treated to an odd sight. Standing across the field in the disguise of a Cincinnati uniform was a man who over the last 15 years had pitched 372 victories for the Giants, not including the three shutouts in five days against the Philadelphia Athletics in the 1905 World’s Series. Yes, it was Reds manager Christy Mathewson who had been swapped, along with third baseman Bill McKechnie and Edd Roush, to the Rhinelanders in June for Red Killifer and their manager, Buck Herzog, who was now batting second and anchoring second base for the Giants. Herzog, whom McGraw made field captain, accounted for the Giants’ first run with an RBI double in the first inning after the Redlegs got off to a 2–0 lead. Davey Robertson, Giants’ right fielder, and number three hitter, tied the game with an upper deck homer to right in the fourth, and the winning run scored in the fifth while pitcher Rube Benton hit into a double play. After the first inning, left-hander Benton handed the Reds a string of eight goose eggs.

Games Seven and Eight. Wednesday, September 13. In game one, young Holke settled the issue with a bases-loaded sixth-inning triple off Reds’ ace Fred Toney, and Ferdie Schupp, back again with two days rest, made it stand up with a three-hit shutout. Not counting the exhibition game, the skinny lefty had now thrown 16 consecutive scoreless innings. The Giants did not waste time in game two, scoring five runs in the first inning which turned out to be enough when Giants rookie right-hander “Columbia George” Smith pitched into the sixth, and then handed off to Pol Perritt who silenced the Reds thereafter. Giants 6, Cincinnati 4.

Game Nine. Thursday, September 14. The Giants found a new way to win: base on balls, stolen base, single to center. It worked in the first when Robertson scored on a hit by Zimmerman, and again in the fourth when Kauff was plated on a hit by Holke. McGraw had pried third baseman Heinie Zimmerman, the veteran RBI man, away from the Cubs in a late season trade for “Laughing Larry” Doyle, and installed him in the cleanup spot. It may not be a coincidence that the streak began a week after Zimmerman joined the team. The Reds squeezed out a run in the eighth, but it was not enough. The Ozark bear hunter, back again on two days rest, was using his “moist” ball, which dived as it approached the plate, to perfection; only four fly balls were hit to the outfield.

Friday’s game was rained out.

Games 10 and 11. Saturday, September 16. Game one was easy as Rube Benton held Pittsburgh to two runs, and the Giants put the game away with a five-run lucky seventh, winning 8–2. Game two was another story. The Giants were blanked into the eighth by slim Pirate left-hander Wilbur Cooper, and trailed 3–0 as McGraw used four pitchers trying to keep the game close; two Giant double plays helped. The Giants took advantage of a Pittsburgh error to score two in the eighth on a ground out from Buck Herzog and a two-out single to center by Davey Robertson. They won it in the ninth on a walk-away two-out smash up the middle by leadoff man George Burns after the tying run scored on a passed ball. Tesreau pitched the ninth for the win. Twenty-two thousand fans were delirious.

Game 12. Monday, September 18. After a Sunday day of rest, the Giants and Pirates were back for another double-header. The Giants managed to score only three runs all day, but prevailed when Ferdie Schupp and Pol Perritt held the Pirates, and the fearsome Honus Wagner, who McGraw always said was the best ball player he ever saw, to only one run. Schupp won the opener 2–0 on hits by McCarty and Zimmerman. The nightcap was called after nine innings because of rain with the teams tied 1–1. The Giants’ run came on a fifth-inning inside-the-park home run by Benny Kauff. Honus Wagner tied it with a eighth-inning sacrifice fly. McGraw was inconsolable.

Games 13 and 14. Tuesday, September 19. For the third time in four days the Giants and Pirates squared off in a twin bill. The Giants put aside the number 13 jinx quickly, winning game one easily, 9–2 behind Fred Anderson and Rube Benton. With batting help from Georgie Burns and Benny Kauff they took the nightcap 5–1 behind Jeff Tesreau. Kauff homered in both games. The New York Times beat writer said Benny’s second game four-station clout was slammed so hard that it arrived limp and breathless into the upper deck boxes. New York fans showed respect for a fading warrior when they applauded every appearance of eighttime National League batting champion Wagner, now nearing the end of his celebrated career. In the six games, the 42-year-old “Flying Dutchman” went 1 for 17 but drove in the game tying run in the only game the Pirates didn’t lose.

Game 15. Wednesday, September 20. The Giants added the Chicago Cubs to their victim list, scoring the winning run on a seventh-inning three-bagger by Lew McCarty. Ferdie Schupp, pitching on one day’s rest, saw his 27 consecutive scoreless inning streak stopped, but went the distance again to win 4–2, the Cubs’ second run scoring on two Giants’ errors.

Game 16. Thursday, September 21. Pol Perritt, with two days’ rest, blanked the Cubs 4–0, the Giants scoring single runs in the first, second, fourth, and sixth. The second-inning run came when catcher Bill Rariden hammered a pitch into the flower bed in deep right center. It was Bedford Bill’s only home run of the year, and one of only seven hit in a 12-year major league career.

Game 17. Friday, September 22. Southpaw Slim Sallee came off the sick list to give the gritty Giant pitching staff a lift with a seven-hit shutout of the Cubs, and the Giants won 5–0, equaling an early-season 17-game winning streak which was achieved entirely on the road, and was thus less appreciated by local fans. Today’s game was highlighted by two double plays, and numerous circus plays by Zimmerman, Fletcher, and Herzog who “scoured the infield of hits until it was as clean as a newly polished kitchen.” Batting muscle was furnished by Robertson, Rariden, and Kauff.

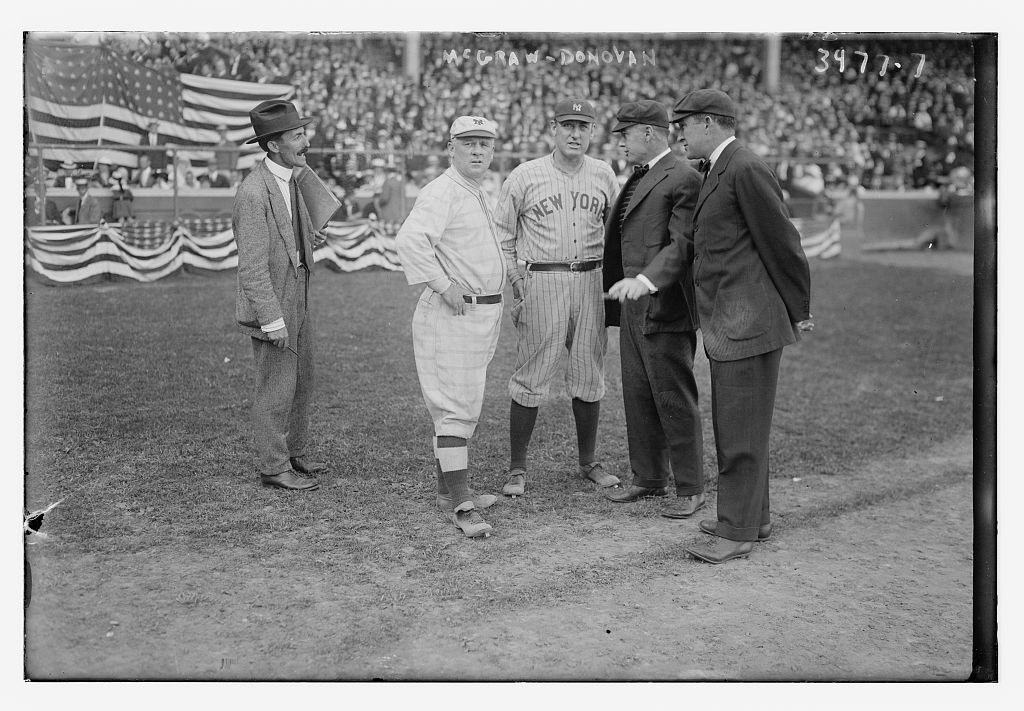

John McGraw is pictured here in 1916 with Wild Bill Donovan, the manager of the New York American League club, and two umpires. (LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, BAIN COLLECTION)

Games 18 and 19. Saturday, September 23. The Giants turned their attention to the St. Louis Cardinals, and thumped the Birds twice, 6–1 and 3–0 in seven innings when play was stopped by rain. Jeff Tesreau and Rube Benton handled the pitching. Umpire “Lord” Byron got into the act by sending Giants’ pitcher Bill Ritter into oblivion, and later Cardinal manager Miller Huggins, who put on a splendid display of verbal gab before leaving the field. Zimmerman drove in runs in both games.

Games 20 and 21. Monday, September 25. The Giants beat the Cardinals two more times before 10,000 cheering spectators. In the opener, Ferdie Schupp fired a two-hitter, and the Giants hung on for a 1–0 nail-biter, the winning run scoring in the fourth inning on a wild throw as the Giants were held to only three hits by St. Louis sophomore right-hander Lee Meadows. The nightcap was easy as the Giants jumped on Joe Lotz for five early runs, and breezed to a 6–2 win behind Pol Perritt.

Game 22. Tuesday, September 26. The Giants, playing loose and easy, broke the record for longest unbeaten streak, held by Cap Anson’s 1880 Chicago, with another comfortable win over the hapless Cardinals. Slim Sallee took only an hour and 35 minutes to dispatch the Birds 6–1, and contributed two hits and an RBI to the fun.

Game 23. Wednesday, September 27. The Giants pulled one out. Unheralded Cardinal rookie left-hander Bob Steele came within one pitch of ending the streak, but with two on, two out, and two strikes on the hitter, made a mistake to Buck Herzog who tripled off the right field wall to tie the game at two. Steele heaved a ball over catcher Frank Snyder’s head, allowing Heinie Zimmerman to score the winning run in the bottom of the tenth. McGraw used a committee of pitchers. Fred Anderson’s moist ball was all over the place, and the Giants were lucky to trail by only two when McGraw yanked him after two and one third innings … he had yielded six hits and two walks. Rube Benton held the fort for four and two thirds, then handed off to George Smith for two. Bill Ritter pitched the tenth, and got the win.

Baseball is like a flowing river, veterans drifting downstream to an ocean of retirement, rookies boldly swimming against the current, seeking the limits of their abilities. For those in attendance it was easy to acknowledge the achievements of the old-timers as they drifted on down, but to spot the potential future star, struggling to make his mark, was a different story. New Yorkers following the improbable Giants’ streak, were quick to cheer the aging Honus Wagner as he passed through.

They most likely missed the 20-year-old Cardinal rookie third baseman, Rogers Hornsby, who managed only three singles in 21 at bats in the six Cardinal defeats. Hornsby would go on to become one of the greatest offensive forces the game has ever seen, winning seven National League batting titles.

Games 24 and 25. Thursday, September 28. After 18 straight games against teams below them in the standings, the Giants had to play the final nine games of the season against teams above them. Five against Boston, and four against Brooklyn. They began the stretch in fine fashion, Jeff Tesreau and Ferdie Schupp throwing 18 ciphers at the Beantowners as the Giants won 2–0 and 6–0. The opener was settled on a home run by Davey Robertson, and the nightcap saw two baseball rarities, a near no-hitter by Ferdie Schupp, scored on in only two of his last 52 innings pitched, and a grand slam inside-the-park home run by Benny Kauff.

At the end of the day, New York sports writers took a deep breath, and allowed that there was yet a way, though convoluted, that the Giants could win the pennant. They would never consider this if they had not become convinced, like everyone else, that the Giants would never lose again. It was like this:

Table 2: NL Standings, Friday, September 28, 1916

|

|

W–L |

To play |

Opponents |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Brooklyn |

90–58 |

6 |

2 vs. PHI, 4 vs. NYG |

|

Philadelphia |

88–57 |

8 |

2 at BRO, 6 vs. BSN |

|

Boston |

84–60 |

9 |

3 at NYG, 6 at PHI |

|

New York |

84–62 |

7 |

3 vs. BSN, 4 at BRO |

If the Giants ran the table, Boston would be eliminated for they would have 63 losses. Philadelphia had to lose six of eight, and Brooklyn one of two to Philadelphia assuming they lose all four to the Giants. It was possible. McGraw told his club to forget about what is past; they are beginning a seven-game season, and they must win them all.

On Friday the weeping heavens saved the Braves, and left the Giants doing some weeping of their own. The Giants led 1–0 behind Pol Perritt, with one out in the bottom of the fourth, but it was so dark at ten minutes till four, and the rain was coming down so hard, that Lord Byron called a halt over the intemperate beefs of the desperate McGraw. The game could not be made up. Across the East River in Brooklyn the game between the Robins and the fighting Phillies had also been washed out, and would be played as part of a twin bill the next day, the first game beginning at 10:30 in the morning.

Game 26. Saturday, September 30. Everybody was scoreboard watching, all 28,000 fans and the peanut vendors. The game began with the knowledge that the Phillies had trounced the Robins 7–2 in the morning game to take over the league lead. The Giants’ Rube Benton took a cue from Ferdie Schupp, and threw a second straight one-hitter at the Braves’ slumbering bats, extending their consecutive scoreless inning streak to 27. They had yet to score in the series. Riding triples by Burns and Fletcher, the Giants scored two in the seventh, and two in the eighth to win 4–0. The Giants were down to a five-game season.

Strike three. Saturday, September 30. Game two. The Braves seemed helpless against left-handers, and Slim Sallee had three days rest, as he swaggered to the mound for McGraw. For three innings Sallee stifled the Braves, but the scoreless streak ended in the fourth when the unthinkable happened: steady shortstop Art Fletcher made a wild throw letting a runner on and eventually leading to two runs scoring. The Giants fought back to tie in the fifth, after Lew McCarty walked, igniting a two-run rally. In the seventh, “Big Ed” Konetchy, the Braves’ first baseman, the man who had broken up both Ferdie Schupp’s and Rube Benton’s no-hitters, singled to center. Braves’ third baseman Red Smith took two strikes, then began to foul off pitches as Sallee tried to put him away. Tension mounted as Smith gained confidence with each swing, and Sallee seemed to sag. The sixth foul ball of the at bat was a long fly into the left field grandstand, and suddenly the crowd sensed doom. Even Sallee seemed to know, as he stalked around the mound muttering to himself.

Captain Herzog came in to talk with him, try to settle him down. Finally he threw the pitch, and immediately knew it was a mistake. Smith measured the approaching ball, shifted his weight in a practiced motion, and swung with all the strength he owned. It was a home run off the bat, and the Giants trailed 4–2. The Giants had surrendered only two home runs in the preceding three weeks, one to Gavvy Cravath of the Phillies and one to Jack Smith of the Cardinals.

It was the first time in 17 days that the Giants had given up as many as four runs in a game. But the worst was yet to come. Sallee’s next pitch to Sherry Magee was also belted into the left field grandstand. Back-to-back homers! McGraw called on Tesreau to stop the bleeding, but the brutal pace finally proved too much. The Ozark bear hunter was out of steam. He faced four batters and they all smacked hits. Braves shortstop Rabbit Maranville was all over the place to snuff every Giants’ rally.

Final score: Boston 8, Giants 3. The streak was over.

Across the river at Ebbets Field in Brooklyn, Robins’ right fielder Casey Stengel sparked his team to a big win over the Phillies with a fifth inning home run off Phillies’ ace Pete Alexander. In 1916 Alexander, a 33-game winner with 16 shutouts, was virtually unhittable, except when he pitched in New York. Recall on September 8, in the second game of the streak, the Giants shelled the great Alexander for 13 hits, and today in Brooklyn, in a game that could have put the Phillies in the catbird seat, “Old Pete” failed again. There were those who claimed New York teams held an edge because visitors were dazzled by New York nightlife. Some also claimed the Giants’ shiny streak owed more than a little to the Great White Way. Perhaps. But who was to say the hometown Giants were tucked in by nine?

In any case, at the end of the day the Giants were cooked. Five games back with four games to play. Where did they go from here? They went to Brooklyn.

Wilbert Robinson, manager of the Robins, was an old teammate of McGraw’s when they played for the Baltimore Orioles back in the gay nineties. The Giants were out of the pennant race. McGraw was in a position to help “Uncle Robby” whose team entered play with a one-half game lead on the Phillies who were playing a double-header against Boston in Philadelphia. To suggest this to McGraw would be to invite a punch in the nose. McGraw played to win. Period.

McGraw sent out his ace Ferdie Schupp who had given up only five hits in his current 23-scoreless-inning stretch. Pitching for the Robins was “Long Jack” Coombs who in 1910, while twirling for the Philadelphia A’s, pitched three complete game World’s Series victories against the Chicago Cubs.

The Giants loaded the bases with two outs in the first inning, and Benny Kauff, who batted in 23 runs during the streak, went to war against Coombs, fouling off pitch after pitch, exceeding a half dozen before Coombs finally put him away with a diving spitter that got Benny lunging. After that Coombs toyed with them, throwing a mixture of stuff “not hard enough to break tissue paper.” The Giants fell 2–0. The Giants had a two-game losing streak. The Robins edged closer to the pennant when the Phillies split with Boston.

On Tuesday the unimaginable happened. McGraw lost control of his team. The Giants played loose and carelessly. They ignored their manager’s signals, Pol Perritt more than once went into a windup with a man on first or second, Captain Buck Herzog made repeated trips to the mound to scold first Rube Benton, then Pol Perritt for indifferent pitching. The Robins scored nine runs. McGraw couldn’t stand to watch; he left the dugout in the fourth inning. He announced that he was disgusted with the Giants’ play, and would not be associated with such shenanigans. The Robins would have won the pennant in any case because the Phillies folded before Boston, losing both games, but the Giants’ players did not know this while the game in Brooklyn was in progress.

The Giants gathered themselves to win the next day when the pennant race was over and they lost the final game of the season on Thursday, but McGraw was long gone. When he left the field on Tuesday he headed straight for the racetrack in Laurel, Maryland, looking for a hot tip or playing a hunch. He was through with baseball.

***

P.S. When the Black Sox Scandal broke after the 1919 World’s Series, the Chicago players were not the only ones booted out of baseball. Rube Benton, Buck Herzog, Heinie Zimmerman, and Benny Kauff were all fingered as in on fixes from time to time. Zimmerman and Kauff were banned for life, Kauff officially for being part of an alleged auto theft ring.6

John McGraw got over his pique. He came back to manage exactly the same team that was unbeaten for 27 straight games for him in September 1916 to the 1917 National League championship, winning 98 games for a 10-game edge over the Phillies. Brooklyn won only 70 games, and dodged to seventh place. The Giants lost the World’s Series four games to two to the same Chicago White Sox team that disgraced baseball two years later.

MAX BLUE is the pen name of Paul Fritz who has been ensnared by the game of baseball for more than 75 years, and a SABR member for many years. In 1950 Fritz was a catcher for the Appleton Papermakers, a Class D farm club of the St. Louis Browns in the Wisconsin State League. Blue is the author of “God Is Alive” and “Playing Third Base for the Appleton Papermakers,” as well as three published books about the Philadelphia Phillies.

Notes

1 The New York Times microfilm archives, September–October 1916, were the source for all the game information presented in this work.

2 Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. List of Major League Baseball’s longest winning streaks.

3 John Thorn, Pete Palmer, Michael Gershman, and David Pietrusza, “All-Time Leaders: On Base Percentage,” Total Baseball, 5th edition, (New York: Viking Penguin, 1997) 2275.

4 “The Manager Roster,” Total Baseball, 2330.

5 Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. List of Major League Baseball’s longest winning streaks.

6 Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia. List of People banned from Major League Baseball.