Mike Gonzalez: The First Hispanic Cub

This article was written by Lou Hernandez

This article was published in The National Pastime: Baseball in Chicago (2015)

On September 28, 1912, 22-year-old Mike González became the first Hispanic player to don the tools of ignorance in the major leagues with his debut with the Boston Braves.

Five years later, as a member of the St. Louis Cardinals, González confounded Philadelphia Phillies backstop Bill Killefer and his pitcher Joe Oeschger by stealing home in the bottom of the 15th inning to defeat Oeschger and the Phillies 5–4 at Robison Field.

Cardinals manager Miller Huggins was reported to have conferred with González afterward and said, “You stole without my signal. You’ve got plenty of guts.”

González replied: “I also got plenty big lead.”1

Two seasons later, in 1919, the New York Giants claimed González off waivers from St. Louis. He played sparingly for New York for three seasons. Then, following the 1921 campaign, González was absent from the Big Time for two years, plying his trade in the minors. The Cardinals re-obtained the nine-year major leaguer prior to the 1924 season from the Brooklyn Robins, who had purchased González from the American Association’s St. Paul Saints.

The dependable receiver was the Cardinals’ number one catcher on the season. While statistics are not complete for 1924, he is at this point “leading” the National League in games started behind the plate (114) and innings (914 2/3 ). He may not end atop the league, but his final totals will be higher.

In May 1925, the Chicago Cubs cleared the way for Gabby Hartnett to become the team’s regular catcher by shipping their everyday backstop Bob O’Farrell to the St. Louis Cardinals. In return, Chicago received promising infielder Howard Freigau and González. Freigau spent barely two seasons with the Cubs, while González played the last five productive campaigns of his major league career with Chicago.

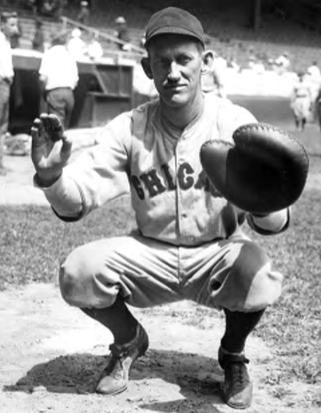

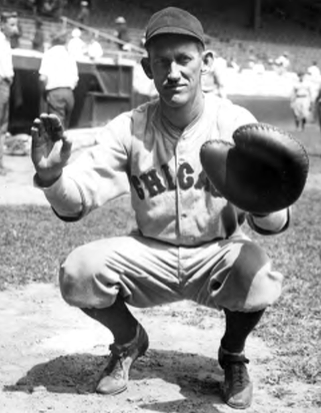

At the time of his trade to the Cubs, González was among nearly 400 active major league players born in the 19th Century. Miguel Angel “Mike” González was born in Havana, Cuba on September 24, 1890. He was among the few Hispanic players on a major league roster in the big leagues in 1925.

Table 1: First Latin American player to homer in historic NL ballparks

| Ballpark | City | Player | Date |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baker Bowl | Philadelphia | Mike González | 7/30/1924 |

| Braves Field | Boston | Mike González | 8/28/1925 |

| Ebbets Field | Brooklyn | Mike González | 6/4/1918 |

| Wrigley Field | Chicago | Mike González | 6/9/1925 |

| Forbes Field | Pittsburgh | Luis Olmo | 7/26/1943 |

| Polo Grounds | New York | Armando Marsans | 8/1/1912 |

| Redland/Crosley Field | Cincinnati | Adolfo Luque | 8/15/1924 |

| Robison Field | St. Louis | Mike González | 4/25/1917 |

| Sportsman’s Park | St. Louis | Mike González | 7/22/1924 |

González had begun the 1925 season with St. Louis as a starter until his trade to the Cubs on May 23. Following the trade, González became Hartnett’s back-up for three and one-half seasons. On May 25, the 34-year-old catcher became the first Hispanic player in Chicago Cubs history when he pinch-hit for reliever Elmer Jacobs in the seventh inning of a Cubs/Pirates game at Forbes Field. In a curious move, Cubs manager Bill Killefer asked González to sacrifice, instead of letting his pitcher do so. González did so successfully, and he did not stay in the game. The Cubs were defeated, 5–3.

In his third start for the Cubs, on June 9, the 6-foot-1, 200-pound González enjoyed a 3-for-5 day at the plate.

In his last at-bat, in the bottom of the ninth, he homered off the Giants’ Jack Scott with no one on base. That cut New York’s lead to 9–7, which is how the game ended. “A high wind helped Meusel, Terry and Southworth of New York and Gonzales (sic) of Chicago crack home runs,” 2 read a wire report, indicating the direction in which the wind was blowing on Chicago’s North Side that day. (González’s name was often misspelled in the press.) The breeze-aided home run by Mike was the first home run hit by a Hispanic player at 11-year-old Cubs Park.

Though such ethnic distinctions were not recognized by reporters of the era, a fine Tuesday afternoon crowd of 15,000 was present for the high-scoring encounter between the first-place Giants (31–15) and the sixth-stationed Cubs (20–28).

Two years prior to being renamed in honor of Cubs owner William Wrigley Jr., and a year before undergoing expansion that would increase its capacity to 38,396, Cubs Park at the time was a single-grandstand compound with a maximum capacity of 20,000. The left field line stretched 319 feet to the foul pole, while the chalk line measured 318 feet to right. Straightaway center field was a deep 447 feet away. 3

The Cubs finished last in 1925, but improved steadily over the next four seasons under new manager Joe McCarthy. In his fourth season at the helm, McCarthy led the Cubs to the pennant by 10½ games. The former Cubs Park hosted the first of its five World Series in the 20th Century, beginning on October 8, 1929.

What was called a “limp arm” left Gabby Hartnett unable to throw for much of the 1929 season. González and Zack Taylor shared the catching duties for the National League champions. In the World Series, Taylor, who had enjoyed a better season with the bat, started all five games against the AL champion Philadelphia Athletics.

In Game One at a now double-decked Wrigley Field, González entered the contest after Taylor had been pinch-hit for in the home seventh. The Cubs’ Guy Bush relieved starter Charlie Root in the same inning. The game was 1–0 for the Athletics until Philadelphia scored two unearned runs in the ninth. González recorded two putouts in plays at the plate in the same half inning. In the bottom of the inning, the Cubs scratched across a run, avoiding the shutout.

When González’s turn to bat in the ninth came up, with the tying runs on first and second, McCarthy substituted Footsie Blair with the stick. The pinch-hitter grounded out, and the next batter, another emergency swinger, Chick Tolson, struck out, ending the game. With his two innings of defensive work, Mike González became the first Latin American position player to appear in a World Series game.

The next day, in Game Two, González pinch-hit for Cubs relief pitcher Hal Carlson in the bottom of the eighth. Philadelphia led 9–3, which was eventually the final score. González struck out swinging on three pitches, foul tipping the second offering. The 39-year-old receiver saw no further action in the remaining three Fall Classic games, as the Athletics took two of the next three contests in Philadelphia to claim the title.

On January 2, 1930, the Cubs released González. The veteran catcher latched on with Minneapolis of the American Association for the 1930 campaign. His familiar St. Louis Cardinals brought González back to the major leagues in early June of 1931. The weak-hitting backstop played sparingly for the Cardinals, who won the National League pennant and then the World Series over Connie Mack’s repeat American League champions. González was not included on the Cardinals’ World Series roster.

In 1932, González played the last 17 games of his 17-year major-league career. His role was as the team’s third-string catcher. Two seasons later, in 1934, González became the first Hispanic coach in the major leagues under Cardinals manager Frankie Frisch. “Mike Gonzalez was considered such an asset to the Cardinals that he served as a coach under four different pilots,” wrote J.G. Taylor Spink a dozen years later.4

González also twice served as interim manager of the Redbirds. The first time came on September 14, 1938, his first game as replacement skipper for the fired Frisch. Mike also earned the honor of becoming the first Hispanic manager in major league history.

Always looking for big league talent, González was credited as the source of an all-time classic baseball line, in describing a potential player’s ability. A newspaper report from the 1930s described the reason for his famous quip. “His club’s scouts had been sending in long telegrams about worthless prospects. Sick and tired of footing heavy telegraph tolls and getting nothing in return, the club sent Mike scouting with instructions to report as briefly as possible. Mike looked a recruit over and wired, ‘Good field. No hit.’ ” 5

Following his retirement as a big league player, the superannuated catcher played a couple of more winter league seasons with the Habana Leones before hanging up his spikes for good in 1935 at age 45. (We are staying faithful to the actual spelling, in Spanish, of the team “Habana,” while maintaining the more well-known English-spelling of the capital city. ) He played 23 seasons with Habana. González maintained his long association with the popular team as its manager, and in the early 1940s, he was part of a group of business associates that purchased the club from the former owner’s widow. Before the decade had ended, the shrewd former player had become the team’s principal owner.

In early October of 1953, the 63-year-old González stepped away from the Leones’ dugout after 33 seasons as manager. He was the winningest manager in Cuban Winter League history (851–674). 6 He continued as the league’s most recognizable and influential owner for the remainder of the decade. Among the select group of skippers González chose to succeed him at the helm were fellow Cubans Salvador “Chico” Hernández and Dolf Luque.

Luque and González were the best known Hispanic major league ballplayers of the first half of the 20th century. González had broken into the big leagues in 1912, with the Boston Braves, two years ahead of Luque, who was a standout pitcher with the Cincinnati Reds in the 1920s. Luque was the first Latin American player to participate in a World Series, taking the hill for the 1919 Reds.

The thriving Cuban Winter League was abolished in 1961 following Fidel Castro’s Marxist revolution of two years earlier. González’ signature Habana Leones franchise was taken from him by Castro’s dictatorial regime and dissolved. Like all owners of the Cuban Winter League teams, he received not a dime of compensation. The franchise was estimated to be worth some $500,000 at the time. 7

Miguel Angel González lived another 16 years, one imagines with an embittered heart. He died, on February 19, 1977, of a heart attack in Havana. He was 77.

LOU HERNANDEZ is the author of three baseball histories. He resides in South Florida and roots for the Marlins.

Sources

Baseball-Reference.com

Retrosheet.org

Figueredo, Jorge, S. Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball 1878–1961. McFarland & Co., Jefferson, N.C., 2003.

González Echevarría, Roberto. The Pride of Havana. A History of Cuban Baseball. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y. 1999.

Notes

1 “Beisboleros.” Newsweek May 29, 1944. The game took place on June 11, 1917.

2 “Giants Capture 19 of 28 Games Without McGraw.” Alton Evening Telegraph, June 10, 1925.

3 Curt Smith. Storied Stadiums. Foreword by Bob Costas. Carroll & Graf Publishers, New York, New York 2001.

4 J. G. Taylor Spink. “Looping the Loops.” The Sporting News, October 30, 1946.

5 “Adolfo Luque Hangs On.” The Kansas City Star, January 27, 1933.

6 Jorge S. Figueredo, Who’s Who in Cuban Baseball 1878–1961. McFarland & Co., Jefferson, N.C., 2003.

7 Roberto González Echevarría. The Pride of Havana. A History of Cuban Baseball. Oxford University Press, New York, N.Y. 1999.