“Never Make the Same Mistake Once: Remembering USC Baseball Coach Rod Dedeaux

This article was written by Bob Leach

This article was published in The National Pastime: Endless Seasons: Baseball in Southern California (2011)

Actor Jack Lemmon toes the rubber, looks in for the sign, and takes a deep puff from a sizeable Cuban cigar. He throws a fastball down the heart of the plate, and I whistle a line drive inches from his famous visage for a single.

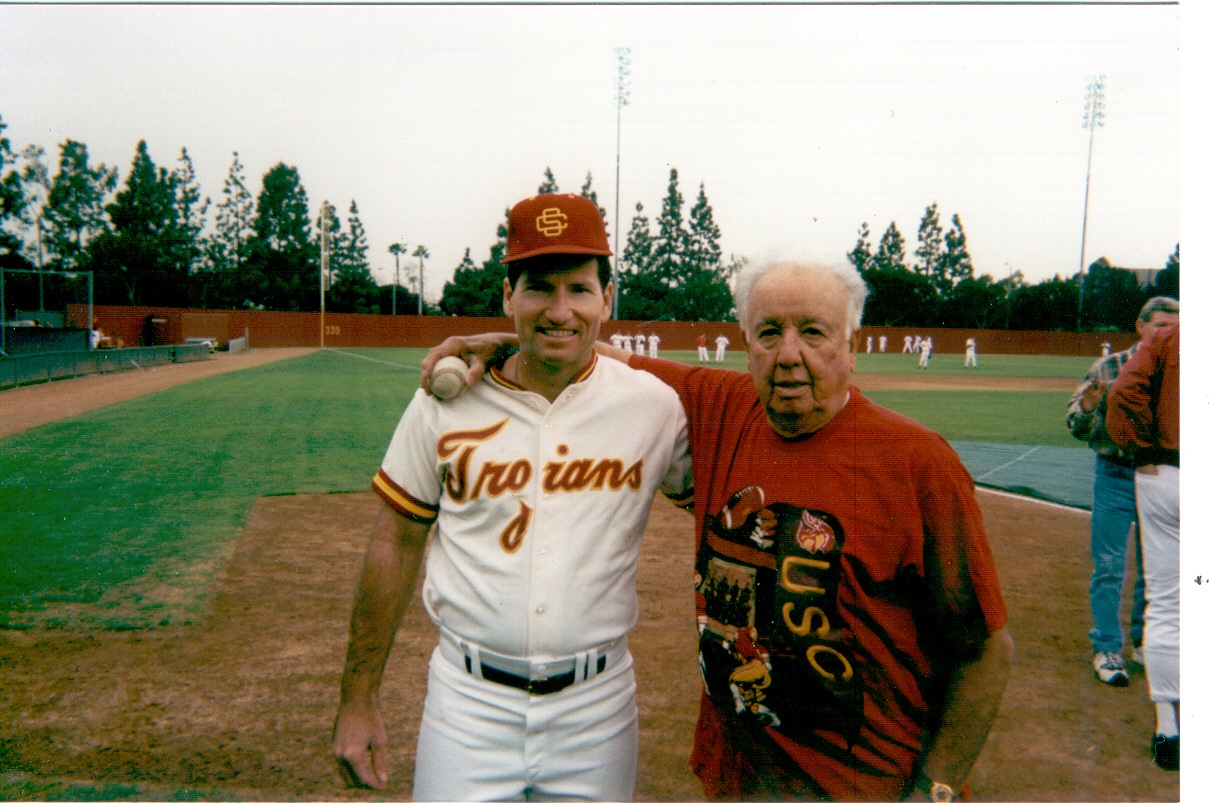

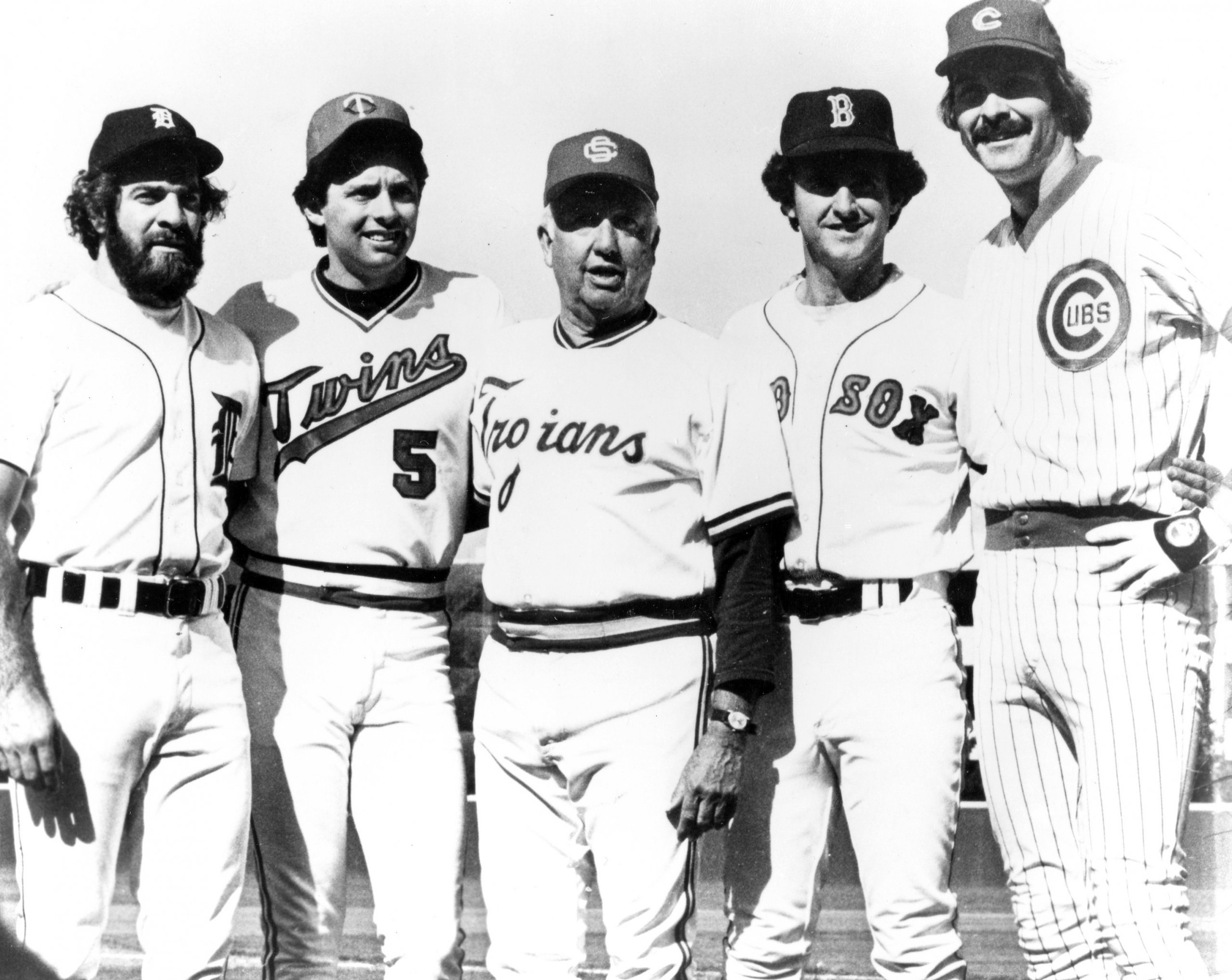

This was no dream or fantasy—just one of the Hollywood Celebrity Games that Coach Dedeaux arranged between the icons of the film and television industries and alumni of the University of Southern California (USC) baseball program. When I played outfield for Dedeaux in 1974–1976, mixing with the rich and famous was commonplace. Other stars who typically showed up for a celebrity event or ballgame were John Wayne, a USC football player in the 1920s when he was known as Marion Morrison, Tom Selleck, who played basketball at USC in the 1960s, and Mickey Mantle, the New York Yankees Hall of Famer who hit two of his longest tape-measure home runs in a 1951 exhibition game against the Trojans at Bovard Field on the USC campus.

I met Mantle when he suited up in his Yankee pinstripes to play in the 1975 celebrity game, seven years after his playing career had ended. Casey Stengel, a mentor and later a close friend of Dedeaux’s, was a frequent spectator at our Saturday conference games until his death in 1975. But competing against and talking with icons such as Jack Lemmon and John Wayne was only a part of what made playing for Rod Dedeaux a magical experience.

I met Mantle when he suited up in his Yankee pinstripes to play in the 1975 celebrity game, seven years after his playing career had ended. Casey Stengel, a mentor and later a close friend of Dedeaux’s, was a frequent spectator at our Saturday conference games until his death in 1975. But competing against and talking with icons such as Jack Lemmon and John Wayne was only a part of what made playing for Rod Dedeaux a magical experience.

Walking onto historic Bovard Field as a freshman in 1972, I was thrilled to be a part of collegiate baseball history. In his 45-year career at USC (1942–1986) Dedeaux compiled 1,332 wins, 571 losses, 11 ties—a Division I record that stood until 1994, 28 conference championships, and 11 College World Series championships, including five straight 1970–1974. He coached more than 50 future major leaguers, including Fred Lynn, Tom Seaver, Mark McGwire, Dave Kingman, Roy Smalley, and Randy Johnson. After World War II, he was a primary factor in re-establishing connections between USand Japanese baseball, and, in the 1980s, in establishing baseball as an Olympic sport. All the while he was building a highly successful trucking line, Dart Transportation, Inc. This article examines a few of the reasons why in 1999 Collegiate Baseball magazine named Rod Dedeaux the Coach of the Century and why his former players feel a bond with him that endures to this day.

Part of Coach Dedeaux’s genius was using every available resource to benefit his teams. His drills stressed the essential fundamentals of the game. He often told us that “taking infield” had become a lost art, stressing that fans would come out early to the College World Series games just to watch the Trojans take infield practice. About 45 minutes before the start of a game, Rod would take a fungo bat—he was superb at hitting fungoes—and hit to each infielder. After fielding a grounder and throwing to first, the player would cover his base to receive a throw from the catcher. He would then return the throw or toss the ball to a player at another base. Dedeaux would frequently yell, “Get rid of it; get rid of it!” reminding us that it was essential to make the transition from glove to bare hand and throw the ball as quickly as possible. “Move your puppies, Tiger!” he shouted frequently, reminding us to move our feet with quick short steps before making a throw. When USC “took infield” it was with a very flashy style and beautiful to watch. For whatever reason, the professionals quit the tradition years ago, and it is rare for college teams to “take infield” with the quickness, flair, and efficiency of the Trojans teams of the Dedeaux era. Coach Dedeaux put plenty of pressure on us to excel. He believed that if you could handle the stress he put on you during practice, you’d find it easier to handle when you were playing in front of 20,000 people in Omaha, Nebraska, at the College World Series. It was “taking infield” with the intensity that Coach Dedeaux demanded that prepared you for the pressure of big-game situations.

Being physically prepared was only part of Dedeaux’s teaching. He once said, “I always felt that the game was a lot more than just a bat, a ball, and a glove. The mental side is so important. And I always believed in doing everything right, whether it be on the field or off the field.”1

Coach believed in learning from others’ mistakes, so that you could avoid making them yourself. One of his favorite expressions, “Never make the same mistake once,” wasn’t asking his players to be perfect but to be closely observant and wise. He called all of us “Tiger” and expected us to be “in the game” at all times. When Coach Dedeaux corrected a player after he returned from the field to the dugout, the player would often defend himself by saying, “I thought—”

Coach believed in learning from others’ mistakes, so that you could avoid making them yourself. One of his favorite expressions, “Never make the same mistake once,” wasn’t asking his players to be perfect but to be closely observant and wise. He called all of us “Tiger” and expected us to be “in the game” at all times. When Coach Dedeaux corrected a player after he returned from the field to the dugout, the player would often defend himself by saying, “I thought—”

Dedeaux would always interrupt with, “Tiger, don’t think. You’ll hurt the ballclub.” Throughout my life I’ve realized that so much of the time we are better off staying in the moment and reacting rather than analyzing and thinking too much.

Dedeaux understood that bad bounces can happen, but considered a poorly thrown ball a mental mistake. While most coaches would consider an errant throw to be a physical error, Coach Dedeaux believed that, if you moved your puppies properly, you would always throw accurately. He kept a fine book for mental errors. Base-running mistakes, errant throws, throwing to the wrong base, and missed signs were considered mental mistakes. The most expensive was the first mental error of the day ($1.00); subsequent fines were 25 cents. Coach figured that if no one made the first mental error, we would play a perfect game. Like most college students, we were short on funds, so it behooved us to learn to do things the right way.

Dedeaux’s teams were not just mentally prepared. We were mentally tough. He was highly skilled in the art of bench jockeying—the ability to heckle your opponents from the dugout with a diverse array of put-downs without using profanity. (In today’s vernacular it’s called trash talking; this type of banter is no longer allowed in college baseball.) Certainly our opponents were no shrinking violets when it came to bench jockeying, but no team was as good at it as the Trojans.

While many thought this type of behavior was poor sportsmanship, Coach saw it as gamesmanship that we could use to gain an edge. (Still, Dedeaux had his limits. Late in the game, if we were far ahead, he would exclaim in his deep voice, “Let ’em die, Tigers,” a signal to not rub any more salt in the wound of our opponents.) If an opposing player had a big nose, we might holler, “What would you rather have, a million dollars or a nose full of nickels?” Or, if he carried some extra weight, he was likely to hear, “Don’t go near the ocean, you’re liable to get harpooned!” Not only did this serve to distract opposing teams, more importantly, it kept the players on the bench actively involved in the game. Perhaps the Trojans’ finest moment in bench jockeying came during a crucial game in the playoffs for the CWS in 1973. As Dedeaux recalled2:

Dave Winfield was pitching a great ballgame for the University of Minnesota. Going into the bottom of the ninth, the score was 7–0 against USC, and we’d only had one hit, an infield single. I’ve not talked much about this before, but Minnesota was doing a lot of hot-dogging, which made us mad. And a lot of people felt we were in trouble, what with the lead and Winfield pitching. … But we were a disciplined team, and you had to credit the patience of our batters, who had made him throw a lot of pitches. … He was up to some 150-odd pitches, and yes, our guys were counting, helping him to realize what he was doing. They were putting a thought in his mind. They’d say, ‘152, 153…’ And he’d look at his arm. But he was tiring, there’s no doubt about it. So they took him out, and he moved to the outfield. Well, we rallied—and they talked to Winfield about coming back in to pitch, but he didn’t do it. And we beat them. … They say this may have been the greatest come-from-behind victory in the history of college baseball.

One of the reasons Coach Dedeaux was so beloved by his players was that it was so much fun to play for him. Whether it was in the locker room, on the field, or at a banquet, he was a fabulous storyteller and comedian. He had a resonant voice that took command of any setting. I am pretty sure he developed his biting sense of humor from his close friend, Casey Stengel. Both were long-time residents of Glendale, a suburb north/northwest of downtown L.A.

Coach Dedeaux encouraged fun and a light-hearted approach that he felt kept us loose and relaxed under pressure. One of his favorite routines was the singing of “McNamara’s Band” after each win. A former player from the 1950s, Bill Doyle, told me how this tradition began. Rod was a big fan of the singer Dennis Day, a regular on the old Jack Benny Program on CBS-TV, and loved Day’s version of “McNamara’s Band.” He decided to make that our signature song. When Coach entered our locker room after a win, he would scream, “That Trojan horse is out in front and they’ll never catch us! When you sing it, sing it loud! ‘Oh, me name is McNamara, I’m the leader of the band. Although we’re few in number, we’re the finest in the land …’” We were loud and celebratory, though no one would ever have confused us with the Mormon Tabernacle Choir.

I have been teaching teenagers at Duarte High School, near Pasadena, for the past 33 years. For the last ten years I have incorporated a “Friday” song, similar to Coach Dedeaux’s “McNamara’s Band.” I play Loverboy’s “Working for the Weekend” for my students to celebrate that we made it to Friday. They absolutely love it! Believe it or not, each senior class requests that the song be played during the prom, and they make sure that I stick around to dance with them. It shocks me that they get such a charge out of it, but I must thank Coach Dedeaux for the idea.

Baseball has a tradition in which rookies are made to do something unusual. Back in his youth at Hollywood High School, Dedeaux had acquired a red wig from the drama department. Years later, as coach of the Trojans, he decreed that a player on his first road trip had to wear the hideous-looking wig at the airport in a way that would cause his teammates to break into laughter. Tom Seaver did, Billy [“Spaceman”] Lee did, and then there was Randy Johnson. As Dedeaux recalled, “It was on a Sunday afternoon, at LAX, I think, with a crowd around. Johnson comes sliding down the chute with a baggage tag, just stretched out, and that long body going around and around, with the wig on. Well, it did shake things up.”

I once asked Marvin Cobb, who earned two championship rings as a defensive back for Coach John McKay’s football team and two championship rings as shortstop/second baseman for Dedeaux, about what made Dedeaux so good. “He was far and away the greatest coach I have ever had,” Cobb replied, adding that it was not only all the championships. “It was the psychological aspects of baseball that have translated into all the facets of my life.” Marvin’s favorite maxim of Dedeaux’s is, “Just the way we like it!” “Number One,” as the players affectionately called our coach, used this expression any time the weather was bad, the odds were against us, or we were dealing with a very difficult situation. Ever the master psychologist,

Coach Dedeaux never let us grow negative about anything. Cobb pointed out that there have been countless challenges throughout his adult life when this outlook helped him to succeed.

Coach Dedeaux was masterful at making you a tough competitor and person. But if he made you the butt of a joke, he would soon point out the positives about your game. While I was initiated with the “red wig in the airport” treatment and endured some teasing by Coach Dedeaux, he made up for that many times over with some of the most genuine compliments I have ever received. At the beginning of 1977, he introduced me as head coach for our junior varsity team. He told our new players that when I came to USC he didn’t see how I’d ever be able to play for our varsity. Through hard work and determination, I became the cleanup hitter. As Coach Dedeaux said, “That’s really saying something.”

*****

Most of us players thought we were training under Coach Dedeaux to become major leaguers. In reality, we were all serving an internship for life, for in addition to making great baseball teams, he was, more importantly, passing on his wisdom and experience so that we could thrive in any setting. In 2008 the USC Baseball Alumni Association was organized to support the university’s baseball program. That’s the official reason it exists. Unofficially, most of its members, who are now in their fifties, sixties, and seventies and played for Coach Dedeaux, want to keep his memory alive. All of us treasure being with those who loved him as much as we did. The time we spent playing for Coach Dedeaux lasted only a few short years, but what made him so fabulous for those fortunate to have been under his supervision is that his emphasis on mental toughness, optimism, and fun translated not only to winning baseball games but to succeeding in life.

BOB LEACH played first base for the 1972 Sierra High School baseball team, a CIF semi-finalist. At the University of Southern California, he was a member of the 1974 NCAA Champion Baseball team as well as the 1975 and 1976 teams. In 1980 he was head coach of USC’s junior varsity as well as assistant baseball coach at Duarte High School, where he has taught for 34 years. He frequently attends USC baseball games and plays in the annual alumni game, collecting a single and double in the 2010 contest. Each summer he visits the wonderful “retro” ballparks around the country. He is the author of the recently published biography of “Rod Dedeaux: Never Make the Same Mistake Once”.

Notes

1 Rod Dedeaux, personal interview, Dan and Jean Hastings Ardell, March 6, 2002.

2 Rod Dedeaux, personal interview, Dan and Jean Hastings Ardell, March 6, 2002.