Origin of the Modern Pitching Win

This article was written by Frank Vaccaro

This article was published in Spring 2013 Baseball Research Journal

Ray Scarborough holds the first modern assigned win in baseball history, April 18, 1950.

A recurring question among SABR members in recent years involves the first modern win: when was the first win awarded to a starting pitcher incorporating a league-mandated rule requiring the five-inning minimum standard?

On the SABR-L email list, historian David Nemec is often quick to reply that the standard appears in the rulebook in time for the 1950 season. That makes Washington pitcher Ray Scarborough’s opening day victory on April 18, 1950, the first modern assigned win in baseball history, a game in which Harry Truman, some might say, threw out the “first pitch.” Of course, Scarborough wasn’t the first pitcher to win a game after pitching five innings: baseball history is chock full of five-inning wins dating back to the old National Association. But of those, Scarborough was the first pitcher to take a shower knowing full well that the “win” was in his pocket, so to speak, provided the Nationals never lost the lead. The win seems easy to understand and even academic, yet it was the culmination of a long, tortured history since the stat was invented.

On May 9, 1872, Boston’s Al Spalding was relieved after four innings in a 20–0 romp over the Brooklyn Eckfords at Brooklyn’s Union Grounds. Spalding had a no-hitter and a 17–0 lead when he was relieved, but amazingly still did not receive credit for the win after the game. Was this baseball history’s first incidence of a no-decision and a five-inning minimum standard? No. Wins for pitchers had not yet been invented.

Fans and players of 1872, and even Spalding himself, would have likely been bewildered by the proposition that pitchers be credited with wins and losses. Actual wins—or so it would be argued into the twentieth century—could belong to any member of the team: the first baseman who got the game-winning hit or the center fielder who made a game-saving catch. Also, the art of pitching had not yet developed to elevate the pitcher much over the simple cricket feeder. Even Spalding’s no-hitter was likely considered merely a coincidence of good fielding. No sophisticated separate stats for pitchers existed. Additionally, with normally one pitcher per team, individual win-loss records deviated little from team records and, at that time, would have been redundant.

The win was invented in 1884 by Henry Chadwick and he published National League individual totals in the 1885 Spalding Guide. The practice did not catch on. The loss came later. On July 7, 1888, The Sporting News for the first time published win-loss records, and only then after the following disclaimer:

It seems to place the whole game upon the shoulders of the pitcher and I don’t believe it will ever become popular even with so learned a gentleman as Mr. Chadwick to father it. Certain it is that many an execrable pitcher game is won by heavy hitting at the right moment after the pitcher has done his best to lose it.

Free player substitutions were not allowed in baseball until 1889, but even then, only one or two free changes were permitted per game after completed innings. In 1890 our modern player substitution rule was adopted but managers didn’t utilize it to its full capacity. Prior to these rules, a pitcher could be removed only by injury or by switching him to another position. In Spalding’s 1872 game, he was switched to center field and played the last five innings there. Box scores have him as “cf” only.

So it was relatively easy for Chadwick to assign wins and losses in this period, and if he had any existential difficulties making these assignments, he didn’t reveal them in print. In the 1890 Guide he advises, “Where two pitchers took part in a match on one side we credit the victory, or charge the defeat, to the pitcher who pitched in the most innings.” That’s sort of a five-inning minimum, except that the timing of run support is ignored. That’s the same rationale that made Spalding a center fielder in a near no-hitter.

So existential difficulties did arise from the get-go. When The Sporting News began listing the win-loss records of their hometown St. Louis pitchers in August 1888, rookie Jimmy Devlin, who made no starts in August and September, alternated weekly between having a record of 5–3 and 5–2. The only game that he was relieved in came on the Fourth of July, when he was knocked out in the seventh inning with a 2–11 deficit. A clear loss by any measure? Not in 1888.

The slightly senior Sporting Life was more distanced from win-loss records. In their November 14, 1896, issue a list of the NL’s top winning pitchers came with this disclaimer: “though technically they did not win or lose, as most of the games can be charged to fielders behind the pitchers.” That list shows a three-way tie at 30 wins between Frank Killen, Kid Nichols, and Cy Young, yet today’s encyclopedias show Young with 28 wins. Any assumption that today’s encyclopedias “agree” with the 30 wins of Killen and Nichols highlights one important problem in reconciling pre-1920 pitcher records: agreement in victory or loss totals never guarantees that the same games are counted.

By the late 1890s, Chadwick, editing the Spalding Guides, used different formats for his pitcher games won, perhaps because his stat was not catching on. Guides listed “Games” and “Per Cent of Victories”—rather than wins—and this became the standard for a generation, leaving fans the task of fudging and multiplication to figure out actual games won. This was the principal reason Christy Mathewson’s 373rd victory went uncounted until 1946—much to the chagrin of the bed-ridden Grover Cleveland Alexander—as recounted by Joe Wayman in the 1995 Baseball Research Journal. In the 1900 Guide, Chadwick listed the NL’s top winners counting only their records against first division teams. It was a nice SABR-like twist.

NL secretary John Heydler issued guidelines to official scorers in 1916 that specified a starter had to pitch “at least the first half of the game” to get a win.

In 1903 official scorers likely began the practice of placing a “W” or an “L” alongside pitchers’ names on score sheets. That’s the year new NL president Harry Pulliam hired John Heydler as a personal secretary at the recommendation of Nick Young. The 33-year-old Heydler had impressed Young as a local Washington area semipro umpire who kept his own major league statistics. Young had also used Heydler sometimes as an NL ump for the better part of three seasons up to 1898. Heydler immediately organized NL stat-keeping, and corrected the previous season. Previously the NL was run by a “board of directors” headed by John Brush, a disorganized group said to be too distracted by the NL-AL war to give stats their due consideration.

It’s possible official scorers assigned wins and losses in 1901 or 1902, but those original sheets have been misplaced for many years. In any case, after each season, league secretaries summed up each pitcher’s win-loss record for the Spalding and Reach guides. League secretaries and league presidents also, from time to time, began stepping in and “correcting” a scorer’s awarded decision. Chadwick, for his Spalding Guides, continued determining his own winners and losers for each game, even though, shockingly, he was rarely in attendance to see the pitchers perform.

Frank J. Williams’s landmark essay “All the Record Books Are Wrong,” in SABR’s 1982 inaugural issue of The National Pastime, catalogues the methods official scorers used to assign decisions during the Deadball Era. Williams reveals 11 methods of assigning wins and losses in this period, and is kind to scorers of the time by referring to them as “eleven scoring practices.” It was the Wild West of official scoring and many of these practices are flat-out contradictory. Often, the assignment of wins and losses hinged on an official scorer’s informal post-game poll of sportswriters sitting next to him. Bias toward more popular or established pitchers might also have existed.

It is due to Williams’s work that today encyclopedias agree on 1901–1920 pitching records, but even he acknowledges that “a couple of more practices may yet emerge.” One is the Fielder Jones rule of 1914. With Jones sometimes using four or five pitchers in a game, official scorers required that a pitcher throw at least one pitch to get a win. The Federal League didn’t enforce such a rule, so on September 19, 1914, Jim Bluejacket of the Brookfeds got the majors’ first no-pitch win.

Christy Mathewson’s 373rd career win went uncounted until 1946.

Changes in baseball were turning Chadwick’s art of determining winners and losers into conundrums of logic. On April 26, 1894, it can be argued that Baltimore manager Ned Hanlon made the first pitching change “on a hunch” when he replaced the uninjured left-hander Bert Inks with the right-handed Kirtley Baker, in the bottom of the sixth inning hosting Boston, with a 7–5 lead. One can also argue that on June 15, 1907, John McGraw pulled the first double-switch after he had Roger Bresnahan pinch hit for Joe McGinnity in the top of the eighth inning at Pittsburgh. And on May 13, 1909, managers Joe Cantillon and Billy Sullivan, of the Nationals and the White Sox, respectively, engaged in the kind of late-game, lefty-righty pitcher and pinch-hitter matching that would make a 21st century manager proud. Alongside these events, relief pitcher use was perennially on the rise in the major-league arena. Pressures from all these directions came to a head 101 years ago thanks to two pitchers: Rube Marquard and Walter Johnson.

The New York Giants’ Marquard was given credit for a 19-game winning streak from season’s start on April 11 to July 3, 1912, and the Senators’ Walter Johnson was given credit for a 16-game winning streak from July 3 to August 23, 1912. Contradictory and counter-intuitive scoring practices occurring during these streaks created a sense of public outrage that swelled as the pennant races drifted into blowouts. Frank Williams provides the details in his essay, but suffice to say Johnson was credited with his 13th consecutive win in a circumstance similar to Marquard’s no-decision when his streak was only two victories long. Marquard’s streak hinged on the question of giving a pitcher a no-decision when the score became tied after he exited, and the proper crediting of runs in an offensive inning when the pitcher is pinch-hit for. The big Johnson issue, occurring when his streak was 16 games long, clarified that inherited runners are, in the calculation of earned runs, the responsibility of the pitcher who put them on base. But immediately after the August 26 game, American League president Ban Johnson went against this latter notion, raising the ire of every Washington fan, and saddling modest Walter with a loss that ended his winning streak.

Heavily criticized, Ban Johnson reacted like the kid in the sandbox with all the toys: he removed wins and losses from American League tabulations and released no pitcher win-loss records for the next six years. Fortunately for future generations, official scorers still marked score sheets with W and L. The National League took a more professional tack. League president John Tener was above the minutiae of pitchers’ decisions, leaving his competent league secretary John Heydler to issue bulletins to official scorers. These contained guidelines as to how wins and losses would be awarded. The most famous of these bulletins was released to the press April 1, 1916, ten days before the start of that season.

The first three rules in this bulletin, in rapid fire succession, clarify and make modern the three issues raised by the Marquard and Johnson streaks of 1912. The fourth rule is the earliest official hint of a five-inning minimum for starting pitchers, albeit with an exception for pitchers who have a big lead:

Do not give the first pitcher credit for a game won even if score is in his favor, unless he has pitched at least the first half of a game. A pitcher retired at close of fourth inning, with the score 2–1 in his favor, has not won a game. If, however, he is taken out because of his team having secured a commanding and winning lead in a few innings, then he is entitled to the win.

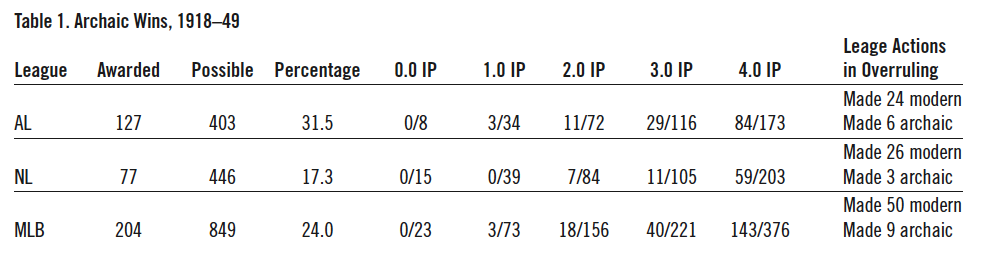

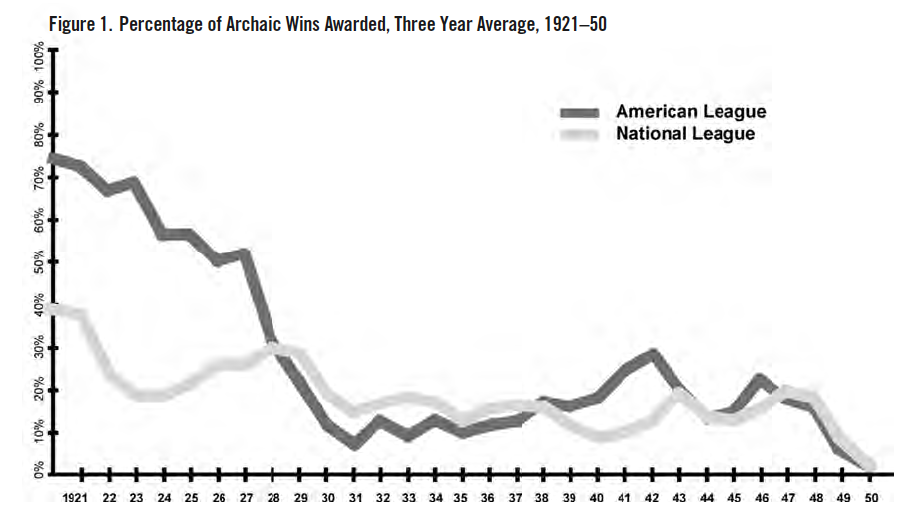

This bulletin tightened up National League win-loss decisions in 1916, and spilled over into American League practices the next season. In 1918 win-loss information became more commonly dispensed, and The Sporting News box scores begin listing winning and losing pitchers in their May 9 issue. (However, periods do exist, until early in 1925, when The Sporting News boxes omit this information.) By 1918, almost everything about awarding wins and losses was modern. Scorers had only to consider “commanding and winning leads” in awarding wins to starting pitchers with fewer than five innings of work. Over the next 32 years two opposing practices evolved to bring us to the 1950 rule. On the one hand, wins awarded in low-inning starts were phased out even when “commanding leads” existed, while on the other brand new excuses came into play allowing wins in low-inning starts. Between 1918 and 1949, Retrosheet shows 849 games in which a starting pitcher could have gotten a win without pitching five innings. In 205 of these games, 24 percent, the starting pitcher did get the win. The figure might have been 29 percent, but league secretaries overruled official scorers in 39 games, nudging the habits of scorers towards our modernity. In 1918, for example, there were 23 games of this type of which 16 saw starting pitchers get wins, 70 percent. In 1949 there were 30 such games with four of them becoming wins for starting pitchers, 13 percent. We’ll call these archaic wins. For a year-by-year graph of the penchant of major league official scorers to award archaic wins, between 1918 and 1949, see Figure 1.

(Click image to enlarge.)

John Heydler ascended from NL secretary to NL president in 1918. By 1923, the National League was honoring the five-inning minimum almost 70 percent of the time. The American League, still coddled by founder Ban Johnson, honored the five-inning minimum only 9 percent of the time. When Ban Johnson retired in 1927, the NL honored the five-inning minimum 100 percent of the time (10 out of 10) over the AL’s 37 percent (7 out of 19). In Ernest Barnard’s first full year at the AL’s helm, 1928, both the NL and the AL awarded modern wins 67 percent of the time (8 out of 12). So no surprise here, besides the fact that the NL regressed on the issue. Ban Johnson didn’t approve of the five-inning minimum and worked against it. Barnard actually took over running the AL mid-July, 1927. Up to that time, the AL honored the five-inning minimum 23 percent of the time. During the second half of the season the AL honored it 50 percent of the time.

One of Barnard’s first moves as AL president was to overrule the official scorer who gave George Pipgras a win July 8 for being knocked out in the bottom of the third inning at Detroit with a 6–2 lead. That occurred in the last full day of Johnson’s stewardship. Pipgras was so well rested that he pitched the next day—the day Barnard became AL president—and Pipgras received another win despite being knocked out in the bottom of the fourth inning. This second archaic win Barnard let slide. After all, the 19–7 final score was pretty commanding. Barnard established a 4.0 inning minimum in the American League when Heydler’s 5.0 inning minimum was being accepted in the National League. These scoring practices came to a head in the Worlds Series where different standards applied to different players in the same game. Good research by SABR’s Warren Corbett identified George Earnshaw as a benefactor of this bipartisan scoring truce in game two of the 1929 Fall Classic. Earnshaw pitched four innings and won “under American League rules.”

The retirement of Ban Johnson remains the single greatest hurdle cleared towards the acceptance of a five-inning minimum. But as time marched towards Ray Scarborough’s first 1950 start, official scorers began invoking any of five different exceptions, when events warranted, for the assignment of low-inning wins. That makes the study of the first modern win an endeavor with a lot of moving parts. Here are the exceptions official scorers used:

THE INJURY EXCEPTION

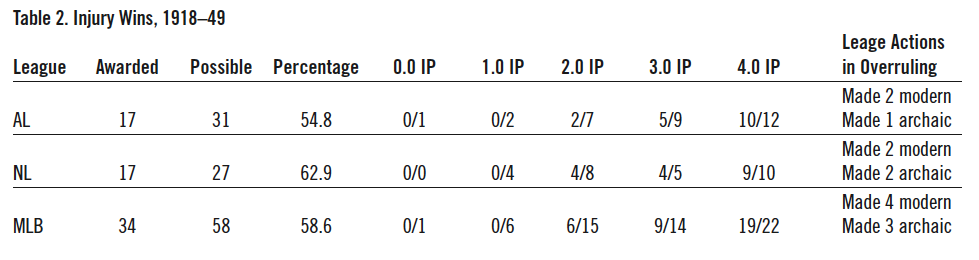

The principal exception used by official scorers from the Deadball Era all the way to 1949 was the injury. Any pitcher injured was released from any minimum innings requirement—most of the time. Of 58 post-1917 games in which the starting pitcher had the lead but was injured before completing five innings, 34, or 59 percent, went for wins.

Frank Williams identifies this tendency under the fourth of the eleven practices. But after April 28, 1930, this injury exception takes on a life of its own. That day Clarence Mitchell received the first sub-4.0 inning injury exception win since July 31, 1923, when, coincidentally, the very same Mitchell had been carried off the field in the fourth inning after a collision with first baseman Walter Holke. Mitchell’s 1923 win seemed to be the last of its kind—until Mitchell’s 1930 win rekindled the practice.

Forty-seven potential injury wins exist between 1930 and 1949, and 27 are stamped with major league W’s. Injury wins accelerated in use as 1950 approached. During the 1948 and 1949 seasons it was granted a whopping 90 percent of the time, when events warranted. Descriptions of these games run the gamut. Carl Hubbell got one when he slipped and fell on a play (June 10, 1934), Johnny Allen got one when he wrenched his back (September 15, 1936), and Lefty Grove left a one-sided game against Detroit (July 14, 1938) when his hand became numb, a chronic issue from which he suffered. All got wins. Two-time winners in this category include Lefty Gomez and Dutch Leonard. On the flip side, Bob Feller and Sad Sam Jones are two-time non-winners. The difference in these games? Hard to tell.

Consistency, lacking in the awarding of injury wins, was lacking in the awarding of all archaic wins. Some starters in this 32-year period did well, others didn’t. Eddie Rommel had the greatest luck in being awarded wins: he won nine against two no-decisions. Ben Cantwell and Rosy Ryan both won six with one no-decision. Firpo Marberry, his relief work so often unrecognized in the 1920s, would have won fifteen extra games had a five-inning minimum come sooner. Instead he won four. Ralph Branca, Ray Starr, and Johnny Vander Meer each had over five no-decisions in low-inning games that could have gone for wins.

Schoolboy Rowe pocketed one on July 19, 1939, when he took a Mickey Vernon line drive on the knee. Earlier that day, Al Munro Elias, the compiler of stats for both leagues and baseball’s go-to guru on the art of win assignment, suffered a stroke that removed him from day-to-day tabulations. He passed away a few days later. Gone with Elias was the concept that “If a pitcher couldn’t lose, he shouldn’t win,” one that worked against the vultured wins we see relievers obtain today.

Elias apparently also kept injury wins in check, because after he left things got out of control. Braves starter Al Javery left a game early with chest pains, and got a win (August 9, 1944). Virgil Trucks left early with a one-run lead and indigestion. He got the win (June 5, 1946). Four days later Ken Heintzelman took a Sid Gordon liner on the jaw: alas! He got no win. Any pitcher who exited a game early with a lead simply rubbed his arm and looked up endearingly to the scorer’s booth. Blisters, pulled thighs, headaches, sinus trouble, back aches, you name it: pitchers were eager to discuss these sufferings with beat writers. The Pirates’ Elmer Singleton had a shot at a win, which went to relief pitcher Tiny Bonham (April 30, 1947). The official scorer, Stan Baumgartner, came into the clubhouse after the game and interviewed players regarding a possible injury. He switched the win to Singleton, but was on the fence and switched again to Bonham when he sent his score sheet to the league. Singleton didn’t know that and bought beers for the whole club to celebrate what he thought would be his first win in two years. As far back as 1930, A’s starter Rube Walberg lost a win when manager Connie Mack told the official scorer that Walberg hadn’t been injured, but instead had been removed on a hunch (July 12, 1930). Sports editorials lambasted the lack of hard and fast rules on the subject.

A record six injury wins were awarded in 1948, including Dutch Leonard receiving the majors’ last two-inning injury win (June 30, 1948, as noted above). The Braves’ Glenn Elliott received the majors’ last three-inning injury win (September 1, 1948) after he collided with brawny Ted Kluszewski: knowledgeable fans might consider this a fair application of the exception. It was Elliott’s only appearance of the year, so his season stat line showcases the injury exception. The Reds’ Ewell Blackwell received the last four-inning injury win (July 18, 1949), indeed the very last injury win ever awarded. Not too sur-prisingly, Blackwell developed a stomachache after giving up back-to-back hits in the fifth inning. The official scorer gave the win to reliever Eddie Erautt, but the league changed it to Blackwell. It’s a rare case of the official scorer being more chic than Frick.

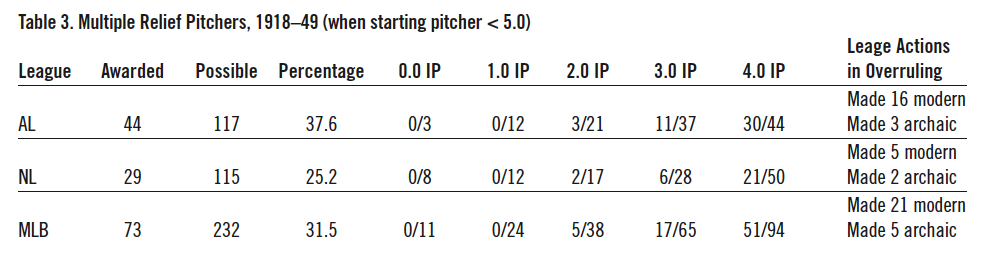

Only three games in this study show ejection as the cause of a starting pitcher departing. In all three cases, wins went to middle relievers. Unlike the Deadball Era, pitchers after WWI were held responsible for actions that led to ejection. For example, in the most recent of these three games, the Cubs’ Claude Passeau was ejected for shoving umpire Lee Ballanfant (July 16, 1939). No argument seems to have been put forth that Passeau was the victim of his own Cajun temper. I have not actually seen or heard of this rule, but looking at the data, it’s clear: if two pitchers appear in a game where the starting pitcher has not pitched five innings, the starting pitcher got the win 17 percent of the time; if three or more pitchers appear in a game, the starting pitcher got the win 37 percent of the time.

That harkens back to the “bulk of the good pitching,” the fifth scorer’s practice outlined by Frank Williams. Three innings for a start looks shabby when a reliever has gone six, but looks better when two other relievers each go three innings. These types of wins, not considering injuries or any other excuse, were a popular scorer’s option until 1930. From 1918 to 1929 we see 39 such wins, about three a year. From 1930 to 1949 we see 18, less than one a year. This change of behavior in 1930 is abrupt, and follows a pattern of leagues overturning official scorers on this issue which begins in 1924. Game reports for two of these victories reveal fuzzy logic. For a June 5, 1924, win, the Washington Post notes that Curly Ogden got the nod “because he left the box with the Nationals on top and the score was never tied after his departure.” On May 22, 1940, Mel Harder got the win because he “stayed long enough to get credit.” A Brooklyn 9–6 win at Philadelphia, May 2, 1948, seems to be the impetus for the discarding of the multiple reliever rule in awarding wins. Each of three bad pitchers could have won, so NL president Ford Frick stepped in immediately after the game and announced the winner, and, for that matter, the loser. A few weeks later, on June 12, Cleveland’s Bob Muncrief benefits from this practice for the last time in big league history.

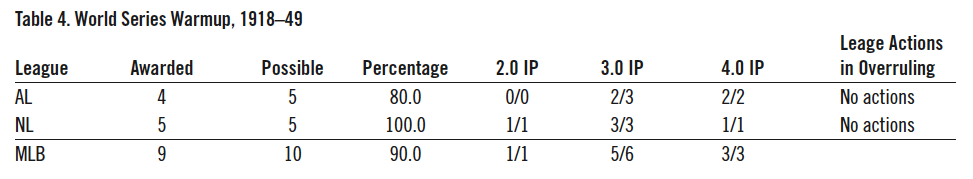

THE WORLD SERIES WARM-UP

The World Series warm-up involves the use of a starting pitcher after the pennant has been clinched. The pitcher must go a few innings and be removed with the excuse given that he is getting ready for the World Series. No matter how many innings the starter went, it was only required that he leave the game with the winning lead. Of course there have been hundreds of games in which pitchers were warmed up for the postseason, but there were only 13 during this study period in which the starter had the winning lead, and left before the fifth inning. In those 13 instances the starter got the win 12 times.

The first World Series warm-up was pitched by the White Sox’s Doc White, October 5, 1906, but he was removed after seven innings. In 1910, 1911, and 1912, the Cubs’ Orval Overall, the A’s Jack Coombs, and the Giants’ Jeff Tesreau, respectively, pitched the next three such warm-ups. However all three were removed after pitching the fifth inning, and only Overall had the winning lead. On October 2, 1913, Christy Mathewson was removed after four innings with a 2–1 lead in a meaningless game: history’s first official win in this category.

It’s a small category of victories, but it’s real. On September 30, 1934, Tigers teammates Alvin Crowder and Tommy Bridges picked up warm-up wins in both games of a doubleheader hosting the Browns. Only four warm-up wins follow: the Giants’ Hal Schumacher in 1937, the Reds’ Bucky Walters in 1940, the Yankees’ Tiny Bonham in 1943, and finally the Braves’ Nels Potter in 1948. Schumacher hit a game-winning three-RBI home run in his short 1937 win, and Potter’s victory was the last two-inning victory in MLB history.

The Yankees’ Lefty Gomez, pitching on October 2, 1938, is the only pitcher in this era to be denied a World Series warm-up victory. Gomez allowed one hit, and left after three innings with a 1–0 lead at Fenway Park. Steve Sundra pitched six relief innings to complete the win, the only time a reliever went that long in this type of win.

A 14th win in this category might include Van Lingle Mungo’s September 27, 1936, start. Brooklyn manager Casey Stengel announced before this end-of-season game that Mungo would pitch only two innings. This he did, leaving with a 6–0 lead while padding his season total in strikeouts to 238. He got the win, but Brooklyn finished seventh, so what Mungo would have been warming up for is unclear.

THE SAVE WIN

Impressive work by a relief pitcher, in the general area of what we would today call a save, garnered 21 official wins during this period. Three of these appear in 1948, a record for the “save win,” and an indication that the practice was accelerating when the 1950 rule book was released. Almost immediately after the 1950 scoring change, the modern save as we know it was born, becoming an official statistic in 1969.

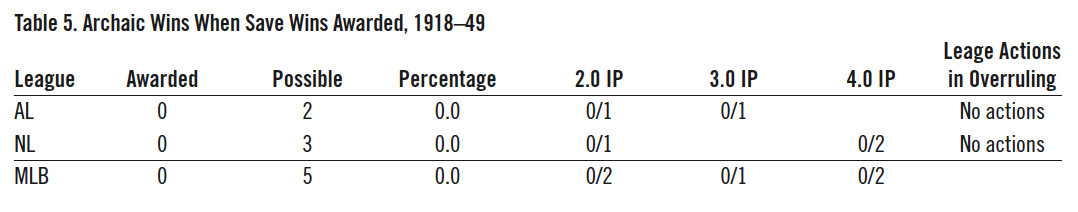

This is the third scoring practice as outlined by Frank Williams. However, “save wins” could be awarded regardless of how many innings the starting pitcher went, thus shedding little light on the evolution of a five-inning minimum. The 21 “save wins” occured in the 78,286 games played during this study, so it happened about two times every three major-league years, sharing the frequency of a celestial event. Additionally, of those 21 “save wins” only five occurred when the starting pitcher left before the fifth inning, thus only five intersect with the games of this study. The obvious is illustrated in Table 5: in none of the five games did the win go to the starting pitcher.

The three “save wins” in 1948 include Dan Casey’s three-inning bailout of starter Rex Barney in Brooklyn’s Opening Day victory; a win for Detroit’s Virgil Trucks, July 23; and another for a Brooklyn pitcher, Paul Minner, September 16. A fourth “save win” was awarded to Clint Hartung of the Giants, June 13, but rescinded by the NL a few days later. They doled it out instead to middle reliever Larry Jansen.

WEATHER-SHORTENED GAMES

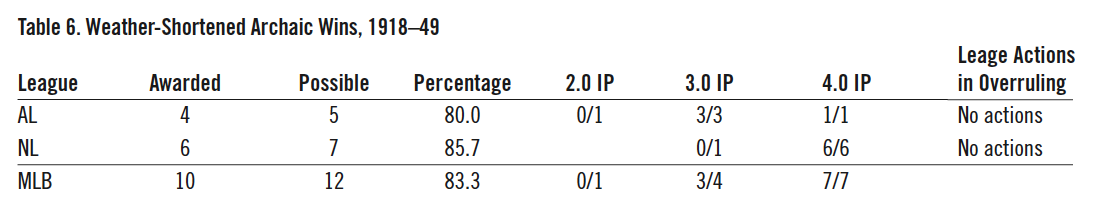

Twelve games in this study saw starting pitchers go two, three, or four innings in a game that went five or six innings. With two exceptions, the starting pitcher got the win per a scoring practice that actually survives to this day. The most recent four-inning victory in a rain-shortened game went to the Phillies’ Andrew Carpenter in 2009. Weather- and darkness-shortened games of seven or eight innings have a healthy percentage of archaic wins awarded: 45 percent. However, this pales in comparison to the 83 percent we see in five- and six-inning conquests.

The AL enforced a three-inning minimum while the NL looked for four innings in these ultra-short games and the two starting pitchers who did not gain wins in this category both fell shy of those milestones. The Cardinals’ Jim Hearn pitched 3.1 (7/5/1948) and the Browns’ Dick Starr pitched 2.2 (9/25/1949).

Wins in this category did not exist between July 10, 1949, and May 12, 1978, a span of nearly 30 years and over 45,000 games. So the 1950 ruling did affect weather-shortened wins for a generation, until Wilbur Wood received official scorer mercy for his 157th career win on that 1978 date. Larry Luebbers’ 1999 win was finally awarded late in the evening, October 3, when the game was cancelled.

Three of the last four pitchers to receive these wins never won again, their weather-shortened victory becoming their very last in The Show. Luebbers was the first of this cursed group; the Reds’ Chris Michalak also won late in 2006, and the Phillies’ Carpenter as mentioned. The fourth pitcher, CC Sabathia, won a 2001 game in this fashion in his tenth career start. He is still active and may yet join this group by bowing out with a rain-shortened win. It would, however, require him to become the first pitcher to gain two wins in this teensy category.

The post-1950 incarnation of the weather-shortened win is different only in that three-inning wins are disallowed. The last three-inning win in a weather-shortened game went to Washington’s David Thompson, September 19, 1948.

Unless he’d seen it in the 1885 Spalding Guide, which was unlikely, Old Hoss Radbourn probably never knew he won 60 games — or close to it — one season.

COMMANDING LEADS

After filtering out the excuses and exceptions of the study era, one is free to analyze the remaining 766 games for clues to the guidelines official scorers used in awarding archaic victories. Overlap does exist between groups—there may be multiple relievers in a game in which the starting pitcher is injured—so the quantity of starts when adding up all of these groups totals lower than expected.

One trend stands out: NL official scorers honored John Heydler’s 1916 bulletin. Remember, Heydler’s “commanding lead” guideline said that “a pitcher retired at close of fourth inning, with the score 2–1 in his favor, has not won a game.” Sure enough, no NL pitcher since won a game with a 2–1 lead and fewer than five innings of work. In fact, only two out of 139 starters won an archaic victory with a one-run lead. The Cubs’ Alex Freeman (September 9, 1921) and the Pirates’ Bill Swift (August 23, 1935), both won after leaving with 5–4 leads, but only because multiple relievers followed them. For the thirty-two years in the study period, Heydler’s guideline required NL teams to play for one run if the starting pitcher with a one-run lead was to get a win. This is the real reason that, to this day, the NL is known as a one-run league. It wasn’t because John McGraw loved to bunt. John McGraw abhorred the bunt.

Even two runs couldn’t guarantee you an NL win. Only seven starters out of 99 games received archaic wins with two-run leads, and six of those again took advantage of multiple relievers to win. Only the Phillies’ Pretzels Pezzullo, in his first career start (May 27, 1935), managed an archaic win with a two-run lead and one reliever. Pezzullo gave up nine hits in 4 2?3, leaving with the bases loaded. Euel Moore gave up three hits in 4 1?3 innings of shut-out relief, and left the game with the same 4–2 score he inherited.

Even for leads of three, four, and five, the AL handed out archaic wins by a 39–25 margin over the stingy NL, despite the fact that the NL had more occurrences of these potential archaic wins: 142–123. Only when leads were six or more did NL official scorers grant low-inning victories: the NL awarded 14 in 25 contests, while the AL awarded 9 in 26 contests.

The AL was simply not guided by commanding leads. Ban Johnson actually oversaw two archaic 2–1 victories handed out under his watch. They went to Washington’s Harry Harper (May 3, 1919) and the A’s Sam Gray (August 19, 1926). Harper went only two innings and the official scorer gave the win to the reliever, Ed Hovlik, but in complete defiance of the NL rule Ban Johnson overruled the official scorer and made sure Harper got the win.

American League archaic win awarding was more an art form. In the Ban Johnson era the AL out-awarded the NL 79-to-27. Once Johnson retired, the AL and the NL were practically on even terms and the AL out-awarded the senior loop, 23-to-22. Barnard’s four-inning minimum was ignored only twice in the late 1940s, when multiple relievers muddied the waters for two win assignments. Yankees’ pitcher Randy Gumpert’s first win after returning from World War II duty was the first of these (April 24, 1946) and the sore-armed Mickey Harris got the last (July 6, 1947). Harris was arguably the best of four Red Sox pitchers that day.

Snowballing exceptions like these threatened to make a mockery of minimums. On June 13, 1948, the Cardinals hosted the Giants in a double-header that was the talk of the offseason. In the first game Clint Hartung got a win for what was effectively a two-out save, later overruled by the league. In the second game Red Munger got a three-inning win after he jammed his finger diving into first base. In July 1949, baseball commissioner Happy Chandler appointed a committee of senior official scorers to solve these winning decision problems. Tom Swope, shortly after being announced as the senior member of that committee, went out and credited a loss to Warren Hacker in a game in which starter Monk Dubiel allowed the go-ahead run (July 6, 1949). Hopes were not high that the group could fix the issue. Nevertheless, in mid-January 1950, Swope, Roscoe McGowen, Dan Daniel, Halsey Hall, and Charles Young agreed on the five-inning minimum and passed along their ruling to Chandler for both leagues. It marked the end of an era of bitterness and bickering and promised a future of fairness and goodwill.

And speaking of Al Spalding, he did, of course, eventually get the win. That came 96 years later when Information Concepts Inc. was given unprecedented access to baseball’s official records for the production of the 1969 Baseball Encyclopedia. Most other pre-1920 pitchers had to wait until the seventh edition of Total Baseball, in 2001, to have proper won-loss records shown. Remarkably, Chadwick himself never retroactively figured won-lost records and never presented a pitcher’s career won-lost total. It seems that to Chadwick what a pitcher did in consecutive seasons was irrelevant given the overall changes in teams and leagues. Charles Radbourn likely died without knowing he won sixty—or close to sixty—games in one season.

Career totals begin with Cy Young, whose win milestones from 300 to 400 to 500 in the first decade of the twentieth century proved irresistible for newspapers who guessed as to his actual lifetime won-lost record. George L. Moreland was a Columbus, Ohio railroad baggage master who became a minor league investor, umpire, baseball reporter, and major league scout in the 1890s. Moreland broke both his ankles early in 1898 and reportedly reviewed all of baseball history while convalescing at Pittsburgh’s eastern district White Ash post office. In 1905 Moreland’s stats began appearing in newspapers. By June 1910, his weekly averages appeared nationally—always “by George L. Moreland” who had made himself a brand. He opened his own sports bureau and published Moreland’s Baseball Records and Percentage Book in 1909.

Moreland was the first to provide lifetime totals for pitchers in press releases that went national, but his works seem to have been stabs in the dark after Henry Chadwick passed in 1908. In 1911 he credited Cy Young with a 504–317 lifetime mark. In 1914, in his magnum opus encyclopedia, Balldom, he presented Young with a 508–311 record. Moreland, Fred Lieb, Ernest Lanigan, and Al Munro Elias all did their own research in secret and nearly every career pitching line published failed to match any other. During this era researchers maintained strict secrecy about their stats lest someone else double-check their totals for accuracy and claim their work.

Moreland had serious stomach trouble during WWI. He lost 100 pounds and ownership of his sports bureau. When he was sick, John Heydler rose to the NL presidency and reportedly asked Al Munro Elias instead for the lifetime hits of Tris Speaker and Cap Anson. Elias pulled an all-nighter counting, presenting Heydler with the totals the next morning. Impressed, Heydler made the very private Elias the NL’s official statistician over Moreland. Secrecy came to rule and even 20 years later, when Lefty Grove won his 300th game, no one knew the won-lost records of the 300-win club. Grove didn’t take any chances. He pitched a complete game.

FRANK VACCARO is a longtime SABR member and Teamsters Local 812 shop steward for Pepsi-Cola (KBI) in Northern Queens, NY. He lives in Long Island City with his wife Maria and their cat Furgood.

Sources

All information on game decisions, scores, and dates, sourced from Retrosheet. Accessed July 2012.

Baltimore Sun, April 27, 1894.

Boston Journal, September 30, 1916, 9. Chicago Tribune, August 1, 1923; July 24, 1940, sec 2, 1.

Frank Williams essay in The National Pastime, 1982, 50.

Joe Wayman essay in the Baseball Research Journal , 1995, 25.

George Moreland, Balldom, 1914, 283.

Los Angeles Gazette, April 2, 1916.

Macon Telegraph, August 24, 1887, 1.

New York Clipper, November 4, 1876, 253.

The New York Times, June 16, 1907; September 28, 1936; October 4, 1937; July 26, 1941, 10; September 2, 1948.

SABR-L electronic bulletin board: post #079724, February 27, 2010; post #084889, January 15, 2012.

Spalding’s Official Base Ball Guide, 1890, pages 32, 53; 1900, 61.

Sporting Life, July 11, 1888, 4; November 14, 1896, 2; July 2, 1898, 5; November 4, 1899, 5; 21 March 21, 1903, 7; February 22, 1913, 14; September 19, 1914, 14.

The Sporting News, July 7, 1888, 6; August 4, 1888, 6; July 17, 1930, 5; May 21, 1931, 7; January 5, 1939, 5; August 10, 1939, 2; May 11, 1944, 16; June 7, 1945, 10; May 21, 1947, 12; July 23, 1947, 36; September 3, 1947, 12; May 19, 1948, 15; July 29, 1949, 6.

Washington Post, August 27, 1912; July 19, 1949; April 19, 1950.

Washington Times, December 3, 1919.

Wheeling Register, March 24, 1895, 7.