SABR Official Scoring Committee: June 2019 newsletter

“You Called That a What . . . ?”

The Newsletter of the Official Scoring Committee

Society for American Baseball Research (SABR)

June 2019, Volume 4, Number 2

Editor:

Stew Thornley

- From the Chair

- Conundrum of the Month (or Quarter or Whatever)

- What’s a Cincinnati Base Hit?

- Profile: Allan Spear

- Bloops and Bobbles

- Conundrum Answer

- Honchos

From the Chair

Bill Zavestoski, official scorer for the San Diego Padres, will be the special guest at our annual committee meeting at the SABR 49 convention in San Diego on Thursday, June 27 from 7:30 to 8:30 a.m. in the Seaport A/B Ballroom of the Manchester Grand Hyatt. Bill has been calling hits and errors from the hot seat for 36 years and will have great stories and observations.

Time permitting, we will also look at videos of plays, let members vote on hit or error, and discuss them.

Time permitting, we will also look at videos of plays, let members vote on hit or error, and discuss them.

In other news, has anyone seen the new book by Christopher J. Phillips, Scouting and Scoring: How We Know What We Know about Baseball? It is a fascinating history of official scoring and scouting, and I recommend it to anyone who has an interest in either. Here is an excerpt from the book, a chapter on official scoring.

Dennis Hetrick, an official scorer for Washington National games, co-hosts the Ordinary Effort Podcast, about official scoring in baseball. Check it out and email Dennis and co-host Jason Lee questions about official scoring at ordinaryeffortpodcast@gmail.com. The Ordinary Effort Podcast is also on Facebook and Twitter.

As usual, keep an eye on our Committee Files page, as the information in there continues to grow,

This issue of “You Called That a What . . . ?” doesn’t have a guest column, but such columns are always welcome as are interviews and profiles of official scorers. If you’re interested in doing either or both, contact me: Stew Thornley.

Conundrum of the Month (or Quarter or Whatever)

Situation: Runner on first and a 2-2 count on the batter, who looks at a pitch that is low, tosses his bat, takes off his body armor, and starts trotting to first. The runner on first starts to go to second as the catcher throws the ball back to the pitcher, who starts to rub it up. Finally, the players realize the batter has not walked, and the first baseman yells at the pitcher to throw him the ball, which he does. The runner starts back toward first base and is tagged out.

How is this scored?

What’s a Cincinnati Base Hit?

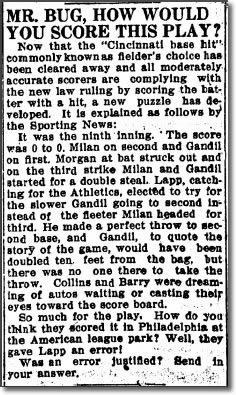

Jim Wohlenhaus sent this clipping from the Ottumwa, Iowa, Courier of May 13, 1913 (page 6):

Jim notes that this referred to a Washington-Philadelphia game, possibly April 30, 1913, but what is a Cincinnati base hit?

The term is used and explained in this biographical sketch of Billy Weart by Charlie Weatherby: “Sportswriters were also involved in scorekeeping in the early 1900s. In May 1913, Weart was instrumental in convincing the writers organization to change the rule that credited batters with hits on fielder’s choice plays, commonly known as the ‘Cincinnati base hit.’”

Chris Phillips elaborates in Scouting and Scoring: How We Know What We Know about Baseball:

As they became increasingly used as official scorers, reporters themselves sought to organize a professional association to manage access to their ranks. Reporters had tried previously to standardize baseball scoring and reporting by forming the Baseball Reporters’ Association in 1887, but this and subsequent attempts had floundered.” [Source: Ernest J. Lanigan, “Origin of Statistics” in Baseball Register, pp. 33-36 (St. Louis: Sporting News, 1942).]

Baseball writers tried again after the turn of the century, the impetus being the 1908 World Series when out-of-town writers were placed in the back row of the grandstand in Chicago and “compelled to climb a ladder” to reach the roof of the first base pavilion for the games in Detroit. By the final game on October 14, a group of prominent writers had met in Detroit, and “a temporary working organization was effected.”

The first formal meeting of the Base Ball Writers’ Association of America (BBWAA) was held in New York in December 1908 with Joseph Jackson of Detroit elected president. The first concern was to “secure creature comfort”by reducing the number of people in the press box and improving access to them for qualified writers.

The BBWAA was also interested in facilitating scoring reforms.

In 1913 the BBWAA scoring committee advocated for, among other things, a clearer stance on earned runs. It also adopted the “Cincinnati hit,”` replacing the fielder’s choice ruling in situations in which both the runner on base and the batter-runner were ruled safe. Called this because its main advocate was Jack Ryder, a Cincinnati reporter and official scorer, the new rule was reversed by the BBWAA after a single season.

Lyle Spatz, in the June 2003 newsletter of the SABR Baseball Records Committee, wrote about the Cincinnati base hit after receiving a stack of clippings on the subject from Tom Voll that revealed that it was a one-year scoring practice used in 1913.

When a batter hit to the infield with a man on base, and the infielder chose to try for a force play or fielder’s choice and was unsuccessful, the batter was given a hit. There is no way of knowing how many batters benefitted by this rule, or to what extent. However, we do know of one example of a “Cincinnati Base Hit.” It occurred in the final game of the 1913 World Series. In the top of the third inning, Philadelphia had Rube Oldring on second base and Eddie Murphy on third, when Frank Baker rolled a grounder to first. Giants first baseman Fred Merkle picked up the ball and went to tag Baker. But Baker stopped running and Merkle got confused. He then threw to the plate, but it was too late to get Murphy and everyone was safe. Baker was given a hit.

Following the season, the Baseball Writers Association voted 35-26 to abolish “Cincinnati Base Hits.”

This topic had also been broached by David McDonald on the SABR-L listserv December 13, 2004, in which he recounted a Cincinnati base hit that resulted in a bizarre scoring sequence:

I came across a pretty interesting triple play in Norman Macht’s “The Cincinnati Base Hit” in SABR’s Road Trips. In it, Macht describes a May 16, 1913, game between Cleveland and Philadelphia, in which Ivy Olson singled into a triple play. (For 1913 only, Olson’s ground ball to short to start the play would be scored not a fielder’s choice, but a single—a “Cincinnati single.”)

The play went something like this: With Don Johnston on third and Ray Chapman on second, Olson hit a grounder to Barry at short. Barry bobbled the ball, then threw home to catcher Thomas, who threw to Baker at third, who threw to pitcher Houck on the third base line. Houck threw to SS Barry, now covering third, Barry tagging Johnston. Barry then threw to Collins at second, who tagged Olson. Meanwhile, runner Chapman had rounded third. Collins threw to 3B Baker, who was covering home. Chapman retreated. Baker threw to LF Oldring, who had moved in to cover third. Oldring tagged Chapman.

So I guess the scoring goes 6-2-5-1-6, 6-4, 4-5-7—one single, one bobble, eight assists, three outs on one play.

Profile: Allan Spear

Allan Spear has been an official scorer in Chicago for the White Sox and Cubs. On May 2, 2002, he shadowed Don Friske, the official scorer for the Seattle-Chicago game. Mike Cameron hit four home runs for Seattle in that game.

How did you get into official scoring?

I had been covering games for STATS for 10 years, when one day out of the blue the Cubs PR Director said “Allan, you want to be an Official Scorer?” I thought about it for 1/8th of a second, and started training the next week,

What interesting situations have you encountered while scoring?

The most interesting was a couple of years ago when the Cubs had Anthony Rizzo playing 1B and Javier Baez playing 2B. The Pirates had a runner on 1st and were in an obvious sac bunt situation. Rizzo traded his first baseman’s mitt for a regular glove, and set up about 40 feet from the batter (waiting for the bunt), while Baez went over to the first base bag and held the runner on. That led to a big discussion of what position each guy was playing — was Baez the first baseman then? And if so, does that mean Rizzo was now the second baseman? I had never seen that before.

The most memorable games were covering Cole Hamels’ no-hitter and the David Bote walk-off pinch grand slam.

What advice do you have for people interested in official scoring?

Knowing the scoring rules is pretty important, but even more important is to be willing to put ego aside and double check the rule book, or check the replay, or ask Elias for their opinion. It is more important to get the call right than to show how everyone how smart and arrogant we are.

Anything else?

If you would have told 12-year-old Allan that he would be spending a good portion of his adult life sitting in the pressbox, getting paid by Major League Baseball to collect statistics, he might have simply exploded with excitement. This is, without a doubt, the most awesome job in the universe.

Bloops and Bobbles

Gene Gomes discovered this gem in the July 20, 1891 Seattle Post-Intelligencer:

(Click image to enlarge.)

Sports Betting

The impact of sports betting will affect, among others, official scorers, who have been briefed on not tipping information. Henry Schulman of the San Francisco Chronicle covers the issue: A Hundred Years after the Black Sox Scandal, MLB Embraces Baseball Betting

Exceptional Efforts

Lea Moss has been exploring the inverse of an unearned run, trying to determine how many runs pitchers are saved by great plays in the field, what she calls “Exceptional Efforts (EE),” the opposite of errors.

Recently she heard Orel Hershiser on a baseball broadcast wonder if he should mark a star on his scoresheet on a fly ball that had been caught. “Obviously he’s a commentator, not an official scorer,” Lea said, “but it did make me think that there must already be at least enough markings on knowledgeable scoresheets throughout the league to be able to a take cursory look at the data for this.”

What Lea is looking for are “defensive plays that were not expected to be made with ordinary effort. Plays that deserve to end up on the defensive highlight reel. Plays where you mark a star next to ‘F8’ on your scoresheet when the center fielder makes an extraordinary catch.

“For the Alpha phase of this research I’m looking to gather and analyze scoresheets from 2018 that contain this unofficial marking. Do you score games? Do you have a consistent chunk of detailed scoresheets from last year?

“Please contact me, I would be very grateful for any participants who can share their scoresheets for this study.”

— Lea Moss, zazubuckeye@GMAIL.COM

Shift Rule in Atlantic League

The Atlantic League (an independent professional league) is experimenting with different rules, including one that requires two infielders on either side of second base. A violation of the shift rule occurred April 25: The Atlantic League Utilizes the No-Shift Rule for the First Time.

James Loney of the Sugar Land Skeeters grounded out to second but was awarded first base when the umpires rules that the Southern Maryland Blue Crabs had violated the no-shift rule. How to score the play? It was decided to charge Blue Crabs second baseman Angelys Nina (the player violating the rule) with an error. Loney was not charged with an at-bat. This is similar to catcher interference, which produces a runner whose run will be unearned if he scores, but the error does not affect the number of outs that there would be without the error.

However, the penalty had been misapplied. Rather than the batter being awarded first base, a ball should have been added to the count. This is similar to a ball being added because a pitcher went to his mouth while on the mound or because the pitcher took too long to throw a pitch.

On a side note, when is the last time a pitcher has been penalized for taking too long to pitch? I was at a Seattle Pilots at Minnesota Twins game September 20, 1969 when Diego Segui of the Pilots took too long to pitch, resulting in a ball being added to the count and also in Seattle manager Joe “S. F.” Schultz being ejected. Can anyone come up with any examples of this happening since then?

Four-base Error

We’ve talked about this kind of play, although I haven’t seen it in the majors. But this clip was posted on the SID Scoring Assistance Facebook page. A game at New Mexico in 2017. Nic Ready of Air Force hit a fly to left. The left fielder is Beau Capanna. It was a four-base error:

Click here to watch video of the play

Conundrum Answer

The runner is caught stealing, 1-3. (It may be recorded as a pickoff-caught stealing by some scoring services although pickoff is not an official statistic.)

This play happened in the top of the sixth inning in a Toronto at Minnesota game April 15, 2019 with Brandon Drury thinking he had walked, prompting Teoscar Hernandez to start for second. Martin Perez, after getting the ball from Mitch Garver, threw to Chris Cron to put out Hernandez.

Link to video of play: Blue Jays 5, Twins 3 (Go to the “Perez Picks off Hernandez“ video.)

Because Hernandez had started for second and because he would have been credited with a stolen base had he reached second safely, he was charged with a caught stealing. Although Garver threw the ball back to Perez, it was not considered part of the play that retired Hernandez, so he did not receive an assist.

Honchos

Stew Thornley—(Chair and Newsletter Editor)

Marlene Vogelsang—(Vice Chair)

Gabriel Schechter—(Vice Chair)

Bill Nowlin—(Vice Chair)

Sarah Johnson—(Vice Chair)

John McMurray—(Vice Chair and Liaison to the Oral History Research Committee)

Art Mugalian—(Assistant to the Traveling Secretary)