SABR Official Scoring Committee: October 2017 newsletter

“You Called That a What . . . ?”

The Newsletter of the Official Scoring Committee

Society for American Baseball Research (SABR)

October 2017, Volume 3, Number 1

Editor:

Stew Thornley

- Howdy

- Conundrum of the Month (or Quarter or Whatever)

- Non-Guest Column

- Q & A with Gary Mueller

- Official Scorers Confab at Winter Meetings

- Conundrum Answer

- Honchos

Howdy

As usual, keep an eye on our Committee Files page, as the information in there continues to grow, including:

- Bill Nowlin did an interview with New York scorer Billy Altman. We’re always looking for more interviews and articles on scorers. Let me know if you’d be interested, and I’ll help put you in touch with some scorers.

- Billy and fellow New York scorers Jordan Sprechman and Howie Karpin were featured in The Hardball Times: Making the Call: Keeping Score in Baseball’s Toughest Market, Part 1. Here is Part 2.

- Stephen Marche had an eye-opening article in the October 2, 2017 The New Yorker: The Error in Baseball and the Moral Dimension to American Life.

In other news … dang, we lost David Vincent. When David was diagnosed with cancer a few years ago, he quit his regular job. He said he wanted to spend his time doing what he enjoyed, and he did. What he enjoyed was official scoring for the Washington Nationals and for minor-league teams in the area. He also enjoyed maintaining the Home Run Log and being a major contributor to one of the best sites ever developed, Retrosheet. Thanks to David, the names of official scorers are now listed for all games going back to 2004.

Dave was a friend of the umpires, too, meeting them as they came through Washington and gathering information on them for Retrosheet. David kept scoring up to a few weeks before his death on July 2, 2017. There were a lot of articles about in, and here is one of my favorites, from Chelsea James of the Washington Post:

R.I.P. David Vincent, the Nationals Scorekeeper Who Brought Out the Joy in Baseball

David was a vice chair of the Official Scoring Committee, which is now adding two more vice chairs, Bill Nowlin and Sarah Johnson.

This issue of “You Called That a What …?” contains a non-guest column (by me) and a question-and-answer with Gary Mueller, an official scorer in St. Louis.

Guest columns are always welcome as are interviews and profiles of official scorers. If you’re interested in doing either or both, contact me: Stew Thornley

Conundrum of the Month (or Quarter or Whatever)

This is more of a curiosity than a conundrum. In the top of the eighth inning of the September 23, 2017, Minnesota at Detroit game, Zack Granite pinch-ran for Joe Mauer. The Twins batted around, and Granite came to bat. He hit his first-major league home run. In the bottom of the inning, Granite went to left field. Was his home run credited to him as a pinch-hitter or as a left fielder?

Non-Guest Column

By Stew Thornley

Always wear clean underwear; you never know when you’re going to score.

Keeping score of baseball games is something I’ve been doing for as long as I’ve been watching baseball. Like others, I began with a rudimentary system and enhanced it to the point that I can go back through my scoresheet and reconstruct what happened in the game in detail. One of the best pointers I picked up along the way was from the “How to Score” section in an early 1960s Twins program on how to indicate the progress of a baserunner by using the fielding-position number of the batter who advances the runner. Other refinements included the addition of balls and strikes and symbols to indicate whether a hit was a line drive or ground ball.

One fan used the “How to Score” book published by The Sporting News to write a snarky letter that was pubished in the April 19, 1969 Voice of the Fan.

In addition to keeping score of games I attended when I was young, I enjoyed going through The Sporting News Official Baseball Guide that my dad got each year. These contained complete play-by-play of the All-Star Game and World Series. I’d use these accounts to practice my scorekeeping, entering the games and individual plays into my scorebook. Then I’d go back and reconstruct the game from my scoresheet to make sure it reflected all the details present in the written play-by-play account.

I rarely kept score in a program purchased at the stadium. Instead, I bought my own scorebooks, preferring the Wilson brand, until early in the 1990s when I started designing my own. Along the way, I discovered I had a pretty good knack for scorekeeping as I could do a lot of things while still having no trouble keeping a pitch-by-pitch tally (part of my normal multi-tasking personality, I guess).

Although I’d done some official scoring, for the state community college tournament in the 1980s and for Minnesota Loons (an independent-league team) games in the 1990s, I thought this was another of those relatively useless skills that I had an affinity for (like being able to belch the rhythm to “Shave and a haircut” while keeping enough in reserve to finish it off with “two bits”). However, in 1998, SABR member Kevin Hennessy asked if I wanted to do “cybercasting” of Twins games for Total Sports (which was taken over in 2001 by mlb.com), transmitting pitch-by-pitch data to a web site.

A different scoring style was used, one that would allow for easy data entry rather than a graphically based system (drawing a diagram as a runner progressed on the bases). A code for a line single to right that moved a runner from first to third is S9/L.1-3. This kind of entry allows a computer program to automatically spit out a play-by-play description: “Guerrero hit a line-drive single to right, Vidro to third.”

As I worked these games, I did what was required for the code entry into the computer, but I stuck to my graphical style on paper.

I’ve discovered that I can “read” a game better off a graphical scoresheet than one that uses the data-entry style. If I wanted to write a game story, I could reconstruct what had happened in the game more easily by looking at a graphical style than I could with a data-entry style or even with a written play-by-play account (the type found in The Sporting News Official Baseball Guides).

In fact, when I was doing a project to write a profile on each of the Game Sevens in the World Series, I started by going through the written descriptions of the games and scoring them on paper, which allowed me to quickly see the flow of the game and the significant plays.

A completed scoresheet becomes a work of art, much like a musical score. In this case, it’s not the person entering the hieroglyphics who is the artist; rather it is the players on the field, creating the events that are then recorded. At the end of the game, the scorer has a unique piece of art, as individual as a snowflake or a fingerprint, no two games ever being the same. (Jim Gates, the library director at the National Baseball Hall of Fame, calls scoresheets “the first draft of baseball history.”)

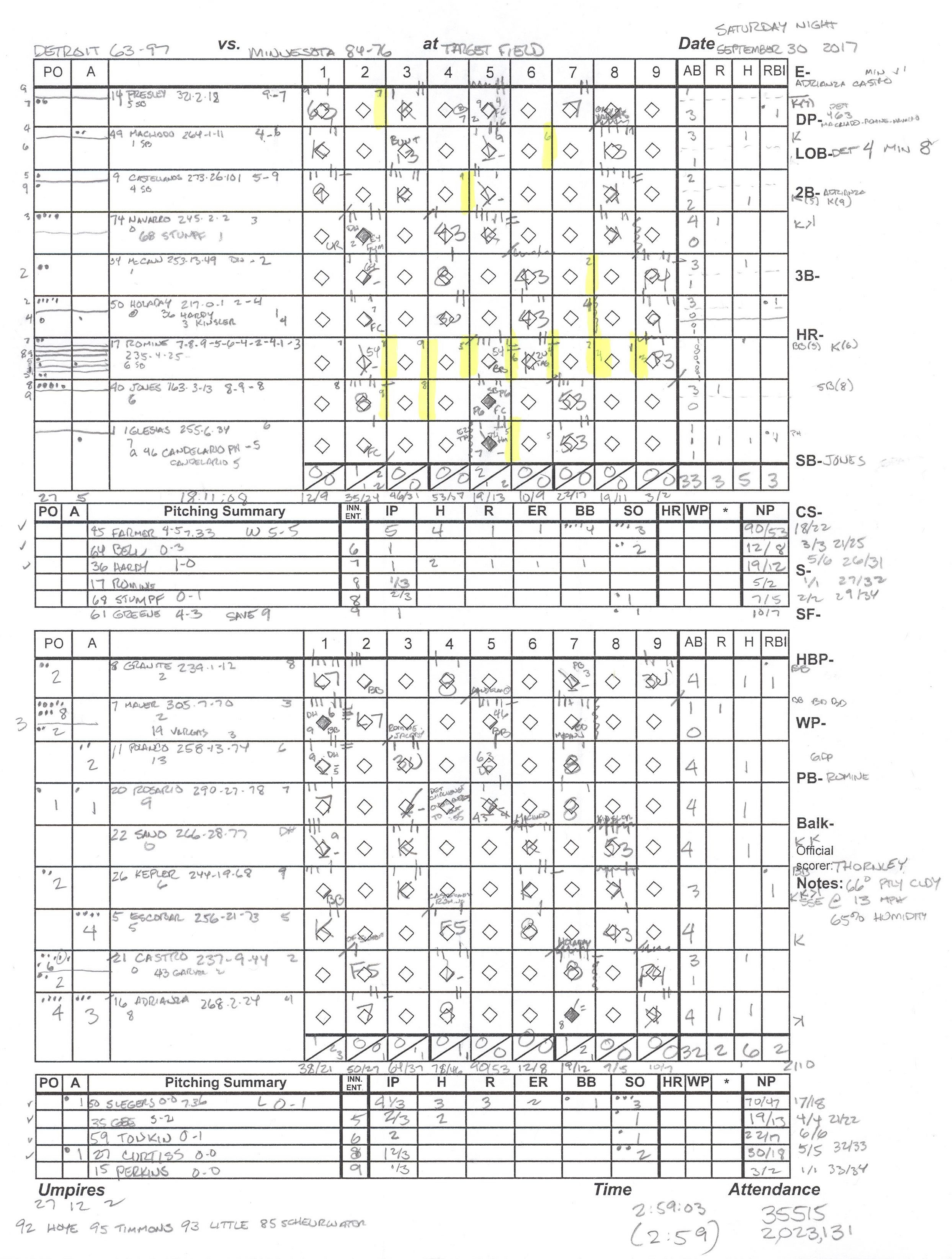

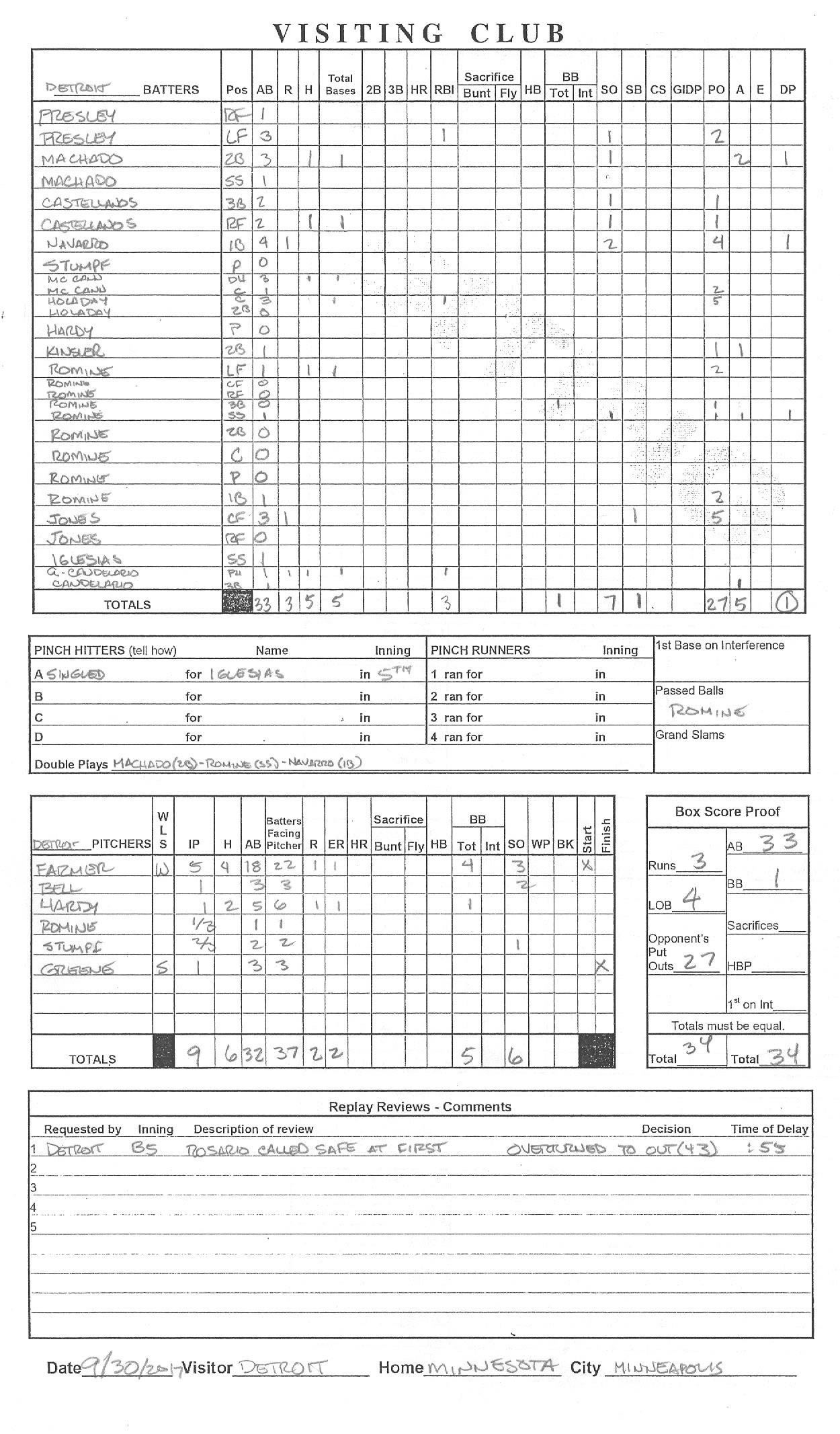

Below is my scoresheet from the September 30, 2017 Detroit at Minnesota game in which Andrew Romine played all nine positions:

Click on the image to enlarge; click a second time to enlarge more.

The official scorer has to enter fielding and offensive statistics for each player, by position. It’s usually not a problem if a player changes positions—once. I use a yellow highlighter on a player’s batting line to segment each plate appearance by the fielding position he has at the time, and I draw a line in his boxes for put outs and assists to keep those separate by position.

After the game I carefully separated the put outs and assists as well as all offensive numbers into separate lines onto the box score I compile and send to Elias Sports Bureau. It didn’t take much longer than it normally does.

|

|

Click on the images to enlarge; click on them a second time to enlarge more.

Favorite scorekeeping story: At the first Puerto Rican League game I attended, in December 1996, I relied on the scoreboard for names of the players and umpires. (There were no scoresheets and even the stat sheets in the press box contained no uniform numbers.) In the eighth inning, Santurce changed pitchers, and I watched the scoreboard carefully for the name of the new pitcher. As “Nuevo Lanzador” flashed onto the screen, I wrote it down on my scoresheet. A couple minutes later, the person in front of me turned and said, “You know, Houston is grooming Billy Wagner as its closer.” I thought, “This is Wagner? I thought it was Lanzador.” I scratched out what I had written and wrote in Wagner’s name. When San Juan changed pitchers in the top of the ninth, and I again saw the same message flashed on the scoreboard, it finally hit me that “Nuevo Lanzador” means “New Pitcher.” Meanwhile, I still have a scoresheet with an entry reading “Lanzador, Nuevo Wagner, Billy.”

Q & A with Gary Mueller

How did you get into official scoring?

My first scorekeeping job came when I was 7 years old. My father was part-owner of a minor league team. My job was to sit on a little catwalk atop the right field fence and hang metal numbers from a nail each half-inning, showing how many runs were scored.

When I was 12, my uncle, a former major league pitcher, was manager of a semipro team in a local county league. He appointed me scorekeeper for the team. When one of the players told me a walk counted as a hit for purposes of computing a batting average, Uncle Les told him, “Gary knows more about scoring and baseball rules than anyone on this team.”

After that, I always kept a scorebook for any game I attended, and eventually, in 2000 became one of the official scorers at Busch Stadium in St. Louis.

What interesting situations have you encountered while scoring?

I can think of numerous interesting situations:

(1) Early in the 2000 season, in one of my first games as an MLB official scorer, Cardinals second baseman Fernando Vina called the pressbox during the game and said he wanted to talk to me after the game. I had ruled an error on a ball Vina had hit to San Diego second baseman Bret Boone.

When I got to the clubhouse, Vina told me that when he reached base on that play, Boone told him it should have been ruled a hit. Vina wanted me to go talk to Boone. So I walked down the hall to the San Diego dressing room and told him what Vina had said. “I was just playing with him,” Boone told me. “That was an error all the way.” As I walked away, Boone called out to me and asked, “What are you going to tell Vina?” I replied that I was going to tell him that Boone was just playing with him.

“Naw, don’t do that. There were earned runs involved, too, weren’t there? Tell him I’ll take an error to save my pitcher.”

I kept it an error and Padres pitcher Brian Boehringer was saved 5 earned runs! Ironically, Boehringer is now a balls-outs-strikes supervisor for MLB and often sits alongside me when I’m scoring. He got a good laugh when I told him the Boone-Vina story.

(2) In 2001, when Mark McGwire was in a season-long slump (he finished with a .187 average that year), he asked me to take another look at a replay of a ball he hit that I had ruled E3. McGwire thought he should be credited with a hit because the ball had taken a funny hop. So I went to the video room, looked at the replay and didn’t see any funny hop. I went back to McGwire and told him I was keeping it as an E3. He shrugged and said, “Oh, well, that’s why you get paid the big bucks.”

(3) In a game in 2005, Yadier Molina was called out for passing Abraham Nunez on a play when Molina hit a ball to the wall in right that Nunez, the runner on first, thought had been caught, so Nunez headed back toward first. Molina, who had rounded first, was completely stationary, waving frantically for Nunez to go to second, when it actually was Nunez, in retreat, who passed Molina. But, of course, it was Molina who was called out. Then, Nunez headed toward second and was thrown out by the right fielder. On the press box PA, I announced a single and RBI for Molina (the runner on second when the crazy play began had scored easily), and the appropriate scoring details on the bizarre double play.

But then I got to thinking about it: could I give Molina a single when the runner on first never made it safely to second base? I walked down to the other end of the press box to discuss it with Hall of Famer (Spink Award winner) Rick Hummel to see what he thought. Hummel was sitting next to legendary basketball coach Bob Knight, who was paying a visit to Hummel and Post-Dispatch columnist Bernie Miklasz. When I asked Hummel whether Molina could be credited with a hit, Knight immediately replied, “Yea, they just announced it.” As Hummel and Miklasz burst into laughter, I told Knight that I was the one who had made the announcement.

I then called Elias and Seymour Siwoff himself answered the phone(!). He confirmed that Molina indeed could be credited with a hit, because once he passed Nunez, there was no longer a force at second, and Nunez could have safely returned to first base. I’m still not sure that’s really the correct call, but if Bob Knight and Seymour Siwoff agree, who am I to disagree?

(4) On July 21, 2012 (I remember the exact date because that’s the anniversary of the 24-inning game in which my uncle pitched the first 19 and 2/3 innings), Starlin Castro, playing shortstop for the Cubs, made a nice stop up the middle, spun, and threw wild to first base. I called it an E6 throwing error. That weekend when we had a family barbecue, my uncle told me he was watching the game and the announcers called me out by name and thought it should have been scored a hit. I told him the Cardinals had submitted the play for review and explained the whole review process. His comment: “If they don’t have a former pitcher making those decisions, they’ll always change errors to hits. That was an error.” Sure enough, the call was changed. When I told my uncle that it had been changed to a hit, he said “Skeeter Webb makes that play. Without the pirouette.”

(5) 2013 World Series, the famous Will Middlebrooks/Allen Craig obstruction call that ended game three. When the play occurred, there was a great deal of confusion in the press box, but thanks to the clear, concise gestures by third base umpire Jim Joyce and home plate umpire Dana DeMuth, I knew exactly what had happened and immediately announced the obstruction ruling over the press box PA.

(6) Earlier this year, in his major league debut, the Cubs’ Ian Happ hit a ground ball that Cardinals first baseman Matt Carpenter deflected into right field. I called it an E3 fielding error. The ball was rolled into the Chicago dugout as a souvenir for what the Cubs thought should be Happ’s first major league hit. In no uncertain terms, I was told that the Cubs were “livid” that I had called it an error and if I didn’t change it, the play would be sent in for review. I looked at the replay several times and kept it as an error. On Happ’s next at bat he hit a home run, making his first official major league hit a home run! To my knowledge, the Cubs never submitted the E3 for review.

What advice do you have for people interested in official scoring?

Two things: know the rule book and keep score of as many games as you can. You have to know all the rules, not just the scoring rules, so you can properly account for everything that happens in a game. Keep score of every game you can, at all levels. Imprint in your mind what plays can be expected to be made at all levels, from little league to the majors.

What sorts have things have you learned since you began official scoring?

I’ve learned being the official scorer isn’t as easy as it looks. Everyone, from the players to front office personnel to reporters, takes scoring decisions very seriously. Unlike an umpire’s call, a scorer’s decision doesn’t have a direct impact on the outcome of the game, but that doesn’t mean your call isn’t going to be scrutinized and possibly criticized loudly. You have to develop a thick skin.

What is your background, including other interesting things about you (family/job/hobbies, etc.)?

Much of this is spelled out in answer to the first question. I’m a graduate of the University of Missouri School of Journalism and for many years was a sportswriter at the St. Louis Post-Dispatch.

I enjoy travel. Foreign highlights have been trips to Australia, Cuba and Easter Island. In the U.S, I have been to the four extreme points of the contiguous states. My wife (Bonnie) and I have driven the entire perimeter of the U.S., as close to the border as we could get, and have visited and photographed 49 state Capitols. All except Idaho.

Why have you never been in Idaho?

Ever since I was a little kid, I’ve been interested in maps and geography. When I was 5 or 6, I was given a jigsaw puzzle of the U.S. with each state a separate piece. Whenever we went on a family vacation, or visited another state, the first thing I did when I got home was put that piece in place in the puzzle. Over the years, as it filled up, probably around 35 or 40 states, I realized I never wanted that puzzle to be completely filled, so I decided that when I got to 49 states, I would NEVER step foot in whatever state was #50. It just happened that #50 was Idaho. I’ve had my toes on the state line three different times, but I’ve never crossed into Idaho.

Where do you plan to have your ashes scattered?

I have requested to be cremated and have my ashes scattered in Idaho.

Official Scorers Confab at Winter Meetings

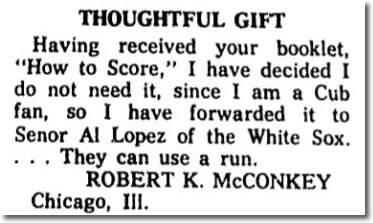

Sarah Johnson recently spoke to the Halsey Hall Chapter of SABR on baseball’s winter meeting that was held in Minneapolis 69 (nice) years ago. She learned that the event included a meeting of minor-league official scorers, as described in Halsey Hall’s column in the December 10, 1948 Minneapolis Tribune.

Click on the image to enlarge; click a second time to enlarge more.

Fun Fact: The committee decided that a starting pitcher shouldn’t remain eligible for a win if he’s ejected before completing five innings. That makes sense. However, did you know that did you know that the scoring rules (9.23) include guidelines for cumulative performance records? 9.23(c) reads, “CONSECUTIVE-GAME PLAYING STREAK. A consecutive-game playing streak shall be extended if a player plays one half-inning on defense or if the player completes a time at bat by reaching base or being put out. A pinch-running appearance only shall not extend the streak. If a player is ejected from a game by an umpire before such player can comply with the requirements of this Rule 9.23(c), such player’s streak shall continue.”

Granite had no position or designation when he hit the home run. He hit it as a “nothing.”

The good folks who know how to mine information from Retrosheet and the baseball-reference.com Play Index, including Tom Ruane and Wayne McElreavy, came up with a partial list of players who have hit a home run as a nothing:

Pat McNulty, 4-14-1925

Al Zarilla, 6-10-1952

Johnny Temple, 6-6-1953

Wayne Belardi, 7-18-1953 (grand slam)

Fred Marsh, 7-29-1953

Frank House, 4-21-1958 (grand slam)

Gene Stephens, 7-13-1959 (grand slam)

Von Joshua, 7-22-1970

Dave Kingman, 7-1-1973

Cliff Johnson, 5-31-1975

Bill Robinson, 8-14-1982 (grand slam)

Jeff Stone, 7-6-1986

Alvaro Espinoza, 4-8-1993

John Cangelosi, 6-25-1995

Willie McGee, 5-9-1996 (grand slam to give him 5 RBIs in the inning)

Ryan Christenson, 9-30-2000

Steve Clevenger, 9-11-2015 (grand slam, the second grand slam of the inning)

One that doesn’t make this list is a home run by Darren Lewis for Boston on April 18, 2001. Lewis pinch-ran for designated-hitter Manny Ramirez and came up later in the inning, hitting a home run. However, when Lewis came up he became the designated hitter.

In case you were wondering, John Cangelosi holds the record by coming to bat as a nothing six times in his career.

Stew Thornley—(Chair and Newsletter Editor)

Marlene Vogelsang—(Vice Chair)

Gabriel Schechter—(Vice Chair)

Bill Nowlin—(Vice Chair)

Sarah Johnson—(Vice Chair)

John McMurray—(Vice Chair and Liaison to the Oral History Research Committee)

Art Mugalian—(Assistant to the Traveling Secretary)