The ‘Strike’ Against Jackie Robinson: Truth or Myth?

This article was written by Warren Corbett

This article was published in Spring 2017 Baseball Research Journal

This article was honored as a 2018 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award winner.

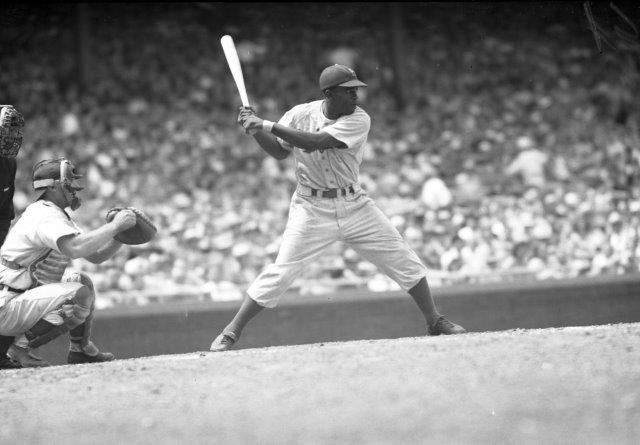

A National League players’ strike, instigated by some of the St. Louis Cardinals, against the presence in the league of Jackie Robinson, Negro first baseman, has been averted temporarily and perhaps permanently quashed.

That’s the lede of Stanley Woodward’s story in the New York Herald Tribune on May 9, 1947, four weeks after Robinson’s debut.1 The strike story has become part of the Robinson canon, a vivid illustration of the racist resistance he faced. It won the E.P. Dutton Award for best sports reporting of the year, and the writer Roger Kahn called it “the sports scoop of the century.” The Cardinals’ Enos Slaughter said of Woodward, “That son of a bitch kept me out of the Hall of Fame for twenty years.”2

Yet hard evidence of a strike plot is lacking. Woodward’s story was flawed, but his disciples — most prominently Kahn, author of The Boys of Summer — have defended his reporting for seven decades. Critics — led by St. Louis sportswriter Bob Broeg, who called the Tribune story “a barnyard vulgarism” — believe the “plot” was the product of some empty rants by players, plus a paranoid owner and a headline-seeking sportswriter.3 Jules Tygiel, in his landmark book Baseball’s Great Experiment, concluded that it was “an extremely elusive topic.”4 This review will explore the maze of conflicting evidence and try to arrive at the truth.

WOODWARD’S SCOOP

Woodward’s indictment went like this: Some of the Cardinals had schemed to organize other teams to refuse to take the field against Robinson in the hope of driving him out of the league and preserving major-league baseball for White men only. But National League president Ford Frick confronted the ringleaders and forced them to back down.

Woodward wrote, “Frick addressed the players, in effect, as follows: ‘If you do this, you will be suspended from the league. You will find that the friends you think you have in the press box will not support you, that you will be outcasts. I do not care if half the league strikes. Those who do will encounter swift retribution. And will be suspended, and I don’t care if it wrecks the National League for five years. This is the United States of America, and one citizen has as much right to play as another.’”

Dodgers broadcaster Red Barber called the speech Frick’s “finest hour.”5 Other writers have quoted it ever since.

It never happened. Frick never spoke to any Cardinals players. Woodward acknowledged that the day after he broke his big story, and Frick said so, too.6

Woodward cited no sources, not even anonymous ones. He wrote, “It is understood…”, “it is believed…”, and “we can report…” He named no conspirators, probably because the paper’s lawyers wouldn’t let him. Robinson is the only player mentioned by name. The story resembled the “blind items” usually confined to gossip columns: Which married Broadway chanteuse was spotted canoodling with her co-star at Sardi’s? That may explain why the explosive report appeared in the sports pages, not on the front page, although Woodward blamed a racist editor.

DISSECTING THE SCOOP

As best events can be reconstructed so long afterward, here’s how it happened, based on published accounts: The Cardinals owner, Sam Breadon, picked up rumors that some of his players were talking about striking in protest against Robinson. Breadon’s source may have been Dr. Robert Hyland, the team physician. At the least, Hyland was the man responsible for letting the story out.

As best events can be reconstructed so long afterward, here’s how it happened, based on published accounts: The Cardinals owner, Sam Breadon, picked up rumors that some of his players were talking about striking in protest against Robinson. Breadon’s source may have been Dr. Robert Hyland, the team physician. At the least, Hyland was the man responsible for letting the story out.

Sam Breadon was born poor and started his business career peddling popcorn at the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair. He got rich selling cars — Pierce-Arrows — but never escaped his origins; he was tight with a dollar and always worried about where his next one was coming from. In his anxious mind, even the whisper of a strike sounded like the roar of a crisis.

According to both Frick and Breadon, the Cardinals owner had rushed to New York to report the rumors to the NL president. Frick told him that any strikers would be punished and the league would stand behind Robinson. Breadon met with the team leaders, shortstop Marty Marion and captain and center fielder Terry Moore, who assured him that the strike talk was only talk, a few players venting. In his memoir, Frick said Breadon reported back that it was “a tempest in a teapot.”7

Exactly when Breadon talked to Frick has never been established. Woodward said the strike threat was the reason Breadon went to New York just before the Cardinals played in Brooklyn on May 6, but Frick said they had spoken two or three weeks earlier.8 Breadon went to New York in May because his club had lost nine straight games and he was in a panic, not unusual for him. The day before Woodward’s story was published, the Cardinals finished winning two out of three from the Dodgers without incident.

The rumors had begun to leak out a few days before that series when the Yankees went to St. Louis to play the Browns. Dr. Hyland had dinner with Rud Rennie, who covered the Yankees for the Herald Tribune, and confided that Breadon feared a possible strike that could destroy his ball club.

Rennie knew a hot story when he heard one, but he couldn’t write it without burning his friend Hyland. He passed the information to his boss, sports editor Woodward.

Stanley Woodward was a titan of the New York sportswriting fraternity. A massive former football tackle at Amherst College, Woodward liked to be called “Coach.” He was too old and too nearsighted for military service in World War II, so he volunteered as a war correspondent and landed in the Nazi-occupied Netherlands aboard a glider. Woodward was tough and blunt, and was fired in 1948 after he told the Tribune’s owner that her society golf tournament wasn’t worth covering.

How the alleged strike threat morphed from dinner-table chat to Herald Tribune headline is transparent. Although Woodward didn’t identify his source, he later told Roger Kahn that he had talked to Frick.9 The NL president, a former New York sportswriter and Babe Ruth’s ghostwriter, knew how to plant a story without leaving fingerprints. And he was the hero of Woodward’s account. But Woodward misunderstood what Frick told him and mistakenly reported that Frick had spoken to the players.

After writing that the strike was “instigated by some of the St. Louis Cardinals,” Woodward switched targets two paragraphs later and said it had been “instigated by a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers, who has since recanted.” That is an unmistakable reference to Dixie Walker. The star right fielder, who came from Alabama, had circulated a petition against Robinson among his teammates during spring training and had written a letter to Dodgers president Branch Rickey asking to be traded rather than play with a Black man. Walker was a Brooklyn favorite known as “The People’s Choice,” but when he appeared at Ebbets Field for the first time in 1947, Robinson’s partisans booed him.10

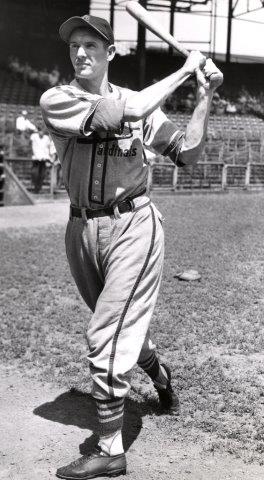

While Woodward didn’t name names, he laid blame on White southerners — “boys from the Hookworm Belt,” as he contemptuously called them. The Cardinals roster could have filled out a platoon in the Confederate Army. Terry Moore, born in Alabama, grew up in Memphis and St. Louis. Marty Marion’s South Carolina pedigree was said to trace back to the Revolutionary War “Swamp Fox,” Francis Marion. Manager Eddie Dyer and pitcher Howie Pollet came from Louisiana, Enos Slaughter from North Carolina, Harry Walker from Alabama. And Harry was Dixie Walker’s younger brother.

THE BACKLASH

Woodward’s blockbuster sent other reporters scurrying to catch up. Of course, all the Cardinals denied it. “That’s an out and out lie,” Breadon shouted to St. Louis writer Sid Keener. “It’s New York again trying to stir trouble in our organization.”11

“Absurd,” manager Dyer said. “Nobody on the Cardinals ever thought of such a thing.” Then he added a key point: “I’d have known about it.”12 Dyer had managed many of the Cardinals coming up through the farm system. Several worked for him in his Houston insurance business, and his wife, Geraldine, was the godmother of their children. Someone would have tipped him off if a strike was percolating in his clubhouse.

Frick, however, confirmed that Breadon had come to him with the rumors. “I didn’t have to talk to the players myself,” Frick said. “Breadon did the talking. From what he told me afterward, the trouble was smoothed over.”13

The Cardinals players did not deny that there was bitter opposition to Robinson. They did deny that it amounted to anything more than noise. Terry Moore dismissed it as “some high-sounding strike talk that meant nothing.”14 Stan Musial said, “I thought the racial talk was just hot air.”15

Years later, Frick told writer Jerome Holtzman, “I thought very little of it until the story broke. The way Woodward wrote it, you would have thought all the St. Louis players were against Robinson.”16

As exaggerated as it was, the story reset the conversation about Robinson after he had played just 15 games. Most of the White press, while routinely referring to him as the “Negro first baseman,” had been tiptoeing around the racial angle. Sportswriters wanted to write about baseball, not social change.

Phillies manager Ben Chapman had already been widely condemned for his vicious bench jockeying of Robinson, the ugliest public incident of the year. (Chapman and Dixie Walker were close friends and had been roommates with the Yankees.) Now big-name sports columnists rallied to Robinson’s side, repeating Woodward’s accusations and defending Robinson’s right to play. Jimmy Cannon of the New York Post wrote, “There is a great lynch mob among us and they go unhooded and work without rope.”17 The Sporting News, a longtime apologist for segregated baseball, editorialized that “the presence of a Negro player in the majors is an accomplished fact, which no amount of ill-advised strike talk can affect.”18

The African American sportswriter Sam Lacy thought the tide of support from Frick and the White press was a turning point signaling acceptance not just of Robinson, but of integration. “[A]t long last, it looks as though we have the wind at our backs,” Lacy wrote.19

THE FALLOUT

The story quickly faded from the newspapers, but it has reverberated down through the decades as the Robinson saga was told and retold. Generations of writers have recycled Woodward’s version, quoting the speech Frick never delivered. The sportswriter Jerry Izenberg, another Woodward acolyte, said, “All Stanley did was change history.”20 That is not so. Even if there was a scheme to strike, it was dead by the time Woodward made it public.

Over the past 70 years, just a few players have recalled conversations or activities that seemed connected to a strike plot. Those memories were dredged up decades after the fact, long after the story had been embedded in baseball history. One of the Cardinals, backup first baseman Dick Sisler, told the historian Jules Tygiel, “Very definitely, there was something going on at the time whereby they weren’t going to play.”21

In 1997, the 50th anniversary of Robinson’s debut, ESPN’s Outside the Lines reported that it had interviewed 93 of the 107 surviving players on other National League teams. Only three of them — all members of the Cubs — claimed that their club had voted to strike as part of a league-wide boycott on Opening Day. Five players — one Cub, two Pirates, and two Phillies — said their teams had voted against a strike. The other 85 either denied knowing anything or wouldn’t comment.22

The Cardinals could never escape the stain on their reputations. After a 1990 book, The Ballplayers, named him and Slaughter as leaders of the strike plot, 82-year-old Terry Moore had his lawyer write to the publisher demanding a retraction.23

THE PLOT THINS

Overlooked in the he-said, he-said is one incontrovertible fact: a team that refused to play against Robinson would forfeit the game. The Cardinals and Dodgers had tied for first place in 1946, when St. Louis won the pennant in the majors’ first playoff, and the teams were favored to fight it out again in 1947. A pennant meant a lucrative payday, a World Series share worth $5,000 or more for players, many of whom made less than $10,000 a year. It’s hard to imagine the level-headed Moore and Marion agreeing to give away games and endanger their Series checks. Marion said, “I never heard such a stupid thing in my life.”24

Overlooked in the he-said, he-said is one incontrovertible fact: a team that refused to play against Robinson would forfeit the game. The Cardinals and Dodgers had tied for first place in 1946, when St. Louis won the pennant in the majors’ first playoff, and the teams were favored to fight it out again in 1947. A pennant meant a lucrative payday, a World Series share worth $5,000 or more for players, many of whom made less than $10,000 a year. It’s hard to imagine the level-headed Moore and Marion agreeing to give away games and endanger their Series checks. Marion said, “I never heard such a stupid thing in my life.”24

The Cardinals would not strike without Moore and Marion’s approval. Moore, the captain since 1941, was nearing the end of his career, but he still ruled the clubhouse as the enforcer of the Cardinals code: take the extra base, break up the double play, don’t even say hello to opposing players. Marion, a quieter figure, was the team’s player representative and had been the primary architect in creating the players pension plan the year before.

Who would stand against them? The 26-year-old Musial was the biggest star in the National League, but he described himself as a follower of his veteran teammates, not a leader.25 Slaughter, a roughneck throwback to the Gashouse Gang of the 1930s, was close to Moore — they remained lifelong friends — and would never oppose the captain.26 No doubt Harry Walker was doing a lot of talking, parroting his big brother. Unlike Dixie, Harry, an annoying individual who ran his mouth all the time, was no leader. He was traded just before the Cardinals’ first series in Brooklyn because manager Dyer wanted a more powerful bat in the outfield.

Besides Moore, Marion, and possibly Musial, no Cardinal had the clout to organize a strike. And the idea that a strike by one team would spread to the other seven sounds, frankly, crazy. Dixie Walker of the Dodgers was a respected leader who was elected National League player representative, but he had not led his own club out on strike. (Walker changed his tune about playing with Robinson. He gave the rookie batting tips and told Rickey he didn’t want to be traded. Rickey traded him anyway, after the 1947 season.)

Woodward’s scoop won’t die because it dramatizes the terrible burden Robinson had to carry in the face of opposition even from his peers. Robinson did endure indignities that no human should have to bear. On the day Woodward’s story appeared, Robinson was turned away from the Benjamin Franklin Hotel in Philadelphia, where the Dodgers had reservations. That same day he posed, with gritted teeth, for a photo with Ben Chapman, who had been ordered to make peace. Around the same time Rickey revealed that letters threatening Robinson’s life had been forwarded to the FBI.

ALL TALK, NO ACTION

What is true, and what is “barnyard vulgarism”? Did Sam Breadon believe a strike by the Cardinals was a genuine threat? Yes, but he always believed doom was lurking around every corner. Did Moore and Marion convince him there was nothing to it? Yes. Were Moore and Marion lying? Circumstantial evidence says they were telling the truth.

Of course, many players didn’t want Robinson in their midst, and they weren’t all Cardinals or southerners. Carl Furillo of Pennsylvania later acknowledged his opposition (and regretted it) and Ewell Blackwell of California was openly hostile, to name just two.27 But it’s a giant leap from saying “we gotta do something” to organizing a league-wide strike

If there was a conspiracy, the sparse evidence indicates it most likely originated with Dixie Walker during spring training. As NL player rep, he had a network of contacts around the league. But the most specific claim of Walker’s involvement is suspect. Eighty-year-old former Cub Dewey Williams told ESPN that Walker planned to trigger the strike with phone calls to other teams as soon as Robinson took the field on Opening Day: “Everybody was in the clubhouse sitting around and waiting for Dixie to call, which we thought sure he was gonna do.”28 He didn’t. No one has corroborated Williams’s version.

If there was such a plot, Walker either ran into opposition, changed his mind, or got cold feet. A strike faced an insurmountable hurdle. All the Dodgers and all the players on all seven other teams would have to go along — at the risk of suspension without pay, at the risk of forfeiting games, at the risk of public condemnation. As Terry Moore said when the story first surfaced, “I think I know enough to realize there is no such thing as a partial strike.”29

Pittsburgh Courier writer Wendell Smith, Robinson’s traveling companion in 1947 and the ghostwriter of his first autobiography, had no motive to play down the incident, but he did. He said it “was greatly exaggerated and made a better newspaper story than anything else.”30

Ford Frick probably came closest to the truth. “You know baseball players,” he told Jerome Holtzman. “They’re like anybody else. They pop off. Sitting around a table with a drink or two they commit many acts of great courage but they don’t follow through.”31

WARREN CORBETT is the author of “The Wizard of Waxahachie: Paul Richards and the End of Baseball as We Knew It,” and a contributor to SABR’s BioProject. He became a baseball fan when he saw Jackie Robinson dancing off base on a snowy black-and-white TV set. This article was selected as a winner of the 2018 McFarland-SABR Baseball Research Award.

Notes

1 Stanley Woodward, “Views of Sport,” New York Herald Tribune, May 9, 1947, reprinted in The Sporting News, May 21, 1947: 4.

2 Roger Kahn, The Era, 1947-1957: When the Yankees, the Giants, and the Dodgers Ruled the World (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1993), locations 855 and 4929.

3 Bob Broeg, “Remembrance of Summers Past,” in John Thorn, ed., The National Pastime (SABR, 1982), 22.

4 Jules Tygiel, Baseball’s Great Experiment: Jackie Robinson and His Legacy (New York: Vintage, 1984), 186.

5 Red Barber, 1947: When All Hell Broke Loose in Baseball (Garden City, New York: Doubleday, 1982), 175.

6 Woodward’s May 10 follow-up story was also reprinted in The Sporting News, May 21, 1947: 4.

7 Ford Frick, Games, Asterisks, and People (New York: Crown, 1973), 97.

8 Jerome Holtzman, The Commissioners (Kingston, New York: Total Sports, 1998), 101.

9 Kahn, Rickey and Robinson (New York: Rodale, 2014), 259.

10 “Unfortunate Booing of Walker,” Brooklyn Eagle, April 13, 1947: 20.

11 Sid Keener, “Breadon Flatly Denies Cards Wanted To Bar Robinson In Brooklyn Series With Birds,” St. Louis Star-Times, May 9, 1947: 25.

12 “Strike Threat Over Robby Ended—Frick,” Brooklyn Eagle, May 9, 1947: 17.

13 Ibid.

14 Broeg, “Cardinal Players Deny They Planned Protest Strike Against Robinson,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, May 9, 1947: 9C.

15 Kahn, The Era, 57.

16 Holtzman, 101.

17 Quoted in Kahn, Rickey and Robinson, 264.

18 “The Negro Player Steps on the Scales,” The Sporting News, May 21, 1947: 14.

19 Sam Lacy, “Strike Against Jackie Spiked,” Afro-American (Baltimore), May 17, 1947: 1.

20“A Conversation with Jerry Izenberg, Part III,” https://edodevenreporting.wordpress.com/2015/10/19/a-conversation-with-jerry-izenberg-part-iii-influences-and-more-memories/, accessed January 31, 2016.

21 Tygiel, 187.

22 Outside the Lines: Jackie Robinson’s Legacy, ESPN, February 28, 1997. Hank Wyse, Dewey Williams, and one unidentified player said the Cubs voted to strike. Phil Cavaretta of the Cubs, Al Gionfriddo of the Pirates, and Andy Seminick of the Phillies said their clubs voted to play; the other two players were not named.

23 W. Ray Raleigh letter to William Morrow and Company, June 23, 1994, in Moore’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame library, Cooperstown, New York.

24 Peter Golenbock, The Spirit of St. Louis (New York: Harper Entertainment, 2000), 384.

25 Kahn, The Era, 56.

26 Later in 1947 Collier’s magazine published its own scoop, alleging that Musial and Slaughter had fought over the strike, and Slaughter had put Musial in a hospital. Musial did go to a hospital just as Woodward’s story was breaking, because he was sick with appendicitis. People who saw him shirtless said he showed no sign of a beating.

27 Kahn, Rickey and Robinson, 120; Arnold Rampersad, Jackie Robinson: A Biography (New York: Random House, 1997), 183.

28 Outside the Lines. Williams died in 2000.

29 Broeg, “Cardinal Players Deny.”

30 Tygiel, 188.

31 Jonathan Eig, Opening Day: The Story of Jackie Robinson’s First Season (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2007), 94. Eig found Frick’s unpublished comment in Jerome Holtzman’s notes of the interview.