‘When You Come to a Fork in the Road, Take It’: Who Took the Cycle or Quasi-Cycle?

This article was written by Herm Krabbenhoft

This article was published in Spring 2018 Baseball Research Journal

Choices … Decisions: A player has already connected for one double, one triple, and one homer in the game and needs only a simple single in his next plate appearance to achieve the cherished cycle—one of baseball’s rarest accomplishments and one that will inscribe his name permanently in the record books. If he comes through with a line drive that lands safely in the right-center field gap and bounds crisply and cleanly to the warning track—a sure double or possibly even a triple—should he stop at first base? Should he be content with a lusty single and claim the accolades for the cycle, or should he bypass the cycle and continue on to collect an extra-base-hit?

Because a baseball game “ain’t over ’til it’s over” and because there “ain’t no ‘I’ in TEAM,” a player should always strive to maximize his progress toward scoring a run—irrefutably the most important statistic in baseball. Regardless of the score or game situation, a player whose goal is to help his team win should, when confronted by the “fork in the road” described above, always “take it” and not settle for a single.

There are personal consequences for a player making that choice. He passes up being recognized for eternity in baseball’s record books as one of the rare hitters of a cycle, whereas if he takes the double (or triple), he gets a fleeting “atta-boy”—even though a double (or a triple) is always more valuable than a single.

Shouldn’t there be some kind of enduring recognition for a player who connects for four long hits—with at least one homer, at least one triple, and at least one double—in a game? In a prior Baseball Research Journal article, I termed such a performance a “quasi-cycle.”1 In the present article I focus on those players who encountered the “fork in the road.” Some chose the extra base hit while others stopped at first with an offensive-indifference single to complete the traditional cycle. This article considers cycles and quasi-cycles achieved during the post-Deadball Era, 1920 through 2017.

Research Procedure

According to Retrosheet, 255 cycles were hit 1920–2017.2 I have identified 73 quasi-cycles hit during the same period.3 The principal research procedure I followed began with generating two lists of players: (1) those players who completed their cycles with a single; and (2) those players who needed a single to complete their cycle—but instead stretched their fourth hit to a double or a triple. To compile these two lists, I examined the sequences of hits in the cycles and quasi-cycles. Most of this information can be found in the play-by-play (PBP) descriptions on Retrosheet. For the games for which the PBP information was not on Retrosheet, the requisite hit sequences were obtained from the game accounts presented in various newspaper articles. (Tables A-1 and A-2 in the Appendix, available on the SABR website, contain this hit-sequence information.) The final step was to examine the descriptions given in the pertinent newspaper accounts of the critical single, to ascertain the nature of the hit and how the hitter reacted to it. For example, was it a robust outfield gapper that could have been a double (or a triple) or was it a scratch infield hit—or something in between?

Results

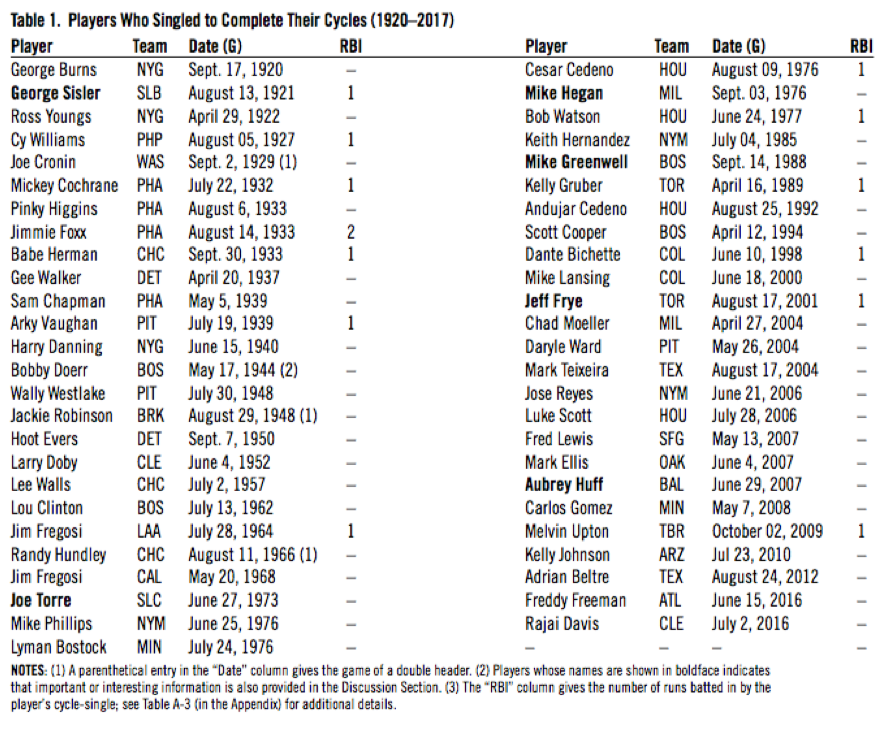

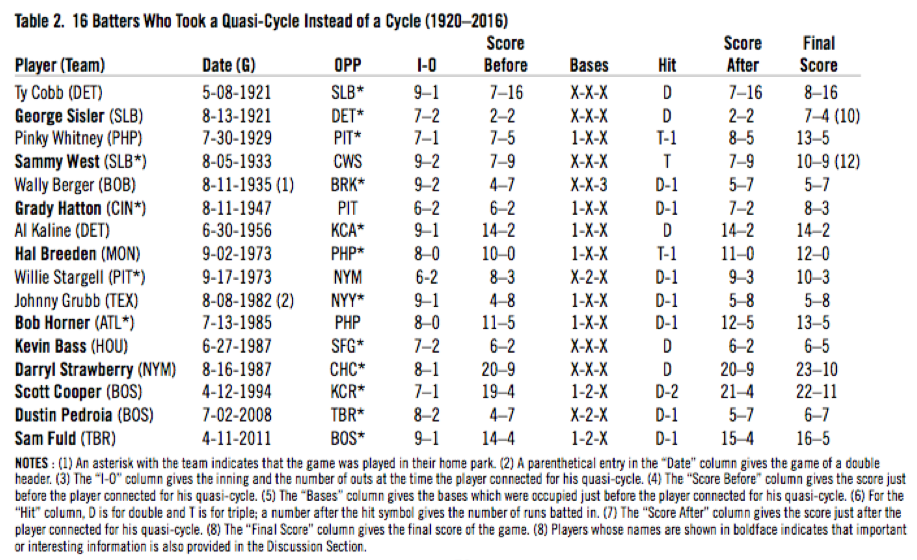

According to my research, 51 players completed their cycles with a single, 1920–2017. See Table 1 for the list of them (and see Table A-3 in the online appendix for complete details for each of these 51 cycles). By contrast, 16 players achieved a quasi-cycle by hitting a double or a triple instead. See Table 2.

Table 1. Players Who Singled to Complete Their Cycles (1920–2017)

Table 2. 16 Batters Who Took a Quasi-Cycle Instead of a Cycle (1920–2016)

Discussion

As indicated in Note 2 in Table 1, the names of some of the players are shown in boldface. That’s because there are important and/or interesting aspects associated with their cycles which merit discussion. Let’s begin with cyclist Jeff Frye.

Jeff Frye – As shown in Table 1, fourteen of the cycle-singles were RBI singles. Only one of those cycle-singles knocked in a runner from first base—the one hit by Toronto’s Jeff Frye on August 17, 2001. Frye was the second Blue Jay to achieve the feat. (The first, Kelly Gruber, will become important to our discussion shortly.) Frye came to bat in the bottom of the seventh inning with the Blue Jays leading the Rangers, 10–2. He’d already collected a second-inning triple (“when Texas Rangers right fielder Ricky Ledee misplayed his blooper, letting it bounce over his head”), a fifth-inning double (“when Ledee flailed helplessly at his hit”), and a sixth-inning roundtripper.4 With Homer Bush on first base with two outs in the seventh, Frye battled Texas hurler Kevin Foster to the limit before lining a full-count pitch into the gap in right-center field. It looked like a sure double and Bush easily sped all the way around the bases to home. But Frye, heeding the directions of first base coach Garth Iorg, stopped with a “single” to complete his cycle. Here are some of the comments made in the press about Frye’s “fork-in-the-road” cycle:

- “With the Toronto Blue Jays’ 11th run en route to the plate in last night’s 11–3 throttling of the Texas Rangers, Frye could have, perhaps should have, gone to second with what would have been an easy double into the gap in right-centre field. Instead the 34-year old journeyman infielder held up at first and became only the second Blue Jay to hit for the cycle.”5

- “I was looking at Garth and yelling, ‘What do I do? What do I do?’—and he goes ‘Stop! Stop!,’” Frye said. “And before I went up, I asked [coach] Cito Gaston what do I do if I hit a ball like that, and he said, ‘Stay on first. Tell them I told you to.’ So, if he says it’s all right, then it’s all right.”6

- “When he hit first base he asked me what he should do,” Iorg said. “I told him, ‘Stay right here.’”7

- “As far as Iorg and Jays manager Buck Martinez are concerned, there was nothing tainted about Frye’s feat with the bat. ‘It’s a cycle, that’s got nothing to do with it,’ Iorg said. ‘It (stopping) didn’t alter the game in any way.’ Added Martinez, ‘As one-sided as it was, it wasn’t a bad idea. It was a big boost to everybody. I don’t have any problems with it and I don’t think anybody in the park did.’”8

- “After he had his double I said, ‘All you need now is a homer and a single,’ and we both kind of laughed,” Martinez said. “Then he got the home run and we were all pulling for him when he came up that fourth time.”9

- Frye also said, “Bobby Jones [the Rangers third base coach] told me after I’d homered that if the score wasn’t close, and I had a chance, I should settle for a single. So, I figured with two coaches telling me that, it must be okay.”10

- Jays closer Billy Koch had joked with Frye before he hit his [sixth-inning] homer. “He said hit a home run next time and [then] bunt for a hit,” said Frye. “But I said, ‘You can’t bunt when you’re up by five runs.’” Toronto Star reporter Geoff Baker wrote, “That kind of adherence to baseball’s ‘unwritten rules’ went out the window by the seventh inning.”11

- “I was hoping he’d cut it off,” Frye said of the despair he felt watching the ball scoot past Ledee and to the wall. Frye then added, “lt’s something I’ll never forget.”12

- Blue Jays manager, Buck Martinez, said, “He’s such a professional; he didn’t know if it was appropriate to stop at that point, but the game was pretty one-sided. It’s a pretty unique opportunity to play nine years and have a chance for a cycle.”13

- Texas first baseman Rafael Palmeiro said, “The game was pretty much at hand for them, and everybody wanted it, so I don’t see a problem with it. He hit the ball into the gap, but I’m happy for him. It’s a little bit controversial, but he did it, and nobody can take it away from him.” Palmeiro added that he “would probably do the same thing in a similar situation.”14 (In his Hall-of-Fame-numbers career, Palmeiro did not hit for a cycle nor a quasi-cycle.)

- “If purists are troubled by Frye’s shrinking of a double into a single for the sake of a small piece of fame, he has company. When Gruber performed his feat against the Kansas City Royals at Exhibition Place, he also remained at first instead of legging out a double. ‘The game’s out of hand. What’s the point?’ Gruber said of Frye’s achievement. ‘Opportunities like that don’t come around too often. What the heck.’”15

Kelly Gruber – Here’s the story on Gruber’s feat, as reported in The Sporting News:

- “Gruber started his cycle with a solo homer off Floyd Bannister in the first inning and followed that with a two-run double in the second. Against righthander Tom Gordon in the seventh, he hit a two-run triple. His sixth RBI came on his last hit, a bloop single off Jerry Don Gleaton in the eighth.”

- “In addition to the congratulatory handshakes he received from teammates upon completing the cycle, Gruber learned he faced a possible fine from the Jays’ kangaroo court. His last hit might have gone for a double under other circumstances, but Gruber stayed at first to get the single he needed [to complete the cycle]. ‘If it’s a tie game, sure I’ve got to try for it (a double),’ said Gruber. But with the Jays up by six runs at that point, he could afford to stay at first. However, reliever Tom Henke joked that Gruber’s actions could merit a fine. ‘It’s automatic,’ Henke said. ‘Stretching a double into a single was the way chief justice Mike Flanagan saw it.’”16

Here’s what Gruber had to say after his cycle-game, as reported in the Kansas City Times:

- “I put a lot of pressure on myself because I wanted that single,” Gruber said. In his game-account article, Dick Kaegel wrote, “Although Gruber might have had a chance of stretching the hit into a double, he reined in at first.” And Gruber added, “Any other time I might have tried for a double, but right then it didn’t mean much.”17

- Gruber looked back at his cycle in an article in the Toronto Sun and commented: “I have had a lot of fans tell me I should have been on second that day I hit mine,” Gruber said. “It was a hot day, the turf was spongy, really bouncy and I hit the ball up. I was so busy talking to it, telling it to get down for my single, that I just got to first when the ball hit (the turf),” Gruber said. “The outfielder jumped up and caught it on the bounce. Otherwise it’s over his head and I have to go to second. I could have gone and probably would have made it, but I didn’t. Everybody says you should have gone, but it’s such a great opportunity.”18

- With respect to Frye’s cycle, Gruber (who was at the game) was shouting out advice from just beside the Jays dugout. “I was screaming at him, ‘Stop! Don’t Go!’ And so was Garth. I wanted him to get it.”19

For 49 of the 51 players listed in Table 1, their “cycle-clinching singles” were ordinary run-of-the-mill one- base knocks—see Table A-3 in the Appendix for all the details. Here is some “rest-of-the-story” information about some of the other Table 1 cycle-achieving players.

Mike Greenwell – In contrast to Gruber and Frye, here’s what Mike Greenwell of the Boston Red Sox said about his own cycle (September 14, 1988): “Somebody asked me jokingly if I hit one in the gap would I stop at first and take the single. I said no way; I’d be running to second and third or wherever I could get.” Fortunately for Greenwell, he dumped a clean-cut single into right field. “I didn’t have to make that decision.”20 When Greenwell hit his cycle-single in the bottom of the eighth inning, the Sox were leading the Orioles by a single run, 4–3 (which turned out to be the final score).

Aubrey Huff – Aubrey Huff almost precluded himself from achieving the cycle. Moments before he smacked a bloop single into shallow center, he smashed a pitch inches foul down the third base line. If it had been fair, Huff could have easily reached second. Like Greenwell, he said he wouldn’t have stopped at first—even to complete the cycle. “In that situation, I’m going for two [bases],” Huff said. “I feel like you cheat the game if you stop at first. I wouldn’t even count that as a cycle.”21

Joe Torre – Joe Torre collected a cycle with the St. Louis Cardinals on June 27, 1973, in Pittsburgh. Torre had picked up the three extra-base hits needed in the first four innings, and he’d have at least two chances to get the simple single. But he grounded into an around-the-horn double play in the fifth and then grudgingly walked to lead off the eighth. At that point in the game, with the Cards leading the Pirates, 11–4, the likelihood of Torre getting another shot was slim. In the top of the ninth he’d only come up if two men reached base ahead of him. As described by St. Louis Post-Dispatch writer Neal Russo, “Torre asked manager Red Schoendienst to give him the rest of the night off. Schoendienst refused. The first two men made out in the ninth, and Torre’s hopes looked dismally bleak. But then the next two Cardinals drew walks, which brought him to the plate … ” and “he jumped on the opportunity with a chopper single past the mound.” After the game, Torre said, “You have to give Red an assist; I’m glad he ignored me. I didn’t think I’d ever hit for the cycle because I’m not a triples hitter. I was pressing like crazy for the single.” Russo then asked, “Would you have stopped at first on a cinch double if you had hit one in the ninth?” Torre’s response: “I might have. I’ve never come this close to hitting for the cycle.”22 Some other Torre comments were reported by Charley Feeney in the game-account article he wrote for the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette: “It’s the first time I’ve ever hit for the cycle. I’m not exactly a triple man, you know. It would have been a kick, though, if a lousy single had kept me from getting it.”23 And, in the article by Jeff Samuels for the Pittsburgh Press, Torre was quoted: “If I would have hit that last ball off the wall, I would have stopped at first base.” Torre, who clapped his hands all the way to the bag after getting his single, added, “It was a 3–1 pitch, and I sure wasn’t going to take another walk.”24

Mike Hegan – Mike Hegan was also asked the “fork-in-the-road” question after he hit his cycle. The game was against the Detroit Tigers in the Motor City. Hegan smacked a two-run double in the first, a solo homer in the third, and a bases-loaded triple in the fourth. Mike Gonring of the Milwaukee Journal wrote: “Then in the sixth, fully aware that he needed a single to complete it, he hit a line drive to left that fell in. It looked for a moment as if he might go to second. ‘Not with my wheels,’ Hegan said later. And he stopped, the cycle completed.”25 Gonring continued: “What would he have done, somebody wondered, if he had hit what could have been an extra base hit? ‘I don’t know,’ Hegan said, laughing. ‘I guess I could have tripped or fallen down. I knew the fourth time up I had a chance to do it. I just wanted to make contact, to keep the ball in play. It wasn’t time for me to hit the ball out of the ballpark, with one out and nobody on.’” Hegan had two more plate appearances in the game—two chances to connect for another extra base hit and add a quasi-cycle to his collection. But one resulted in a walk, and in the other “he hit a fly ball to center, not too deep, not too shallow. The bases were loaded and the runners sprinted toward the plate, but the ball floated into the glove of center fielder Ron LeFlore [to end the inning].” And, here’s neat a tidbit included in the game story written by Lou Chapman of the Milwaukee Sentinel: “Hegan, who was obviously thrilled, said, ‘It was more so after I asked Henry Aaron [who did not play in the game] if he had ever done it. And he said no. So that gives me something on him.’”26

Moving on now to those 16 players who bypassed the cycle, as shown in Table 2, three of them made it all the way to third with a triple, while the other 13 doubled. Here’s some additional information on those whose “fork-in-the-road” decision was the quasi-cycle.

George Sisler – In Detroit, on August 13, 1921, in the seventh inning with nobody on and two outs, Sisler smacked his second double—a drive to right field—to complete his quasi-cycle. With the score tied (2–2), it was important to get in scoring position, even though the next batter, Ken Williams, flied out to end the inning. There was still time left for Sisler to try for the cycle. In the ninth inning, with the Browns now leading by a 3–2 score, Sisler stepped into the batter’s box with Johnny Tobin on second base with two outs. He slapped a single to right field to bring home the runner. So, Gorgeous George accomplished both a quasi-cycle and a traditional cycle in the same game.

Sammy West – With the Browns trailing the White Sox, 9–7, in the bottom of the ninth on August 5, 1933, there were two outs and the bases were empty. West was the last hope for St. Louis. And West came through in the do-or-die challenge and belted the ball to center. Rather than stopping at first with a cycle for himself, he hustled all the way to third. He scored when the next batter was safe on an error. Two more singles produced the game-tying run. The Browns went on to win the game in the twelfth inning. And while there was no mention in the various St. Louis and Chicago newspapers about West having bypassed a chance at the cycle, it was noted in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat that he did tie the modern major league mark for most long hits in a game (4). West had one more chance to complete the cycle—in the eleventh inning, with a runner on first (Lin Storti) and nobody out. West laid down a sacrifice bunt instead of swinging away.

Grady Hatton – While he decided to bypass the cycle when he doubled in the sixth inning (after having homered in the first, doubled in the third, and tripled in the fourth), he had no decision to make when he reached first base safely in the eighth inning with Bucky Walters on third base and Frankie Baumholtz on second base (after each had singled and Benny Zientara had laid down a sacrifice bunt). Hatton was given an intentional base on balls. That walk was not “as good as a hit.”

Hal Breeden – Primarily a part-time player (mostly first base) with the Cubs and Expos 1971–75, Breeden had only one four-hit game in his career—his quasi-cycle game, on September 2, 1973. In that game he walloped a three-run homer in the first, struck out in the second, collected (as described in the Philadelphia Inquirer) “a looping hit which Phillies center fielder Del Unser misplayed into a triple” in the fourth, and smacked an RBI double in the sixth, thereby setting the stage for a nifty reverse-order-cycle. Then, as reported in The Sporting News, “Hal Breeden was about to leave the dugout for warmup swings prior to his fifth time at bat against the Phillies. The score was Expos 10, Phillies 0 in the top of the eighth. Breeden’s first base platoon-mate, Mike Jorgensen, called him back and whispered, ‘Listen Bo. Just hit the ball good and stop at first base. That’ll give you the cycle.’ And sure enough, he laced into a Barry Lersch serving for a tremendous drive which appeared to be headed out of the stadium. The ball hit against the fence, but Breeden didn’t stop at first. In fact, the Georgia strong boy didn’t stop until he was at third base. ‘I thought about stopping,’ Breeden said, ‘as I got to first. Then I figured I’d have to explain it to Gene (i.e., Montreal Manager Mauch). It was better to keep on running.’”27

Bob Horner – The 1978 National League Rookie of the Year, Horner spent nine years with the Braves and one with the Cardinals. He had three four-hit games that were each one hit short of the cycle (including his quasi-cycle). In the other two games, the triple and the home run were the missing hits once each. With regard to his July 13, 1985, quasi-cycle game, Chris Mortensen (a staff writer for the Atlanta Constitution) mentioned to Horner that if he had stopped at first base on his eighth-inning double, he would have been the first Brave since 1910 to hit for the cycle. “I couldn’t have done that,” Horner said, shaking his head. “The ball rolled to the fence.”28

Kevin Bass – “Bass lights up Candlestick for Astros!” That was the Sports section headline in the Houston Post on June 28, 1987. The sub-headline was, “Houston right fielder gets 4 extra-base hits in 6–5 win over Giants.” The game story by Ivy McLemore provided the following description:

Bass began his record-setting performance with with a two-run double in the first inning against Kelly Downs. In the third, Bass grounded a triple down the right field line. The Astros pulled away with three runs in the fifth on singles by Bill Doran and [Denny] Walling, a passed ball charged to catcher Bob Brenly and Bass’s two-run homer into the right-field seats. “I really started thinking about the cycle after the triple in the third,” Bass said. “And once I hit the home run, all I needed to do was dink one in for a single.” The game’s biggest mystery was solved in the seventh, when Bass went to the plate against left-hander Mark Davis, needing only a single for the cycle. For a moment it appeared as if the right pieces—and hits—would continue to fall into place for Bass. He lifted a weak fly to shallow left field, where Jeff Leonard lost a battle with the sun and had the ball drop in front of him. Bass trotted into second with his second double to cap off a four-hit performance. “You can’t stop in a situation like that” Bass said. “You have to go. It’s a neat thing to say you’ve hit for the cycle in the major leagues, but that’s a goal a lot of players never reach.”29

In the game account presented in the Houston Chronicle, Bass was quoted: “After I hit the triple (in the third inning) I was thinking about the cycle. I guess the best way to do it is get the triple and homer out of the way early. That’s the hard part. If you get them, then you might dink one in somewhere. I did, but I dinked it too good, I guess. The cycle is something that’s a neat thing for the fans and for an individual.”30

Darryl Strawberry – The 1983 NL Rookie of the Year, Strawberry played in the majors for 17 years, mostly with the New York Mets, but also with the Los Angeles Dodgers, San Francisco Giants, and New York Yankees. He fashioned two four-hit games and one five-hit game, each lacking just one hit for the cycle, including his quasi-cycle game. In both of the other games the triple was the missing hit. In his quasi-cycle game, August 16, 1987, Strawberry hit a double in the third inning, a home run in the fourth, and a triple in the sixth. Then, as described in The Sporting News, “With the Mets leading 20-9 in the eighth, Strawberry came to bat needing a single to complete the cycle. He hit a liner into the left field corner and [first base coach Bill] Robinson discreetly signaled for him to stop at first, but Strawberry charged on to second. ‘That was a double all the way,’ he said. ‘You can’t think about what you’ve done when you get a hit like that.’”31 Jack O’Connell has a similar account in the New York Daily News: “Strawberry hit a line drive past left fielder Brian Dayett and never hesitated rounding first, ignoring the cycle and getting another double. ‘Bill [Robinson] gave me the stop sign at first,’ Strawberry said, ‘but I was running all the way.’”32 Bob Klapisch wrote in the New York Post: “Darryl Strawberry almost hit for the cycle. All Strawberry needed was a single in his last at-bat, but he passed up the chance to stop at first when he doubled to left. ‘No, that’s not the way to play baseball,’ Strawberry said. ‘Bill [Robinson] wanted me to stop at first, but there was no way I was going to do that. That ball [hit to deep left] was a double. I didn’t even stop to think about it.’”33 So, there’s a chasmic contrast between Strawberry’s quasi-cycle and Jeff Frye’s cycle, Frye obediently followed the first base coach’s directions and stopped at the initial sack with a single to complete the cycle, while Strawberry defiantly ran through the first base coach’s stop sign. Another interesting aspect of Strawberry’s quasi-cycle is that he did, in fact, have a safe one-base plate appearance—he walked in the first inning! Another example of a walk not being “as good as a hit.”

Scott Cooper – In his seven-year career in the majors (1990–95, 1997), mostly with the Boston Red Sox, the stars aligned only once, on April 12, 1994, permitting Cooper the opportunity to achieve both the quasi-cycle and the cycle in the same game. When he came to bat in the seventh inning, he only needed a single to complete his cycle. His first crack had come in the sixth inning. With the bases loaded and two outs, he was safe on a fielding error by Kansas City Royals shortstop Dave Howard. Then came his seventh-inning “fork-in-the-road.” With the Red Sox leading, 19–2, two on and one out, Cooper belted the ball to deep right field, driving home both Scott Fletcher and Tim Naehring and taking second on a clean double, thereby passing up the cycle—but getting a quasi-cycle! However, he got another chance in the ninth. Leading off, he connected for a clean simple single to complete the cycle. Here’s what was reported in the Kansas City Star by Dick Kaegel: “Things got so bad [for Kansas City] that the Royals had shortstop Dave Howard pitch the final two innings, and it was against Howard that Cooper singled in the ninth, completing the cycle.” Cooper reportedly said, “Everybody on the bench was telling me, ‘You need a single. Lay one down.’” But with the Red Sox up, 22–8, he wasn’t about to bunt. “Howard threw me two nasty changes, but on 0–2 he came back with a fastball and I was able to hit it,” Cooper said.34 Cooper’s fifth-inning triple was also special. He was credited with a triple after he was put out at the plate trying for an inside-the-park home run. Had he been safe at home, he would have missed out on both the quasi-cycle and the traditional cycle.

Dustin Pedroia – The recipient of the 2007 AL Rookie of the Year Award and the 2008 AL Most Valuable Player Award, Pedroia has spent his entire career with the Boston Red Sox. With respect to his quasi-cycle, which he achieved on July 2, 2008, Pedroia commented (as reported by Gordon Edes and Amalie Benjamin for the Boston Globe): “I was trying to go up there and hit the ball hard the last two times I got up. When I got back after I hit the double, guys were joking, ‘You should have fallen down or something.’ But I just play the game.”35

Sam Fuld – An eight-year player in the majors (2007, 2009–15) with four teams (Cubs, Rays, Athletics, and Twins), Fuld achieved his quasi-cycle on April 11, 2011. Here’s what Michael Vega included in his game story for the Boston Globe: “Fuld stroked a pitch into left field but stretched it into a double. Asked if he considered stopping at first, Fuld replied, ‘Thought about it a little bit, but only jokingly. If lead runner Brignac had tripped and fell he would have been the goat or whatever. You can’t do that. That was a sheer double. I’ll take those any day.’”36

Concluding Remarks

In addition to the 16 players who responded with a repeat double or a duplicate triple when confronted with the “fork-in-the-road” choice of a cycle or quasi-cycle, six players earned the quasi-cycle by hitting a second home run—Lou Gehrig (July 29, 1930), Johnny Mize (July 3, 1939), Daryl Spencer (May 13, 1958), Hank Aaron (May 3, 1962), Larry Walker (May 21, 1996), and Carl Everett (August 29, 2000). Each of these second homers was an “in-the-seats” roundtripper. These batters had no choice but to run all the way around the bases. Of these six, only Gehrig and Mize were successful in hitting for the traditional cycle at some other time in their careers.

Sixty-five players have needed a single to claim the cherished cycle: the 51 listed in Table 1 plus 14 of the 16 players listed in Table 2 (excluding Sisler and Cooper who are included in Table 1). As shown in Table A-3 in the Appendix, 47 of the 65 players connected for an “ordinary one-base hit” which essentially obviated making a choice. Thus, these 47 players had to “settle” for a traditional cycle. The other 18 players belted gappers that afforded them the opportunity to choose either a long hit (double or triple) for a quasi-cycle or a “super-single” for the cycle. For 16 of these players—Cobb, Sisler, Whitney, West, Berger, Hatton, Kaline, Breeden, Stargell, Grubb, Horner, Bass, Strawberry, Cooper, Pedroia, and Fuld—the better choice was the extra-base hit and the resulting quasi-cycle. Indeed, for West, his quasi-cycle choice contributed significantly to a come-from-behind victory.

Only three of these 16 players also achieved a classic cycle at another time—Sisler (twice, including his quasi-cycle game), Stargell, and Cooper (in his quasi-cycle game). For the other two players—Gruber and Frye, choosing the cycle over the quasi-cycle was the “better” choice, because each earned everlasting fame.

As Rafael Palmeiro said about Frye’s cycle, “It’s a little bit controversial, but he did it, and nobody can take it away from him.” There is no asterisk attached to it in the lists given in the various record books or websites. Curiously, in the entire history of the Toronto Blue Jays franchise, only two players have connected for a traditional cycle—Gruber and Frye, while no Toronto player has hit for a quasi-cycle.37

HERM KRABBENHOFT, a SABR member since 1981, is a frequent contributor to the “Baseball Research Journal.” From 1986 through 1996 he published “Baseball Quarterly Reviews,” which presented his research on “Baseball’s Best Run Getters,” “Ty Cobb vs. Babe Ruth (Premier Hitter vs. Premier Pitcher),” “Ultimate Grand Slams,” “Ultimate Winning Pitchers,” “The Role of Fielding Errors in the World Series,” and many more.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks are gratefully extended to Keith Carlson, Dixie Tourangeau, Dave Smith, Doug Todgham, Cliff Blau, Gary Stone, Albert Hallenberg, Misty Mayberry, Gordon Turner, Jay Buck, Jerry Nechal, Amy Welch, and Dave Newman for providing scans of newspaper game accounts for the hit sequences and/or other important information for some of the players who hit cycles and/or quasi-cycles. And, it is a pleasure to acknowledge the Retrosheet volunteers who contributed to the phenomenal Retrosheet database of play-by-play information which was vital in generating the information presented in Tables 1 and 2 (as well as Tables A-1 through A-3 in the Appendix).

Notes

1. Herm Krabbenhoft, “Quasi-Cycles—Better Than Cycles?,” Baseball Research Journal (46:2, Fall 2017) 107.

2. Retrosheet, “Games/People/Parks”>”Achievements”>”No-Hitters & Cycles.” Accessed November 17, 2017.

3. As reported in Reference 1, there were 73 quasi-cycles during the 1920–2016 period. According to the information available from the “Play Index” on the Baseball-Reference website (accessed November 17, 2017), there were no quasi-cycles achieved in 2017.

4. Geoff Baker, “Frye Cycles to Jays Record,” Toronto Star, August 18, 2001, C1.

5. Scott Burnside, “Frye Cooks Up a Night of Memories,” National Post (Canada), August 18, 2001.

6. “Frye Pulls Up For Single, Gets Cycle,” Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, August 18, 2001 (Web site accessed April 30, 2017).

7. Mike Rutsey, “Very Good Frye-Day!,” Toronto Sun, August 18, 2001, 56.

8. Mike Rutsey, “Very Good Frye-Day!,” Toronto Sun, August 18, 2001, 56.

9. Mike Rutsey, “Very Good Frye-Day!,” Toronto Sun, August 18, 2001, 56.

10. Jeff Blair, “Frye Recycles Memories,” Toronto Globe and Mail, August 18, 2001.

11. Geoff Baker, “Frye Cycles to Jays Record,” Toronto Star, August 18, 2001, C1.

12. Geoff Baker, “Frye Cycles to Jays Record,” Toronto Star, August 18, 2001, C1.

13. “Frye Pulls Up For Single, Gets Cycle,” Associated Press, Los Angeles Times, August 18, 2011 (Web site accessed April 30, 2017).

14. “Jeff Frye Hits for Cycle,” Associated Press, seattlepi.com/sports, August 17, 2001 (accessed April 30, 2017).

15. Scott Burnside, “Frye Cooks Up a Night of Memories,” National Post (Canada), August 18, 2001.

16. “Gruber Rides Out Injury, Gets Jays’ First Cycle,” The Sporting News, May 1, 1989, 22.

17. Dick Kaegel, “Blue Jays ‘Reduplicate’ Royals Script,” Kansas City Times, April 17, 1989, C1.

18. Mike Rutsey, “Very Good Frye-Day!,” Toronto Sun, August 18, 2001, 56.

19. Mike Gantner, “Gruber Thinks Back,” Toronto Sun, August 18, 2001.

20. Bob Ryan, “Greenwell Savors Cycle,” Boston Globe, September 15, 1988, 94.

21. Geremy Bass, “Huff Third Player to Hit for Cycle in 2007,” MLB.com, June 30, 2007 (accessed April 30, 2017).

22. Neal Russo, “Torre’s Cycle Powers Cards,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 28, 1973.

23. Charley Feeney, “Cardinals Stagger Pirates,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 28, 1973, 13.

24. Jeff Samuels, “Cards Wallop Pirates, 15–4,” Pittsburgh Press, June 28, 1973, 40.

25. Mike Gonring, “Hegan Hot, So ‘Bird’ Not,” Milwaukee Journal, September 4, 1976, 10.

26. Lou Chapman, “‘Bird’ Lays Egg; Hegan Scrambles It!,” Milwaukee Sentinel, September 4, 1976.

27. Ian MacDonald, “Breeden, With Pounds Gone, Adds Heft to Expos’ Attack,” The Sporting News, September 22, 1973, 11.

28. Chris Mortensen, “Braves Overwhelm Phillies, 13–5,” Atlanta Constitution, July 14, 1985. Bill Collins was the Braves player who accomplished the cycle in 1910. Two years after Horner bypassed the cycle by achieving his quasi-cycle, Albert Hall did hit for a traditional cycle for the Braves, becoming the first Atlanta player to achieve the feat.

29. Ivy McLemore, “Bass Lights Up Candlestick for Astros,” Houston Post, June 28, 1987, C1.

30. Neil Hohlfeld, “Bass’ Extra-Base Binge Fuels Astros,” Houston Chronicle, June 28, 1987, Sports 1.

31. “Raines Joins the Cyclists,” The Sporting News, August 24, 1987, 26.

32. Jack O’Connell, “Strawberry Socks 29th HR, Drives Home 5 in 23–10 Runaway,” New York Daily News, August 16, 1987.

33. Bob Klapisch, “Mets Smother Cubbies,” New York Post, August 16, 1987.

34. Dick Kaegel, “U-G-L-Y,” Kansas City Star, April 13, 1994, D1.

35. Gordon Edes, “Sox Get Swept Away,” Boston Globe, July 3, 2008, C1.

36. Michael Vega, “It was a Full Day for Fuld,” Boston Globe, April 12, 2011, C2.

37. Herm Krabbenhoft, “Quasi-Cycles—Better Than Cycles?,” Baseball Research Journal (46:2, Fall 2017) 107.