Honolulu Stadium

This article was written by Rory Costello

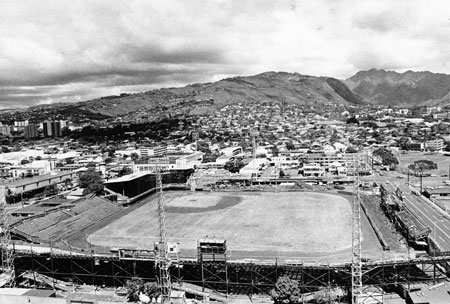

From 1926 through 1976, a wooden stadium stood at the corner of King and Isenberg Streets in Honolulu, Hawaii. It was small, with capacity of only about 25,000.1 It lacked infrastructure. It was called “The Termite Palace” for its infestation. Yet, like so many ballparks of past eras, it had a simple charm.

From 1926 through 1976, a wooden stadium stood at the corner of King and Isenberg Streets in Honolulu, Hawaii. It was small, with capacity of only about 25,000.1 It lacked infrastructure. It was called “The Termite Palace” for its infestation. Yet, like so many ballparks of past eras, it had a simple charm.

“The first time I saw Honolulu Stadium, I thought it was a little bit of Brooklyn in the tropics, with an old ramshackle Ebbets Field kind of flavor,” said Al Michaels. Before becoming a star broadcaster, Michaels called baseball games for the Hawaii Islanders of the Pacific Coast League from 1968 through 1970. “The termites were having a field day. The grass was very, very green and the stadium looked like a jewel. It had that classic ballpark aroma, with some Hawaiian delicacies in there too, like pipikaula and manapua. And the smell of beer and cigarette smoke and old wood.”

That was how Michaels opened his foreword to the 1995 coffee table book by Arthur Suehiro, Honolulu Stadium: Where Hawaii Played. A central theme of this history is community – ohana, to use the Hawaiian word.

Many nostalgic newspaper articles have reinforced this concept. As one fan said, the stadium’s very basic seating contributed to the cozy and friendly ambience. “You just felt something special, seated on the wooden bleachers. And everyone respected you, no matter who you were cheering for.”2 Chuck Tanner, who managed the Islanders in 1969 and 1970, said, “When I was there things were great. We had a close relationship with the fans and the people.”3

Honolulu Stadium served many purposes. It hosted football, rodeo, polo, boxing, track and field, stock car racing, religious revivals, and hula festivals, among other things. Popular entertainers including Irving Berlin and Elvis Presley appeared there. Yet baseball has a long and rich tradition in Hawaii, and Honolulu Stadium was a central scene. Babe Ruth and Joe DiMaggio played there, and it was the home of the Islanders from their inception in 1961 through the 1975 season. Suehiro’s definitive work covers it all in depth, but the main focus here (with some more angles) is baseball.

Honolulu Stadium was built in the Moiliili neighborhood, which became urbanized in the early 20th century. In the mid-1920s, the entire city’s population was only around 100,000. Moiliili’s population was largely Japanese. The neighborhood’s name, which comes from a local myth, shows how deeply integrated the stadium was with its setting. The Hawaiian word ˈiliˈili means volcanic pebbles, which are abundant in that area, having washed down from Manoa Stream. A quarry was once one of the main features of Moiliili.4 The field was built on a bed of the crushed basalt, and according to outfielder Mike Floyd, who played there as a visitor in the 1970s, that helped hitters – “the ball scooted.”5

The man behind Honolulu Stadium was J. Ashman Beaven (1869-1946). Beaven, who was born in Tioga County, New York, came to Honolulu in 1910. Previously, from 1905 through 1907, he had been in business in China and Japan. In 1912, he established the Oahu Baseball League, Oahu Service Athletic League and the Catholic Youth Organization. In 1925, he purchased 14 acres around the King/Isenberg location and constructed the stadium at an estimated cost of $150,000. He remained general manager until 1939.6

The new stadium officially opened on November 11, 1926. The first event was a football game, before 12,000 fans.7 Football has also long been a popular sport in Hawaii, and a lot of gridiron action took place at Honolulu Stadium over the years.

To summarize Suehiro’s background on local baseball then, in 1925 J. Ashman Beaven was managing the established Honolulu Baseball League. This league played its games at Moilili Field, right across the street from where Honolulu Stadium would stand. In May 1925, Beaven launched a new league, the Hawaii Baseball League. The six teams that defected from the Honolulu Baseball League represented Hawaii’s many ethnic groups: Japanese, Filipinos, Hawaiians, Chinese, Portuguese, and haoles (broadly speaking, whites who weren’t working-class). The new league stayed at Moiliili Field until the spring of 1927, when Honolulu Stadium’s newly built grandstand was christened.

Suehiro provided further insight into Hawaii’s local baseball scene from the 1920s through the 1950s. There were many junior circuits of different ethnicities, as well as the Commercial League, composed of squads from utility and sugar companies. Yet despite an ever-changing group of teams, the Hawaii Baseball League remained the premier local loop until it went into decline in the late 1950s.

Hawaii’s strong Asian influences were also visible in more of Honolulu Stadium’s distinctive food offerings – “grinds”, to use the local slang. Peanuts are a longtime ballpark staple, but vendors outside Honolulu Stadium sold them boiled (not just roasted) in plain brown paper bags. One good theory holds that this snack’s origin is Chinese. It’s also possible, however, that soldiers from the southern U.S. introduced this item, which remains a traditional favorite in many parts of Dixie too.8

As Chuck Tanner also recalled, “During the games, fans ate corn on the cob. They had some soup. . . won ton or something. I don’t know. And they had these sticks with beef on them.”9 That soup was saimin, a Hawaiian noodle concoction of Chinese origin with assorted other Asian flavors and ingredients. Its popularity increased broadly after it became the specialty fast food at Honolulu Stadium. Barbecue sticks are another big Hawaiian favorite, with roots in both Filipino and Japanese cooking.

“They had the best concession stands in the league,” said pitcher George Sherrod, who played there during six seasons in the 1960s and ’70s.10 Mike Floyd added, “Don’t forget the Primo Beer (local suds) in the clubhouse with slices of fresh papaya and pineapple. The clubby always had a big pot full of spicy pork and ramen for good eats.”11

On October 22, 1933, Babe Ruth played in Honolulu Stadium for the first time. It was part of a barnstorming tour that included Oahu and the Big Island of Hawaii (a leg in Japan was scheduled but fell through).12 A local Hawaiian-language newspaper, Ke Alakai O Hawaii, talked about the Honolulu exhibition a few days before, saying, “The price for entrance to see the game has not been announced, but it is certain that the fee will be a blow, because the expense to bring this man here to Honolulu is great, and we hear that his family will be coming to Honolulu as well.”13

The man who brought Ruth to the islands was former big-leaguer Herb Hunter, who had become a promoter. Hunter made the arrangements with Ashman Beaven.14 The Babe complained that the baseballs provided were “second grade” – but proceeded to smack the first pitch he faced for a homer.15 On that trip, he also met the great Hawaiian swimmer and surfer Duke Kahanamoku; a photo shows them posing together in front of an outrigger canoe, with Diamond Head in the background. As it turned out, Ruth’s Hawaiian junket cost him a chance to manage the Detroit Tigers.

In 1934, Ruth returned to Honolulu. This time he was the main attraction of an all-star squad called the All Americans, which was on its way to Japan for a month-long tour. The tour was the brainchild of Lefty O’Doul, who had fallen in love with Japan after his first visit in 1931 and went on to promote East-West baseball ties for decades. The manager was Connie Mack; the team’s other high-profile players included Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx, Earl Averill, and Charlie Gehringer. Also there was fringe catcher Moe Berg, whose exploits as a spy in Japan became renowned.

In his book about the tour, Banzai Babe Ruth, author Robert Fitts described Honolulu Stadium and its setting. “[It] was a magnificent venue for a ball game. . .just outside the bustle of downtown Honolulu. Diamond Head rose majestically above the center-field wall. Beyond the left-field wall stood Dreier Manor, a tiered white Victorian mansion.”16

With background courtesy of Art Suehiro, Fitts went on to picture the stadium’s combined configuration. “Workers had spent the past week removing the temporary football stands and re-creating the diamond. The gridiron ran from the first base foul line to left field, so permanent large grandstands, designed to seat the 14,000 football fans who packed the stadium each weekend, stood along the third base foul line and just behind the right-field wall.”17

On October 25, the All Americans defeated the Hawaiian All Stars, 8-0. Lefty Gomez pitched four perfect innings, but the local squad kept the game scoreless until the fifth. The most impressive hit (aside from the show in batting practice) was Gehrig’s homer into the right-field football stand in the seventh inning. It came on the very next pitch after he’d hooked a long drive foul.

On one of Ruth’s visits (it’s not certain which), Hawaii’s first major-leaguer got to shake hands with The Bambino at Honolulu Stadium. That was Johnny Williams, who pitched in four games for the Tigers in 1914, and continued to hurl in the Hawaii Baseball League and Commercial League in the 1920s.

Football also remained a staple at Honolulu Stadium. High-school games were big, especially the Turkey Day championship match on Thanksgiving. University of Hawaii home games were played there, as were college bowl games:

- Poi Bowl (1936-39)

- Pineapple Bowl (1940-41; 1947-1952)

- Hula Bowl (1947-75)

Between 1932 and 1961, teams from the National Football League and American Football League played in at least seven exhibition games at the stadium.18 The team known simply as The Hawaiians, part of the short-lived World Football League, also called the Termite Palace home for 1974 and part of 1975.

In 1946, as part of a Pacific tour, the great Olympic track star Jesse Owens came to Honolulu. He spoke before many civic groups and also gave free instruction to youth of all nationalities at Honolulu Stadium. Ten years after winning gold medals in Berlin, he was still fast enough to win an 80-yard dash with a horse.19

During the 1940s and ’50s, however, baseball remained unchallenged as America’s national pastime. Amid World War II, many major-leaguers were serving in the U.S. armed forces. Hawaii, which played an integral role in the war, welcomed many of these players. As author William Mead noted in his book Baseball Goes to War, Admiral Chester Nimitz himself took a personal interest in the Navy’s baseball program, with the goal of providing entertainment and boosting morale.

Art Suehiro also described how other top brass in the armed services followed Nimitz’s lead, pulling rank to bolster their teams with name players – the full list is beyond the scope of this article. He noted an irony too: at one point, Civil Defense officials and the Army Corps of Engineers considered tearing Honolulu Stadium down and building bomb shelters for neighborhood residents. But that changed when the stars arrived and fans packed the house to watch them.

It’s worth singling out one of Joe DiMaggio’s feats. After he arrived in Hawaii in June 1944, he joined the Seventh Army Air Force team. The very next day, in a 6-2 loss to the Navy team, he hit what was reputedly the longest home run in Honolulu Stadium history.20 Like many such tales, though, it’s grown fuzzy in the telling. Some say it reached Isenberg Street, some say it even landed in Dreier Manor – though the pitch was quite likely grooved. Still, it was harder for righty batters like DiMaggio to hit one out – the prevailing trade winds in left field tended to knock balls down.21 However, Mike Floyd (also a righty swinger) noted, “A hard liner could cut through.”22

As it later emerged, though, The Yankee Clipper was an unhappy man in Hawaii. He was preoccupied by impending divorce and resentful about losing a chunk of his big-league prime to the service. Stressed out, he spent several stretches in the hospital.23

After World War II ended, Honolulu Stadium continued to enjoy high-level baseball. In February and March of 1946, the San Francisco Seals of the PCL held their spring training there. The Seals were managed by Lefty O’Doul, who had already expressed his opinion a year before that Honolulu was a “natural” for a PCL franchise.24 O’Doul’s men wound up camp in 1946 by playing a series of exhibition games against a Hawaiian all-star team that had a few major-league reinforcements. The Seals returned in 1947; although that year they trained more at co-owner Paul Fagan’s ranch in Maui, they also spent 10 days at Honolulu Stadium.25 That included a five-game series with the New York Giants.26

Major-league teams (or teams featuring big-leaguers) also continued to visit. This was typically just after the season ended, as a first stop en route to Japan and other points in the Far East. Local teams often provided the opposition. The games were seldom close, but a notable upset came on October 14, 1951. Lefty O’Doul brought a team including Joe and Dom DiMaggio, Billy Martin, and Ferris Fain. Hawaii fielded a squad of players serving in the military in Honolulu, and it featured two future big-leaguers. Starting pitcher Don Ferrarese hurled in the majors from 1955 through 1962. Don Larsen played first base that night; five years later, he pitched a perfect game in the World Series.

Nearly 65 years later, Don Ferrarese (aged 86 in early 2016) still had very acute and fond memories of playing in Hawaii, earning a couple of extra bucks to afford a steak dinner once a month. He also recalled the game against the O’Doul All-Stars vividly. Though he pitched mostly for local teams, his military team was Tripler Hospital and Larsen’s was Fort Shafter. Because Larsen was such a good hitter, he stayed in the lineup when Ferrarese pitched. “The fans were great and enthusiastic,” said Ferrarese. “I’m not sure who they cheered more for, the major leaguers or the locals.”27

The hero of the game was local pitcher Ed “Tuck” Correa, who pitched scoreless ball over the last four innings. Correa struck out eight – including pinch-hitter Joe DiMaggio (who was on the verge of official retirement). The Hawaii All-Stars won, 8-6, scoring twice off Bobby Shantz, four times off Eddie Lopat, and the winning runs off Bill Werle (who later pitched for and managed the Islanders in their first season). Because the visitors had plane trouble, the game didn’t start until 10:30 PM. It ended at 1 AM. O’Doul & Co. jetted off to Tokyo the next day.28

The following October, another barnstorming major-league squad arrived – the Lopat All-Stars, headed by Eddie Lopat. This team featured Pee Wee Reese, Yogi Berra, and Robin Roberts, among others. They won all six of their games in Hawaii, the first two in Maui, the fourth in Kauai, and the other three at Honolulu Stadium (although high-school football drew bigger crowds). Both Ferrarese and Larsen again took part for the Hawaiian teams.29

To recap subsequent visits later that decade:

- October 1953: As they embarked on a tour of the Far East, the Giants beat two local teams handily. Soon thereafter the Lopat All-Stars returned. They played a three-game set against a team headed by Roy Campanella of the Brooklyn Dodgers. In the rubber game, Dodgers ace Don Newcombe (on furlough from the Army) started.30

- October 1954: The Lopat All-Stars returned for six games, without Lopat himself, who was suffering from ulcers. After a game apiece on Kauai, Maui, and the Big Island, the last three were in Honolulu. Crowds were slim.31

- October 1955: The Yankees spent a little over a week in Honolulu and Hilo as part of a 25-game tour covering Hawaii, Japan, Okinawa, and the Philippines. They won all five of their games, four of them at Honolulu Stadium. Their big star was, of course, Mickey Mantle – but Don Larsen also made his return to the stadium.32

- October 1956: After the Dodgers lost the World Series to the Yankees, they set off on a trip to Japan. En route, they won two games in Honolulu after a victory in Maui.33

- October 1958: Before small crowds on the first leg of their Pacific tour, the St. Louis Cardinals played three games: one in Maui and two in Honolulu. Reinforcements for the local team included Bob Turley, Lew Burdette, and Eddie Mathews.34

The rock ‘n’ roll era brought a different form of entertainment. In 1957, megastar Elvis Presley’s long association with Hawaii began. He came to make three movies there and performed live on various occasions, notably the worldwide telecast from 1973 called Elvis, Aloha from Hawaii. The King first arrived in the islands in November 1957, and he performed two shows at Honolulu Stadium on November 10. Those and one more the next day at Schofield Barracks were Presley’s last concerts of the 1950s.35

Still another type of spectacle was visible less than two years later. On March 12, 1959, the U.S. House of Representatives passed the bill that granted Hawaii statehood. The next day, the official ceremony to celebrate this event took place at Honolulu Stadium. A crowd of 30,000 jammed in to watch the mammoth five-hour variety show, which featured 200 grass-skirted hula dancers and bands from all four branches of the armed services.36

The story of how Class AAA baseball came to Hawaii was an odd chain reaction in the industry. Since the early 1900s, Sacramento, California had been a key PCL territory. When the New York Giants moved to San Francisco ahead of the 1958 season, though, attendance suffered in Sacramento (the Seals had been forced to relocate to Phoenix). Honolulu emerged as the prime relocation candidate – contingent on renovation and expansion of Honolulu Stadium. The stadium’s majority owners at that time (the University of Hawaii and the Associated Students of the university) were unable to raise the estimated $500,000 to $800,000 needed.37

So in turn, it appeared that a deal transferring stock in and operating control of the stadium to minority shareholders would have to take place. Legal wrangling ensued.38 Finally, however, a deal was struck in January 1961. The new owner of the Honolulu franchise, Salt Lake City businessman Nick Morgan Jr., agreed to pay annual rent of $11,000 to the Honolulu Stadium Corporation for five years. The University of Hawaii remained the majority stockholder and agreed to invest $50,000 to construct box seats and to improve the lighting and dugout facilities.39 It does not appear that a full-scale renovation ever took place; the termite damage may already have been too severe.

At the Islanders’ first home game ever, on April 20, 1961, “Honolulu Johnny” Williams was present. Williams had enjoyed by far his best pro season in 1913, when he was playing for Sacramento, and the Islanders invited a sportswriter from that city, Vincent F. Stanich, to present a plaque inscribed “The Sacramento Union Salutes Johnny Williams.” Stanich recalled that Williams was visibly moved – “He responded in a half-choked fashion.”40

Upon the team’s entry into the PCL, Nick Morgan had talked about plans to bring over Asian players and give the team international flavor. The aim was “to appeal to the cosmopolitan fans of Hawaii,” said Lefty O’Doul, who went scouting with Morgan in Japan and the Philippines.41 The closest the Islanders got that first year, though, were two Filipino-Americans whose best days were behind them. One was Bobby “The Filipino Flyer” Balcena, the California-born son of immigrants. The other was a local veteran, Crispin “Cris” Mancao. This lefty pitcher was stubby (5-foot-4, 150 pounds) and ancient for baseball. Billed as 43 years old, he was actually 46.42 A handful of other Hawaiians played for the Islanders in subsequent years. Though the team was affiliated with various big-league clubs, it had an unusual quasi-independence, especially in the late 1960s and early 1970s.

Hawaii posed logistical obstacles for the PCL and its teams. High travel costs (one of the factors that eventually doomed the team in 1987) entailed a different approach to scheduling. The team’s first broadcaster, Harry Kalas – who developed his distinctive voice and style in Hawaii through 1964 – was also known for re-creating the Islanders’ road games from a studio. The bare-bones information he received allowed Kalas free rein with his imagination.43

Hawaii’s state high school baseball championship tournaments were also held in Honolulu Stadium. One memorable moment took place in the finals of the 1962 edition. On May 18, John Matias of Farrington High hit home runs in all four of his at-bats. Matias eventually made it to the majors with the Chicago White Sox in 1970. He was also a hometown favorite with the Islanders in 1972 and early 1973.

In August 1966, Honolulu Stadium co-hosted a world amateur baseball tournament (Pearl Harbor’s Millican Field was the other venue). The tourney chairman was Rod Dedeaux, the highly respected coach at the University of Southern California from 1942 through 1986. It was a round robin between teams from the U.S., Japan, Korea, and the Philippines. Japan won and the U.S. came in second.44 Yet despite grander plans to expand scope to Europe and Latin America, this appears to have been a one-off affair.

In August 1966, Honolulu Stadium co-hosted a world amateur baseball tournament (Pearl Harbor’s Millican Field was the other venue). The tourney chairman was Rod Dedeaux, the highly respected coach at the University of Southern California from 1942 through 1986. It was a round robin between teams from the U.S., Japan, Korea, and the Philippines. Japan won and the U.S. came in second.44 Yet despite grander plans to expand scope to Europe and Latin America, this appears to have been a one-off affair.

That October, the Dodgers (by then in Los Angeles) set off on another tour of Japan. Again they stopped in Honolulu, playing two games against a team of Hawaiian minor-leaguers and retired pros that featured Mike Lum and John Matias, as well as Jack Ladra, who had played seven years in Japan. The first game’s starter was legendary playboy Bo Belinsky.45 Bo hadn’t even pitched with the Islanders that year, but the beach-and-babes lifestyle in Hawaii suited him to a T. No matter what organization he belonged to, the rakish lefty tried to wangle assignments there.

Belinsky also provided one of the more exciting days in stadium history on August 18, 1968, when he threw the Islanders’ first no-hitter. That night, amid a steady light rain, Belinsky struck out 10 Tacoma Cubs and walked four. He loaded the bases in the ninth, but right fielder Joe Gaines made a dramatic catch to preserve the 1-0 win, running up against the fence to grab John Boccabella’s long drive.

Former Islander George Sherrod was there with Tacoma. He remarked, “That short fence in right field at Honolulu Stadium with the high screen was a nightmare to pitch in. It was like the left-field fence at the Coliseum in Los Angeles, when the Dodgers first moved to L.A. and Wally Moon used to hit opposite-field pop-ups over it.”46 Another righty pitcher and longtime Islander, Dave Baldwin, confirmed that the Termite Palace was “a left-handed hitter’s dream.”47

The broadcaster for Belinsky’s no-hitter was 23-year-old Al Michaels, who later also compared Honolulu Stadium to Wrigley Field, Crosley Field, and Connie Mack Stadium. In his foreword to Honolulu Stadium, he said, “They’d been around for half a century and generations had grown up attending games there. They were part of the tapestry of so many lives. . .The Stadium then was a great, great place.”

Time was passing it by, though. Honolulu had already disclosed plans for a new stadium in February 1968.48 Michaels added, “It was a time when construction cranes were lined up like soldiers on the Waikiki skyline. And here was this old wooden structure right at the edge of things.” Ferd Borsch, who never missed an Islanders home game in 27 years as the club’s beat writer for the Honolulu Advertiser, described just how plentiful the termites were. “On hot and muggy nights, they would be out in the millions swarming around the stadium lights.”49 A long-running joke was that the termites were all holding hands, but if they ever stopped, the place would fall apart.

Another veteran Honolulu sportswriter, Bill Kwon of the Star-Bulletin, said, “When strong trade winds swept out of Manoa Valley, the whole place felt like it was going to topple over.” That 1999 column paid last respects to Fred Antone, the public address announcer who was the voice of Honolulu Stadium, perched “in a rickety three-seat aerie above the press box.” Kwon also talked about how driving rains could take the place of the usual Manoa mist.50 The playing field could get extremely muddy, as seen in particular during various Hula Bowls.

Another cultural icon of Hawaii was born in 1968: the TV show Hawaii Five-O. An episode that was filmed in 1969 and aired in January 1970 featured Honolulu Stadium in several sequences. A young Christopher Walken was one of the guest stars of “Run, Johnny, Run”, as was Al Michaels. Two of the show’s supporting actors – Herman Wedemeyer and Al Harrington – had once been big local football stars who played before capacity crowds at the stadium.

During their 15 years in the Termite Palace, the Islanders had their ups and downs (their overall record was slightly below .500). Their best regular season in that period came in 1970, when they were 98-48 under Chuck Tanner and drew 467,217 fans – best in the minors, almost three times that of any other PCL team, and the highest total in the league since 1950. Alas, the Islanders lost the playoff finals to the Spokane Dodgers, managed by Tommy Lasorda.

In their capsule history of the 1970 Islanders, historians Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright provided a quote from the team’s general manager, Jack Quinn, as the season was drawing to a close. Quinn told the Honolulu Advertiser, “I never thought we could play to so many fans in a 45-year-old wooden-frame stadium with only 200 parking stalls and very little street parking.” As Weiss and Wright noted, though, there was excellent public transportation. Several bus lines went to or very near the park.51

For those who did choose to drive, the lack of immediate parking options actually heightened the sense of community. Honolulu native Donna L. Ching remembered walking from her grandmother’s house on nearby Wilder Avenue to attend high-school football games. “Everyone was on foot from parking at their friends’ or on the street. That ‘parade’ to the stadium was part of the excitement!”52

September 1972 brought another round-robin baseball tournament to Honolulu Stadium – the Kodak World Baseball Classic. Five teams squared off: the Islanders, the champions of the three Class AAA leagues, and a group of Caribbean All-Stars. Attendance was very poor, though, despite the high talent level. This too turned out to be a one-off.53

Meanwhile, the Aloha Stadium project dragged on. One report in late 1970, when rumors of an NFL franchise for Honolulu were swirling, said that the stadium would be ready for the Hula Bowl in January 1972.54 After that target was missed, officials then hoped for a late 1973 opening, but assorted technical and legal difficulties continued. Sportswriters derided the replacement as a “monster” and “white elephant.”55 It was a parallel to what occurred in Montreal with another charming but outmoded little stadium, Jarry Park, and its hulking successor, Olympic Stadium. Both “The Big O” and Aloha were heralded as marvels of architecture – but construction ran way over time and budget, keeping the old places in use years longer than intended. Both were sterile and inconveniently located miles from downtown. Their vastness swallowed up crowds. They became decaying money pits, and calls for their replacement and/or demolition grew.

Finally, in August 1975, Aloha Stadium was ready to open. The Hawaiians of the WFL moved there after their game of August 23. The last sporting event in Honolulu Stadium took place that September 8. On that Monday night, the Hawaii Islanders won a PCL championship for the first time in their history. Before 7,731 delighted fans, the Islanders beat the Salt Lake City Gulls, 8-0, to win the series 4 games to 2. The Islanders repeated as PCL champs in 1976 after moving to Aloha Stadium, but won no more titles in their remaining 11 years as a franchise.

At the beginning of 1976, the State of Hawaii bought all the stock of Honolulu Stadium Ltd. Bids went out for demolition; meanwhile the Stadium stood abandoned. On September 5, 1976, the city of Honolulu staged a farewell party. The next day, the bulldozers moved in.56 Those with a belief in spirits may imagine that the place had a soul. Larry Price, a radio personality for KSSK-FM in Honolulu, said, “It creaked, actually creaked, like it was alive; (it was) kinda spooky.”57

A public space, Old Stadium Park, now occupies the area. A plaque commemorates the Termite Palace and the many great athletes who played there. Yet its memory lives on in other ways. Internet forums devoted to Hawaiiana frequently feature the memories of surviving fans. A one-hour television special – also called “Honolulu Stadium: Where Hawaii Played” – first aired on Honolulu Public Television in December 1996. Art Suehiro’s book was reissued in 2008.

Acknowledgments

Mahalo to Art Suehiro and Donna L. Ching for their support. Thanks also to George Sherrod, Mike Floyd, Don Ferrarese, Dan Tate, and Dave Baldwin.

Photo Credits

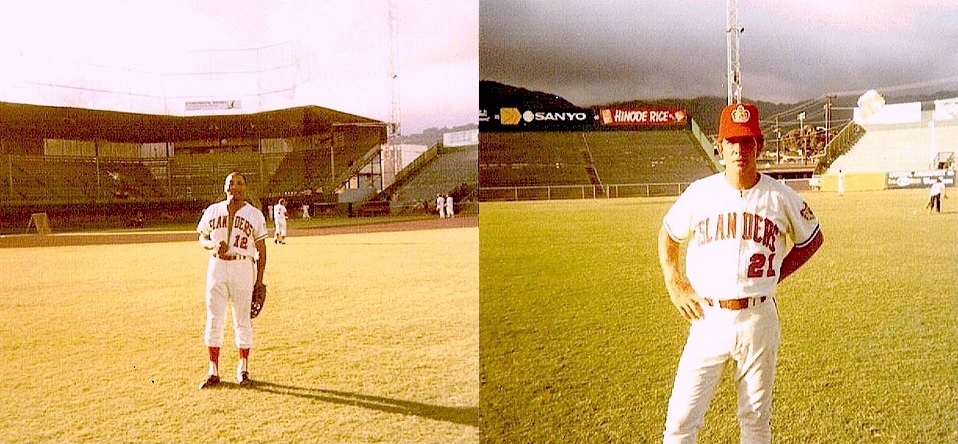

Leon “Daddy Wags” Wagner and Dennis Ribant at Honolulu Stadium, 1971 – courtesy of Mike Floyd (then playing for Salt Lake City).

Sources

Books

Arthur Suehiro, Honolulu Stadium: Where Hawaii Played, Honolulu, Hawaii: Watermark Publishing, 1995. Foreword by Al Michaels.

Television programs

“Honolulu Stadium: Where Hawaii Played”, produced and directed by Scott Culbertson, Hawaii Public Television, 1996.

Notes

1 Quoted figures ranged from 24,000 to 27,000.

2 Rod Ohira, “Fond thoughts of fine old things”, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, December 29, 1999.

3 John Clayton, “Hawaii: Baseball – A Stranger in Paradise”, Pittsburgh Press, July 10, 1983, D-2.

4 Nadine Kam, “Moˈiliˈili”, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, February 19, 2006. For an in-depth look at the Moiliili Quarry, which ceased operations in 1949, and its general importance to Honolulu, see Kelcey Ebisu, “From Stone Quarry to Athletic Complex: The Makai Campus (Acquired 1953), Chapter V of Building a Rainbow: A History of the Buildings and Grounds of the University of Hawaii’s Manoa Campus (Victor N. Kobayashi, editor), Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii at Manoa, 1983 (https://evols.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10524/650/23/bar11_chapter5.pdf).

5 E-mail (Facebook post) from Mike Floyd to Rory Costello, March 2, 2016.

6 “J. Ashman Beaven”, Hawaii Sports Hall of Fame website (http://www.hawaiisportshalloffame.com/wp/j-ashman-beaven/). George F. Nellist (editor), The Story of Hawaii and Its Biulders, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 1925. Tim Ryan, “Honolulu Stadium: Hawaii’s Field of Dreams”, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, November 25, 1996.

7 Rich Budnick, Hawaii’s Forgotten History, Honolulu, Hawaii: Aloha Press, 2005, 58.

8 Catherine E. Toth, “The History of Five Local Grinds”, Hawai’I Magazine, June 24, 2015.

9 John Clayton, “Hawaii: Baseball – A Stranger in Paradise”, Pittsburgh Press, July 10, 1983, D-2.

10 E-mail (Facebook post) from George Sherrod to Rory Costello, February 13, 2016.

11 E-mail (Facebook post) from Mike Floyd to Rory Costello, March 2, 2016.

12 Jonathan Fraser Light, The Cultural Encyclopedia of Baseball, Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Co., 2005, , 407.

13 “E Hoikeike Ana O Babe Ruth I Kana Kalena Maanei Nei (Babe Ruth Will Exhibit His Talents Here”, Ke Alakai o Hawaii, October 19, 1933, 4. (http://nupepa-hawaii.com/2015/12/06/babe-ruth-at-the-honolulu-stadium-1933/)

14 “Noha O Bebe [sic] Ruth E Paani I Elua Kemu Kinipopo Ma Honolulu Nei”, Ke Alakai O Hawaii, September 28, 1933, 3.

15 “Ruth Smacks Homer”, United Press, October 23, 1933.

16 Robert Fitts, Banzai Babe Ruth, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2013: 75.

17 Fitts, Banzai Babe Ruth, 75.

18 “NFL Exhibition Games Played at Neutral Sites”, FootballGeography.com, June 2, 2013 (http://www.footballgeography.com/nfl-exhibition-games-played-at-neutral-sites/)

19 “Hawaii Seen as Democratic Isle”, The Afro-American, October 14, 1946, 11.

20 Jack Durkin, “Down the Line”, Syracuse Herald-Journal, June 10, 1944.

21 Richard Ben Cramer, Joe DiMaggio: The Hero’s Life, New York, New York: Touchstone, 2001: 212. June Watanabe, “Where (___) used to be”, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, September 9, 1996.

22 E-mail (Facebook post) from Mike Floyd to Rory Costello, March 2, 2016.

23 William Cole, “Misery filled baseball star’s days in isles during WWII”, Honolulu Star-Advertiser, September 10, 2010.

24 “Urge Honolulu as Coast Loop Member”, United Press, February 28, 1945.

25 Bill Weiss and Marshall Wright, “Top 100 Teams – #38: 1970 Hawaii Islanders”, MiLB.com (http://www.milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=38)

26 “Seals Prepare”, United Press, March 19, 1947. The Giants won the first three; then the Seals took the final two. Associated Press, March 27, 1947.

27 E-mail from Dan Tate, President of the Don Ferrarese Charitable Foundation, to Rory Costello, February 15, 2016. Tate interviewed Ferrarese on February 15, 2016.

28 Jim McGee, “O’Doul Stars Have Rough Time in Air – and at Honolulu”, The Sporting News, October 24, 1951, 2.

29 Red McQueen, “Lopat Larrupers Give Power Show in Hawaii”, The Sporting News, October 22, 1952, 5. Red McQueen, “Lopat’s Stars Win 6 Games, Slice a Juicy Melon from Good-Will Jaunt to Hawaii”, The Sporting News, October 29, 1952, 13/.

30 “Short Takes from the Sports Wire“, Jamestown (New York) Post-Journal, October 13, 1953, 14. Sport Briefs”, Brooklyn Eagle, October 21, 1953, 18.

31 Red McQueen, “Lopat Stars Win 6 in Hawaii, but Draw Only Slim Crowds”, The Sporting News, October 27, 1954, 21.

32 “Yanks Drew 549,700 in 25 Games”, The Sporting News, December 7, 1955, 10.

33 Red McQueen, “Brooks Hailed Like Kings, Play Like Champs in Hawaii”, The Sporting News, October 24, 1956, 9.

34 Red McQueen, “Cardinals Pound Burdette and Turley Before Small Crowds in Hawaii, Games”, The Sporting News, October 22, 1958, 7/

35 “Elvis Presley in Hawaii: 1957 to 1977”, ElvisPresleyPhotos.com (http://elvispresleyphotos.com/elvis-hawaii.html). Elvis received his draft notice in December 1957 and served in the U.S. Army between March 1958 and March 1960.

36 “Hawaii Ending Big Celebration”, Associated Press, March 14, 1959. “Hawaii Ends Its Celebrating; Turns to Talking Politics”, Associated Press, March 14, 1959. A statehood plebiscite (which is still the subject of some controversy) still lay ahead, on July 27. On August 21, President Dwight Eisenhower signed the Hawaii Admission Act into law.

37 “Honolulu Gets Chance at Triple A Club, but Stadium Owner Is Out”, Associated Press, November 16, 1960.

38 “Honolulu Has Problems on Its Stadium”, Associated Press, December 23, 1960.

39 “Honolulu Officially Enters Coast Loop”, United Press International, January 12, 1961. “[Tommy] Heath Chosen as Manager for Honolulu”, Associated Press, January 12, 1961.

40 Vincent F. Stanich, “Sacramento Solons enter by old exit”, Sacramento Union, April 7, 1974.

41 “O’Doul Scout for Hawaii”, Associated Press, February 5, 1961.

42 “Hawaii Has Old, Small ‘Junk-Baller”, United Press International, June 18, 1961. Findagrave.com shows Mancao’s tombstone, with a birthdate of December 5, 1914.

43 Randy Miller, Harry the K, Philadelphia: Running Press (2010): 61.

44 “Amateur Baseball Tourney Is Scheduled for Honolulu”, Associated Press, June 21, 1966. Alden Cross, “Amateur Baseball Takes Big Stride”, Spokane Spokesman-Review, September 18, 1966, 8.

45 “Dodgers Find Home Plate!”, Associated Press, October 17, 1966.

46 E-mail (Facebook post) from George Sherrod to Rory Costello, February 13, 2016.

47 E-mail (Facebook post) from Dave Baldwin to Rory Costello, March 3, 2016. Honolulu Stadium was especially tough for Baldwin; as is typical of a righty side-arm/submarine hurler, he was less effective against lefties. It was his home stadium for two full seasons (1971 and 1972) and parts of three others (1965, 1966, and 1974).

48 “Honolulu Plans New Stadium”, United Press International, February 18, 1968.

49 “Longtime Advertiser baseball writer, Ferd Borsch, dies”, Honolulu Advertiser, June 25, 2006.

50 Bill Kwon, “Antone was often heard, never seen”, Honolulu Star-Bulletin, July 28, 1999.

51 Weiss and Wright, “Top 100 Teams – #38: 1970 Hawaii Islanders”

52 E-mail from Donna L. Ching to Rory Costello, February 9, 2016.

53 Joe Marcin, “World Baseball Classic a Financial Fizzle”, Sporting News Baseball Guide, 1973.

54 Marty Ralbovsky, “Rain, Mud Cool Off Hawaii as Hot Sports Area”, Newspaper Enterprise Association, December 19, 1970.

55 “Aloha Arena Built”, Associated Press, August 13, 1975.

56 The job was finished on October 4, 1976, according to Budnick, Hawaii’s Forgotten History, 58.

57 Ryan, “Honolulu Stadium: Hawaii’s Field of Dreams”