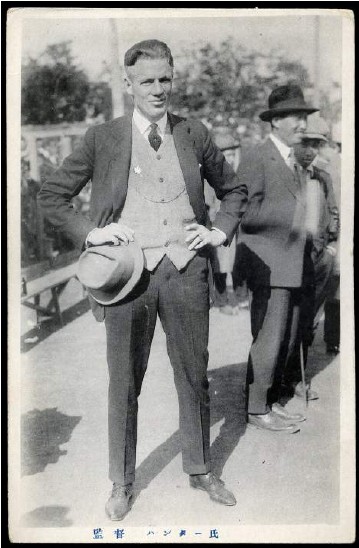

Herb Hunter

With a major-league career that comprised only 39 games, Herbert Harrison Hunter still managed to play in baseball’s four biggest markets: New York, Chicago, Boston, and St. Louis.

With a major-league career that comprised only 39 games, Herbert Harrison Hunter still managed to play in baseball’s four biggest markets: New York, Chicago, Boston, and St. Louis.

After 1920, in which he played in four games for the Boston Red Sox, Hunter became a baseball tour impresario of sorts, leading a group of major leaguers to play baseball in Japan, eventually becoming known as Baseball’s Ambassador to the Orient and leading numerous tours to the Land of the Rising Sun.

One of the few Red Sox players actually born in the city of Boston — on Christmas Day, no less, in 1895 — Hunter played all four infield positions and the outfield as well. He hit left-handed and threw right-handed. He had a listed playing weight of 165 pounds and stood a half-inch over 6 feet tall.

He was born in the East Boston section of the city to Robert Hunter, a Scottish immigrant (1880), and Robert’s wife, Fannie Thompson Hunter, a Nova Scotian whose parents both came from Ireland. Herb was the seventh of the couple’s eight children: George, Lizzie (Elizabeth), William, Frances, Robert, Joseph, Herbert, and Edith. Fannie was busy enough with work at home to not seek an outside job. Robert was a blacksmith. The family lived in Somerville, Massachusetts, at the time of the 1900 Census, but by 1910 was in Melrose, New Jersey, where Herb graduated from high school. By 1920 those who were still living with their parents made their home in Highlands, New Jersey. Among the occupations the children had were electrician, drugstore clerk, milliner, stenographer, and professional ballplayer.

Herb Hunter later became much more than a ballplayer. His start was a modest one. In the summer of 1913, he played ball with Bethlehem, New Hampshire, in the White Mountain League. He played for the Melrose and the Atlantic Highlands high school teams, and two other Garden State teams – the Highland Stars of Red Bank and the Long Branch team. Charlie Herzog of the Cincinnati Reds gave Hunter a tryout, in Boston at the Braves’ South End Grounds, on June 9. He was said to have had an offer from a Canadian League team for the summer of 1914.1

Hunter wound up playing in the Class C Colonial League in 1914, as an outfielder and first baseman for the Brockton Shoemakers. He played in 33 games but was one of the worst hitters in the league (ranking 85 out of 91 players), batting just .171. Hunter somehow wound up at the Linsley Military Institute in Wheeling, West Virginia, in 1915, preparing to go to West Point. He graduated on June 1, but had already attracted visits from more than one major-league scout. He’d hit superbly for the school team, batting .572, fielded well (.993), was fleet afoot, and could play first base and any of the three outfield positions. He played some in the Central League for the Wheeling Stogies, and manager Pop Schriver was said to have offered him a deal, but Hunter had been notified that a contract was in the mail from the New York Giants.2

When the Giants signed Hunter, Frank Wessell got a check for $200 for the tip. Wessell was a former shortstop for the Stogies who kept his eye on players. He wrote Giants manager John McGraw that he had “dug up one of the most natural hitters” he had ever seen in action. Wessell was promised another $300 if Hunter “made good.”3

In June the Los Angeles Times noted Hunter as one of four “college stars” signed by McGraw the previous week.4 He was to join the Giants in Pittsburgh before the end of the month. He actually played in an exhibition game, at third base, against the Long Branch (New Jersey) Cubans in Long Branch on July 2, 1915, batting seventh and going 2-for-4 with a double. That was Hunter’s only game with the team until the following spring, when he did exceptionally well and seemed to be set to start at third base until he suffered several minor injuries, including a spiking. McGraw is said to have hoped to place Hunter with an American Association or International League team, but the other major-league clubs refused to waive on him. He was seen as a potential prize but really had played very little ball.

At spring training of 1916 in Marlin, Texas, Herb trained as a first baseman. His debut came on April 29, 1916. The Giants lost the game, 5-4, to the Dodgers in the 12th inning. It was their seventh loss in a row, one of the worst starts in franchise history at 1-8. Hunter pinch-hit in the bottom of the 12th for pitcher Fred Anderson but unsuccessfully. He got his first start, at third base, on May 1 – and his first hit, a single in the seventh – but the Dodgers prevailed again and the Giants were 1-9. “He did his part well enough” at third base, wrote the New York Times.5 Hunter appeared in 21 games, getting 28 at-bats and seven hits – all singles except for one home run. The homer turned out to be the only extra-base hit of his entire career. It came on August 25, off Pittsburgh’s Bob Harmon in the top of the 11th inning, a three-run homer to deep center. Hunter had come into the game when the shortstop was ejected; the third baseman slid over to short and in went Herb at the hot corner. One might think that his hit was the game-winner, but it was not. That had scored when the batter before him singled in the go-ahead run. The final score was 6-2.

Three days later, Hunter was traded to the Cubs, along with second baseman Larry Doyle and outfielder Merwin Jacobson, to obtain infielder Heinie Zimmerman. Hunter had hit .250 for New York in his 28 at-bats, and was deemed by the New York World as “a player of great promise.”6 He was hitless for the Cubs in four at-bats. He didn’t draw his first base on balls until four years later. In 1917 he was back with the Cubs again, after an eventful spring training. When the Cubs passed through El Paso, they had a six-hour stopover. Hunter managed to get arrested for gambling at keno, handcuffed and taken to the judge – apparently a setup – but Herb struggled with the city marshal and stole his gun, then seized the sheriff and forced him to go to the next stop on the line as the Cubs’ train pulled out of town. It was all in good fun, but pushing the envelope.7 On the 23rd itself, a dozen or so players including Hunter took the mule ride to the bottom of the Grand Canyon.8

When the season began in earnest, Herb again was hitless, this time in just three at-bats in three games. In July he was sold to the Vernon Tigers of the Pacific Coast League and he spent most of the year in the PCL with Vernon and then, after only a very short while with the Tigers, with the San Francisco Seals. He hit a combined .248. For the next two seasons, 1918 and 1919, he played for the Seals, batting .293 as a shortstop in 1918 and .263 as an outfielder in 1919. Sometime in late 1919, he seems to have entered the Navy, though he wasn’t there that long. It may have been one of the impulsive moves that earned him a reputation as a bit of an eccentric young man. The Boston Globe said it was understood he’d purchased his release from the Seals “but this is not vouched for.”9

As to the matter of Hunter’s eccentricities, at least one story said he was “the butt of almost every clubhouse joke.” Rob Fitts wrote in his book Banzai Babe Ruth: “Although friendly, with a charming smile, the young man was so absentminded that his manager would escort him to the railroad station to ensure that he would not miss the team’s road trips. Once in a tie game with bases loaded and one out, Hunter caught a fly ball in center field, stuffed it into his back pocket, and jogged to the dugout.”10

Then, in 1920, Hunter was with the Red Sox. Though he played in the outfield for Boston, one couldn’t really say his role was to take Babe Ruth’s place. He played his first three games in left, and the fourth and last one in center. He was a utility player, and not utilized that much at all. He did get a base hit, a single, on May 10 at Fenway Park. He scored, too, one of two runs scored that season. His final game with the Red Sox was on May 21. He finished 1-for-12 (.083). The Red Sox sent him to Indianapolis but he was “turned back” by them after a controversy. The Sporting News explained, “Hunter recently alleged that Boston tried to force him to sign a new contract at a lower salary so he could be sent to a minor club, and threatened to take his case to the National Commission, whereupon Boston released him.”11

Hunter then signed with the Little Rock Travelers, where he hit an undistinguished .220 in 39 games. In 1921, he was back in the major leagues with the St. Louis Cardinals but played in only nine games and then only sparingly – he had only three plate appearances all year long. He didn’t have a lot to show for his work – once more he batted .000, though he did walk once. Bizarrely, he was caught stealing three times, so even as a pinch-runner he didn’t perform. The three chances he got at first base in one game were all handled cleanly, though.

That winter Hunter took a position coaching the baseball teams at Waseda and Keio Universities in Japan, a result of his meeting some Japanese ballplayers while in San Francisco, and keeping in touch. A photograph in The Sporting News shows him arm in arm with captain Takasu of the Keio team. The photo was sent to the paper by M. Nishito of the Mariya Sporting Goods Company of Osaka. The accompanying letter was said to have been “full of praise of his work as a coach and of his qualities as a gentleman and true American citizen.”12

A later report said that Hunter rated Waseda shortstop Teddy Kubota as the best shortstop he’d ever seen.13 Hunter was invited to select a group of prominent major-league ballplayers and return after the 1922 season, bringing them to Japan to play both at Waseda and at Keio, and later to Korea.

There had apparently been some less-than-satisfactory behavior on the part of a tour led by another promoter that had played ball in Japan in 1920. Hunter had been on that tour, but was not involved in the controversy. The Sporting News editorialized that baseball looked as though it could become the national game in Japan, and that Hunter’s experience coaching there qualified him to lead a tour later in 1922, adding that the paper “hoped that he will exercise nice discrimination in his selection of players in order that his team may set our Japanese friends a higher example in manners and morals than had heretofore been the case. It is important that the Japanese should see America’s national game portrayed by professional players of high-class not only in skill but in conduct.”14 The paper had been impressed with the two ancient swords Hunter had been presented by the students he had coached.

On June 2, noting that American League president Ban Johnson had given the tour his blessing, the paper felt this was good because it allowed for some further supervision over the choice and conduct of the players, though it added, “The general impression of Herb Hunter is that he is a high class gentleman, capable of conducting such a tour as he proposes and the affair may be safe enough in his hands.”15 Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis gave his approval, though assigning umpire George Moriarty to oversee the deportment of the players.

The Cardinals released Hunter, and in 1922 he played second base for Little Rock again, batting .301 in 133 at-bats. He even pitched one game, too, but he lost it.

It didn’t appear that Herb Hunter had much of a future in baseball as a player, but he began to fashion a new life as an “ambassador of baseball.” The team he selected for the trip to Japan was the first one to truly be billed as an all-star tour. The group left the United States on October 19 on the ocean liner Empress of Canada and played its first of 17 games at Waseda. After some games in Japan, the players traveled to Seoul, where they played before 20,000 Korean spectators, and then on to Peking (Beijing) in China. Among the ballplayers on the tour were Casey Stengel, Waite Hoyt, Herb Pennock, Bullet Joe Bush, Bibb Falk, George “High Pockets” Kelly, Luke Sewell, and Irish Meusel. On the way back, the group stopped for Christmas in Manila and later played ball in Honolulu. It was a successful tour, planned to become an annual event, but the great September 1, 1923, earthquake in Tokyo forced cancellation of future plans. Hunter had hurt his arm badly in Korea, sufficiently that there was no hope he could continue to play high-level competitive baseball.

There was one sour note in the aftermath – the suggestion that the Americans hadn’t taken one early game seriously enough and allowed the Mita club to beat them. The loss was upsetting to Landis, as was the fact that the US players had treated the game as a “lark and a burlesque.” In not taking the Japanese team seriously enough, the Americans humiliated them to some degree, understandably provoking some negative comment from some Japanese sports editors, who also alleged that the loss to a Japanese team was a deliberate one calculated to stimulate ticket sales in later stops on the tour.16 Many of the players had traveled with their wives and at least 16 players came back with Japanese “chow pups”; Hunter himself had bought a “noodle hound” the year before. When the dog came back, it refused to eat American food and Hunter had to bring it special local food to eat. Because he wasn’t allowed to bring it on the streetcar, he also had taken it back and forth to the ballpark in a taxi.17

In May 1926, a group of Japanese university ballplayers (including two whom Hunter had coached at Waseda) came to Atlantic Highlands in New Jersey to play the local town team, which Hunter managed. That year he’d become owner of the Atlantic Highlands Coal Company, which he ran at least through 1933 and perhaps longer. He was able to play some local ball, and devoted time to managing and promoting the town teams. Another Waseda team came to play the Highlanders on May 26, 1927, beating them 5-4 before heading on to games against Yale and New York University.

The next tour to Japan was a two-month trip after the 1931 season. Hunter had in the meantime continued to travel to Japan as a coach and to build on the contacts and friendships he had forged. In 1928, he was able to take Ty Cobb, Bob Shawkey, and Fred Hofmann with him. In all, he reportedly traveled to Japan eight times in the 1920s. The 1931 trip was something of a co-production of Hunter and New York sportswriter Fred Lieb, sanctioned by Landis, thus exempting the players from punishment for postseason exhibition games. There is a back story to the involvement of Lieb that had Landis refusing to endorse Hunter’s involvement without the intercession of Lieb, with whom Hunter agreed to share profits. Rob Fitts details this and the story of the tour in his manuscript, as he does the transition from Hunter to O’Doul that would occur before the 1934 tour. (Fitts also mentions the discordant note of Hunter being arrested for stealing $20,000 worth of jewels from a woman in Queens, New York. The charges were dismissed but his good name was tarnished.)18

In April, a group of wealthy Japanese determined to establish Japan’s first professional baseball league, an eight-team circuit, and the New York Times said that Hunter had been offered a three-year contract to serve as an adviser to the group.19 After their travels, Lieb wrote a lengthy piece in The Sporting News which claimed that more youngsters in Japan were playing baseball than were in the United States.20 The 1931 tour included Lou Gehrig, Lefty Grove, Lefty O’Doul, Rabbit Maranville, Mickey Cochrane, Frankie Frisch, Al Simmons, and others. They played before as many as a half a million fans. Hunter was the guest of such political figures as the foreign minister of Japan, Count Yasuya Uchida, and the vice minister of foreign affairs, Mamoru Shigemitsu. The New York Times featured a large photo of the ballplayers and “baseball ambassador” Hunter, arriving in San Francisco after the tour. Lou Gehrig’s post-tour comments were reported at length two days later.21

Hunter’s Japanese contacts really wanted him to bring Babe Ruth over, and it took years. A note in the New York Times said that Ruth’s personal manager, Christy Walsh, and Hunter had been negotiating for some time to try to bring Ruth to the Pacific.22 In early 1934, The Sporting News wrote that Lefty O’Doul was going to take over the baseball touring business from Hunter, and was bringing two Japanese teams to tour in California during the summer of 1934.23

In 1935, the “commuting sports envoy to Japan” said that he would take a team of American football stars to Japan, selected and coached by Princeton’s Fritz Crisler. Hunter seemed to serve as a broker for a number of arrangements, such as Beans Reardon’s being invited to umpire a series of 12 games in Japan with a touring group of American amateur baseball champions.24

Rising tensions, and ultimately, war prevented future trips. One 1940 article said Hunter “is now distributing those little bat pencils.”25 Perhaps this was bigger business than it might sound, but it could have been a real comedown from ambassadorial works to hawking souvenir pencils.

Was Hunter Tokyo-bound again in 1943? So said The Sporting News. He had rejoined the United States Navy and was a chief specialist, “looking forward to his next journey there [Japan] with a far different purpose.” He was stationed at the Norfolk Naval Training Station in Virginia, awaiting orders. He’d seen “plenty of military activity” on his earlier trips, but “it was the last thought in my mind that they would be stupid enough to attack us.” 26

Hunter became involved in a number of other ventures. He was part-owner of the ball club in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, and also served as an umpire in at least three leagues: the Middle Atlantic League, the Mountain States League, and the Southeastern League, according to his Sporting News obituary.

Hunter died July 25, 1970, in the Florida Sanitarium and Hospital in Orlando, Florida, of respiratory failure due to chronic obstructive lung disease. At the time he was living in Maitland, Florida, and managing a hotel in the area, though experiencing some senile dementia, according to his death certificate. He was widowed, according to the information provided by his daughter (perhaps named after the military institute he’d attended), Lindsley Hunter Smith.

Sources

Thanks to Rob Fitts for sharing a considerable amount of material from his book Banzai Babe Ruth: Baseball Diplomacy and Fanaticism in Imperial Japan, published by the University of Nebraska Press circa in 2012. In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed the online SABR Encyclopedia, Retrosheet.org, and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 Red Bank Register, June 10, 1914.

2 Unidentified June 12, 1915, clipping in Hunter’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

3 Undated, unidentified clipping in Hunter’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library.

4 Los Angeles Times, June 23, 1915.

5 New York Times, May 2, 1916.

6 New York World, August 29, 1916.

7 A full account appears in the Chicago Tribune on February 23, 1917.

8 Chicago Tribune, February 24, 1917.

9 Boston Globe, April 21, 1920.

10 Robert K. Fitts, Banzai Babe Ruth: Baseball, Espionage & Assassination During the 1934 Tour of Japan (Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2012): 8.

11 The Sporting News, August 12, 1920.

12 The Sporting News, February 16, 1922.

13 The Sporting News, March 30, 1922.

14 The Sporting News, May 4, 1922.

15 The Sporting News, June 2, 1922.

16 The Sporting News, November 2, 1922.

17 The Sporting News, February 1, 1923.

18 Fitts, 28.

19 New York Times, March 28, 1931.

20 The Sporting News, January 7, 1932.

21 New York Times, December 21 and 23, 1931.

22 New York Times, September 28, 1933.

23 The Sporting News, April 26, 1934.

24 Christian Science Monitor, October 11, 1935. The football story was in the March 1, 1935, New York Times. An August 12, 1937, article in the Hartford Courant said that Hunter’s next trip would be his 16th to Japan.

25 Atlanta Constitution, December 7, 1940.

26 The Sporting News, June 15, 1943.

Full Name

Herbert Harrison Hunter

Born

December 25, 1895 at Boston, MA (USA)

Died

July 25, 1970 at Orlando, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.