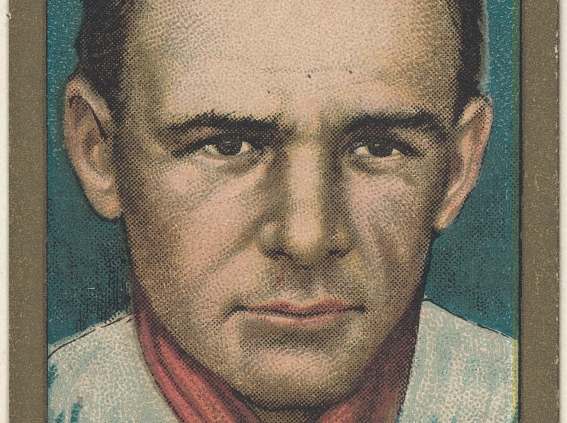

Bob Harmon

Saturday Night Live’s Garrett Morris popularized the line “Béisbol has been berry, berry good to me.” Long before that sketch, pitcher Bob Harmon was living proof of what a baseball career could do for the life of a player. He carefully managed his paychecks and invested in oil fields while still pitching for the St. Louis Cardinals and Pittsburgh Pirates during the Deadball Era. In 1922 he liquidated much of his petroleum holdings and purchased nearly 800 acres of prime farmland near Monroe, Louisiana.1 He became an affluent, influential agriculturalist gaining prominence in his area and statewide. Never losing his love of the game, Harmon was often identified in the local paper as “Monroe’s biggest baseball enthusiast.”2 Yes, the game of baseball was indeed “berry, berry good” for Bob Harmon.

Saturday Night Live’s Garrett Morris popularized the line “Béisbol has been berry, berry good to me.” Long before that sketch, pitcher Bob Harmon was living proof of what a baseball career could do for the life of a player. He carefully managed his paychecks and invested in oil fields while still pitching for the St. Louis Cardinals and Pittsburgh Pirates during the Deadball Era. In 1922 he liquidated much of his petroleum holdings and purchased nearly 800 acres of prime farmland near Monroe, Louisiana.1 He became an affluent, influential agriculturalist gaining prominence in his area and statewide. Never losing his love of the game, Harmon was often identified in the local paper as “Monroe’s biggest baseball enthusiast.”2 Yes, the game of baseball was indeed “berry, berry good” for Bob Harmon.

He was born Robert Greene to Frank and Cora (Noyes) Greene on October 15, 1887, in Liberal, Barton County, Missouri, where the Noyes family were farmers.3 His father was a political activist and organizer for the Knights of Labor; his mother was a schoolteacher.4 The day after his birth, his mother died. His father’s work required a lot of traveling, so Robert was adopted by his mother’s sister Viola and her husband, Orrin Harmon, who lived in Washington state at the time. (His obituary would claim, erroneously, that he was a native of Washington “where he was reared by an uncle.”5)

After the death of the Harmons’ son Herschel in 1896, the family returned to Barton County, where Robert received the bulk of his schooling. His upbringing was no doubt quite different from that of other Missouri children because the town of Liberal had been founded as an atheist utopia by Civil War veteran George Walser. It was described as a town without a “church, saloon, God, or hell.”6 But it did have a town baseball team, and by the time he was 18 Bob was the leadoff batter playing shortstop and the outfield when he wasn’t pitching.

In 1907 Harmon left Liberal and headed west to the copper mines of eastern Arizona. In his two years there, he grew to be six feet tall and weigh 187 pounds.7 As a right-handed pitcher, he developed a powerful fastball that was supplemented by a slow curveball. He first appears in box scores out west playing for the town of Clifton, Arizona, in a series played in El Paso, Texas. A switch hitter, he also played first and the outfield.8

In 1909 manager Dale Gear of the Shreveport (LA) Pirates recruited Harmon to play in the Class C Texas League. Harmon’s first appearance came against the Chicago Cubs on March 20. He tossed four scoreless innings before being relieved just as Chicago “was working into a gait that would have broken Harmon’s spell.” The Cubs won, 5-1.9

Harmon continued to shine in the pre-season but opened the league campaign with a loss to Dallas that was followed by other unspectacular outings. A local paper on May 9 showed him with a 1-2 record, a fielding percentage of .800, and a batting average of .300.10 Gear decided to send Harmon to Fort Smith in the Class D Arkansas State League. The hope was that a demotion would help Harmon who had been “lacking in nerve and confidence.”11

Though faced with an imminent demotion, Harmon was sent to the hill against Galveston on May 10 and threw a wrench into Gear’s plans by authoring a no-hitter against the Sand Crabs. He struck out eight with just one base runner reaching on an error in the 6-0 win. The assignment to Fort Smith was quickly rescinded.12

Gear began using Harmon more and was rewarded with four wins including a two-hit shutout of Oklahoma City. Nevertheless, rumors persisted that he wanted to send him elsewhere. In mid-June he sold Harmon to the St. Louis Cardinals for a reported $2,500.13 14 Shreveport fans were disappointed to see the 21-year-old Harmon leave. One female fan echoed the sentiments of many when she said, “I don’t see why we should try to get good players if we must sell or give them away as soon as they make good.”15

Harmon joined the Cardinals and manager Roger Bresnahan in St. Louis. He was given his baptism on June 23 when he pitched the final frame in a loss to the Pirates. He made his first start the next day and was plagued by wildness, walking the first two batters. Despite “ragging” from Honus Wagner and other Pirates, he settled down. In the third Chappie Charles singled and Harmon walked. The two men rode home on Bobby Byrne’s triple to give St. Louis the lead, 2-0. In the sixth, Wagner coaxed a lead-off walk, a single and double followed and when the inning ended the Pirates had gone ahead, 3-2. He was pulled in the eighth and took the loss.16

Harmon earned his first major-league win on July 14 in Philadelphia. In a “gritty” performance he went 11 innings for a 6-4 win. At the plate he added two hits and an RBI.17 He followed that with a 16-inning complete game 4-3 win in New York. He had walked seven in each of the wins but knuckled down in the clutch. He closed out his rookie season with two streaks — an eight-loss stretch in late August/early September, and three wins to close out the year.

The following year Harmon led the team in innings pitched (236) and the league in walks (133) and wild pitches (12). He posted a 13-15 mark for the seventh-place Cardinals. Bresnahan worked him as much as possible, including nine starts in July. He closed out the year with five wins and two saves (by today’s standards) in September.

Over the winter Bresnahan and the Cardinals front office decided to completely rebuild their mound staff. Harmon would have been gone too, but Bresnahan could not get the quality he expected for him.18 Bresnahan’s foresight (and the development of Harmon and Slim Sallee) paid dividends as the Cardinals posted a winning record in 1911, the first time they had topped .500 since 1901. Harmon had a career year, winning 23 games to finish fourth in the league behind three future Hall of Fame hurlers. He led the league in starts (41) and walks (181) while finishing behind Pete Alexander in innings pitched with 348. On May 9 he tossed a three-hit shutout at Brooklyn, starting a streak that saw him win seven consecutive complete games. He closed out the season in superb form by throwing a two-hit shutout in Cincinnati. In the post-season match up with the Browns he posted a .444 batting average and won the 100-yard dash contest but was the loser in the final game.19 He returned to Liberal that fall and purchased some land, probably his first foray into real estate.20

Harmon opened the 1912 season with a four-hit 7-0 win over the Pirates before 20,000 fans at Robison Field winning. The Cubs found him very hittable in his next outing, accepting seven walks and pounding out 11 hits to end the Cardinals’ three-game win streak, 9-2. The two games were indicative of what Harmon’s season would be like. He could be lights out in one start and then show poor control and be an easy mark in another.

Harmon possessed an excellent fastball with a “hop” that veteran catcher Heinie Peitz described as having “a nasty twist… as it shoots across the plate,”21 but Bob had become infatuated with his slow curve. On June 1, facing the Giants in relief, he offered up the slow curve to Josh Devore (who hit 11 home runs in a career of 601 games) and watched as it sailed into the right field stands. St. Louis sportswriter W. J. O’Connor blasted Harmon who “has deluded himself with the idea that the curve ball is as effective as his fast one.” [Teammates] “say that his curve ball is bonbons for the batters, but Bob refuses to change.”22

Harmon’s roller-coaster season continued into July when he lost to the Cubs on July 5, 4-0. His record stood at 7-13 for the Cardinals, who were in seventh place and playing below .400 ball. Then he captured six consecutive victories including two shutouts.

Featuring speed on the diamond brought Harmon the winning streak, but when he showed speed on the streets of St. Louis, he found himself in trouble. One of just four Cardinals players who owned a car, he was arrested by a motorcycle patrolman for racing a local salesman. The officer claimed the two men “exceeded thirty-five miles an hour.” Harmon admitted he was “going some” in his Buick.23The two men were fined $5 each but it was reduced to $3. (They were fortunate because later that day the same judge found a man guilty of disturbing the peace by cursing at his wife. Despite the man’s claim that his wife was used to the swearing he was fined $10.)24

Harmon closed out the year with an 18-18 record. He opened the first game of the post-season series with the Browns and “was about as bad as any pitcher could be” and remain in the majors. He surrendered seven hits, walked eight and left the game down, 6-3. The Cardinals rallied to win, 7-6, in 10 innings.25 He followed that performance by surrendering 10 hits in a 4-0 loss.26 He added a third loss in the series, which was won by the Cardinals, 4-3-1.27

Harmon was a terrific violin player. Some called him a fiddler while others said the style was rag-time, but he had talent and never failed to take the violin on road trips. In December he struck a deal to appear for 10 weeks in vaudeville shows that played the theatres on the north side of St. Louis.28

In 1913 the Cardinals’ ownership parted ways with Bresnahan and made second baseman Miller Huggins manager. The pitching staff added 21-year-old pitcher, Poll Perritt. In the ensuing years Perritt would encourage his teammates to invest in the Louisiana oil fields. Harmon bought an interest as did outfielder Rebel Oakes. The trio would all profit handsomely from their wise speculation.

On the baseball fields, fortunes were a far different matter. Harmon balked at the contract offer from the team. After a brief unsuccessful holdout, Harmon made his first start in the seventh game of the year, a 5-4 loss to the Pirates. Huggins used him as both a starter and reliever for most of the year; he finished 8-21 for the last-place Cards.

Despite the dismal record for a losing ballclub, Harmon could be assured of fan support. Early in his career Harmon had met Beulah Mysonheimer, who became of fan of his pitching style. A serious relationship developed and on October 11, 1913, they were wed at St. Paul’s Methodist Church in St. Louis.29 On December 12, word came that Harmon had been traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates as part of an eight-player deal.

The trade news arrived shortly after Harmon had returned to St. Louis from a trip to the Shreveport area. He had enjoyed his season in Louisiana and when an opportunity to buy property there arose, he jumped at the chance. In St. Louis he had an interest in a wallpaper business and a pool parlor. He traded those ventures for a cotton plantation in a sale that was aided by Rebel Oakes.30

According to Harmon biographer Richard Cooper, the nickname of “Hickory Bob” came about because Harmon loved to go camping in the Ozark Mountains and he felled many a hickory tree to fuel his campfires.31 The name began to appear in the St. Louis papers in 1912 and became commonplace in his days with Pittsburgh and during his retirement.

Harmon cut his walks to 55 in 30 starts and posted a 13-17 record for the 1914 Pirates. Manager Fred Clarke liked his durability and in 1915 Bob led the team in starts and innings pitched while twirling a career-high five shutouts. By modern Sabrmetrics his ERA+ was the best of his career at 108. The following year Jimmy (Nixie) Callahan took over as manager. Al Mamaux became the staff leader and Harmon found himself relieving (14) almost as often as starting (17). His eight wins were third highest for the sixth-place team.

Harmon and his wife set up housekeeping near Homer, Louisiana. The Pirates sold his contract to Columbus in February. Harmon balked at the demotion and manager Joe Tinker of Columbus paid him a visit to discuss the future. Harmon told Tinker the “farm requires so much attention” that leaving the game was the right choice. Harmon suggested that a good crop of onions and potatoes could earn him as much money as a season in the minors.32

Farming agreed with Harmon and over the years he would become an outspoken leader for the farm community, but baseball still had its lure. He and Callahan had not gotten along, but Callahan had been replaced midway in 1917 and Hugo Bezdek was now the Pirates manager. Because Harmon had refused to go to Columbus, his rights had reverted back to Pittsburgh.

Over the winter, Harmon traveled to Baton Rouge and worked out with the Louisiana State team. He had always taken care of himself and the farming lifestyle only enhanced his conditioning. When the Pirates sent a contract, he affixed a signature and committed to another season.33 He was used in a dual capacity the first two months of the season. In June he was given six starts in which he surrendered a mere 16 runs (seven of them on June 28) but he could only earn one victory.

After a shelling on June 28 by St. Louis, Harmon asked for and was granted a leave of absence by Bezdek and team president Barney Dreyfuss. He wanted to go back to Louisiana and supervise the crop harvest on his properties.34 He ended the season at 2-7, giving him a lifetime 107-133 record. The Pirates continued to carry him on their reserved list until March 1923.35

Harmon had grown up in a farming family and knew what the occupation required. He was fortunate enough to have the finances to weather the ups and downs. In 1922 he purchased the Roselawn Plantation near Monroe, Louisiana, and made it his primary residence.36 With the purchase, he took over the successful Roselawn Dairy. When the Depression tightened in the Monroe area, he spearheaded the drive to form a dairyman’s cooperative that would eventually operate its own processing and bottling facilities.37

Like any farmer, Harmon endured hardships and successes. The local newspaper chronicled successes like huge turnips weighing as much as nine pounds and the addition of cucumbers as a fall crop. His tough times included a flood in 1927 and an early-morning twister in 1950.

A gregarious, personable fellow, Harmon became prominent in the state and even on the national level in farm and soil conservation circles. His hard work in the 1920s and into the Depression paid off because he became something of a gentleman farmer. The 1940 census listed him as working only 20 hours a week. He took vacations each year, often visiting sites in the “Old West.” One of his more extensive trips came in 1956 when he and a friend drove through historic sites in Texas, visited the Grand Canyon, the Navaho reservation, Phoenix, and Northern Mexico.38

Harmon never totally left baseball. He played with and managed the Homer team when he first took residence there. Rebel Oakes joined him on the team. In 1924 he was the temporary manager of the Monroe team in the Class D Cotton States League.39 He guided the players through their preseason preparations before giving way to Bill Wise. In 1930-31 he served as an umpire in the Cotton States League. Little League came to Monroe in 1951 and while Harmon was not one of the founders or officers, he made it a point to support the cause. The local papers gushed over the hot cakes and sausage fund raiser he championed in 1952.40

Bob and Beulah adopted a daughter, Jean Brooks Harmon, in 1926. He was burned badly in a farming accident in 1946 which contributed to the Harmons’ downsizing in the 1950s. They eventually sold off all but 50 acres of the plantation. In the 1970s Jean turned the plantation house into a restaurant that she managed.

Harmon was a Mason, Odd Fellow, and belonged to the El Karubah Shrine in Shreveport.41 He served on numerous farming boards, soil conservation committees, and bank associations. He told a reporter that he liked playing ball and working the oil business but as a farmer “I’m finding real happiness and genuine satisfaction.”42 He died suddenly in the Monroe hospital on the evening of November 27, 1961, survived by Beulah, Jean, and three grandchildren. Harmon was laid to rest in the Riverview Burial Park in Monroe.

The subtitle of Richard Cooper’s book neatly condensed and defined Harmon’s story. Cooper penned, “From Missouri orphan to the Major Leagues to Louisiana millionaire, Bob Harmon touched all the bases. The true story of a dead ball era star.”

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by William Lamb and Norman Macht. It was fact checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Baseball Reference and Retrosheet was used for game details. Ancestry.com provided census/family information. Thank you to Pauletta Orahood at the Barton County Historical Society. She provided the details of Harmon’s days with Liberal baseball and Richard Cooper’s biography of “Hickory Bob.”

Notes

1 “Ouachita Farm Life Satisfies Baseball Star,” Monroe (Louisiana) News-Star, August 20, 1925: 2.

2 “Jes’ Ramblin’,” Monroe Morning World, February 17, 1952: 10.

3 In 1960 Harmon submitted the questionnaire for the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown showing the ‘e’ on Greene.

4 “Free Lecture,” Canton (Kansas) Carrier, October 21, 1886: 3.

5 Paul Martin, “Big Leaguer Harmon Dies; Funeral Set,” News-Star, November 28, 1961: 1. Biographer Cooper credits him with about eight years of schooling in Liberal.

6 Steve Everly, “Strange Liberal, from infidelity to faith,” Springfield (Missouri) News-Leader, December 30, 2001: 15.

7 The 187 pounds comes from Harmon’s HOF questionnaire. In 1912 his weight was listed as 195 before a bout with the mumps. “Magee in Trim,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 12, 1912: 9.

8 El Paso Herald, June 17, 1907: 2.

9 “Catcher Kling Will Not Play with Champs,” Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois), March 21, 1909: 25

10 “Carlos Smith Leads the Team in Hitting,” The Times (Shreveport, Louisiana), May 9, 1909: 9.

11 “Harmon’s Fine Work Against Sand Crabs,” Shreveport Journal, May 11, 1909: 6.

12 “Harmon’s Fine Work Against Sand Crabs.” 6-7.

13 “Pitcher Harmon Sold to St. Louis Nationals; Joins Team at Once,” Shreveport Journal, June 18, 1909: 1.

14 “Cardinals Secure Two More Pitchers,” Post-Dispatch, June 19, 1909: 6.

15 “Sale of Good Ball Player Deplorable,” Shreveport Journal, June 19, 1909: 10.

16 “Miller Bats in Two Runs and Game is Won,” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, June 25, 1909: 9.

17 “Game Sidelights,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 15, 1909: 8.

18 “Owner Robison is Eager to Perpetuate a Spring and Fall Series,” Post-Dispatch, December 25, 1910: 45.

19 Post-Dispatch, October 15 and 18, 1911.

20 “Only Five Men of Local Teams to Winter Here,” Post-Dispatch, October 18, 1911: 8.

21 “Baseball Gossip,” Ekalaka (Montana) Eagle, August 15, 1913: 3.

22 W. J. O’Connor, “Harmon Might Win More if He Used Fast Instead of Curve Ball,” Post-Dispatch, June 3, 1912: 12.

23 “Nab Bob Harmon as Speeder,” Globe-Democrat, August 18, 1912: 8. Harmon visited traffic court at least three times in a 15-month span. The third time he came before Judge Kimmel he asked for and was granted a change of venue. Post-Dispatch, November 6, 1913: 10.

24 “Cardinal Pitcher Fined as Speeder,” St. Louis Star and Times, August 19, 1912: 1.

25 “Allison Forces Run Over in Tenth and Cardinals Are Victors, 7-6,” Globe-Democrat, October 10, 1912: 7.

26 “Weilman Shuts Out Cardinals,” Globe-Democrat, October 13, 1912: 52.

27 “How Browns-Cardinals Battles Were Decided,” Post-Dispatch, October 17, 1912: 21.

28 “Pitcher Harmon Signs Ten-Week Stage Contract,” Post-Dispatch, December 17, 1912: 19.

29 “Bob Harmon to Wed Soon,” Globe-Democrat, October 8, 1913: 12.

30 “Bob Harmon to Quit Baseball?,” Kansas City Star, November 27, 1913: 8.

31 Cooper, Hickory Bob, 24-25.

32 “Bob Harmon Will Retire from Game,” Shreveport Journal, March 26, 1917: 10.

33 Ed F. Balinger, “Jimmy Archer Signs to Play Baseball in Corsair Uniform,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, March 10, 1918: 18.

34 “Murmurs from Missouri,” Pittsburgh Daily Post, June 29, 1918: 8.

35 “Bob Harmon Severs All Connection with the Game; Given Release,” Shreveport Journal, March 2, 1923: 3.

36 “Hamp Moore Sells Plantation to Bob Harmon for 40 Thousand,” News-Star, October 13, 1922: 1.

37 “Association Harmon Idea,” News-Star, October 29, 1936: 48.

38 “Jes’ Ramblin’,” Morning World, September 22, 1956: 7.

39 “Harmon to Manage Monroe Ball Team,” Town Talk (Alexandria, Louisiana), March 27, 1924: 7.

40 “Optimist Breakfast,” News-Star, February 19, 1952: 3.

41 Paul Martin.

42 “Ouachita Farm Life Satisfies Baseball Star.”

Full Name

Robert Green Harmon

Born

October 15, 1887 at Liberal, MO (USA)

Died

November 27, 1961 at Monroe, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.