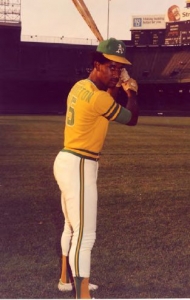

Claudell Washington

“There is virtually nothing he can’t do,” said Willie Stargell.1

“There is virtually nothing he can’t do,” said Willie Stargell.1

“He’s the best player for his age I have ever seen or know,” said Reggie Jackson.2

“He’s going to be one hell of a player,” said Gene Tenace.3

These were sentiments shared by many of the teammates, coaches, and scouts who saw such promise in a young kid from Berkeley, California, named Claudell Washington.

Washington, who would become a two-time All-Star and a World Series champion in 1974, came up quickly through the A’s system and made an immediate impact. Beginning his professional career at the age of 17, he had a rare combination of speed and power.

After being called up by the A’s in July of 1974, Washington did nothing but hit and was instrumental in the team’s winning its third straight world championship. Showing tremendous poise at such a young age, the left-handed Washington hit an impressive .571 in that season’s World Series.

Yet with all the lofty expectations, Washington did not become the superstar many projected he would be. He was often platooned and used as a fourth outfielder, and was criticized at times for his defense. He did have a lengthy 17-year major-league career, however, appearing in 1,912 games and hitting .278/.325/.420, with 164 home runs, 1,884 hits and 824 RBIs.

Washington does have his place in the history books, however. Among other accomplishments, he is one of only 14 players to hit three home runs in a single game for each league at least one time. He also holds the dubious distinction of being the batter struck out the most by Nolan Ryan in the Hall of Famer’s 27-year career (39 K’s in 90 at-bats).

Nicknamed Champ by his father and SuperWash by his teammates, Washington played for seven teams and was traded five times. Between 1974 and 1990, he played for the Oakland A’s, Texas Rangers, Chicago White Sox, New York Mets, Atlanta Braves, California Angels, and the New York Yankees (twice). Although he had some pop, throughout his career he was mostly a line-drive hitter. Despite his home-run total, he never hit more than 17 in a season. Lifetime, he was a .278 hitter who hit over .300 only twice.

What Washington was really blessed with was speed. He stole at least 30 bases four times, including 40 in 1975. (As of 2014 his 312 thefts rank 153rd all-time). He reached the postseason three times, making appearances with the A’s (1974 and 1975) and the Atlanta Braves (1982). He hit .333 in 39 playoff at-bats.

Claudell Washington was born on August 31, 1954, in Los Angeles. He was the oldest of four boys and two girls. His mother, Jenny, was an important figure in his life, as his parents were divorced after 25 years of marriage and he wasn’t close to his father, Claudell Washington Sr. His brother Donald played for three seasons in the Dodgers and A’s organizations.

“I grew up in a good neighborhood,” said Washington, an African-American raised in Berkeley. “Life was pretty easy. There were no gang fights or anything.”4

Washington didn’t play baseball until he was 11, when he began playing in numerous sandlot leagues, as well as Little League, Pony League, and Colt League. “I wasn’t one of those guys who sat around and dreamed about being a professional baseball player,” Washington said. He played baseball during summers “because my friends did it. I wanted to run with them … so I picked up a bat and a ball and did what they did. It was just one of those things where it came natural to me. I had good eye-hand coordination.”5 In 1965 he helped lead his team to victory in the Berkeley Little League championship game, hitting two grand slams, a double, and a triple. He also brought his team to the Little League World Series.

Still, Washington never played on the Berkeley High School team. “I didn’t want to play baseball there because I had preferred basketball and track. I was a high jumper. … In junior high I’d been a pitcher and I started our team’s first five games. Nobody cared whether I hurt my arm or not, so I quit the team. (He was 14 years old at the time.) I didn’t want to go through that in high school.”6

Washington graduated from Berkeley High in 1972, the year he was discovered by a police officer who did some scouting for the A’s.

Washington was recommended to the officer, Jim Guinn, by the Berkeley High athletic department. “I sent him a form, he filled it out and he returned it,” recalled Guinn. “He’s a loner. Someone had to encourage him. I made a call and got him on the Berkeley Connie Mack team. I watched him for a month and worked out with him every day. During that month he batted about .600 and hit seven or eight home runs. If there had been any scouts around I would have signed him right away. But there weren’t. I had no competition for him.”7

Washington remembered it a little differently. “My manager (in the Connie Mack league), Jim McCray, had played minor-league baseball with Jim Guinn. … I think the Orioles, the Mets and the Pirates looked at me, but nothing ever came of it.”8

In either case, Washington had been working as a janitor at a lawn-sprinkler factory when Guinn persuaded the A’s director of minor-league operations John Claiborne, to sign him as a free agent. Washington’s bonus was $3,000. “I put that money in the bank,” he told the New York Times in October of 1974, “I don’t care about home runs. I just want to be a .300 hitter, spend 10 or 15 years in the major leagues and make a lot of money.”9

At his young age, Washington had developed broad, muscular shoulders. He weighed 190 pounds and was 6 feet ball. A Chicago sportswriter said, “Someone should tell him this isn’t football. He can take off those shoulder pads.”10

The A’s assigned Washington to Coos Bay, Oregon, of the Northwest League, where he made $500 a month. There he met his mentor, manager Grover Resinger. “Grover Resinger helped me with my hitting, with my fielding, and with my baserunning. He kept my confidence up. … He taught me how to handle certain pitches. I couldn’t hit the curve or slider, down and in, at first. He also taught me how to run the bases. I used to take wide turns.11

At Coos Bay, Washington hit .279 with 2 home runs and 15 RBIs in 33 games. He had nine stolen bases. Moving up the chain to Class A Burlington (Midwest League), Washington had a breakout year in 1973. He was named to the Midwest League and National Association All-Star Team. In 108 games he led the league in runs scored (92) and total bases (218). He was second in hitting (.322), RBIs (81), and stolen bases (38), and third in hits (144).

In 1974 Washington was promoted to Birmingham of the Double-A Southern League. He hit four home runs in the first three weeks of the season. The Sporting News described two of them as “real tape-measure shots to rival those hit by Walter Dropo in the ’50s and (Reggie) Jackson and (Dave) Duncan in later years.”12

The A’s needed a left-handed designated hitter and called up the 19-year-old Washington on July 1. At the time he was leading the Southern league in batting (.361), runs scored (64), total bases (168), doubles (23), and stolen bases (33).

“When I leave Birmingham,” he told his teammates, “I’m never coming back. My goal was to make it up here by the time I was 21. … Now that I’m here (with the A’s), I want to stay.”13

Washington made his big-league debut against the Baltimore Orioles on July 5, 1974. Pinch-hitting for second baseman Ted Kubiak, he flied out to left. The game that really opened people’s eyes to Washington came three days later. A sellout crowd of 47,582 was on hand at the Oakland Coliseum because Cleveland Indians pitcher Gaylord Perry, who was 15-1, was on the mound attempting to win his AL record-tying 16th consecutive victory. Serving as Oakland’s DH and hitting second in the order, Washington was making his first major-league start. Perry struck him out in his first at-bat, but Washington got his first big-league hit, a triple, in the eighth inning.

Perry and A’s starter Vida Blue were both going the distance in what would become a 10-inning game. With the Indians leading 3-2 in the bottom of the ninth, Gene Tenace drove in the tying run with a sacrifice fly. In the bottom of the 10th Washington drove in pinch-runner John Odom with a single for the winning run. He had played the role of spoiler, and despite striking out 13, Perry was tagged with his second loss of the season.

Impressed, New York Times sportswriter Leonard Koppett wrote, “Gaylord Perry’s winning streak is over, and in the long run the player who ended it may become the better remembered of the two.”14 A’s manager Alvin Dark said of Washington, “He has the kind of future you really get excited about.”15

“He was very impressive even before the winning hit,” said A’s captain Sal Bando, “He was relaxed, waiting on pitches instead of lunging. He has strong wrists and forearms.”16

“That’s when I knew,” said Washington, “that I’d be here for good.”17

Washington told sportswriters he had never even heard of Perry before a televised game in Boston in late June. Asked if he was nervous, Washington replied, “I don’t know anything about him. I wasn’t nervous because I was concentrating too hard.”18

Owner Charles Finley, in what he called a “retroactive pay raise,” gave Washington a $500 bonus for the Perry game and another $2,000 for a 5-for-5 performance in Detroit on August 30.19 For his part, Washington went 3-for-4 in a rematch against Perry in late July.

The team had to make some adjustments for Washington with his arrival, adjustments that Washington acknowledged may have stepped on some toes. “They moved Joe Rudi from left to first to make room for me. He didn’t want to make the transition. I don’t blame him. He was a Gold Glove out there. I understand that.” Speaking about his relationship with A’s superstar Reggie Jackson, Washington said, “Reggie might have acted better. I was stealing his thunder at the time, getting a lot of media attention that used to be his.”20

In 73 games with the A’s Washington batted .285 with six stolen bases in 14 attempts, five triples, and 19 RBI.

Washington always maintained a sense of humor and a “Joe Cool” attitude about his performance. Asked how excited he was playing in the World Series as a 20-year-old rookie, Washington said, “Not very. I get more excited watching pro basketball games on TV.”21

In the 1974 postseason, despite losing Game One, the A’s came back to win the best-of-five ALCS 3-1 over the Orioles. Washington hit .273 (3-for-11) in that series with a pinch-hit double in Game One, a 6-3 loss to the Orioles. The A’s went on to claim their third straight world championship, defeating the Los Angeles Dodgers in five games. Washington appeared in every postseason game, including starts in Games Four and Five of the World Series. He was 4-for-7 (.571) with a .625 on-base percentage.

On Opening Day of 1975 Washington became the youngest player (20 years and 220 days old) to start on Opening Day for the A’s. He played left field and batted eighth. For the season Washington led the team in batting average (.308) and stolen bases (40). He became the regular left fielder and because of his speed and tendency to hit line drives, manager Alvin Dark had him bating third. He played 114 games in left field. He hit his first major-league homer on April 16, off Kansas City Royals right-hander Nelson Briles in Kansas City.

Washington had an outstanding first half of the season (.315, 100 hits, and 32 steals) that he was picked to play in the All-Star Game. Asked if it was his biggest thrill of the year to be named to the AL squad, Claudell quipped, “No, Watching the movie’ Jaws was. … Man, that scared me to death.”22

Washington had a much more serious scare just a few days before the All-Star Game, when he experienced blackouts and dizzy spells. After a series of medical tests, he was cleared to play. In his first of two All-Star appearances, Washington went 1-for-1, with a single and a stolen base.

He finished the season second in steals (40), fifth in batting average (.308), and fourth in hits (182); He hit 10 homers and 7 triples, and drove in 77 runs.

As for the team itself, the A’s were unable to bounce back from the offseason loss of Catfish Hunter, and were swept by the Boston Red Sox in the ALCS.

Before the start of the 1976 season, new A’s manager Chuck Tanner moved Washington from left field to right field, a position he would play most of his career. Washington’s defense was suspect, and he would carry the label as a below-average outfielder. He had, in fact, led the American league in outfield errors in 1976, with 11. Regardless of offensive production, the fourth outfielder/platoon stigma seemed to continue to plague him the rest of his career. Offensively, Washington was still productive. Despite a mediocre .257 batting average, his speed enabled him to steal 37 bases and leg out six triples.

The A’s dynasty began to fall further apart with the advent of free agency. After Hunter became a free agent before the 1975 season, Reggie Jackson signed with the Orioles during the spring of ’76. This was the beginning of the end, as most of the championship team began to become dismantled. During spring training of 1977, Washington himself left the A’s in the first of five career trades. On March 26 he was dealt to the Texas Rangers for second baseman Rodney Scott, left-handed pitcher Jim Umbarger, and cash.

Although he got off to a hot a start with his new club (Washington was hitting .348 in late June), he was unhappy with what he felt was a lack of leadership and teaching of fundamentals. “Nobody was taking charge, not the manager … anybody. … Neither manager Frank Lucchesi nor any of his coaches had bothered to go over such things as cutoff plays.”23

Washington also wasn’t given any explanations regarding his playing time. “After Frank Lucchesi was fired as manager they brought in Billy Hunter. … I was hitting .366, playing every day. The Royals came to town for a doubleheader, with two lefties pitching. I had six hits and seven RBIs. That evening Hunter called me into his office and said Kurt Bevacqua would play against lefties. No explanation. No nothing.”24

“That ticked me off,” said Washington. “From then on I couldn’t deal with it. And the tag followed me my whole career.”*25

Washington played only one full season with Texas, finishing with a .284 batting average, 21 steals, 12 homers 68 RBIs, and 112 strikeouts. On May 16, 1978, the Rangers traded him to the Chicago White Sox with outfielder Rusty Torres for Bobby Bonds for Washington.

It was a troubled season for Washington. He reported to the White Sox 112 hours after the trade. (A traded player generally had 72 hours to join his new team.) Apparently he had been nursing a sore ankle, an injury he claimed he had sustained playing basketball during the offseason.

White Sox owner Bill Veeck was furious at the Rangers for dealing what he referred to as “damaged goods.” The Rangers “told us that he would be ready to play the next day (after the trade). Obviously, that wasn’t the case, ” Veeck complained.26 Veeck went so far as to lobby the league for additional compensation. American League President Lee MacPhail upheld the trade, ruling that “There was no apparent fraud of deceit on the part of the Texas club.”27

In Chicago Washington gained a reputation for lackadaisical play and loafing. “I never had anything against playing for Chicago,” he said. “But I was depressed at being traded twice in a short time, so I didn’t come here with a positive attitude.”28

Washington played in only one game for an entire month after the trade, hitting the disabled list almost right away. He finished his first season with the White Sox playing in 86 games (he played 12 with the Rangers), hitting .264 with 6 home runs, and 31 RBIs. He again played poorly in the outfield, making eight errors.

The next year was no different. Washington made seven errors in right field. South Siders showed their displeasure in many ways. During a game at Comiskey Park, a banner in right field sarcastically read “Washington Slept Here.” There were more serious incidents. “They (the fans) threw M-80s [firecrackers] at me in the outfield,” he said.29

One of the few highlights of Washington’s Chicago career came on July 14, 1979. In a game against the Tigers he launched home runs off pitchers Steve Baker, Milt Wilcox, and Dave Tobik. In the 12-4 White Sox victory, Washington went 3-for-5 with five RBIs and three runs scored

After two trying seasons in Chicago, the Sox traded Washington to the New York Mets on June 7, 1980, for career minor-league pitcher Jesse Anderson. The lowly Mets saw in Washington a much-needed left-handed power bat. His stay in New York was brief, but there was no lack of effort. “He plays hard and he seems to like the atmosphere around here,” said Mets manager Joe Torre. “A guy who isn’t happy wouldn’t play as well as he has for us.” Summarizing Washington’s career, Torre said, “He’s probably a guy who can play regularly but not in our situation where we use four outfielders.”30

Washington had only one hit in his first 17 at-bats with the Mets, but broke out of his slump in a big way two weeks after joining the team. On June 22, in the Mets’ 9-6 win at Dodger Stadium, he had another three-homer performance, hitting them off Dave Goltz (twice) and Charlie Hough. At the time he was one of only three players to hit three home runs in a game in both leagues (Johnny Mize and Babe Ruth were the other two). 11 others have accomplished the feat since for a total of 14.

Washington created a stir when he became a free agent after the 1980 season. Rejecting a contract extension offer from the Mets, he signed a five-year deal with the Atlanta Braves. The $3.5 million contract made Washington one of the highest paid players in baseball. Front-office executives throughout the game were unhappy with owner Ted Turner’s new prize, fearful that the deal would affect the free-agent market, that other players who had generally underperformed might ask for similar money, if not higher.

“People talked about me being an ordinary outfielder because of the numbers in Chicago,” said Washington. “But I hit 10 home runs and drove in 42 runs in 79 games in New York. I was ready and I was swinging the bat good. It was a good investment for Atlanta.”31

In the end, Washington had some of his most productive seasons with the Braves. In 1981, he hit .291 to lead the team and picked up his defense, finishing third in fielding percentage among right fielders (.993). In 1982 Washington had one of his best all-around seasons, proving some of his detractors wrong and showing that he still had athleticism, durability, and talent. Washington played a career-high 150 games, hitting 16 home runs and a career-high 80 RBI. His running game picked up as well; his 33 steals were his most since the 1976 campaign with Oakland.

The 1982 Braves were a talented bunch with Bob Horner, Dale Murphy, and Chris Chambliss. The team won the National League West after a tight race with the Dodgers and Giants. But they lost three straight to St. Louis and were eliminated in the NLCS. Washington was 3-for-9 with a couple of walks in what turned out to be his last postseason games.

In his fourth season with the Braves, Washington hit career-high 17 home runs. He was once again selected as an All-Star. In a 3-1 NL win at Candlestick Park, he was 1-for-2 as a right-field replacement for Darryl Strawberry.

Despite the accomplishments on the field, it was off-the-field issues with substance abuse that put Washington into the headlines. He entered rehab in 1983 for use of cocaine and was arrested in 1985 for possession of marijuana. He was one of the players implicated in the Pittsburgh cocaine trials and was suspended for 60 days by Commissioner Peter Ueberroth. Like other players, however, Washington was able to avoid serving the suspension after donating a percentage of his salary to drug-treatment programs.

Instead of letting Washington leave the Braves as a free agent after the 1985 season, Ted Turner offered him a one-year deal. Washington initially turned down the offer until manager Chuck Tanner offered him a starting spot in right field and a leadoff spot in the order in 1986. “I don’t care about what happened in the past,” said Tanner. “What happened with anybody else doesn’t mean anything to me.”32

Apparently the Yankees agreed. On June 30 they acquired Washington and utility infielder Paul Zuvella in exchange for veteran outfielder Ken Griffey Sr. and utilityman Andre Robertson. Between Atlanta and New York, Washington had rather unremarkable numbers: 94 games played, 11 home runs, 30 RBI, and 10 stolen bases. He re-signed with the Yankees after the season.

Washington’s 2½ years in New York after the trade would have to be considered a success, with 1988 being his last great season. At the age of 33, he was able to stay healthy enough for 126 games, most of which were played in center field. He had an impressive .308/.342/.442 slash line and hit 11 homers, drove in 64 runs, and stole 15 bases. His off-the-field issues seemingly in the rear-view mirror, Washington also had the admiration of his teammates.

“Claudell’s someone who has the respect of everybody. He’s the one who gets us up when we’re down,” said Don Mattingly.33 “He’s done everything we asked,” said manager Lou Piniella. “And he’s been a force as far as chemistry and leadership on this club.”34

The 1988 club managed to stay in the race most of the season, while Washington had some memorable moments. On April 20 in a road game against the Minnesota Twins, Washington hit the 10,000th home run in Yankees history, the most of any franchise. Near the end of the season he hit his only two career walk-off home runs in a span of three days. On September 9, in the second game of a crucial four-game series against the Detroit Tigers, Washington hit a solo shot in the bottom of the ninth off Walt Terrell. Two days later in the series finale, Washington hit a dramatic 18th-inning home run to complete a sweep and move the Yankees into sole possession of second place. His two-run homer off Tigers closer Willie Hernández ended one of the longest games in Yankees history, an 18-inning marathon that last 6 hours and 1 minute.

During the offseason, Washington signed with the California Angels as a free agent. Angels GM Mike Port told the Los Angeles Times why the team made the decision to sign the free agent: “First, Claudell did hit .300 in the American League last year and he played center field in (spacious) Yankee Stadium,”…But we wanted him for his less tangible skills as well.”35

Washington finished just one year of a three-year contract. He was traded a fifth and final time on April 29, 1990, back to the Yankees. The Angels sent Washington and reliever Rich Montelone to New York in exchange for outfielder Luis Polonia. Washington played just 33 games with the Yankees and retired after being released during the offseason.

By 2004, Washington was running a construction company in Oakland and was married to Denise Nolden, president of Contra Costa College in San Pablo, California. He was previously married to Cynthia Anita Callaway. The couple had three children, Camille Snowden, Claudell Washington III, and Crystal, who died in 2007. Except for A’s alumni reunion events, he largely remained out of the spotlight.

Notes

1 Gerry Fraley, “Puzzling Claudell Thinks Positive,” The Sporting News, April 11, 1986.

2 Bruce Markusen, A Baseball Dynasty: Charlie Finley’s Swingin’ A’s (Haworth, New Jersey: St. Johann Press, 2002) .309.

3 Leonard Koppett, “Rookie Who Beat Perry Touted,” New York Times,July 10, 1974.

4 Ron Bergman, “A’s Discover Mr. Kleen in Super Wash,” The Sporting News, August 9, 1975.

5 Steve Kroner, “Second hit was a single highlight for Washington,” San Francisco Chronicle, July 17, 2004.

6 Dave Anderson, “The Kid in Left Field for the A’s,”,Sports of the Times, Hall of Fame file , October 18, 1974..

7 Bergman, “A’s Discover.”.

8 Anderson.

9 Ibid.

10 Bergman, “A’s Discover.”

11 Ibid.

12Wayne Martin, “Claudell Washington Blooming in A’s New Crop at Birmingham,”The Sporting News, June 29, 1974.

13 Ron Bergman, “Hot Swinger Claudell —Another Finley Find,” The Sporting News, September 28, 1974.

14 Koppett.

15 Ibid.

16 Ibid

17 Anderson.

18 “Who’s Gaylord? A ‘s Hero Didn’t Know,” Akron Beacon Journal, July 9, 1974.

19Markusen.

20 Michael Kay, “Claudell takes center stage,” New York Post, July 24, 1987.

21 Unidentified news clipping, November 8, 1974, from Washington’s Hall of Fame player file.

22 Thomas Rogers, article from July 8, 1975 found in Washington’s Hall of Fame file.

23 The Sporting News, June 11, 1977.

24 “Claudell Takes Center Stage: Road Warrior Finally Finds Home in Bronx,” New York Post, July 14, 1987.

25 *Ibid. This may be a Washington quote but facts don’t reflect his comments. Hunter came to the Rangers as manager in late June when Washington was hitting under .320. His quote seems to indicate or suggest having six hits and seven RBIs against the Royals in a doubleheader. Retrosheet does not show a doubleheader being played between Texas and Kansas City. Nor does the record show Bevacqua playing against the Royals for Texas in 1977.)

26 Joe Goddard, “White Sox Are Up In Arms Over Washington’s Ankle,” The Sporting News, June 10, 1978.

27 “A.L. Rejects Chisox Protest,” unattributed July 8, 1978, article in Washington’s Hall of Fame player file.

28 Richard Dozer, “ChisoxClaudell Joins Elite: 3 HR Salvo,”,Chicago Tribune, August 4, 1979.

29Kay.

30 Jack Lang, New York Daily News, August 2, 1980.

31 Larry Whiteside, “He’s Still Bouncing: Angel Claudell Washington Lands on His Feet Again,” Boston Globe, May26, 1989, 71.

32 “Puzzling Claudell Thinks Positive,” unattributed April 11, 1986, article in Washington’s Hall of Fame player file.

33 Kay.

34 Ibid.

35 John Weyler, “A Leading Man: Angels Signed Washington for More Than His Playing Ability,” Los Angeles Times, March 14, 1989.

Full Name

Claudell Washington

Born

August 31, 1954 at Los Angeles, CA (USA)

Died

June 10, 2020 at Orinda, CA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.