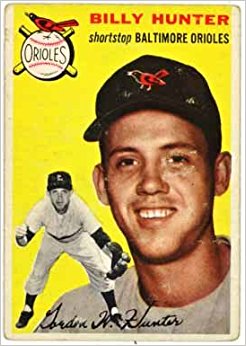

Billy Hunter

Billy Hunter played shortstop with a flashy glove, great team spirit, and a zest for the game. The Brooklyn Dodgers thought he could someday succeed Pee Wee Reese. But as things turned out, they traded Hunter away before he reached the major leagues, and by the time Reese retired, Hunter was playing out the string.

Billy Hunter played shortstop with a flashy glove, great team spirit, and a zest for the game. The Brooklyn Dodgers thought he could someday succeed Pee Wee Reese. But as things turned out, they traded Hunter away before he reached the major leagues, and by the time Reese retired, Hunter was playing out the string.

Gordon William “Billy” Hunter was born on June 4, 1928, in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania. His father grew up with Mike Ryba, who spent lots of time with Dodgers boss Branch Rickey in the Cardinals organization in the 1930s and moved to the Red Sox organization in 1941. Shortly after the 1946 World Series, Ryba contacted Hunter and expressed interest in his shortstop abilities. Hunter had accepted a football/baseball scholarship to attend Penn State, beginning in 1947. However, Penn State did not take any freshmen on its State College campus to leave room for servicemen returning from World War II, so Billy attended Indiana State Teachers College in Indiana, Pennsylvania. He then enrolled at Penn State as a sophomore (1948) for spring football practice and played as a T-formation quarterback. In reality Hunter wanted to play professional baseball. When the Brooklyn Dodgers invited him to Vero Beach, Florida, for 1948 spring training, the 19-year-old met Mike Ryba again (Ryba was then managing the Red Sox’ Scranton club, who were training in Cocoa Beach). Mike had been waiting for Hunter to give him a call and Billy had been waiting for Ryba’s call. Not wanting to wait any longer, Hunter signed a contract with the Dodgers for $2,000. Ryba tried to talk him out of it, saying, “You know what the Dodgers are like? They have 21 farm clubs.” Billy replied, “If I have it, I’ll get there. If I don’t have it, it wouldn’t make any difference whether I was in the Red Sox camp or in the Dodgers camp.”1

Hunter spent five seasons in the minors before reaching the majors in 1953. He played for Three Rivers (in the Canadian-American League) in 1948, for Nashua (New England League) and Newport News (Piedmont League) in 1949, and for Pueblo (Western League) in 1950. In 1951 and 1952 he was with the Fort Worth Cats in the Double-A Texas League before being sold to the St. Louis Browns in October 1952. The ’52 season had been Hunter’s best in the minors, as he sported a .285 batting average with 174 hits in 161 games. He knocked in 75 runs and stole 24 bases. His roommate for his two seasons with Fort Worth was Don Zimmer.

Hunter’s 1952 Texas League MVP season put him at the top of every general manager’s wish list. Browns owner Bill Veeck pried Hunter away from the Dodgers in exchange for $95,000 plus three players, Ray Coleman, Stan Rojek, and Bob Mahoney, making Billy the highest priced rookie in team history. Hunter found out about the trade while reading the New York Daily News in Puerto Rico, where he was playing winter ball. He called his wife, who confirmed it by finding a story in the New York Times. The league minimum salary was $5,000, and Veeck signed Hunter for a salary of $6,000. According to Hunter, “Veeck apologized for only being able to pay me $6,000. ‘Bill, we’re bankrupt,’ he told me, ‘but I’ll take care of you next year.’ Well, you know what happened next year.”2 The Browns moved to Baltimore under new ownership. The shortstop didn’t get the raise.

At the age of 25, Hunter began his major-league career, debuting for the Browns on April 14, 1953, as the team’s Opening Day shortstop. He hit his first home run on September 26, the next to last day of the season, off Connie Johnson of the Chicago White Sox. It was the final home run in St. Louis Browns history. Before the next season the franchise was transferred to Baltimore. In his first season in the majors, Hunter played in all 154 games (152 at shortstop), garnering 124 hits in 567 at bats (.219) for the Browns, who finished in the American League basement with a 54-100 record. Despite his low batting average at the end of the season, Hunter was hitting well enough at All-Star time to make the American League team for the All-Star Game, representing the Browns along with Satchel Paige. He didn’t get to bat in the game, but he pinch ran for Mickey Mantle. “I was in the top 10 in hitting at the end of June,” Hunter later said. “I always joke that I must not have got another hit the rest of the year because I ended up at .219!”3 His career average in 630 major-league games also turned out to be .219.

A solid fielding shortstop, Hunter often played deep in the hole. He told Sports Collectors Digest in April 1997 that “I could come in on ground balls very well and playing deep gave me more range, so I would have a whole lot of assists.”4 This attitude helped him to save Bobo Holloman’s no-hitter on May 6, 1953, with a dazzling defensive gem, a play that Holloman later called the greatest he’d ever seen. The field was wet from an earlier rain, but Hunter snared a line drive up the middle off the bat of Joe Astroth. It should have gone through the middle, as St. Louis’s surface was usually “like concrete,” but the shortstop dove for the ball, caught it, and threw out Astroth from his knees. Hunter later said, “The funny thing about it was that there were only 2,000-some people there to see Holloman’s no-hitter because of the bad weather.”5 The Browns beat the Athletics, 6–0, in the sole no-hitter of the major-league season.

Before the next season the Browns became the Baltimore Orioles. Billy noticed right away a change from the Browns organization, later describing the trip from St. Louis to Baltimore in John Eisenberg’s From 33rd Street to Camden Yards: “When we got to Camden Station, we got into convertibles and made the trip from downtown out to the park. It was unbelievable. There were people everywhere. I was in a car with Vern Stephens and Vinicio Garcia, the three of us in back, up on top, throwing balls or something out to the crowd. People were hanging out of windows. It was a big deal, like we won the war or something. We were thinking, ‘What a huge difference from St. Louis.’”6 The Orioles finished their first season with a 54-100 record, matching the ’53 Browns, but they drew over a million fans to the park, compared with just under 300,000 for the Browns in 1953. Hunter was third on the team in games played (125), second in stolen bases (5), and third in triples (5). He had 100 hits in 411 at bats (.243).

After the 1954 season Hunter was part of the massive 17-player trade between the Orioles and the New York Yankees. The big names were Hunter and pitchers Don Larsen, and Bob Turley, all of whom went to the Yankees. The trade was started on November 17 and completed on December 1. Hunter spent most of 1955 and all of 1956 with the Yankees. After 98 games as the regular shortstop in 1955, he was optioned to Denver in the American Association to make room for Enos Slaughter on New York’s active roster. The Yankees brought him back in 1956, but Hunter played in only 39 games behind Gil McDougald, getting 21 hits in 75 at bats. Hunter’s biggest disappointment in professional baseball was being on the roster for the 1956 World Series and not getting into a game. The Yankees played seven games while Hunter warmed the bench.

In early 1957 Hunter was involved in a 12-player deal between the Yankees and Kansas City Athletics. In an interview many years later he remembered hitting two home runs off Hall of Famer Early Wynn in a game on August 17, 1957, then squeezing in the winning run in the bottom of the ninth. But he managed only a .191 average in 116 games for the Athletics, who finished seventh. After batting a disappointing .155 in 22 games in 1958, Hunter was traded to Cleveland, where he played in 76 games and batted .195. After the season the Indians sent him to San Diego of the Pacific Coast League.

In 1959 Hunter smacked eight home runs, batted .249, and scored 51 runs for the Padres, in what proved to be the end of his playing career. After the season his contract was sold to Toronto in the International League. In a 1992 interview he recalled thinking, “At age 31, if I can’t get back to the big leagues after the season I just had, then I might as well retire.”7 He had told Toronto owner Jack Kent Cooke that the only way he would play again in the minors would be as a player/manager. Cooke had hired Mel McGaha the day before as manager, so Hunter retired. Hoot Evers was the acting general manager for Cleveland and offered Hunter a part-time job scouting players in the International League. The pay was $3,000 plus expenses. The next year, Evers offered him the same opportunity. In the meantime Lee MacPhail of the Orioles offered him a full-time scouting position, which Hunter accepted.

In 1962 Hunter managed the Orioles rookie team in Bluefield, West Virginia, with the understanding that if a coaching opportunity on the Orioles opened up, he would be considered for it. Hunter piloted Bluefield to consecutive Appalachian League pennants. Speaking in 1992, the skipper was extremely proud of the fact that he had managed shortstop Mark Belanger in Bluefield and later Belanger’s two sons, Rich and Rob, at Towson State University.

In 1964 Hunter’s former Yankee teammate Hank Bauer was named manager of the Orioles, and he hired Hunter as the third-base coach and base-running instructor. In 1968, when Bauer was fired, the Orioles hired Earl Weaver to manage. Hunter was clearly disappointed, but Weaver rallied in support of Hunter, telling the press, “I really think I need him.”8 Hunter stayed on for nine years under Weaver. In the not uncommon event of Weaver being ejected from an Orioles game, it was often Hunter who took over the reins for the duration. In fact, Hunter managed the Orioles in the fourth game of the 1969 World Series (a 2-1 loss to Tom Seaver and the Mets), when Weaver became the first manager in 34 years to be ejected from a World Series game.

In 1974 Hunter displayed a new gimmick. When an Oriole hit a home run, Billy would unbutton his shirt and display his T-shirt to the crowd. There was only one word on the shirt: ZAP. The New York Daily News called the gimmick “bush.”9 In May 1975, the coach was struck by a line drive off the bat of future Hall of Famer Rod Carew, fracturing Hunter’s left arm. It didn’t deter his enthusiasm. Hunter was a loud coach, often described as feisty. In 1975 Jim Martz, a columnist for the Miami Herald, called Hunter “a throwback to the days when baseball was peppered with hoot ‘n holler guys.” Martz quoted Hunter as saying, “I just wouldn’t know how to act if somebody on the center-field wall couldn’t hear me.”10

During his 13½ years as the Orioles’ third-base coach, Baltimore enjoyed unprecedented success. The Orioles won two World Series titles (1966 and 1970), four American League pennants, and five AL East titles. Frank Robinson, noted as the “judge” in the Orioles’ Kangaroo Court, credited Hunter with starting the Court “as a way to loosen the club up and point out some mistakes at the same time. Laugh and get a point across in a light atmosphere.”11

Hunter was named the Texas Rangers’ manager on June 28, 1977, the fourth Texas manager of the season, accepting a three-year, $250,000 contract. (The Rangers had fired Frank Luchessi and replaced him with Eddie Stanky, who quit after two games claiming homesickness. Connie Ryan managed eight games before Hunter accepted the job.) Bill, as he now became known, guided the Rangers to a second-place finish with a 60-33 record, and the rookie skipper received considerable mention in the Manager of the Year balloting, won by his former boss, Earl Weaver. At the end of the 1977 season, Hunter told reporters that “our crying need is a big RBI man. And we could use a starting pitcher. I’m satisfied with our defense and our bullpen, but we need a man who can drive in 90 to 100 runs.”12

Texas first baseman Mike Hargrove described playing under Hunter: “He came in here and showed a perfect blend of knowing how to handle people, plus knowing the game. If you took a jar, put Billy Martin and Frank Lucchesi in that jar, shook it up, then emptied it, out would come Billy Hunter. He combines the best qualities of both our previous managers.”13

The successful skipper was offered either a three-year or five-year contract in the middle of the 1978 season, but he wanted a one-year contract instead. Hunter had become disenchanted with long-term contracts and didn’t see how to motivate players with long contracts. In addition, his wife had no desire to live in Texas. The latter sentiment had a lot to do with his decision to turn down the offers. In a strange turn of events, Hunter was fired on the second-to-last day of the 1978 season, despite a record of 86-75, which had the Rangers in second place. Shocked by his dismissal, Hunter vowed that he would never manage or coach in the majors again. He called the president at Towson State University, outside Baltimore, and became the head baseball coach, leaving the major leagues for a salary of $5,000. The Rangers installed Pat Corrales at the helm.

In 1979, Hunter’s first season at Towson State, he guided the Tigers to an 18-10 record. In 1981 he commented that the biggest difference between college and professional ballplayers lay in the fundamentals. “That was the biggest adjustment I had to make,” he said. “The players in college aren’t as well versed in the fundamentals. I found I was taking a lot for granted. You have to do a lot more teaching.”14 One of the best things he liked about coaching at Towson was that the field was only three miles from his house.

One of Hunter’s assistant coaches was Ron Hansen, who left in the middle of the 1980 season to join the Milwaukee Brewers’ coaching staff. One of his players at Towson, left-handed pitcher Chris Nabholz, became only the second player in the school’s history to make it to the major leagues. (The first was Al Rubeling.) Drafted in the second round of the 1988 draft by Montreal, Nabholz pitched in the majors for six years, compiling a 37-35 record with a 3.94 earned-run average.

In 1984, Hunter was named the athletic director at Towson, an NCAA Division I program. He served in the dual role of baseball coach and athletic director for three years before turning the program over to his longtime assistant Mike Gottlieb. Hunter’s baseball coaching record at the collegiate level ended at 144-166-3.

Towson enjoyed unprecedented athletic success during Hunter’s 11 years as the director of athletics. The Tigers men’s basketball team made back-to-back appearances in the NCAA Tournament in 1990 and 1991 and the men’s lacrosse team played for the national championship in 1991. The Towson baseball team went to the NCAA Tournament in 1988 and 1991, and the gymnastics team was a nationally-ranked program and finished ninth in the nation in 1991.

Hunter married his wife, Beverly, in 1949. They had two sons (Gregory, born in 1953, and Kevin, born in 1961) and four grandchildren. The Hunters settled in the Baltimore area when Hunter was the Orioles shortstop in 1954. As of 2010, they had lived in the same home in Lutherville since 1955. Hunter retired as Towson’s athletic director in 1995. In 1996, he was inducted into the Baltimore Orioles Hall of Fame. In 1997 he was inducted into the Towson University Athletic Hall of Fame.

Sources

Hunter, Billy. Two interviews for the SABR Oral History Project were provided by Eileen Canepari of the SABR office. I accessed the February 17, 1992, interview conducted by Paul Brown and the April 28, 2003, interview conducted by John Grega.

Various articles, Towson University media guides and 1978 Texas Rangers media guide provided by Dan O’Connell, associate director of athletic media relations, Towson University. Received December 2008. Mr. O’Connell’s assistance is greatly appreciated.

Various undated articles and newspaper clippings in Gordon W. Hunter’s file at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Research Center, the National Baseball Hall of Fame & Museum, Cooperstown, New York, received December 2008. Special thanks to Gabriel Schechter for his assistance.

Notes

1 Billy Hunter, interview from the SABR Oral History Project dated April 28, 2003, conducted by John Grega.

2 St. Louis Browns Fan Club Spring Newsletter 2006 clipping in Hunter’s Baseball Hall of Fame file.

3 Ronnie Joyner, “Billy Hunter”, undated drawing in Hunter’s Baseball Hall of Fame file.

4 Sports Collectors Digest, April 18, 1997.

5 Billy Hunter, interview from the SABR Oral History Project dated April 28, 2003

6 Billy Hunter, interview from the SABR Oral History Project dated February 17, 1992, conducted by Paul Brown.

7 Hunter, interview, 1992.

8 The Sporting News, July 27, 1968.

9 New York Daily News, June 15, 1974.

10 The Miami Herald, March 8, 1975.

11 Hunter, interview, 1992

12 Unknown source clipping in Hunter’s Baseball Hall of Fame file, dated October 15, 1977.

13 The Sporting News, August 27, 1977.

14 Hunter, interview, 2003.

Full Name

Gordon William Hunter

Born

June 4, 1928 at Punxsutawney, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.