Carroll Hardy

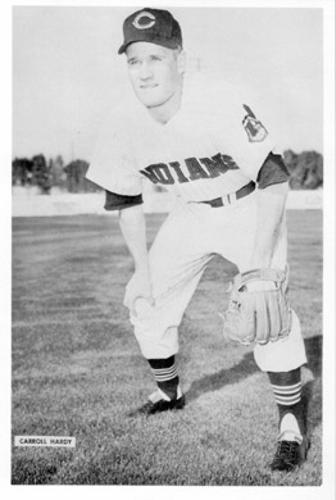

Outfielder Carroll Hardy played for four major-league baseball teams between 1958 and 1967. Over time he has come to be known largely for one at-bat, in which he hit the ball back to the pitcher in the first inning of a late September game of almost no consequence in the standings, but most of his professional career was in NFL football.

Outfielder Carroll Hardy played for four major-league baseball teams between 1958 and 1967. Over time he has come to be known largely for one at-bat, in which he hit the ball back to the pitcher in the first inning of a late September game of almost no consequence in the standings, but most of his professional career was in NFL football.

“His long career in professional sports, as a player and executive,” wrote Jerry Crowe in the Los Angeles Times, “had a sort of Forrest Gump quality to it.”1 His career connected with Y. A. Tittle, Joe Perry, Hugh McIlhenny, and John Elway of football, and Ted Williams, Roger Maris, and Carl Yastrzemski of baseball.

Hardy lettered in three sports at the University of Colorado — baseball, football, and track. He was All-Conference in both baseball and football, and initially chose football over baseball and was a bowl MVP in his only season with the San Francisco 49ers. After service time in the Army, he was ready to re-enter professional sports but this time chose baseball over football. And yet, after his days playing baseball were down, it was back to football, where he worked 23 years for the Denver Broncos, ending his career as director of pro personnel.

Carroll William Hardy was born in Sturgis, South Dakota, on May 18, 1933. Sturgis was a small city of around 2,000 inhabitants at the time, and became famous for its annual motorcycle rally. The first rally occurred in 1938, with nine participants. The 2015 rally drew 700,000 people to a city that still has fewer than 7,000 inhabitants.

Walter Hardy was a rancher and Hazel Hardy a housewife. Walter also opened a filling station and garage in Sturgis. They had three children — Dale, eight years older than Carroll, and Janice, seven years younger. Brother Dale was “an outstanding athlete and an inspiration to Carroll” who went on to receive advanced schooling through the Navy program at the University of Colorado at Boulder. He became a coach and athletic director at Spearfish College, now Black Hills State University.2

Except for his sophomore year in high school, which he spent in Yuma, Arizona, when the family moved there for a year due to his mother’s health, Carroll attended the Sturgis public schools, graduating from Sturgis High. The high school did not have a baseball team, but he played American Legion ball for three years during high school. He played basketball in Yuma as a starting guard. In the summer of 1951, back from the year in Yuma, he was selected to play in a national high school All-America football tournament in Memphis. The past winter, he’d led the basketball team to the 1951 Class-A state championship.

Carroll had been given a tryout with the St. Louis Cardinals the summer before going to college but declined to sign a contract, “deciding that a college education was more important.”3 He attended the University of Colorado at Boulder, a decision he made in part because Dale had attended the university.

An extraordinary all-around athlete earning 12 letters in three sports in four years, Hardy enjoyed an outstanding career at Colorado. He was a broad jumper on the track team, competing only during the indoor season to avoid a conflict with baseball. His .392 average and 12 triples were career marks at the university and attracted attention from baseball scouts.

But Hardy gained his greatest fame on the football field. His first play in college resulted in a touchdown over Colorado A&M (now Colorado State University) on September 22.4 Newspaper accounts of the day commented on the freshman halfback’s quickness on the field, as he averaged 7.9 yards per carry.5 It was written that he “runs as if he were on springs.”6 As a kick returner in 1952, he was second in the NCAA, averaging 32.2 yards per return. Stanley Woodward named him second-team All-American in his 1954 season preview. Hardy averaged almost a first down per play, carrying the ball 70 times for 642 yards. In his college finale, on November 20 against Kansas State (a 38-10 Colorado win), he averaged more than 20 yards per run (238 yards in 10 carries). For the season, he scored nine touchdowns and kicked 14 PATs, his 68 points ranking eighth in the nation in a low-scoring era; his 41.6-yard punting average ranked him fifth nationally. He was All-Big 7 and third-team All-America according to the Newspaper Enterprise Association, and on January 9, 1955, he was named MVP of the Hula Bowl as the College All-Stars beat the Hawaii All-Stars (which included a number of pros.)7 To cap off his senior year, he met his future wife, Janice Mitchell, a freshman and beauty queen who had dated his roommate.

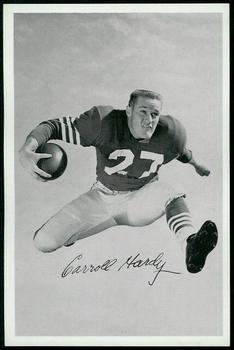

Hardy was drafted by the San Francisco 49ers, selected in the third round of the draft. At the same time it was noted that one or more major-league baseball teams had been bidding for his services.8

In June, it was reported that he had signed to play baseball with the Cleveland Indians.9 In a questionnaire he returned to SABR, Hardy credited his signing to farm director Laddie Placek and GM Hank Greenberg.10 Both teams — the 49ers and the Indians — agreed he could try to play both sports.11 In signing with the Indians, he had passed on the opportunity to receive a signing bonus so that he could play more regularly; under the bonus rules of the day, he would have had to be on the Indians’ roster, and likely sitting on the bench, rather than get the development time in the minors.12

Cleveland assigned him to play in the Eastern League (Class A) for the Reading Indians. He appeared in 53 games, batting .265 with five home runs. It was a solid enough start for someone in his first season of professional baseball. Near the end of August, before Reading’s season was over, he joined the 49ers.

Hardy’s year with the 49ers showed considerable promise. He played in the team’s first two games, missed the third and fourth, appeared in the remaining eight. He saw little action in his first three games, seeing the ball just five times for 11 yards. In his fourth game, a 38-21 win over Detroit, he ran the ball once for two yards and caught his first NFL pass, a 78-yard touchdown (the Niners’ longest play of the year) from Y. A. Tittle. He followed up with a remarkable stretch over the next three games: four catches for 51 yards and a score in a 27-14 loss in Los Angeles; a catch for a 64-yard gain in a 7-0 loss in Washington; and his best day as a pro, four catches for 122 yards and two touchdowns (33 and 58 yards) in a 27-21 loss in Green Bay. Then it all dried up. In the 49ers last three games, two of them losses, he carried the ball nine times for 24 yards and caught two passes for 23 yards. Hardy’s season added up to 15 carries for 37 yards and 12 passes caught for 338 yards (28.17 yards per catch) and four touchdowns. His four touchdowns were second only to Billy Wilson’s seven on the team. He was back in the Hula Bowl again, this time playing for the Hawaii All-Stars, and reeling off a 97-yard run on a pass from Tittle.

Hardy’s year with the 49ers showed considerable promise. He played in the team’s first two games, missed the third and fourth, appeared in the remaining eight. He saw little action in his first three games, seeing the ball just five times for 11 yards. In his fourth game, a 38-21 win over Detroit, he ran the ball once for two yards and caught his first NFL pass, a 78-yard touchdown (the Niners’ longest play of the year) from Y. A. Tittle. He followed up with a remarkable stretch over the next three games: four catches for 51 yards and a score in a 27-14 loss in Los Angeles; a catch for a 64-yard gain in a 7-0 loss in Washington; and his best day as a pro, four catches for 122 yards and two touchdowns (33 and 58 yards) in a 27-21 loss in Green Bay. Then it all dried up. In the 49ers last three games, two of them losses, he carried the ball nine times for 24 yards and caught two passes for 23 yards. Hardy’s season added up to 15 carries for 37 yards and 12 passes caught for 338 yards (28.17 yards per catch) and four touchdowns. His four touchdowns were second only to Billy Wilson’s seven on the team. He was back in the Hula Bowl again, this time playing for the Hawaii All-Stars, and reeling off a 97-yard run on a pass from Tittle.

By February 1956, the Plain Dealer reported that Hardy thought he had enough of a chance to make the Indians that he was considering giving up football.13 He was assigned to Triple A, to the Indianapolis Indians. Playing football had been tough, and that may well have been a factor in his decision-making. “Football is fun,” he told sportswriter Harry Jones. “Pretty rough, though.” Jones then explained that Hardy had had his front teeth knocked out in a game against the Baltimore Colts, suffered torn rib cartilage in an exhibition game against the Cleveland Browns, and was knocked unconscious not once, but twice, by the Chicago Bears.14 For his part, Hardy said, “I like pro football, but if I do as well in baseball this year as I hope to, I’ll give up football. It’s not for financial reason either. I suppose I could make as much money playing eight years of pro football, but you never know when you’ll get hurt and have your career finished. Anyhow, I think I can do better in baseball.”15

Indians manager Al Lopez said, “It’s only a question of time…If he doesn’t make it, nobody will. I’ve never seen a guy with more natural ability.”16 Hank Greenberg reportedly gave him an ultimatum around the end of March — baseball or football.17

The United States Army made the decision for him. He was instructed to report for duty on May 21. Before his draft board gave him the word, he had hit for a .365 average in 21 games for Triple-A Indianapolis. He was assigned to Fort Bliss in Texas (and played football there in the autumn), but the Cleveland Indians spoke up and he stopped.18 It was only years later that an MRI revealed “layers of scar tissue from injuries suffered during his military service” — injuries he played through.19

Carroll and Janice were married in August 1956. They had three children — Jay, Jill, and Lisa.

During a furlough from the Army, Carroll stopped in Tucson and worked out a bit with the Indians in February 1957. He was discharged in February 1958 and joined the Indians for spring training. While characterizing Hardy as “of virtually unlimited potential,” Gordon Cobbledick of the Plain Dealer said he was “nervous and tense with anxiety to make good at once” and “hasn’t been notably impressive this spring.”20 Cobbledick noted that Rocky Colavito was looking far worse.

Debuting on April 15, Hardy walked in his first plate appearance. He pinch-ran and scored a run in his second game, and then walked again in his third. It wasn’t until his fifth game that he finally got an at-bat. He was 0-for-3 but collected his first RBI on a sacrifice fly. On May 9, in his seventh game, he got his first base hit — a double.

A two-run single beat the White Sox, 4-2, on May 11. Hardy’s first home run came in the first game of the May 18 doubleheader. It was the bottom of the 11th inning and he was asked to pinch-hit for Roger Maris. Billy Pierce of the White Sox had just taken over in relief, with one out and two Indians on base. Hardy homered right down the left-field line to win the game, 7-4.21

Then he didn’t play again until June 27. On May 20, he was hospitalized with acute appendicitis. He’d been hitting .265, but saw his average drop to .204 by June 12 and “at his own request” asked to be optioned to the Pacific Coast League’s San Diego Padres.22 In July, he gave notice that it would be baseball rather than football. He didn’t do a whole lot better for San Diego, though, hitting .235 in 57 games. He knew he hadn’t produced, but he also knew he had to play more to be able to develop. He asked to be sent to Denver in 1959, if he weren’t with Cleveland, so at least he’d be closer to home.23

Hardy was due to be called up to Cleveland once the PCL season was done, but Janice had just given birth to Jay, and he requested instead to stay at home for a month, and then go play winter ball. He played in Venezuela for the Gavilanes de Maracaibo.

He made the Indians again in 1959 and was batting 1.000 after his first game, a 2-for-2 day, but it was all downhill from there — quite a long way downhill. He was down to .105 by May 23. He bumped it up to .125, but when he slipped under .100 there was little more the Indians could hope for. After appearing in 23 games, many as a pinch-hitter and a few as a pinch-runner, Hardy was batting .094 with no runs batted in. On June 29, the team optioned him to Seattle and acquired veteran Elmer Valo from Seattle. There he hit .254 in 66 games.

Perhaps he was simply trying too hard. At the end of March, he had told Jim Piersall, “I wish I was flaky like you, so I could relax. I’m so damn tense I don’t know what I’m doing out there half the time.”24 A few years later, he told Houston Post writer Clark Nealon, “I know my problem is to find a way to relax at the plate, but it’s been hard to do when you feel like you’re trying for a regular job every time you go up there. And when you’re in there only against left-handers. It always seemed I was on the bench a week, then when I started there was Whitey Ford or somebody like that on the mound. I’d be better off as a hitter I guess if I had a devil-may-care attitude up at the plate, but I’m not made that way.”25 He added, “In football, you could really rip somebody and the tension was relieved. Baseball has much more pressure on the individual than football.”26

In September he came back to Cleveland and appeared in seven games; his year-end major-league average was .208.

He spent the offseason in Boulder, selling investments for a Boulder brokerage, but also working out at the university, taking batting practice, while (this was quite innovative at the time) studying film of himself that GM Frank Lane had paid to have made.27

Hardy batted and threw right-handed and was said to look “more like a football player than a baseball player, the most solid sort of 195-pound 6-footer.”28

Manager Joe Gordon had both Hardy and Piersall competing for an outfield position in 1960. Piersall won out. After 29 games, Hardy was batting .111 with one RBI, mostly having played in pinch roles. On June 13, he was included in a trade to the Boston Red Sox, going with catcher Russ Nixon for Ted Bowsfield and Marty Keough. Nixon was the key to the deal for Boston. Of Hardy, Red Sox manager Mike Higgins said, “I saw Hardy in Spring [sic] training at Scottsdale a year ago and he looked great. But apparently he never realized his potential while with Cleveland. Maybe can come up to that with us.”29 After seeing Hardy for a couple of months, albeit in limited action, Higgins praised his speed and his arm: “He’s a third-base coach’s dream. Never any worry about sending him in to score. He can just about outrun that ball. In addition, he has the best arm in the outfield.”30

Hardy had a chance to play with the Red Sox. He got into 73 games, with 145 at-bats, and hit .234 with 15 RBIs. He started 15 games in left field, 11 in center, and 10 in right, and appeared in 23 other games as a later-inning outfield replacement. Not swinging the bat gave him a game-winning RBI on September 3, as he drew a bases-loaded walk in the bottom of the seventh to give Boston a 5-4 win. On September 10, two singles and a two-run homer helped the Sox win, 7-4, and earning Hardy a few more headlines.

Hardy’s most remembered at-bat came on September 20 in Baltimore. The Red Sox were in seventh place, 23 ½ games out of first place. In the top of the first inning, the Red Sox had a runner on first base and nobody out. Hal Brown was pitching, and Ted Williams was at the plate. Williams fouled a ball hard off his right ankle and, in the words of trainer Jack Fadden, “his foot was swollen as big as a baseball.”31 In too much pain to continue, he had to leave the game. Carroll Hardy took his place in the batter’s box — thereby becoming the first (and only) person to ever pinch-hit for Ted Williams. On the first pitch, he tried to lay down a bunt but popped it up to Brown, who threw to first base to double Willie Tasby off the bag.

After Williams homered in the bottom of the eighth on September 28, in his last at-bat in the major leagues, he ran out to his position in left field in the top of the ninth, only to be beckoned back in by the manager so that the fans at Fenway could give him one final ovation. Running out to take his place in left was Carroll Hardy.

Given his combined .221 batting average for 1960, some of Hardy’s friends urged him to get back in to football, perhaps to play for the Boston Patriots.32 For whatever reason, Hardy received one vote in Rookie of the Year voting.

In 1961, Hardy played in 85 games for the Red Sox and had his best season. He played all three outfield positions (center field more than the others) in 85 games, accumulated 312 plate appearances, and had career bests in batting (.263), on-base percentage (.330), and RBIs (36). He helped win some games (his 12th inning hit won the second game of the July 16 doubleheader against the White Sox) and had some big games (a second-inning grand slam against Los Angeles put the Red Sox ahead to stay in the August 25 game), but for the most part it was a consistent season from beginning to end.

On May 31, 1961, Hardy pinch-hit for Ted Williams’ replacement in left field, rookie Carl Yastrzemski. It was at Fenway Park. The Yankees were winning, 7-4, and Hardy stepped in for Yaz to lead off the bottom of the eighth. He bunted for a single, and three batters later came around to score. No one knew that Yaz would become a Hall of Famer, but looking back we see that Hardy pinch-hit for Roger Maris, for Ted Williams, and for Carl Yastrzemski.

He started 1962 with a bang, 2-for-3 in his first game and a single, a double, and a 12th-inning game-winning grand slam in the second game which accounted for all the runs in the 4-0 game against the Indians, a complete-game win for Bill Monbouquette. Higgins had dubbed him the team’s starting right fielder: “He earned the job, and it’s his. I doubt anybody can run him out of there.”33 Hardy hadn’t been trying to swing for the fences, he explained after the game: “All I wanted to do was to hit a sacrifice fly.”34

After running down a hard-hit ball and making a spectacular catch on June 6, Hardy himself noted how baseball — more than football — put the spotlight on the individual player. “A player is on a spot every time a ball is hit to him, and every time he goes up to the plate. He’s out there on his own with everybody in the park getting a good look at him. It’s a little different in football, especially for the guys in the line. Only the coaches have an idea what’s going on there, and they want to see the movies. But football sure gives you a lot of action.”35

He won a couple more games with his bat in early June, but as the season wore on, his average declined from one month to the next. He played in 115 games, 30 more than any other year, and he had 112 more plate appearances, but he only matched his 36 RBIs of the year before and his batting average dropped from .263 to .215. That was not good enough to keep him as a regular in the outfield, as the eight-place 1962 Red Sox looked ahead to the season to come.

On December 13, the Red Sox made their fourth trade in a 12-month period with the Houston Colt .45s, a straight player swap of Hardy for the more veteran utility outfielder, Dick Williams. No one could have guessed it the time, but in 1967, Williams was the manager of the Red Sox and won the American League pennant. As a manager, particularly for his leadership of the Oakland A’s, Williams became a Hall of Famer.

Hardy didn’t play much at all for Houston, only 15 games in 1963, the final one coming on May 8. On April 14, he drove in the tying run and scored the winning run in a 5-4 win over Sandy Koufax and the Dodgers. But he drove in just two other runs, and was batting .227. When it was time to cut rosters, he was optioned to Oklahoma City on 24-hour recall. He saw no further action with Houston in 1963, but had a very good season at Triple A, batting .316 in 123 games with 16 homers and 61 RBIs for the Oklahoma City 89ers.

In 1964, it worked the other way around — he started with the 89ers and had an exceptional half-season with them, batting .321 in 79 games, with 14 homers and 58 RBIs. On July 8, he was called up to Houston, trading places with Rusty Staub. He stuck with the Colts the rest of the season, but it was a discouraging experience. He appeared in 46 games, but only hit for a .185 average with 12 RBIs. Two of those RBIs came on a tie-breaking two-run homer in the first game of the August 2 doubleheader against the New York Mets. Houston finished in ninth place, albeit 13 games ahead of the Mets.

In April 1965, Hardy was traded to the Minnesota Twins for minor-leaguer Joseph Christian. He spent all of 1965 and 1966 with the Twins’ Triple-A team, the Pacific Coast League Denver Bears. This gave him the opportunity to play in his adopted hometown. He hit an even .300 in 124 games in ’65, with 63 RBIs, but dropped off in ’66 (.259 in 114 games with 36 RBIs.)

In 1967, he played most of the year for Denver once more, batting .298 in 80 games with 26 RBIs — and he played in his last major-league games, 11 games in September, nine of them in pinch roles and two in late-inning defense. He was 3-for-8 in his limited time at the plate. He homered once and drove in two. His last appearance was on September 27, but he was in the on-deck circle ready to bat in the top of the ninth inning on October 1, the day the Twins lost to the Red Sox at Fenway Park and lost the American League pennant to the Impossible Dream Red Sox. Had Rich Rollins not popped up to Rico Petrocelli for the final out, Hardy would have come to bat.

In 1968, Hardy was one of two managers, with James Merrick, for the short-season Single-A Northern League team in St. Cloud, Minnesota. The Rox led the league with a 43-27 mark.

One wonders, of course, how he would have fared had he chosen football instead. In his major-league career, over parts of eight seasons, he had 1,259 plate appearances and hit for a .225 average with 17 homers and 113 RBIs.

After baseball, as it happened, Hardy’s post-playing career was mostly in football. In early 1969, he was named assistant ticket manager for the NFL’s Denver Broncos. By 1970, he was the director of scouting for the Broncos.

As Director of Player Personnel he worked for the Broncos for 20 years, with one Super Bowl appearance in 1977 (Super Bowl XII). In 1981, he was named assistant general manager. He helped assemble the Broncos teams that reached the Super Bowl in 1987 and 1988.

In 1979, Hardy was inducted into the Colorado Sports Hall of Fame. In 2002, he was inducted into the University of Colorado Athletic Hall of Fame.

In May 1986, he returned to Fenway Park and played in the Equitable Old-Timers Game, playing for the Red Sox alumni team against a team of all-stars. He came within inches of hitting a grand slam, but had to settle for a two-run single off the wall; the alumni team lost, 5-4.

In 1987, Hardy resigned from his position with the Broncos, retiring to a cabin in Steamboat Springs, Colorado. He took a position scouting football for the Kansas City Chiefs and worked at that for two years before deciding he preferred spending more time in Steamboat Springs and less time traveling.

One memento of note is a photograph given him by Broncos quarterback John Elway, inscribed, “Thanks for all the mental support.”36

Naturally, Hardy’s career attracted attention when two-sport star Bo Jackson successfully played both professional baseball and professional football in the late 1980s and into the 1990s, until a hip injury put an end to his football career. Jackson played in both baseball’s 1989 All-Star Game and football’s 1990 Pro Bowl.

For 11 years he worked as a lift host on the mountain for the Steamboat Ski Corp., interacting with guests at the gondola as well as skiing, snowmobiling, and hunting. With their children all living in Denver, Jan and Carroll moved back to the front range of the Rocky Mountains and lived in Longmont, Colorado. He enjoyed playing golf several times a week and getting together with some senior football and baseball buddies, talking sports past and present.

Jan Hardy wrote in 2017, “It has been an exciting and fulfilling life we’ve been fortunate to experience. He still receives requests for autographs nearly every week. Life has slowed down but by no means have our adventures stopped. Our two daughters have 30-plus years with United as flight attendants, which afforded us with the opportunity to do a lot of traveling. Our son who has recently retired from the Army as a major was our personal guide throughout Europe where he spent 13 years in Germany. He has returned to Denver working as a physicians attendant/golfing partner for Carroll.” 37

Looking back on his baseball career at one point, Hardy told Jim Burris of the Denver Post, “I’d like to have people remember me for hitting 400 home runs and a lifetime batting average of .305, but I didn’t do that. But it’s not bad being remembered as the only man to ever pinch-hit for Ted Williams.”38

He died at the age of 87 on August 9, 2020, from complications due to dementia in Highlands Ranch, Colorado.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Jan Finkel and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also consulted Hardy’s player file and player questionnaire from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, the Encyclopedia of Minor League Baseball, Retrosheet.org, Baseball-Reference.com, Rod Nelson of SABR’s Scouts Committee, the SABR Minor Leagues Database (online at Baseball-Reference.com), ESPN College Football Encyclopedia, Stanley Woodward’s Football 1954, College Football at Sports-Reference.com, Pro-Football-Reference.com, and the South Dakota Sports Hall of Fame website (www.sdshof.com/inductees/carroll-hardy).

Notes

1 Jerry Crowe, “Meet the Only Man to Pinch-Hit for Ted Williams,” latimes.com, August 31, 2009, at latimes.com/sports/la-sp-crowe-next31-2009aug31,0,7998800.column

2 Information about the Hardy family comes from Carroll and Jan Hardy, in a letter written to the author by Jan Hardy on May 18, 2017.

3 Jan Hardy letter.

4 Associated Press, “Colorado Rallies to Top A&M, 28-13,” Charleston (South Carolina) News and Courier, September 23, 1951: 20.

5 Floyd Olds,” Hardy No. 1,” Omaha World-Herald, April 26, 1952: 9.

6 Margery Miller, “Carroll Hardy’s Run to Fame,” Christian Science Monitor, December 2, 1954: 27.

7 Associated Press, “Hardy Voted Top Player,” Omaha World-Herald, January 10, 1955: 9.

8 Lewis F. Atchison, “Win, Lose or Draw,” Evening Star (Washington DC), January 28, 1955 45.

9 Associated Press, “Hardy Signs with Tribe,” Aberdeen (South Dakota) Daily News, June 13, 1955: 8.

10 Questionnaire submitted to SABR on February 12, 2004.

11 Associated Press, “Hardy To Play in Two Sports,” Columbus Dispatch, June 13, 1955: 13.

12 “The 22 year old turned down a bonus contract in order to play regularly.” — Associated Press, “Hardy, Colorado Start, Signs with Indians,” Chicago Tribune, June 14, 1955: B1.

13 James E. Doyle, “The Sport Trail,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 28, 1956; 29.

14 Harry Jones, “Tribe Rookie is ‘Hardy’ Individual,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, March 18, 1956: 48.

15 Ibid. It was later said that he would have made about $5,000 more playing for the 49ers in 1958 than for Cleveland. See Associated Press, “Ex-Buff Athlete May Forfeit $5,000 to Stay in Baseball,” Omaha World-Herald, April 2, 1958: 28.

16 Ibid.

17 Wire services, San Diego Union, March 30, 1956: 21.

18 Wilbur Adams, “Between the Sport Lines,” Sacramento Bee, January 1, 1957: 19. Adams mistakenly placed him at Fort Hood.

19 Valerie Singleton, untitled article, Daily Times-Call (Longmont, Colorado), March 25, 2007: 25.

20 Gordon Cobbledick, “Plain Dealing,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, April 11, 1958: 35.

21 Umpire Ed Hurley’s call was a controversial one. See “Homer ‘Fouls Up’ Sox,” Chicago Tribune, May 19,1958: C1,

22 “Indians Option Hardy, Call Up Two Players,” Milwaukee Journal Sentinel, July 14, 1958: 23.

23 Jack Murphy, “Lane Rekindles Metkovich Row; Hardy Wants More Daily Action,” San Diego Union, March 11, 1959: 26.

24 Milton Gross, “Piersall Aids Mentally Ill — And Others,” Boston Globe, March 31, 1959: 25. Further on the subject of Hardy and the benefits of relaxation, see “Ed Rumill, “He Doesn’t Care,” Christian Science Monitor, May 16, 1960: 14.

25 Clark Nealon, “Hardy Looks Forward to Chance, Hoping Frustrating Years Are Past,” Houston Post, March 1, 1963.

26 Ibid.

27 “No Loafing for Hardy; He Wants Indian Job,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, February 1, 1960: 25.

28 Arthur Daley, “Tastes of Glory,” New York Times, March 13, 1962: S2,

29 Roger Birtwell, “Mike Picked Nixon,” Boston Globe, June 14, 1960: 33.

30 Bob Gates, “Carroll Turned Back on Grid Stardom,” Christian Science Monitor, August 30, 1960: 11.

31 Larry Clafin, “Ted Flies Home; May Be Through,” Boston American, September 21, 1960: 39.

32 “Hardy Urged To Join Patriots,” Boston American, September 26, 1960: 36. The newspaper said it was likely Hardy would do so.

33 Ed Rumill, “Harry ‘Arrives’ At Fenway,” Christian Science Monitor, April 12, 1962: 10.

34 Hy Hurwitz, “Benchrider Hardy Blooms As Socker in Hub’s Garden,” The Sporting News, May 2, 1962: 33.

35 Harold Kaese, “Hardy Makes Like Piersall,” Boston Globe, June 7, 1962: 44.

36 Valerie Singleton.

37 Jan Hardy letter.

38 Jim Burris, “Carroll Hardy is the Only Player Ever to Pinch-Hit for Ted Williams. But That’s Not His Only Claim to Fame,” Denver Post, May 31, 1993.

Full Name

Carroll William Hardy

Born

May 18, 1933 at Sturgis, SD (USA)

Died

August 9, 2020 at Highlands Ranch, CO (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.