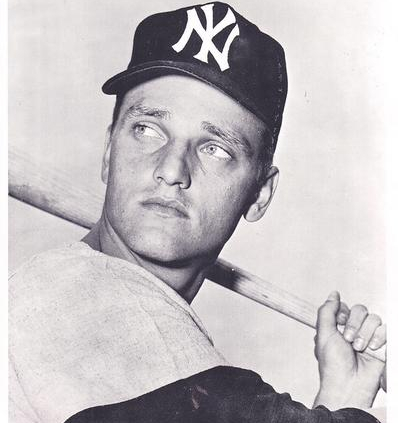

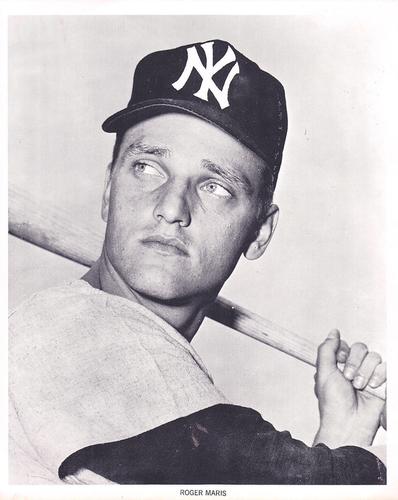

Roger Maris

With one extraordinary season Roger Maris secured his place in baseball history. And yet his establishment of the major league home run record in 1961 proved to be more of a personal curse than a professional triumph. It also overshadowed, indeed overwhelmed, the totality of a career characterized at least as much by his consistent and important contributions to a string of League and World Championship teams–in both leagues throughout the 1960s–as by any single slugging accomplishment.

With one extraordinary season Roger Maris secured his place in baseball history. And yet his establishment of the major league home run record in 1961 proved to be more of a personal curse than a professional triumph. It also overshadowed, indeed overwhelmed, the totality of a career characterized at least as much by his consistent and important contributions to a string of League and World Championship teams–in both leagues throughout the 1960s–as by any single slugging accomplishment.

The future home run king was born Roger Eugene Maras on September 10, 1934, in Hibbing, Minnesota. His parents, Rudolph and Corrine Maras (née Perkovich), were of Croatian heritage; they were also born in Minnesota. The family moved to North Dakota when young Roger was five, and he graduated from Bishop Shanley High School in Fargo. There he was an athletic legend, once returning four kick-offs for touchdowns in a single game, a feat that remains a national record. Indeed, Maris’s football exploits earned him a scholarship to the University of Oklahoma, but quickly realizing that college life was not for him, he turned his full attention to baseball, where he would make an indelible mark.

An American Legion star whose strong all-around play attracted the attention of many scouts, Maris began his professional career in the Cleveland Indians organization, being first assigned to their Fargo-Morehead club in the Northern League in 1953. Achieving much early success, he moved up the ladder the next year to the Keokuk (Iowa) Kernels, where he quickly demonstrated his all-around talent, tying an Three-I League single season record for put-outs by an outfielder in 1954, while hitting .303. Keokuk was also the place where Maris, who in his early years viewed himself as a contact hitter, discovered his power. His manager, Jo-Jo White, taught him to pull the ball, thus unleashing what would prove to be a history-making force.

His family legally changed their Croatian name to Maris in 1955. The 20-year-old minor leaguer was pleased with the change. He was tired of opposing fans making unflattering rhymes of his name with “ass.”

After hitting just nine homers in his first minor-league season, Maris crushed 69 from 1954 through 1956. His power helped lead the Indianapolis Indians to the 1956 Junior World Series title. In the aftermath of that triumph, expecting to be called up to the parent club the following spring, on October 13, 1956, Maris married his high school sweetheart, Pat Carvell. Together they ultimately would have six children, four boys and two girls, making a family that would serve as an unshakeable foundation for Maris during even the most tumultuous days of his subsequent career. But with those times still ahead, Maris immediately signaled his arrival on the major league scene. After going 3-for-5 in his debut, his next game featured an 11th-inning grand slam that iced a five-run victory. Overall in 1957, he appeared in 116 games, with 14 home runs and 51 RBIs. Though he hit just .235, he drew 60 walks.

Traded in June of 1958 by the Indians to the Kansas City Athletics, a healthy Maris played in 150 total games, stroking 28 home runs and knocking in 80 runs for the two also-rans. His performance the following year earned him a spot in his first All-Star game, and despite missing a number of games in the second half of the 1959 season due to the removal of his appendix, he established himself as a rising star in the world of major league baseball. The Yankees had been watching his development with great interest, and any doubts about Maris’ status as an emerging star were swept aside when they traded for him on December 11, 1959. Determined to get back on top after two years without a World Series crown, the Yankees reached down to what many saw as their unofficial minor league outpost, and acquired Maris in a multi-player trade with the Kansas City Athletics. In addition to Maris the Yankees obtained Kent Hadley and Joe DeMaestri, giving up veterans Marv Throneberry, Norm Siebern, Hank Bauer, and Don Larsen in the deal. To all experienced baseball observers it was clear that that the smooth swinging, left-handed hitting Maris was the centerpiece of the trade.

Slotted to replace Bauer in right field, the twenty-five-year-old Maris was expected to team with Yankee legend Mickey Mantle to anchor a lineup that was determined to return the Bronx Bombers to their accustomed spot atop the baseball world. Initially it appeared a dream match as Maris got off to a quick start, hitting two home runs in his first game in pinstripes. By early August he already had over thirty home runs and over ninety runs batted in as the Yankees, overcoming a slow start, reasserted their dominance of the American League, ultimately winning the pennant by eight games over a surprising Oriole squad. Unfortunately, in a harbinger of future difficulties, Maris suffered a number of late season injuries which limited his playing time down the stretch. However, despite the difficulties causes by his injuries, the left-handed slugger still finished with thirty-nine homers, only one back of league leader and teammate Mickey Mantle, and Maris led the league with an impressive 112 RBI, a performance that earned him the American League Most Valuable Player Award. His regular season effort not only warranted selection to his second All-Star game, but also earned him his only Gold Glove Award, evidence of yet another way he contributed to the Yankees’ turnaround. In the World Series, Maris played a comparatively minor role in the inconsistent Yankee attack. He hit .267 with two home runs as the Yankees, despite outscoring the Pirates 55-24, including 16-3, 10-0, and 12-0 routs, suffered a devastating loss on the historic ninth inning, seventh game walk off shot by light-hitting Pirates second baseman, Bill Mazeroski.

The 1961 season represented a new beginning for the Yankees and baseball. While Major League Baseball, seeking to take advantage of the sport’s continuing popularity as well as the nation’s changing demographics launched new franchises in Los Angeles and Washington (while the former Senators moved to Minneapolis-St. Paul), the Yankees made a change in leadership. Still reeling from the loss to the Pirates, a defeat that coupled with the third place finish in 1959 and the seventh game loss to the Braves in 1957, made the once-dynastic franchise appear mortal, the team fired long-time skipper Casey Stengel. They replaced him with former Yankee catcher Ralph Houk. The change did not pay immediate dividends as the Yankees played only little better than .500 ball through the first two months of the season. However, by early summer they began to get on track and pulling away from the rest of the American League made the pennant race itself little more than an afterthought. Instead, it soon became apparent that the 1961 season was going to be remembered for an unprecedented explosion of hitting power with New York at the center of the fireworks. Ironically, given the way things turned out, Maris was slow to join the power parade, not hitting his first home run until the Yankees’ eleventh game of the season, a game in which Mantle hit both his sixth and seventh. In fact, it was Mantle’s hot start that led to early media talk about an assault on Babe Ruth’s single season record. However, by the end of May, Maris had broken out of his early season slump and with nine home runs over the last two weeks of the month, had brought his total to twelve, only two behind his switch-hitting teammate. Building upon this strong effort, Maris soon surged into the lead. From May 17 when he stroked his fourth through June 22nd, Maris hit twenty-four home runs in thirty-eight games. It was a streak which at the time had only been approached by Babe Ruth’s twenty-four in forty-one in 1927. Meanwhile, for the full month of June, Maris hit fifteen round trippers, and the Yankees, behind Whitey Ford’s record setting 8-0 month and the slugging exploits of M & M boys (as the press had begun to call them), had moved into the thick of the American League race.

As the home runs kept coming, the media coverage began to take on a distinctive cast, and Maris suffered for it. Not only was the most revered record in baseball being put in jeopardy, but it was being done so by an outsider, the new kid from Midwest who not only sought to unseat the iconic Ruth, but was also challenging the reigning king, fan and press favorite, Mickey Mantle. This two pronged-“assault” was not something that Maris could ever win, and while he and Mantle got along fine–they even lived together during the season–the media did everything they could to turn the chase into a rivalry that it was not. In fact, for all the media’s efforts to make it more, on the field Maris and Mantle were teammates who shared a mutual respect for each others’ talents and were simply trying to do their best to propel the team towards another World Series. But that reality was relegated to a back seat as headlines and tabloids increasingly followed the two sluggers’ every move as they continued their march toward the magic sixty with the lead being passed back and forth through July and into September. Four- and five-game droughts without a home run would be followed by a new outpouring of power and as September 1 brought the start of a critical three-game series with the Tigers who were only one and a half games back, Maris had fifty-one while Mantle stood at forty-eight. Knowing what they had to do, the Yankees swept the series with Maris and Mantle both hitting a pair of home runs. The weekend set marked the beginning of a thirteen-game winning streak that settled the matter of the American League crown, and with that business taken care of, the baseball world focused on the continuing pursuit of the Babe.

The media scrutiny that Maris and Mantle had endured previously reached unprecedented heights in September. For Maris in particular, it became almost unbearable. While Mantle had been cordially, if not happily, dealing with the New York press ever since he became the heir to Joe DiMaggio, the plain-spoken, small-town Maris was nowhere near as comfortable in the spotlight. Consequently, the attention and the endless and often redundant questions from the growing number of reporters who were covering the record chase was burdensome, if not downright overwhelming, and with the rules that had once made the locker room an athlete’s sanctuary now forgotten, Maris and his every move were tracked in media that went beyond the sports pages. Mobbed on road trips, hounded in the streets, Maris could not even attend Catholic mass in peace. It was not a life he wanted or accepted–he wanted to be a ballplayer, not a celebrity–and as the pennant and home run races moved toward their climax, he became increasingly short-tempered and distraught, often hiding in the training room to avoid the prying reporters with what he saw as their repetitious and often inane questions. Amidst the tension Maris‘s hair felt out in clumps, and he had trouble sleeping.

As if the pressure itself were not enough, an additional obstacle surfaced when questions arose as to whether it would be a new standard if the record breaking home run was hit in any of the additional games added to the schedule due to expansion. When Commissioner Ford Frick, a former ghost writer and friend of Ruth’s, declared that any new record must be achieved within the old 154-game schedule, it added another level of debate amid questions about his impartiality and objectivity, as well as pressure on the M & M boys. None of this made the challenge any easier, and when injuries landed Mantle in the hospital in late September, ending his run at the record, the burden, the pressure, and the spotlight all shifted directly and exclusively to Roger Maris.

Maris continued on, hitting his fifty-sixth on September 9, but the fifty-seventh did not come until a week later. Number fifty-eight came the next day in game number 152. The Yankees then traveled to Baltimore, Babe Ruth’s hometown. Maris struggled early before hitting number fifty-nine off Milt Pappas in the third inning of game number 154. Three subsequent at-bats yielded only one very long foul ball and a long drive to right center field that was hauled down by Earl Robinson in front of the fence, and so while Maris had become only the second player in major league history to hit fifty-nine home runs, he would not be breaking the record according to Commissioner Frick’s dictates. However, the 1961 season did include 162 games, and Maris took advantage of the full schedule. Back at Yankee Stadium, the left-handed slugger hit his sixtieth off Baltimore right-hander Jack Fisher on September 26. Finally, on October 1 the chase ended. Before a crowd of only 23,154 fans seeking to witness history, Roger Maris hit his sixty-first home run–more than any major leaguer had ever hit in a single season–off Red Sox right hander Tracy Stallard in the bottom of the fourth inning. It was the only run in the 1-0 triumph. The long grueling journey was over. It was not of course the end for Maris or the Yankees as the World Series awaited. It was to be a short series, for while an exhausted Maris hit only .105, the rest of the Yankee juggernaut that had set a major league record with 240 home runs picked up the slack and easily dispatched the Cincinnati Reds in five games.

The off-season was, in some ways no less a blur than the season itself had been, but this time, finally, Maris was being feted for his accomplishments. A second Most Valuable Player Award as well as the Hickok Belt given to the outstanding professional athlete of the year were among the highlights of the busy winter banquet circuit.

While 1962 couldn’t have been expected to match the historic 1961 effort, Maris nevertheless had a strong year and was again a critical cog in another Yankee World Series championship effort. After the unprecedented hoopla of 1961, Maris happily slipped back in the shadow of teammate Mickey Mantle who won his third and final MVP Award. Hitting .256, Maris drove in 100 runs—his third straight season hitting the century mark in that category—while hitting thirty-three home runs. Appearing in 157 games, Maris was a consistent presence in a season in which, Mantle, for all his heroics, missed almost forty games with injuries. While Maris may have slipped at the plate, his all-around skills continued to be critical to the efforts of the aging ballclub. Although he only hit .174 against the Giants in the World Series, he still led the team in runs batted in with five. Too, a single play in the seventh game of the Fall Classic reminded fans across the nation that there was more to Roger Maris than home runs, when, in the ninth inning of game seven Maris arguably saved the championship for the Bombers. With two out and Matty Alou on first, Willie Mays hit a shot into the right field corner. Excited Giant fans were certain that the speedy Alou, running on the two-out hit, would score the tying run, but Maris cut the ball off on its way to the fence, whirled, and threw a bullet to cut-off man Bobby Richardson, and Alou was held at third. When the next hitter, Willie McCovey, hit an almost inhumanly hard line drive right at second baseman Richardson, the Yankees had their twentieth World Series victory in the past forty years.

Plagued by injuries, Maris appeared in only ninety games in 1963, although he still managed to stroke twenty-three home runs while hitting .269. The Yankees, meanwhile, easily won their fourth straight American League flag, but the Bronx Bombers’ bats were silenced in the World Series, as the Dodgers, led by Sandy Koufax, allowed only four runs in sweeping the defending world champs, with Maris, who was only able to play in two games, being held hitless by the Dodger staff. In 1964, Maris bounced back, playing in 141 games while hitting .281 with twenty-six home runs. Although the Yankees struggled initially under the leadership of new manager and long-time field leader Yogi Berra, they hung on to take the junior circuit crown by a single game over the While Sox. However, in the World Series against a young Cardinal team led by the fierce right-hander Bob Gibson, the aging Yankees came up short, losing in seven games in what would be their last post-season appearance for over a decade. Maris for his part struggled, hitting only .200 against the Redbirds.

The following season, 1965, saw the Yankees landing in sixth place–their worst finish since 1925. Maris, dogged by a misdiagnosed broken hand, played only forty-six games, the fewest in his career. Although Mantle and catcher Elston Howard also missed large chunks of the season due to injuries, Maris’ failure to play at a time when the Yankees clearly needed him only added to the distrust between Maris and the press. The ill will that had made parts of 1961 so difficult resurfaced, and Maris’ inability to be Babe Ruth, not to mention Mickey Mantle, or even to perform like the Roger Maris of old, when the team needed someone to carry the burden, left the press and many fans disappointed and angry. The 1966 campaign was little better as injuries again limited Maris to less than 120 games, and his thirteen homers, forty-three RBI, and .233 batting average were only a shadow of the MVP years. While the aging Bombers were falling apart all at once, much of the blame seemed to fall on the former home run champ. For those who had refused to appreciate Maris in the early 1960s, his injury plagued performance in the middle part of the decade, coming when the Yankees as a team were faltering, only seemed to confirm their views. For a man who had never placed any individual accomplishment above winning, it was a difficult time. Indeed, tired of battling injuries, of trying to play, even when hurt, but never seeming to be appreciated for the effort regardless, Maris gave much thought to retirement. However, before that decision could be made, the struggling Yankees traded Maris to the St. Louis Cardinals for third baseman Charley Smith.

St. Louis and the Cardinals proved to be an ideal place for Maris to revive and ultimately finish his career. The gateway to the West was a very different baseball town than New York. The historical crown jewel of the National League, the owner of more World Series banners than all but the Yankees, the Cardinals were a team with a storied past that included the development of the modern farm system under GM Branch Rickey, and personalities like Dizzy Dean and the Gas House Gang. Cardinal fans were known throughout baseball as supportive and knowledgeable. Returning to his Midwestern roots, Maris’s quiet, but important contributions were recognized and valued by fans and media alike. Maris was seen as a veteran who could fill one of the few gaps on a talented squad many of whose members had played important roles in the team’s 1964 World Series victory over the Yankees. Specifically, the acquisition of Maris allowed the Cardinals to move right fielder Mike Shannon to third base, with the ultimate impact being an improved offense. On an all-star laden team led by future Hall of Famers Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, and Orlando Cepeda, free agent revolution catalyst Curt Flood, and future announcer Tim McCarver, and managed by Cardinal legend Red Schoendienst, Maris readily settled into more of a supporting role, happy to do his job away from the glare of the spotlight that he had never sought nor wanted in New York. In a time before interleague play and around the clock media coverage, his new teammates knew little of him beyond what they had read in the papers, but Maris’ team-first approach was evident, and he was well received by his new teammates. The change of scenery clearly lifted Maris’ spirits, and with a new uniform offering the opportunity for a fresh start, Maris even began to again respond to interview requests from the local media. Greeted with a long and welcome ovation when his name was announced on Opening Day, Maris responded with a two-for-five performance that helped Bob Gibson best the Giants and set the tone for a season marked by consistent contributions to what would prove to be a winning effort. The only real addition to a lineup that had finished sixth the previous season, Maris hit .261 in 125 games, knocking in fifty-five runs while offering his usual combination of consistent and savvy play in the field and on the base paths. It was a triumphant comeback, and while no one would deny that Bob Gibson’s pitching exploits were more than enough to warrant the series MVP award, Maris capped the year with the best World Series of his career, driving in seven runs and hitting .385 in a performance that was critically important to the Redbirds winning their second championship in four years.

The 1968 season proved to be Maris’ swan song. Again dogged by injures, a situation that undoubtedly hastened his decision to retire, he was limited to 100 games. Nevertheless, he gamely contributed to yet another championship effort as the Cardinals defended their National League crown, topping the Giants by nine games. In a scene markedly different from his final days in New York, the Cardinals celebrated his retirement with a ceremony before the home finale against the Astros. Unhappily, Maris’ career ended on a disappointing note as the Detroit Tigers, led by left-hander Mickey Lolich, thwarted the Cardinals’ effort to repeat as World Champions. For Maris, who hit .158 against the Tigers, the Series marked the end of a career that had included seven World Series appearances in twelve major league seasons. He had been a key figure on seven pennant winners and three world championship teams, a record unmatched by any other player in the 1960s.

In the aftermath of the 1968 Series, Cardinals owner Gussie Busch set Maris up with a beer distributorship in Gainesville, Florida. The Maris Distributing Company, operated by Roger and his brother, Rudy, served as a distributor for Anheuser-Busch beer in central Florida. Travelling around the state on business, Maris seemed content to leave baseball behind. While he appeared at the Cardinals spring training camp in the early 1970s, the ill feeling that accompanied his parting from the Yankees remained. However, in 1973, a change in the ownership of the Yankees opened the door for a reconciliation between Maris and the team with which he would forever be associated. The new Yankees owner, George Steinbrenner, was a man intent on both restoring the team to its past glory while also connecting his Yankees with their championship heritage. Having moved the headquarters of his company, American Shipbuilding, from Cleveland to Tampa in 1976, he made a concerted effort to reestablish relations with the former Yankee great. A spring 1977 exhibition game provided the venue for a meeting, and while Maris turned down Steinbrenner’s request to come back for the 1977 Old-Timers Game, in April of 1978, with no advance fanfare, he flew up to New York to join Mantle in raising the 1977 American League pennant. A crowd of over 44,000 surprised fans reacted with admiration and appreciation as Maris came onto the field, heavier than in his playing days, but still sporting his trademark crew cut. With chants of “Roger, Roger,” ringing in his ears, it was clear that at least some of the ghosts of 1961 had been buried.

The ensuing years saw Maris enjoying some of his old baseball friends. He appeared at a number of Yankee and Cardinal events, and he began to make regular appearances at spring training. By 1983, with his business booming and able to send a sales force around the state of Florida, a relaxed Roger Maris was able to stay at home overseeing his established enterprise while enjoying golf, friends, and family. Unhappily, around Thanksgiving he began to suffer from headaches, and they continued into early 1984. Initially, he paid them little heed. However, when he experienced some intermittent difficulty breathing at the same time that he developed a growing number of lumps in various places on his body, he sought medical attention. That visit to the doctor and the attendant tests revealed that Maris had lymphoma, cancer of the lymph glands. However, the original diagnosis offered hope for a full recovery and, immediately beginning chemotherapy, Maris was optimistic about his prospects. Further raising his spirits was the announcement by the Yankees that the 1984 Old Timers Game would feature the retirement of his number nine and the addition of a plaque in his honor that would take its place alongside those of other Yankee greats in Monument Park in Yankee Stadium. Appearing at the fabled stadium dressed in a full Yankee uniform as a plaque declaring him “A great player and author of one of the most remarkable chapters in the history of major league baseball” was unveiled, Maris fought back tears as he thanked the many friends and former teammates who had come for the ceremony as well as the new generation of fans who gave him a rousing reception.

As the summer progressed, Maris’s continued treatment seemed to be working, and the cancer appeared to have gone into remission. Maris made what proved to be a final trip to Yankee Stadium in April 1985 when he received the team’s Lou Gehrig Pride of the Yankees Award at a dinner the night before the season opener. The next day, teamed once again with Mantle, who had become a frequent phone caller, regularly checking up on the health of his old teammate, Maris participated in special opening day activities. It had been twenty-five years since Maris had first donned the pinstripes and the standing ovation he received upon being introduced made clear that after all that had transpired Maris had earned a special place in Yankee lore. Unhappily, shortly after returning to Gainesville, Maris’s health began to further deteriorate. A return trip to New York to see a cancer specialist at Mt. Sinai Hospital yielded no relief, and by the end of the summer he had gotten much weaker, stopped going to his office, and was even limiting phone calls. In November Maris was referred to a doctor in Tennessee where he received some experimental treatment, but he continued to fade. A trip to the Anderson Hospital and Tumor Institute in Houston represented the last attempt to combat the disease, but it was to no avail. On Saturday, December 14, 1985, fifty-one year old Roger Maris died. The funeral in Fargo and the memorial service in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York served as impromptu Yankee reunions and the outpouring of emotion and the presence of the elite of the baseball establishment indicated clearly that his accomplishments throughout his career were his true Yankee legacy.

Maris was introduced to a whole new generation of baseball fans in the summer of 1998 as Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa launched their assault on his record. Reflective of how different the public reaction was to the assault on Maris’s record was the fact that there were sold-out crowds at every turn as Sosa and McGwire pursued the record that Maris had in fact held longer then Ruth. It was far cry from the sparse crowd that was in attendance when Maris connected off Tracy Stallard in the 1961 regular season finale. Too, the warm reception given the chase by the Maris family served as a reminder of the quiet way that Maris had gone about his business. He was not seeking to topple the iconic Ruth or the current toast of the town Mantle. Rather, when he was traded from the lowly Athletics to the dynastic Yankees, he saw a chance to contribute to a team that regularly challenged for the championship. The Maris family’s response was a far cry from the response of the baseball establishment and especially the media to Maris’s pursuit of the Babe’s achievements. And yet it reflected their understanding and recognition of its importance to the game, especially in the aftermath of the 1994 strike. It also demonstrated their deep respect for the game that had, for all that he had endured, afforded Roger Maris so many opportunities. Their genuine embrace of McGwire and Sosa represented a marked contrast with the way Maris had been savaged over the years even long after the controversy about the legitimacy of Maris’s record had died, and did much to foster a renewed appreciation of all that Maris accomplished and experienced. The look back in 1998 did much to open people’s eyes to what Maris had gone through in that historic 1961 season. And of course the subsequent reports and revelations of alleged steroid use by some of the pursuers of baseball’s home run records only enlarged and reaffirmed the magnitude of Maris’s accomplishment.

In the end, Roger Maris was a ballplayer caught in the crossfire of a cultural shift. The response to his pursuit of Ruth’s record represented a generational divide as much as the increased emergence of athletes as celebrities did. It was not something with which Maris was comfortable. He was not someone who sought the spotlight, and when it shone in his direction, it left him uncomfortable. Rather, like most athletes in his time, but fewer today, he believed he owed the fans, the owners, and his team his best efforts on the field and that it was on those performances and what they contributed to the team’s effort to win that he would be judged. Anyone who doubted that had only to remember that in the midst of the home run race he had surprised his teammates, not to mention the opponents, with a squeeze bunt to win a game in the midst of a hotly contested pennant race; had only to remember that he was also a man who, drawing upon the full range of his athletic talent, bulldozed an opposing catcher, knocking the ball away, and allowing the Yankees to win another game on the way to the 1961 pennant. A fine fielder with a strong arm, a smart and savvy base runner known for his ability to break up double plays and take the extra base, home runs had never been the only weapon in his arsenal.

In looking at the totality of Roger Maris’ career, there is something very right about the fact that his sixty-first home run not only set the record, but in the 1-0 season finale, represented the winning run, for beyond the records, beyond the individual accomplishments, beyond the controversy about the Hall of Fame, about drug-enhanced modern sluggers, about his relations with the press, Roger Maris was all about winning. It didn’t matter if it was in the American League or the National League, he played to win–and did–and teammates ranging from Mickey Mantle to Bob Gibson, from Whitey Ford to Orlando Cepeda, knew it, respected it, and appreciated it. Roger Maris may have been a reluctant hero, but he was a proven winner. Even in the media saturated world of modern professional sports there is no higher accolade.

Sources

Allen, Maury. Roger Maris. New York: Donald I. Fine, Inc., 1986.

Clavin, Tom and Danny Perry, Roger Maris. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010.

Feldmann, Doug. El Birdos. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2007.

Katz, Jeff. The Kansas City A’s & the Wrong Half of the Yankees. Hingham, MA: Maple Street Press, 2007.

Kubek, Tony and Terry Pluto. Sixty-One. New York: Macmillan Publishing Company, 1987.

McNeil, William F. The Single Season Home Run Kings (2nd Edition). Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2007.

Rosenfeld, Harvey. Still a Legend: The Story of Roger Maris. Lincoln, NE: An Authors Guild Backinprint.com. edition, originally published in 2002.

Smith, Ron. 61*. St. Louis: Sporting News, 2001.

Travers, Steven. A Tale of Three Cities. Washington, DC: Potomac Books, Inc., 2009.

Full Name

Roger Eugene Maris

Born

September 10, 1934 at Hibbing, MN (USA)

Died

December 14, 1985 at Houston, TX (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.