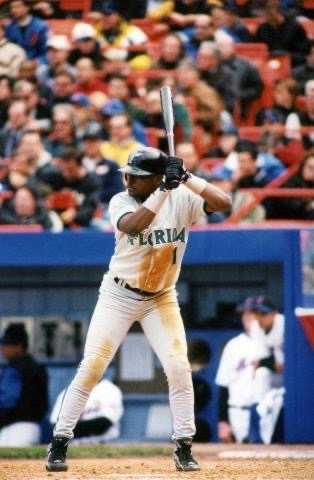

Luis Castillo

The 2017 All-Star Game was played in Miami, so it was natural for major media outlets to give some attention to the franchise hosting it. As one example, less than two weeks before the big event, Fox Sports reposted a FanSided article on the top five candidates among former Marlins to have their uniform numbers retired. On that short list was Luis Castillo.1

The 2017 All-Star Game was played in Miami, so it was natural for major media outlets to give some attention to the franchise hosting it. As one example, less than two weeks before the big event, Fox Sports reposted a FanSided article on the top five candidates among former Marlins to have their uniform numbers retired. On that short list was Luis Castillo.1

Luis Antonio Castillo Donato was born on September 12, 1975, in San Pedro de Macorís, Dominican Republic. His parents, Antonio and Faustina, raised Luis, his two brothers, and three sisters under incredibly humble conditions. Luis and his brothers were crammed into a small bedroom in a cement-block house. The family lived in the city’s core, and its main baseball stadium happened to be just down the street. Luis’s father first worked in a sugar mill but after losing that job resorted to selling fruit from the back of a pickup truck.2

Luis was 6 years old when he began playing baseball, but because he lived in a poorer area, some of his early experience was unusual. “Every boy in San Pedro de Macorís plays baseball in the front of his house with bottlecaps,” reported Luis’s brother Julio César, and they’d be struck with sticks instead of an actual bat.3 As Luis and his friends grew older and took the game more seriously they had to be increasingly creative when it came to equipment. Instead of anything close to a conventional glove, Luis first used part of a plastic milk carton in the field. He would cut off some of it but keep the part with the handle and use it more like a scoop than a mitt.4

Luis didn’t acquire an actual baseball glove, a used one, until he was around 12 years old. Instead of a real baseball, sometimes they made their own from rolled-up socks. When he was old enough to try out for organized teams he obtained a pair of spiked shoes, size 10½, but his feet were more than two sizes smaller so he stuffed the shoes with paper. He used a small workman’s glove as a batting glove. He was able to improve it, he recalled, because he’d go “to the summer league games in the Dominican, and watch every game.”5 He’d also watch players afterward to see if they threw anything away. When one discarded a batting glove that surely was too large for Luis, he peeled off the Franklin logo and fastened it to his workman’s glove. During winter league seasons he had opportunities to watch his favorite player, Alfredo Griffin, but reportedly didn’t actually dream of becoming a major leaguer himself until about a year before he signed his first pro contract.6

Castillo’s makeshift equipment has been credited with helping him build strength, speed, and skill. From swinging his first bat, an iron rod, he developed his wrists, and whenever he was able to use a real glove, it was so much easier to snag a drive than with a milk carton. Thus, when he was 11 he earned an opportunity to travel with a San Pedro team for a regional tournament in Puerto Rico. He could afford to go only because his mother awoke before dawn and made lunches that he took by bicycle six miles away, to sell to workers in the city’s duty-free business park, where his sisters worked in grim sweatshops. Perhaps the most incredible aspect of Luis’s youthful saga is that his bike had only one pedal and no brakes. All of the effort and struggle paid off: Luis’s team won the tournament and he was the leading hitter. He was also grateful to his parents for guiding all six of their children away from lives plagued by crime and drugs. Baseball served as a good distraction. “I was being raised in a dangerous environment. I liked being in the streets and if I didn’t respect my mom, I wouldn’t be what I am,” he said after his first season as a National League All-Star. “Thank God I listened to my mom and dad.”7

For Luis’s 14th birthday his mother gave him his first brand-new glove, a Juan Samuel model. Samuel was born in the same city and had been a major-league All-Star twice by then. “It was real expensive,” Luis said. “I don’t come from a family that has a lot of money, so my mom bought that for me and it was hard for me because I think that’s money she can use to buy food for my family to eat.”8

Nelson Rodríguez, founder of the youth league in which Luis honed his skills, would have considered Faustina naïve if she thought at the time that her son could play in the major leagues in the States. “No one imagined this, not even him,” said Rodríguez, who coached Samuel and several other future major leaguers. “He was skinny and small … very quiet. But with a great desire to get better.”9

“I played baseball because I liked it,” Castillo confirmed. “I didn’t know I was going to be a professional player and be in the big leagues. I would play in the streets and people would be like, ‘Hey, you’re good.’ I didn’t know.”10

According to the 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, Luis graduated from the Colegio San Benito Abad high school in 1991,11 though Kevin Baxter of the Miami Herald said that Castillo dropped out. Regardless, Luis’s sister Maribel, a year old than him, told Baxter that schooling didn’t seem the path to her brother’s goals. “He was serious, but he was also restless,” she recalled. “He never wanted to go to school … because he wanted to play.” Fortunately, a man named Virgilio Reyna decided to recommend Castillo to major-league scouts.12

According to the back of Castillo’s 1995 Kane County Cougars baseball card, the scout who signed Castillo on August 19, 1992, a few weeks before his 17th birthday, was Julián Camilo (“Julio” in the 2011 New York Mets Media Guide). The expansion Florida Marlins, who were preparing to debut in the National League in 1993, gave Castillo $2,800 to add him to their ranks. Impulsively, he bought a moped for his family as an alternative to shabby bicycles.13 He tried to celebrate with some friends who must not have met with his mother’s approval, but that evening didn’t last as long as he’d planned. Faustina tracked the group down around midnight, lectured her son in front of the others, and then ordered him to walk back home with her.14

In 1993 Castillo didn’t need to leave the island to begin his pro career. He was assigned to Florida’s rookie-level team in the Dominican Summer League. His batting average was .282 and his on-base percentage was .368 in 69 games. He drove in 31 runs and scored 48. In 1994 he played in the States on another short-season, rookie-level team, the Gulf Coast League Marlins. His batting average dipped to .264 but he stole 31 bases in 57 games.15

For 1995 Castillo was assigned to the Class-A Kane County Cougars in Chicago’s western suburbs. The Marlins’ director of player development, John Boles, had great preseason expectations, calling Castillo the best prospect among second basemen he’d ever seen. At that point Castillo had reached his major-league height of 5-feet-11 but his weight was just 146 pounds.16 He didn’t disappoint, and was selected to the Midwest League all-star game played on June 20 in suburban Grand Rapids, Michigan.17 During a stolen-base attempt a month later he slid head-first into the knees of Fort Wayne shortstop Mike Moriarty and both players ended up on the disabled list for the remainder of the season. Castillo sustained a serious shoulder injury and Moriarty suffered a torn anterior cruciate ligament. Castillo was hitting .326 at the time.18

At the start of the 1996 season, Castillo was ranked as the Marlins’ number-two prospect by Baseball America. He started the season with the Double-A Sea Dogs in Portland, Maine. When John Boles would visit, he’d made a point of hitting groundballs to Castillo. “He didn’t do it for anyone but me,” Castillo noted. “He said, ‘Luis, if I’m going to be a manager in the big leagues, you’ll be with me right away.’ I said, ‘Thank you.’ I never think he would manage in the big leagues.”19 Castillo was named to play in the Eastern League all-star game on July 8 in Trenton, and three days later Boles was named manager of the Marlins, to finish the season started by Rene Lachemann. Less than a month later, the Marlins brought up Castillo and pitcher Felix Heredia from Portland.

Late that same day, August 8, Luis Castillo made his major-league debut at home against the Mets as the starting second baseman and leadoff hitter. He was hitless in three plate appearances before being lifted for a pinch-hitter. He saved other milestones for maximum impact the next day. Again atop the lineup versus the Mets, he singled in the fourth inning for his first major-league hit. He scored his first run that inning, and it was his team’s only one before extra innings. In the bottom of the 10th, Castillo faced Doug Henry with two outs and singled home Alex Arias from second base with the winning run. Castillo hit his first career home run before the month was over, on August 30 in Cincinnati off Mike Remlinger. All told, Castillo batted .317 in 109 games for Portland and .262 in 41 games for the Marlins.

Boles was replaced by Jim Leyland as manager of the Marlins for 1997 and Leyland chose Castillo to start at second base on Opening Day. By being paired regularly with shortstop Edgar Renteria, who was also 20 years old, Castillo became half of the youngest everyday middle-infield duo in the history of the National League.20 His highlight-reel play of the season may have come on June 10 against the Giants, when teammate Kevin Brown took a no-hitter into the seventh inning. A wire-service account of the game said the best defensive play came that inning when J.T. Snow hit a grounder behind second base and Castillo made a backhand play in order to throw Snow out at first.21 Overall, though, Castillo’s season was an unsatisfactory one, and when his batting average was only at .240 in late July, he was sent down to Triple-A Charlotte. He hit very well there, .354 in 37 games, but was not brought back up to the majors and thus didn’t play with the Marlins in the 1997 World Series. About five years later, Clark Spencer of the Miami Herald summed up what that October 26 was like for the Marlins’ Opening Day second baseman: “With a heavy heart, Luis Castillo clicked on a television that October night in 1997 and watched the Marlins win the World Series. There was his friend, Liván Hernández, hoisting the Series MVP trophy. Castillo had learned to drive using Hernández’s Land-Rover when the two were roommates in Double A the season before,” Spencer wrote. “There was his other friend, Edgar Rentería, delivering the winning hit in Game 7. He and Rentería had come up through the Marlins’ farm system together.”22 At least it turned out that there was a silver lining. Though he hadn’t played in the postseason, as an outcome of the Marlins’ championship he received $70,000. “As soon as I got that money, I told my mama, we want to get you out,” Castillo recalled. “So I bought her a house.”23

Castillo’s hot stint in Charlotte didn’t earn him a trip back to the majors at the start of 1998. Even a 32-game hitting streak from May 24 to July 3 didn’t earn him an immediate call-up by the Marlins. Still, when he had his on-base percentage at .403 in early August, with 74 runs scored in 100 games, Florida’s management could ignore him no longer. However, after returning to the majors on August 4 he just barely hit above .200 the rest of the way.

Meanwhile, Jim Leyland had gone from winning the World Series to a record of 54-108. It wasn’t his fault, because by the start of the 1998 season the ownership had traded Brown and 10 other key players, leaving their manager with the youngest squad in the majors. “Florida manager Jim Leyland must have felt like a daycare worker this year,” quipped a Florida sportswriter. “The Marlins played a major-league record 27 rookies in 1998.”24 Leyland resigned on October 1.

The collective failure of the Marlins’ younger position players in 1998 reopened a door for Castillo, and it was pushed wide open when John Boles was named to his second stint as the team’s manager. Castillo spent all of 1999 with the Marlins, and was a major-league starting second baseman for the remainder of his professional career. Castillo rewarded Boles for his faith with a .302 batting average in 128 games, and his 50 steals ranked fourth in the National League. The South Florida Chapter of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America named him the team’s MVP for the season.25

Castillo proved in 2000 that the previous season was no fluke. He achieved the highest marks of his major-league career with 101 runs scored, a batting average of .334, an on-base percentage of .418, and 62 stolen bases. The latter figure was the best in the majors and thus netted him that year’s Lou Brock Award. Interestingly, seven of those thefts came in a bunch. On May 17 against San Diego, Castillo set a club record and career high with four steals, and the next day he had three more. As a result, he fell one shy of the National League record for steals in consecutive games, which was set by Walt Wilmot of the Chicago Colts on August 6-7, 1894.26

Castillo’s attitude pleased manager Boles. After one game that season Castillo walked into his manager’s office and put a wad of cash on the desk for failing to bunt successfully. It was a payroll refund of sorts. “He was dead serious,” Boles recalled. “He was so disgusted with himself.”27

The 2001 season was Castillo’s only mediocre year as a regular for the Marlins; he batted .263. Boles was fired on May 28, although the team’s 22-26 record certainly wasn’t atrocious. There’s no indication that Castillo slumped afterward. Boles was replaced for the remainder of the season by Hall of Famer Tony Pérez, who’d been elected to Cooperstown the previous year.

It’s entirely possible that Castillo was distracted by the fact that he and his wife, Angie, were expecting their first child, who arrived shortly after the season wrapped up. Luis Angelo Castillo was born on October 12, 2001. In any event, the new father performed very well for the Marlins during the first half of 2002, despite the fact that he didn’t see Angie and the baby from the start of spring training until July 8. Castillo flew his wife and son in from the Dominican Republic for a very special occasion: He’d been named a National League All-Star for the first time, and the game was the next night.28

What really got Castillo noticed during the first half of 2002 was his 35-game hit streak, from May 8 through June 21. During that span he had 62 hits in 154 at-bats, a .403 clip. It was the longest streak since Paul Molitor of the Brewers had one of 39 games in 1987. That 1987 season Benito Santiago of the Padres had set the record for the longest streak by a Latino player at 34 games. At the time of Castillo’s accomplishment, he tied the sixth longest streak in National League history and the 10th longest overall. As of 2018 he has been surpassed and tied by two Phillies: Jimmy Rollins hit in 38 straight games across the 2005 and 2006 seasons, and Chase Utley hit in 35 straight games in 2006.

Not surprisingly, media attention intensified across the hemisphere after Castillo’s streak reached 30 games. When it reached 31, a Florida sportswriter (whose report was reprinted by a newspaper in Arizona) learned that people Castillo knew may have been bothering him more than random journalists. “The Florida Marlins second baseman normally is happy to hear from home, but lately each ring of the phone ratchets up the pressure a notch,” wrote Brian Bandell. “‘A lot of friends from the Dominican Republic call me,’” Castillo himself said. “‘I don’t like that.’”29 That’s not to say dealing with the reporters was easy, because Castillo still struggled with English when an interpreter wasn’t available. On the day he extended his streak to its maximum, a New York Times reporter noted that Castillo had asked for guidance from teammate Mike Lowell, who was born in Puerto Rico of Cuban descent. “He asks me about the media and what to say,” Lowell said. “I just tell him to say what you feel.”30

Though Castillo wouldn’t reunite with his wife and infant son for about two more weeks, on the night his streak reached 35 games he was able to celebrate with six relatives who attended that home game against the Tigers. Traveling together to the ballpark were a female cousin, two nephews, a brother-in-law, his sister Altagracia, and their mother, whose spirits weren’t undercut by the knowledge that they reached their seats (29 rows behind home plate) about an inning after Castillo extended his streak with an infield single in the bottom of the third. The family members told a reporter that although he asked his family for prayers and took figurines reflecting their Catholicism to adorn his locker – behavior consistent with the anxiety hinted at by many of his comments in the media – they instead perceived signs, mostly in his body language, that he remained confident in his abilities. But the keen interest across the baseball world didn’t mean much in that part of Florida, as only 5,865 fans were on hand.31 The turnout the next day, a Saturday, jumped to 14,713 but they saw Castillo go hitless in four plate appearances.

The Marlins honored Castillo with a special night on July 3, and 11,785 fans turned out for it. The pregame festivities included a presentation by the Dominican Consulate. Castillo in turn took advantage of the opportunity to launch the Luis Castillo Gear for Kids Fund in conjunction with the Florida Marlins Community Foundation. He got the ball rolling with a $5,000 donation but fans were asked that night – and annually while he was a Marlin – to bring donations of new or used baseball equipment to be shipped to children in the Dominican Republic.32

Six days later was the All-Star Game in Milwaukee. The fans had voted José Vidro of the Expos as the starting National League’s second baseman, and the NL manager, Bob Brenly of the Diamondbacks, had chosen Junior Spivey from his own team as a backup. Spivey replaced Vidro after three innings, and Castillo replaced Spivey after the seventh inning. As a result of the contest lasting 11 innings (at which point it was notoriously ended as a 7-7 tie) Castillo played four innings and batted twice. He flied out to center field both times. Defensively he logged three assists.

Castillo finished 2002 with a batting average of .305, and his 48 stolen bases won him his second Lou Brock Award. In addition, he was named team MVP for the second time by the South Florida Chapter of the BBWAA. On October 23 Castillo underwent arthroscopic surgery in his right hip to repair a torn labrum, but over the course of the next year there was ample reason to believe the procedure was successful.33

By the winter of 2002-2003 Castillo was a multimillionaire at 27. He had bought himself a Mercedes and wore expensive jewelry, but most of his earnings went toward relatives. His sister Maribel’s family was occupying their childhood house by then, and he paid to have rooms added, a tile floor installed, and a second story built. He did likewise to the house next door, which was their brother Julio César’s. He moved his parents and one grandmother to Santo Domingo, the capital and largest city, into a large two-story home in a middle-class neighborhood. He, Angie, and young Luis Angelo were living across town in a modest apartment near the city’s country club.34

On several fronts Castillo was at least as good in 2003 as he was the prior season. He was selected as an All-Star for the second consecutive year, this time by Dusty Baker of the Giants. He did get to play in the game again, and again went hitless in two plate appearances. He improved on his 2002 batting average somewhat at .314, and reached a career high in base hits in the process, with 187. In light of his first “glove” as a youngster, in terms of individual achievements Castillo may have been most thrilled to receive his first Rawlings Gold Glove Award. He received votes for National League Most Valuable Player, and his total ranked 21st.

The main reason to believe that Castillo’s hip surgery in October of 2002 had a lingering effect is that his stolen bases dropped from 48 in 2002 to 21 in 2003. He was caught stealing 19 times, so his success rate was barely above 50 percent. (He presumably made a necessary adjustment during 2004, when he again stole 21 bases but was caught just four times.)

On top of another admirable year individually, 2003 was the only time when Castillo played in the postseason as a Marlin. He was effective offensively in the National League Division Series against the Giants, whom the Marlins eliminated, three games to one. He batted .294 with three doubles and three walks. He didn’t bat well against the Cubs in the National League Championship Series, but on October 14 he unwittingly helped perpetuate one of the strongest supposed curses in sports history. The Cubs led the best-of-seven series three games to two and were ahead 3-0 at home with one out in the eighth inning. Castillo lofted a pitch from Mark Prior toward elevated seats along the left-field line, where the ball was deflected away from a leaping Moisés Alou by fan Steve Bartman. Given a chance to extend his plate appearance, Castillo coaxed a walk from Prior. Castillo eventually ended the inning by batting again, that time popping out to second. Between his at-bats, the Marlins scored eight times and that was pretty much the ballgame. The next night they rallied from two runs down to win 9-6 and advance to the franchise’s second World Series in its short existence.

Castillo’s hitting against the Yankees was even worse than against the Cubs. After five games the Marlins led, three games to two. The two remaining games were scheduled for Yankee Stadium, and the sixth game was the 100th World Series contest played there. Andy Pettitte and Josh Beckett each pitched shutout ball through the first four innings. Pettitte retired the first two Marlins in the top of the fifth but gave up a single to Alex Gonzalez. Juan Pierre advanced Gonzalez to second with a hit. That brought up Castillo, who was hitless in his 14 previous at-bats. Castillo was a switch-hitter and thus batted right-handed against the lefty pitcher. Pettitte’s first pitch was a called strike and Castillo swung at the second one without making contact. Castillo fouled off the next two pitches, and two more were outside the strike zone to even the count, 2-and-2. New York Times sportswriter Rafael Hermoso described well what happened next: “Castillo lined the seventh pitch to right field, sending Gonzalez, the Marlins’ previous unexpected star, chugging around the bases. Gonzalez broke from second on contact and was going to test right fielder Karim Garcia’s arm. The throw was on line. Gonzalez slid with his feet behind the plate. Catcher Jorge Posada took the throw in front of the plate and reached back with his glove. But Posada never made the tag as Gonzalez slid by the plate and dragged his left hand across the back of it. Umpire Tim Welke signaled that Gonzalez was safe, and the crowd grew quiet.”35

The Marlins scored another run, on a sacrifice fly the next inning, and Beckett shut out the Yankees, so Castillo’s timely hit was the game-winning RBI. He helped seal the deal with one out and a Yankee on first base in the bottom of the eighth inning when he fielded a grounder and tossed to Gonzalez to begin a double play.

Hermoso included quotes by Castillo about his decisive at-bat and his excitement for the Marlins as a whole, but the article led with a description of Castillo’s body language toward the end of the game: “… Castillo could not contain himself. As Josh Beckett fired his final pitches to the Yankees, trying to finish them off in the ninth inning last night, Castillo was playing deep in the dirt infield, bouncing in place like a jumping jack. … Finally Beckett tagged out Jorge Posada along the first-base line, and Castillo was freed.”36

Castillo was a free agent after the World Series, and the Mets reportedly made a strong effort to sign him. Instead, at the beginning of December he and the Marlins agreed on a deal worth $16 million over three years, less than what the Mets offered.37 Not surprisingly, his big purchase that offseason was a farm that his father, then 72 years old, had always fantasized about owning.38

That same offseason Castillo said he and fellow Dominican Moisés Alou teased each other good-naturedly about that infamous foul ball in the playoffs. “He said we were lucky,” Castillo reported. “I told him, ‘When you guys go to spring training, go early and put fans in the way and try to catch a fly ball, because maybe it can happen again.’”39

Castillo had another good year for the Marlins in 2004, with a .291 batting average. His high point for the season was likely on May 22 when he hit his only major-league grand slam, against Arizona’s Steve Sparks. It was especially significant because Castillo averaged only three homers a season. He wasn’t named an All-Star again in 2004, but he won his second consecutive Gold Glove.

In 2005 Castillo was named an All-Star again, this time by Tony La Russa of the Cardinals. He was much busier in that All-Star Game than in the other two. He replaced starting second baseman Jeff Kent in the bottom of the second inning and played the rest of the game; there was no other second baseman on the squad. In the top of the seventh inning, he got his first (and only) hit as an All-Star, a leadoff single against Kenny Rogers of the Rangers. Castillo scored when the next batter, Andruw Jones, homered. In the field he had two putouts and three assists, and helped turn a double play.

When the season ended Castillo’s batting average stood at .301, the fifth time in his seven years as a Marlins regular that he hit at least that well. He hit .423 against left-handers, the highest average against them in the NL. On April 18 against Washington, Castillo walked four times, a career high that foreshadowed an impressive mark by season’s end: He was the hardest man to strike out in the National League. He had one strikeout per 16.38 plate appearances.40 Castillo continued to excel in the field as well, and was awarded his third consecutive Gold Glove.

At the end of the 2005 season, Castillo was 29 years old and had spent a decade playing for the Marlins. On December 2 the Marlins traded him to the Minnesota Twins for two pitching prospects, Scott Tyler and Travis Bowyer. Tyler never pitched above Triple A. Bowyer was in eight games for the Twins in 2005 but never pitched an official game for any Marlins minor-league team.

When Castillo was interviewed with his new team in mid-March, he seemed genuinely content that he was no longer a Marlin. Why? He had achieved the big goal he set early on: “I would take care of my family.” And by 2006, he had. “Now everybody is happy in my family,” he said. “When I go to the Dominican Republic, I feel happy. That’s what I have been wanting to do. That’s the dream I have. That’s why I feel so good.”41

In his new league, his stats for the season didn’t look much different from his better ones with the Marlins. He hit .296, and his 25 stolen bases represented his highest total since 2002. The Twins won the Central Division so Castillo experienced the second (and final) postseason action of his career. The Twins were swept by the A’s but Castillo fared better than he did in the 2003 playoffs against the Cubs and Yankees. His batting average in the three games was .273 (3-for-11) and his on-base percentage was .429.

On July 30, 2007, after 85 games, Castillo was batting .304 for the Twins. On that day they traded him to the Mets for outfield prospect Dustin Martin and catcher Drew Butera. Castillo hit .296 for the Mets and his combined batting average for the season was .301.

The 2008 season was a disappointing one for Castillo. He played only 87 games and his batting average plunged to .245. On July 3 he was placed on the 15-day disabled list with a strained left hip flexor, and didn’t return to action until August 25.42

Castillo rebounded well in 2009. In 142 games he batted .302 and stole 20 bases. He and Angie celebrated the birth of their second child, daughter Adonai, on July 30. That day proved to be a lengthy one for her dad. He and Angie were up by 7:30 that morning, and the baby was born four minutes before noon. The Mets had a doubleheader against the Rockies, and Castillo felt he’d be letting down his teammates if he didn’t play in one of the games. They won 7-0 without him, but lost the nightcap 4-2 with him in the lineup.43

“She wanted me to stay, but I told her the situation,” Castillo said. “We had a lot of injuries, and if you can help them play better, you do it.” George Vecsey of the New York Times hinted that another part of Castillo’s motivation was to continue making amends for what Vecsey said “was probably the most egregious error in the history of the franchise, which is saying a lot. (This is coming from a writer who witnessed Marvelous Marv Throneberry.)”44

At Yankee Stadium on June 12, the Mets were ahead 8-7 going into the bottom of the ninth inning. With two outs, Derek Jeter was on second base and Mark Teixeira was on first. Alex Rodríguez hit a routine pop fly behind Castillo, who simply dropped it. Because Castillo was as surprised as everyone else, he threw to second in a vain attempt to get Rodríguez. Meanwhile Teixeira was closing in on home plate with the winning run.

“It would have been easy to hide,” Vecsey wrote. “Luis Castillo could have taken the longest shower in the history of baseball – or skulked out into the night, unshowered.”

He could have hidden, but he was very accountable,” said Alex Cora, who was playing shortstop. “There were people ready to bury him, but he handled it the right way.”45

Vecsey noted that Castillo intended to take a day off when his wife gave birth, but a rainout created the doubleheader that day. “Forty-five minutes after the delivery, he left for the ballpark and went hitless as the Mets lost, but the main thing was that he showed up,” Vecsey concluded.46

In 2010 Castillo played in 86 games for the Mets and batted only .235. He was placed on the disabled list on June 4 with a bruised right heel. He was reinstated on July 19. It was his final season with the Mets, and as something of a last hurrah he stole home in Chicago as part of a double steal on September 4. He had only two hits in 15 at-bats in that month and October. On the last day of the season, October 3, against Washington, he popped out to shortstop as a pinch-hitter.47 That was his final appearance in a professional game.

Castillo did report for spring training with the Mets in February 2011, but he frustrated Mets manager Terry Collins when he was expected to arrive early yet didn’t. It turned out that his brother, Julio César, was undergoing a serious surgical procedure. “I asked him, ‘Why didn’t you tell me?,’” Collins said of Castillo. “It certainly would have changed the way I looked at things. I hope his brother’s going to be OK.” In any event, Collins confirmed that Castillo would compete with Daniel Murphy, Brad Emaus, and Justin Turner for the starting assignment at second base.48 Turner won the starting job. The Mets released Castillo on March 18. Three days later the Phillies signed him to a minor-league deal.

Paul Hagen of the Philadelphia Daily News seemed to think that Castillo was worth giving a chance, and suggested that he was treated unfairly with New York. “For disgruntled customers in Queens to make Castillo the lightning rod for all their unhappiness about the ineffectiveness of Oliver Perez, the injuries to Carlos Beltran and Jose Reyes, the Bernie Madoff scandal and every other ill that has befallen their favorite team is obviously silly,” Hagen wrote.49

His colleague Sam Donnellon took a different view when Phillies manager Charlie Manuel expressed annoyance that Castillo was late arriving at their camp as well, writing that Castillo’s reputation was that of “a well-paid, aging star showing signs of spoil in both his game and his attitude.” The difference of opinion became moot on March 30, when the Phillies released Castillo.50

Castillo has maintained a low profile since 2011, but during the summer of 2019 he was rather suddenly implicated in Dominican drug trafficking. However, he was cleared of involvement after little more than a week.51 As an example of him choosing the limelight after his retirement, for the 2017 All-Star Futures Game in Miami he was the bench coach for the World Team, managed by former teammate Edgar Renteria.52 Later that year he was inducted into the Dominican Republic Sport Hall of Fame.53 That 14-year-old kid in San Pedro de Macorís who could barely see himself as a major leaguer someday surely had no dreams of being honored at a ceremony like a hall of fame induction.

Last revised: October 29, 2022

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author relied on Baseball-Reference.com for baseball data.

Notes

1 Phil Kimmel, foxsports.com/mlb/story/miami-marlins-whose-number-should-be-the-first-retired-040717, June 30, 2017.

2 Kevin Baxter, “Motherly Love,” Miami Herald, February 23, 2003: 1C.

3 Dave George, “Family Late, But Happy,” Palm Beach Post (West Palm Beach, Florida), June 22, 2002: 1C.

4 Mark Long, “From Milk Cartons to Majors,” Los Angeles Times, June 11, 2000: D1.

5 La Velle E. Neal III, “Castillo Still Hungers to Win,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, June 22, 2007: 1C.

6 Neal.

7 Baxter.

8 Joe Capozzi, “Castillo Gives Dreams to Dominican Kids,” Palm Beach Post, August 14, 2005: 7B.

9 Baxter. Rodríguez also coached Luis Mercedes, Guillermo Mota, Manny Alexander, and José Cano as youngsters.

10 Neal.

11 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 47.

12 Baxter.

13 Dave Hyde, “Luis’ Heart 2nd to None,” South Florida Sun-Sentinel (Fort Lauderdale), March 29, 2004: 13C. “He didn’t drive a car until 19, when his good friend and then-agent Andy Mota rented one for him to try,” Hyde added.

14 Baxter.

15 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 47.

16 Bryan Byrnes, “Young Cougars Don’t Lack Talent,” Daily Herald (Arlington Heights, Illinois), April 5, 1995: section 2, page 11.

17 2011 New York Mets Media Guide: 46. In contrast to his 1995 weight, on page 44 his weight was listed as 191 pounds.

18 Bryan Byrnes, “Kane County Experiencing Power Shortage in Dismal Second Half,” Daily Herald, July 25, 1995: section 2, 2.

19 Neal.

20 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 46.

21 “Marlins’ Kevin Brown No-Hits San Francisco Giants,” Guantánamo Bay (Cuba) Gazette, June 13, 1997: 11.

22 Clark Spencer, “Hitting It Big,” Miami Herald, July 9, 2002: 1D.

23 Jim Souhan, “Hard Times Make Twins’ Castillo Thankful,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, March 19, 2006: 1C.

24 Ken McVay, “On Second Thought,” News Herald (Panama City, Florida), October 2, 1998: 1B.

25 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 46-47.

26 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 47.

27 Neal.

28 Dave George, “Castillo Glad to Be Reunited with Wife, Son,” Palm Beach Post, July 9, 2002: 3C. His son’s date of birth is from the 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 44.

29 Brian Bandell, “The Buzz Grows as Castillo’s Streak Hits 31,” Prescott (Arizona) Daily Courier, June 18, 2002: 7A.

30 Charlie Nobles, “Castillo Keeps Hitting, Passing Hornsby’s Run,” New York Times, June 21, 2002: D5.

31 George, “Family Late, But Happy.”

32 “South Florida Honors Luis Castillo,” Palm Beach Post, July 3, 2002: 8C (a half-page ad). A Marlins press release dated September 23, 2003, posted at marlinsbaseball.com/topic/4451-marlins-press-release/, confirmed Castillo’s initial monetary donation. The team’s 2005 calendar, at miami.marlins.mlb.com/mia/community/calendar_archive_05.jsp, included the 4th Annual Luis’ Gear for Kids Day on August 14.

33 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 46-47.

34 Baxter. In this 2003 article Angie was referred to as Castillo’s fiancée, but in Dave George’s July 9, 2002, article she was called his wife, as she was in 2004 and 2009 articles cited herein.

35 Rafael Hermoso, “Castillo Rewards Marlins’ Faith with Timely Hitting,” New York Times, October 26, 2003: section 8, page 2.

36 Hermoso.

37 “D’backs Acquire Sexson in 9-Player Deal with Brewers,” Daily Herald (Arlington Heights, Illinois), December 2, 2003: section 2, page 2.

38 Hyde.

39 “Castillo Trades Barbs with Chicago’s Alou,” Johnstown (Pennsylvania) Tribune Democrat, February 26, 2004: B4.

40 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 45.

41 Souhan.

42 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 45.

43 Michael Obernauer, “Oh Baby! Castillo Makes It to Flushing for Nightcap,” New York Daily News, July 31, 2009: 75.

44 George Vecsey, “Yes, Luis Castillo Is Still with the Mets,” New York Times, March 3, 2010: B13.

45 Vecsey.

46 Vecsey.

47 2011 New York Mets Media Guide, 44.

48 “Castillo Arrives in Mets’ Camp,” Palm Beach Post, February 21, 2011: 4C.

49 Paul Hagen, “Luis Castillo Gets Audition with Phillies Just in Case Scouts Are Wrong,” Philadelphia Daily News, March 22, 2011: 48.

50 Sam Donnellon, “This Just in: Luis Castillo Is an Issue,” Philadelphia Daily News, March 23, 2011: 71.

51 Colin Dwyer, “Ex-MLB Players Octavio Dotel, Luis Castillo Cleared Of Drug Ring Allegations,” National Public Radio, August 30, 2019, https://www.npr.org/2019/08/30/755971282/ex-mlb-players-octavio-dotel-luis-castillo-cleared-of-drug-ring-allegations.

52 Jonathan Mayo, “Rosters Set for Futures Game,” MLB.com, June 29, 2017; mlb.com/news/2017-mlb-futures-game-features-top-prospects/c-239464456.

53 “Inmortalizan a Varios al Pabellón de la Fama del Deporte Rep. Dom.,” El Nuevo Diario (Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic), October 17, 2017: 31.

Full Name

Luis Antonio Castillo Donato

Born

September 12, 1975 at San Pedro de Macoris, San Pedro de Macoris (D.R.)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.