Walt Wilmot

Timing is everything. Walter Wilmot was a highly sought-after outfielder in his prime during the bidding war between the upstart Players League and the established National League. During a six-season run (1890-1895) with the Chicago Colts (the former nickname, White Stockings, was still sometimes used), Wilmot was reportedly paid an “astounding” $4,250 a season, the highest salary of any NL player, and far more than that of his more famous teammate, Adrian “Cap” Anson.1 Colts President A.G. Spalding once turned down an offer from Frank Selee of the Boston Nationals to purchase Wilmot, offering a three-year contract of $3,450 a season, “an offer that fairly astounded the baseball public at the time.”2

Timing is everything. Walter Wilmot was a highly sought-after outfielder in his prime during the bidding war between the upstart Players League and the established National League. During a six-season run (1890-1895) with the Chicago Colts (the former nickname, White Stockings, was still sometimes used), Wilmot was reportedly paid an “astounding” $4,250 a season, the highest salary of any NL player, and far more than that of his more famous teammate, Adrian “Cap” Anson.1 Colts President A.G. Spalding once turned down an offer from Frank Selee of the Boston Nationals to purchase Wilmot, offering a three-year contract of $3,450 a season, “an offer that fairly astounded the baseball public at the time.”2

Wilmot had a fine 10-year major-league career and after retiring as an active player, he stayed in baseball as a minor-league manager and team owner for many years. His salary record has obviously been shattered by modern players, but Wilmot set three rather obscure records that have never been broken. On September 20, 1890, he was hit twice in the same game by batted balls while running the bases. The next year, on August 22, 1891, he drew six walks in a nine-inning game; only one other player, Jimmie Foxx in 1938, has equaled that feat. Finally, in August 1894, Wilmot stole eight bases in two consecutive games. Rickey Henderson stole seven bases in two games, but no one has ever tied or broken Wilmot’s mark.

Walter Robert Wilmot was born on October 18, 1863, in Plover, Wisconsin, a small town in the central part of the state adjacent to Stevens Point. (Plover was later incorporated into Stevens Point.) His parents were Acel Wilmot, originally from New York, and Hannah (Morrison) Wilmot, a native of Indiana. Acel supported the family as a butcher but when he was younger served in the Union Army in the Civil War and worked as a riverboat pilot. Walter was the oldest of four children; sisters Sibyl and Bessie and a brother, John, followed him.

While Walter was in his teens, the family moved to Ada, Minnesota, where his father ran the city’s first meat market. At the time of the 1880 US Census, Walter worked as a teamster, but turned to baseball shortly thereafter; in 1881 he reportedly helped the Ada team win the amateur championship of the Northwest.3 The next two years Wilmot was a member of the semipro Grand Forks (North Dakota) Red Caps. The following year, 1884, he had a tryout with the St. Paul Apostles of the Western League but was released in April.

Later that year Wilmot’s family moved to North Dakota, and he spent at least part of 1884 with a club in Valley City. Apparently, he was a pitcher of some ability early in his career: A report noted, “During the seventh inning the catcher of the Valley City nine, Mr. Kelley, received a ‘pea warmer’ in the stomach delivered from pitcher Wilmot when Frazee was at bat. The blow doubled Kelly up for a few minutes, but he soon recovered himself sufficiently to receive the cannon shot[-]like balls that were constantly arriving from Wilmot.”4

Wilmot’s whereabouts in 1885 are not certain. He may have played part of the season in Hamilton, Ontario,5 and it’s possible that he made a brief appearance with a team closer to home in Stillwater, Minnesota, in September of that year. He began his professional career with the St. Paul Freezes of the Northwestern League in 1886 and the following year (1887) returned to the team (which had changed its name to the Saints) and had an excellent season, batting .344 in 119 games. Several sources suggested that he made have also played briefly for Oshkosh, Wisconsin,6 in the same league, but no information could be found to verify that claim.

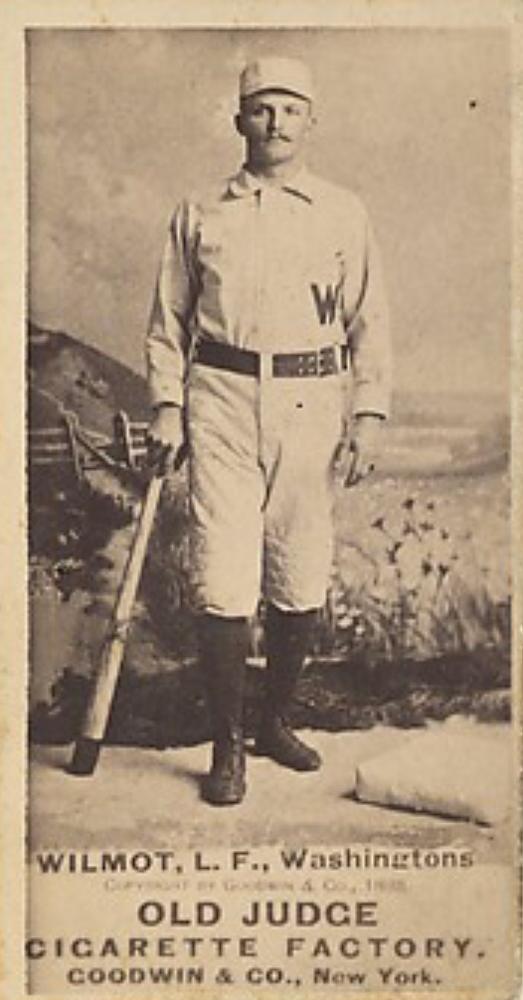

Several major-league clubs were after Wilmot’s services but it was Washington Nationals owner Ted Sullivan who went to St. Paul and secured his name on a contract calling for a salary of $1,700 per year.7 Wilmot opened the 1888 season as the Nationals’ starting left fielder and went hitless in four at-bats in his major-league debut on April 20 against the Giants at Swampoodle Grounds in Washington. He hit just .224 in his rookie season but displayed outstanding speed in the outfield and on the basepaths, swiping 46 bases. The 5-foot-9-inch, 165-pound switch-hitter returned to the Nationals in 1889 and increased his batting average to .289 while pacing the National League with 19 triples.

John Montgomery Ward was the driving force behind baseball’s first players union, the Brotherhood of Professional Baseball Players, formed in November 1889, and the Players’ League, which operated during the 1890 season. Wilmot was a member of the Brotherhood and although he likely listened to offers, had no intention of jumping to the Players’ League. He did express his desire to leave Washington and no doubt used these developments as leverage in contract negotiations.

Chicago’s Spalding was faced with the defection of many of his top players to the Players’ League, so on November 25, 1889, he purchased Wilmot’s contract from the Nationals for $4,250.8 A week later Chicago manager Cap Anson came to St. Paul, where Wilmot had made his offseason home working as a banker, and signed him to a three-year contract at $4,000 a year,9 10 making him one of the highest paid players in baseball.11 The only clause Wilmot asked for in his contract was an assurance that he would not be released if the Chicago players who signed on with the Players’ League later returned to the club.12 With the Colts in 1890, Wilmot’s 13 home runs tied for the league lead with Mike Tiernan of New York and Oyster Burns of the Brooklyn Bridegrooms. In addition, he led the league in games played and games as an outfielder (139), and in putouts as an outfielder (320).

Around this time Wilmot began to engage in other sporting interests in which he may have been more proficient than he was as a baseball player. He was an expert trap shooter and made several offseason trips to northern Minnesota and North Dakota with Anson to hunt geese, ducks, and deer. He once bought a racehorse and became widely known as one of the best billiards players in the Midwest, winning several tournaments.

Wilmot’s batting average slipped to .216 in 1892, and, with his initial three-year contract set to expire, Chicago President and part-owner James Hart planned to cut Wilmot’s salary. Wilmot threatened to retire and used his offseason employment in a lucrative brokerage business in St. Paul as a “lever to gain his end.”13 He sat out all of spring training but after pleas from Anson finally signed and joined the club in late May.

The figure for which Wilmot eventually signed was not reported. He rebounded in 1893, batting .301 in 94 games. Wilmot’s best year in the big leagues was 1894. Usually hitting third in the Colts lineup behind shortstop Bill Dahlen and ahead of cleanup hitter Anson, Wilmot batted a career-high .329 and his 45 doubles were third best in the National League. He scored 136 runs and knocked in 130 runs, good for fifth in the NL behind league leader Sam Thompson of the Phillies. His 76 stolen bases were third in the league behind Billy Hamilton.

Wilmot’s most memorable day that season was probably Sunday, August 5, when a near-capacity crowd of 9,000 was on hand at the West Side Grounds to watch the Colts take on the Cincinnati Reds. In the top of the seventh, with Chicago leading 8-1, a cigar dropped carelessly on the wooden roof of a tool shed under the seats caused a fire to break out in the “northwest corner of the 50-cent section.” Soon flames and smoke blocked the stairway exit, leaving the only choice for fans to go onto the field to escape the blaze. However, a wire screen with barbed wire blocked their path. When they realized the danger, Wilmot and outfielder Jimmy Ryan grabbed bats and began beating down the fence to allow the frightened spectators to escape. More than 200 fans were trampled, burned, or cut on the fence, but because of Ryan and Wilmot’s heroic action, there were no fatalities.14

The Western League was reorganized in 1894 under Ban Johnson. Wilmot attended the Western League meeting in the fall of 1894 to try to secure a franchise for St. Paul. But with backing from John T. Brush, the franchise was instead awarded to Charles Comiskey. Rebuffed in his first attempt at team ownership, Wilmot returned to Chicago for the 1895 season, which would turn out to be his last with the Colts. He had another strong year, batting .283 in 108 games.

Throughout his career, several game accounts mentioned Wilmot’s outstanding speed in the outfield, but other reports frequently noted a “fumble” or “rank muff” on the part of Wilmot that led to runs by the opposition. Despite his range, his defensive statistics were poor, even for the era. Twice he led the National League in errors by an outfielder, and in 958 career outfield games, 745 of them in left field, Wilmot committed 228 errors for a rather dismal .903 fielding average.

Part of the explanation may have been that left field in Chicago was the sun field. Wilmot dropped numerous fly balls when the sun got in his eyes while he tried to make a catch, bringing on abuse from fans in the left-field bleachers. The heckling reached a breaking point one day in 1895 when “Walter Wilmot, supported by half the team and several Cleveland payers, went into the 25-cent bleachers in left field and administered a well-deserved thrashing to an abusive individual whose vile tongue has caused the players and crowds great annoyance lately. The party was located, and besides being well punched, was thrown out of the grounds.”15

In 1896 Anson loaned Wilmot to Minneapolis of the Western League, where he signed as player-manager. Employing many of disciplinary methods he had learned from Anson, Wilmot piloted the Millers to an 89-47 record and the league pennant. Bill Hutchison, a former teammate in Chicago, won 38 games and Wilmot batted .391 as the team’s left fielder. Many of the team’s stars, including slugging first baseman Perry Werden, were signed by major-league clubs and the team plummeted to the second division in 1897, prompting its owners to release Wilmot in July.

Wilmot was indirectly responsible for the early success of pitcher Deacon Phillippe. In 1897 Wilmot partnered with Anson to form a four-team semipro league in North Dakota that served as a quasi-farm system for both the Millers and Chicago. Phillippe was the most notable player sent to Fargo by Minneapolis to gain experience. He was later drafted by Louisville and then moved to Pittsburgh when the National League contracted in 1900. Phillippe is best remembered as the winning pitcher in the first modern World Series game in 1903.

Initially there were rumors of Wilmot joining Connie Mack in Milwaukee in 1897 but instead he returned to the major leagues, signing with the New York Giants for the balance of the season. He was back with the Giants in 1898 but, slowed by a sore arm and weak batting, was released in June.16 This concluded Wilmot’s major-league career. He appeared in 962 games over 10 seasons and finished with a batting average of .276. Among his 1,100 hits were 152 doubles, 92 triples, and 58 home runs – a considerable total in the nineteenth century. He drew 350 walks and struck out just 233 times. Wilmot stole 383 bases in the major leagues, and 76 in a season twice (1890 and 1894). His 1890 total was the fourth best in the league behind leader Billy Hamilton of Philadelphia, who swiped 104.

After this release by the Giants Wilmot returned to Minneapolis, where he managed the team and continued to play the outfield through the 1900 season. In February 1901 Wilmot signed to manage Milwaukee of the American League but when the club owners would not concede control over player acquisition that Wilmot thought necessary to field a winning team, he withdrew and became a team owner for the first time when he was awarded the Louisville franchise in the new Western Association (formerly the Interstate League).17 Wilmot had his team playing winning baseball, but poor attendance prompted him to transfer the team to Grand Rapids, Michigan, in June. He batted .311 as a regular outfielder and managed the club to a first-place finish.18

A baseball war dominated in Organized Baseball during first years of the twentieth century, resulting in multiple franchise shifts and changes in league affiliation. Wilmot’s former team, the Minneapolis Millers, had been longtime members of first the Western Association, then the Western League, and then the minor American League through 1900. When the American League declared itself a major league prior to the 1901 season, replacing four teams, Minneapolis was one of the franchises left behind. But a new minor league, the American Association, was formed in 1902 and Wilmot bought the Minneapolis franchise.19

The Millers finished in seventh place, 43½ games out, and after they lost their first 11 games of the 1903 season, Wilmot resigned as manager in early May. His threat to “quit baseball for good” lasted only a couple of weeks until in late May he was signed as manager and part-owner the Butte (Montana) Miners. He led the club to the Pacific National League pennant. The following year the Miners got off to a slow start, attendance suffered, and when club began to face financial difficulties, Wilmot began to sell off his best players. The following year he sold his interest in the club and eventually returned to Minneapolis.

Now over 40 years old, Wilmot was finally done as an active player. But he wasn’t done with baseball. He signed to coach the University of Minnesota baseball team for three seasons (1908-1910) and opened a billiard parlor at the Nicollet Hotel in Minneapolis. Over the last two decades of his life, Wilmot listed his occupation in city directories and on census forms as either a promoter or manager. Most notably, he staged large events for the Minnesota Automobile Show Association, where a former player of his, Perry Werden, worked as his assistant. Over the years he branched out, serving as superintendent of an automobile exhibit at the Michigan State Fair, and he promoted other events like wrestling matches and an aviation meet in the Twin Cities.

Wilmot married three times. In November 1883 he married a woman in Menominee, Wisconsin, but that union was short-lived. A few months after the wedding Mrs. Wilmot “ran away to Spokane Falls with a traveling man.”20 Wilmot was granted a divorce on grounds of desertion. On November 7, 1900, he married Claire Macdonald in Kansas City. She was the daughter of a judge and congressman who had recently moved to Kansas City from Minnesota. Wilmot met Claire when they both were living in Minneapolis and they had a son, John, born July 25, 1902, in Minneapolis. A second, son, Walter Robert Jr., was born on June 25, 1904, in Butte while Wilmot was managing there.

The circumstances surrounding Wilmot’s third marriage are a bit confusing. He is listed in Minneapolis city directories in 1908 and 1909 but at the time of the 1910 US Census, he, Claire, and their sons were living with his mother-in-law in Kansas City, and he listed his occupation as that of a land promoter. The couple are shown living at the same address in 1912 and 1913 Kansas City directories but apparently divorced around that time as there is a record of a marriage between a Walter Wilmot and a Gladys Packard on March 3, 1913, in Indiana.

The 1920 US Census lists Walter and Gladys as living in Minneapolis with son Walter Jr. (Walter and Claire’s first son, John, died accidentally in 1917), and 1920, 1921, and 1922 city directories list Mrs. Claire M. Wilmot and Walter R. Wilmot living at separate addresses in Minneapolis. Claire is listed as Walter’s spouse in his Find-a-Grave entry, but Illinois death records list his spouse as Gladys. Several of his obituary notices mention being survived by his widow. No first name of the widow is given, but they mention that he was also survived by Walter, a “son by a previous marriage,”21 implying that the widow was not his mother (Claire).

It is not known what malady Wilmot suffered, but he went to Chicago in the fall of 1928 for treatment by medical specialists. After what was described only as a “lingering illness,” Wilmot died at a sanitarium in Chicago on February 1, 1929, at the age of 65. A Presbyterian funeral service was held at Arnett Chapel in Chicago and his body was returned to Stevens Point, where he was interred in the family plot the following spring. He was survived by his wife and son.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Len Levin and fact-checked by Kevin Larkin.

Sources

Unless otherwise noted, statistics from Wilmot’s playing career are taken from Baseball-Reference.com and genealogical and family history was obtained from Ancestry.com.

The author also used information from Wilmot’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Notes

1 “Funeral Rites for Wilmot to Be Held Sunday,” Minneapolis Tribune, February 2, 1929: 5.

2 “W.R. Wilmot, Once Pilot of Millers, Dies,” Minneapolis Tribune, February 2, 1929: 1.

3 “Bring Body of Wilmot for Burial,” Stevens Point (Wisconsin) Journal, February 4, 1929: 2.

4 “The Base Ball Game,” Jamestown (North Dakota) Weekly Alert, August 8, 1884: 2.

5 “W.R. Wilmot, Once Pilot of Millers, Dies.”

6 “Wilmot’s Pay Best of 90s Topped Anson,” Stevens Point Journal, February 2, 1929: 6.

7 “Wilmot Goes to Washington,” St. Paul Globe, October 20, 1887: 1.

8 “Wilmot Was Dominating Figure in 19th Century,” Portage County Gazette (Stevens Point, Wisconsin), July 20, 2001: 12.

9 “Wilmot Gets $4,000 a Year, “Washington Evening Star, December 2, 1889: 5.

10 Other sources report his annual salary at $4,250. Stew Thornley, On to Nicollet: The Glory and Fame of the Minneapolis Milers (Minneapolis: Nodin Press, 1988), 21; “Bring Body of Wilmot for Burial,” Stevens Point Journal, February 4, 1929: 2.

11 Michael Haupert, “MLB’s Annual Salary Leaders Since 1874,” https://sabr.org/research/article/mlbs-annual-salary-leaders-since-1874/.

12 “Adrian C. Anson Pleased with His New Man,” St. Paul Globe, December 8, 1889: 7.

13 “Wilmot Will Retire,” Chicago Tribune, March 5, 1893: 7.

14 “Hurt in a Panic,” Chicago Record, August 6, 1894: 1-2.

15 Minneapolis Tribune, August 25, 1895: 1.

16 “Walter Wilmot Released,” St. Paul Globe, June 9, 1898: 5.

17 “Wilmot Gets a Franchise,” Minneapolis Journal, March 30, 1901: 10.

18 Grand Rapids finished with the best record in the Western Association, but at a year-end league meeting, several of its wins were thrown out and Dayton was awarded the league pennant.

19 “Wilmot, Head Miller,” Minneapolis Journal, December 24, 1901: 7.

20 “Fielder Wilmot Wants a Divorce,” Chicago Tribune, March 1, 1891: 3.

21 Walter Wilmot Rites Held in Chicago Chapel,” Minneapolis Tribune, February 4, 1929: 10.

Full Name

Walter Robert Wilmot

Born

October 18, 1863 at Plover, WI (USA)

Died

February 1, 1929 at Chicago, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.