Bill Denehy

“He’s a heck of a guy. He’s enthusiastic and great for the (University of Hartford) program. He’s the reason why a lot of us are here. He is a man with big dreams. His dreams became our dreams. We believed in him.” — University of Hartford player Brian Crowley in the aftermath of Bill Denehy’s termination as head baseball coach at the University of Hartford in 1987.1

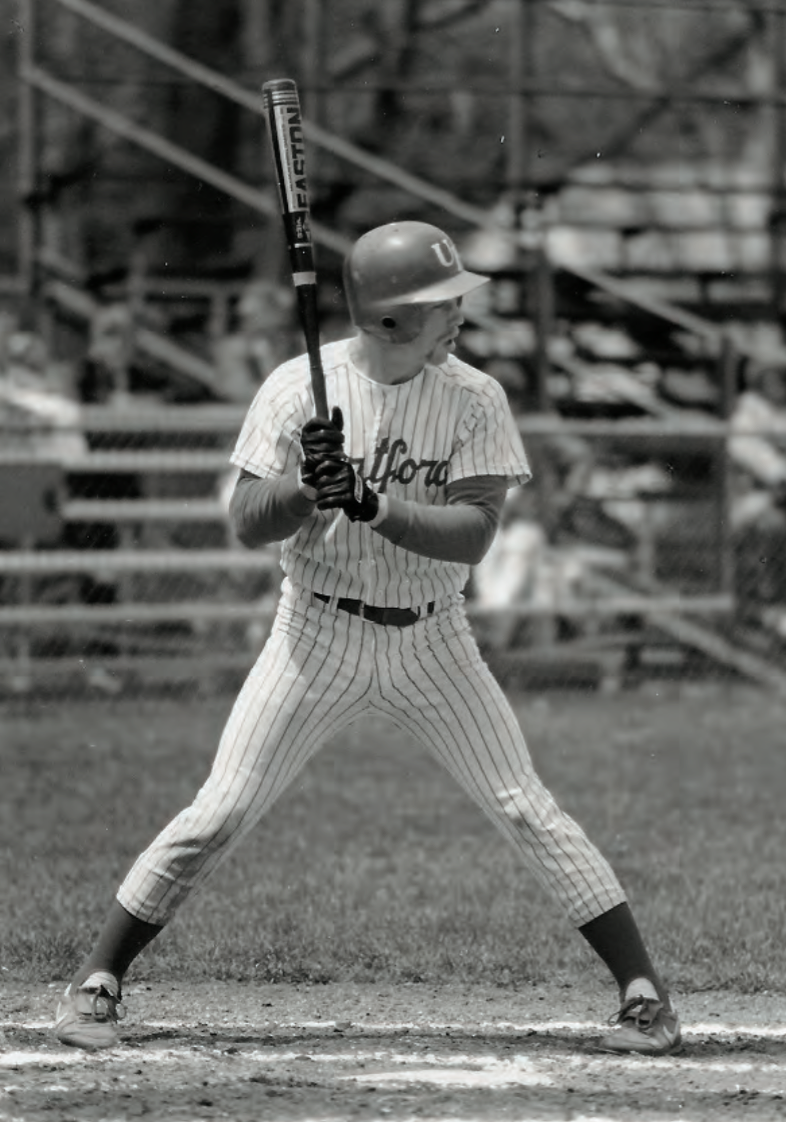

“He got me to spread my feet farther apart and moved my hands into my body. It shortened my swing and got me on the ball better.” — University of Hartford player Jeff Bagwell in 1989.2

This is a story about a man whose talent was unfortunately compromised by equal doses of rage and addiction. Along the way there were moments of exhilarating success accompanied by episodes of debilitating pain. His moment in the sun has become a time of darkness as he enters old age. And it is the story of some enduring friendships.

This is a story about a man whose talent was unfortunately compromised by equal doses of rage and addiction. Along the way there were moments of exhilarating success accompanied by episodes of debilitating pain. His moment in the sun has become a time of darkness as he enters old age. And it is the story of some enduring friendships.

Bill Denehy never knew his paternal grandfather, James Denehy, but his grandmother, Anne Frances Denehy, related that grandpa was prone to display his temper. Bill Denehy, like his grandfather, had his moments of anger, including an early one that caused him to be kicked off his high-school baseball team in his junior year.

William Francis Denehy was born on March 31, 1946, in Middletown, Connecticut, the only child of Frank “Stretch” Denehy and Anna Zawisa Denehy. Bill’s father had been born Francis Joseph Denehy on April 11, 1912, and died on April 11, 1996. He was director of shipping at International Silver.3 As with many of his generation, baseball started in Little League and Bill, in 1958, pitched his Moose Little League All-Stars to the District Nine Little League title.4

He pitched for his high-school varsity team beginning in his sophomore year, but his control was nonexistent. In his junior year, after he purposely hit a batter, his coach, Gene Pehota, dropped him from the squad. Nevertheless, scouts had begun to take notice. One scout, Bots Nekola of the Boston Red Sox, counseled Denehy in 1963 and urged him to change his delivery from directly overhand to three-quarters.

With the new delivery, Denehy resurfaced that summer in American Legion ball, hurling two no-hitters. In the second, on July 10, he struck out 16 in the seven-inning game, and the only batter to reach base safely did so when he was hit by a pitch.5 Bill starred in basketball and baseball at Woodrow Wilson High School in Middletown and was named to the Middletown Press All-Star basketball team in his junior year. He had dreams of going to St. Bonaventure to play basketball and baseball. However, St. Bonaventure discontinued its baseball program, and Denehy concentrated on the sport, especially after success he had enjoyed in the summer of 1963. In his final basketball game with Woodrow Wilson, he scored 18 points as his team fell to Middletown, 48-38, in an early-round game in the State Class B tournament.6

Denehy reverted to his old overhand style the following spring and led his baseball team to the 1964 Class B championship. Although the team was rated only 15th in its division, it had won its last four conference games before the state tournament and raced through the tournament. During the season, Denehy won his last eight decisions after being the tough-luck loser in two early-season starts. He struck out 10 batters or more seven times.7

His season had several highlights. In a 2-1 14-inning win over cross-town rival Middletown at Palmer Field in front of 1,500 fans on May 30, “Baseball Bill” pitched all 14 innings, striking out 23 batters. The large crowd was there because the game was a benefit for Denehy’s basketball teammate Stan Kosloski, who had suffered severe back injuries in a traffic accident on February 24, 1963.8 In the semifinals of the state tournament on June 10, Denehy was matched up against John Lamb of Housatonic Regional. Through the regulation seven innings, the game was scoreless and Denehy had not allowed a hit. He allowed a hit in the eighth inning, but the game remained scoreless until the 11th inning, when Woodrow Wilson pushed across three runs to win the game.9 Lamb went on to pitch parts of three seasons with the Pittsburgh Pirates. In the championship game on June 15, 1964, Denehy pitched his team to the title with a three-hitter, striking out 10, and hitting a triple in the 8-1 win over Seymour High School.10

Denehy graduated from high school on June 17, 1964, and pitched American Legion ball again that summer. His Middletown Post 75, with his father, Stretch, then 52, as the assistant coach, dominated its zone, going 16-1, and went on to compete in the state championship tournament. The team fell one game short of qualifying for the championship game; it was eliminated from the tournament on August 8.11 During the regular season, on July 5, he struck out 26 Niantic batters in a 15-inning game, winning, 1-0.12 By the end of the August, Denehy was sought by each major-league club, and it came down to a choice between the Red Sox, the Yankees, and the Mets, all of whom were offering modest bonuses. He signed with Mets scout Len Zanke on September 8, 1964, for a package in the range of $20,000, and because he felt there was more of an opportunity to move up quickly in the organization. Denehy was assigned in the fall to the Mets team in the Florida Instructional League, The Mets director of player development, Eddie Stanky, looked at Denehy’s 220-pound frame and told him that losing weight was a must. Denehy dropped 20 pounds, appeared in 11 games (five starts), and went 2-3 with a 2.91 ERA.

In his first full season in the minors, Denehy played with Auburn, the Mets’ Class-A affiliate in the New York Penn League. He was an all-star selection, tying for the team lead in wins with 13 and leading the team with 10 complete games. He led the starters with a 2.78 ERA. He pitched a team-leading 194 innings as Auburn under manager Clyde McCullough finished second in the six-team league with a 73-55 record. McCullough praised the youngster, saying, “Denehy’s a real hustler. Of the six games he’s lost (through August 10), he’s been in all the way. Binghamton beat him the other night, 2-0, on two unearned runs. It was the best game he’s pitched all year. … He’s a thinking pitcher, not a thrower.”13

With the escalation of the war in Vietnam, Denehy joined the National Guard in the fall of 1965 and spent four months at Fort Dix, New Jersey, getting out of basic training just in time to report to spring training with the Mets in 1966.14

At the beginning of the 1966 season, Denehy was promoted to Williamsport of the Double-A Eastern League and his success continued. Playing for Bill Virdon, he went 9-2 to post the highest winning percentage on the team (.818) and led the starters with a 1.97 ERA. In early July, when his record at Williamsport was 7-2, he was promoted to Triple A but did not perform well at Jacksonville in 10 appearances (0-4, 6.30 ERA). He was sent back to Williamsport on August 13 and won his final two decisions of the season. He was sent to the Instructional League at season’s end. Among those giving him instruction was Mets special field assistant Whitey Herzog. Denehy went 2-2 with a 2.50 ERA in 10 appearances.

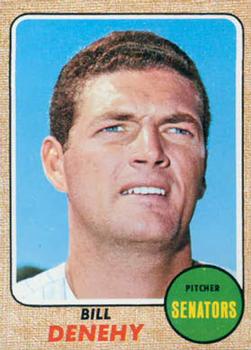

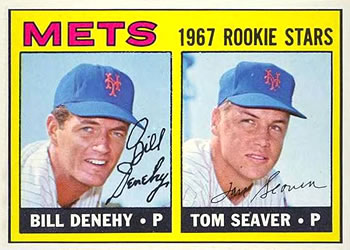

In spring training in 1967, there were raves about Denehy and it appeared that he would be destined for long relief in the Mets bullpen in 1967. Under the tutelage of pitching coach Harvey Haddix, he changed his grip with positive results. Joe Donnelly of Newsday observed, “[H]is fastball takes off and his curve dives. They come out of a tangle that straightens six feet four inches and 200 pounds, delivered in the classic overhand manner.”15 Denehy had struck out 20 batters in 20 spring innings, and his ERA for the spring was 0.53.When Topps issued its set of cards for the season, his picture was on a card titled “Mets 1967 Rookie Stars.” His picture was on the left. In the picture on the right side of the card was Tom Seaver. Bill Denehy’s rookie card has grown in value over the years.

In spring training in 1967, there were raves about Denehy and it appeared that he would be destined for long relief in the Mets bullpen in 1967. Under the tutelage of pitching coach Harvey Haddix, he changed his grip with positive results. Joe Donnelly of Newsday observed, “[H]is fastball takes off and his curve dives. They come out of a tangle that straightens six feet four inches and 200 pounds, delivered in the classic overhand manner.”15 Denehy had struck out 20 batters in 20 spring innings, and his ERA for the spring was 0.53.When Topps issued its set of cards for the season, his picture was on a card titled “Mets 1967 Rookie Stars.” His picture was on the left. In the picture on the right side of the card was Tom Seaver. Bill Denehy’s rookie card has grown in value over the years.

Denehy had earned a spot as the fifth man in the Mets five-man pitching rotation. His first appearance came in the Mets’ fifth game of the season, on April 16 in Philadelphia. There was only one bat in the lineup that worried Denehy — the same bat that worried every other pitcher in the National League not wearing a Philadelphia uniform. Dick Allen was called Richie Allen in those days and, in his first two at-bats did not see anything resembling a strike from Denehy. In the fifth inning, after a walk to Dick Groat, Allen stepped in. Denehy’s first pitch was high and tight for ball one. The second pitch was a slider, low and away, but it was tailing back toward the batter as it reached home plate. Allen swung, and the ball headed to deep left-center field, where it was intercepted in flight by a Coca-Cola sign atop the left-field roof, above the 357-foot sign.16 The two-run homer was all the Phillies would need. The Mets were unable to put any runs on the board. When Denehy left the game with one out in the seventh inning, he had eight strikeouts to his credit. The Mets lost the game, 2-0, and Denehy’s first career decision was a loss. After the game, Groat said, “We won, he lost, but that could be quite a kid.”17 The eight strikeouts tied the franchise record for a debut, equaling the total collected by Tom Seaver only three days earlier. That mark would hold for 45 years, until Matt Harvey fanned 11 in his debut with the Mets on July 26, 2012.

Denehy was fully entitled to file suit against his mates for lack of support during his first four starts. In his second start and first appearance in front of a home crowd, Denehy allowed three runs in eight innings. He was victimized once again by the home-run ball. He yielded a solo homer to Tony Gonzalez in the second inning and after the Mets tied the score in the bottom of the inning, the Phillies manufactured a run on three singles (two of them bunts) in the fourth to take a lead they would not relinquish. An eighth-inning homer by Allen was the stuff of legend. Newsday’s Steve Jacobson wrote, “Allen hit it over the fence, over the grass behind the fence, and onto the path where the buses park.”18 Denehy had become the first pitcher in the Mets’ six-year history to lose his first two major-league starts despite quality outings. The Mets managed one hit off Cincinnati’s Gerry Arrigo in Denehy’s third start, and three errors led to only two of the six runs he allowed being earned. After the 7-0 loss to the Reds, he was 0-3.

“It was like that one bad breakup in your lifetime you don’t ever get over.”

– (Daughter) Kristin Denehy April 200519

Start four was against San Francisco’s Juan Marichal, who had never lost to the Mets in 17 decisions.20 Before the game, Denehy was given a “black beauty” by a teammate. It was an amphetamine said to add three feet to a pitcher’s fastball. Whether or not it was due to the amphetamine, Denehy threw in pain from that day forward. In the fourth inning he began to feel intense pain in his shoulder, particularly after throwing a hard slider21 and walking Willie Mays (whom he had struck out in the first inning) with two outs and none on. He then loaded the bases before yielding a two-run double to Hal Lanier. Denehy escaped the inning without further damage but the two runs in four innings resulted in his being tagged with his fourth loss. The Giants extended their lead after Denehy left and won, 8-0. In Denehy’s first four starts, the Mets lost by a cumulative score of 20-1.

After a stint on the disabled list, the first of many cortisone shorts, and a couple of relief outings, Denehy took the mound at Shea Stadium in the first game of a doubleheader on May 28 in front of 48,548, the largest crowd of the young season. The Mets were facing the Atlanta Braves and Denehy for the first time had run support, principally from Tommy Davis, who had a career day with 5 RBIs. He banged out a first-inning three-run homer, hit an RBI single in the third, and had RBI doubles in the fifth and seventh. Denehy was victimized by a two-run shot by Clete Boyer and a solo shot by Joe Torre but was leading 5-3 when he left the game with two outs in the sixth inning, Jack Hamilton shut down the Braves the rest of the way, and the 6-3 victory was Denehy’s first major-league win.

After going 1-7 with the Mets, Denehy was demoted to Triple-A Jacksonville on June 28. With Jacksonville he was 3-3 in 11 appearances (10 starts) and had a 4.19 ERA in 58 innings. On August 7 he threw his last pitch of the season. It was a fifth-inning RBI single with two outs off the bat of Richmond’s Tommie Aaron that plated the third run in a 3-1 loss to the Braves’ farm club.22 Denehy was pitching in pain and “they took a series of 20 pictures and found a torn muscle in the rear of my arm near the armpit.” He rehabbed at home during the winter, doing much in the way of running, basketball, exercise, and swimming.23

In November 1967 it was announced that Denehy would be sent, along with $100,000, to the Washington Senators in exchange for manager Gil Hodges. While with the Senators, Denehy roomed with Mike Epstein. The pair was very much into self-help nutritional supplements and were very well-read, making their way through Ted Williams’s How to Be a Better Hitter and Psycho-Cybernetrics by Dr. Maxwell Maltz.24

The Senators wasted little time in checking to see if there was any residual damage in Denehy’s arm. In the first 1968 spring-training game, on March 7, he went up against the Yankees. In three innings, the only hit he allowed was a wind-blown single by Tom Tresh.25

But Denehy’s time with the Senators would be brief. Despite a good spring,26 he was not in the Senators’ starting rotation, and he was used sparingly. He appeared in three April games. Of the 13 batters he faced in two innings pitched, four got hits and four were walked. On April 29 Denehy was sent to Triple-A Buffalo, where, starting every fourth day,27 he went 9-10 with a 4.87 ERA in 25 appearances, all as a starter. His ninth loss of the season, to Syracuse on August 30, was perhaps his best start of the season. In the 2-0 defeat, he pitched the first eight innings and struck out 17 batters.

On February 1, 1969, the 24-year-old Denehy married 20-year-old Marilyn Waylock. They had two daughters, Kristin and Heather, before divorcing in 1987. He had met Marilyn, who was also from Middletown, after playing with the Mets in the Instructional League in 1965. Marilyn is the younger sister of John Waylock, Denehy’s teammate from the 1964 Middletown American Legion team. Daughter Kristin grew up to be a choreographer, and has had twin daughters.

After playing under new manager Ted Williams during spring training in 1969 and absorbing lessons from the master of hitting, learning “as much about pitching from Ted as I did from all of my pitching coaches combined,”28 Denehy began the season back at Buffalo and got off to a good start exemplified by pitching the first eight innings of a 3-0 shutout against Rochester on May 27. He was pitching in pain and receiving more and more cortisone shots, and by June 20 he was 2-4 with a 4.58 ERA. At that point Denehy moved on to Portland in the Pacific Coast League when he was traded by Washington to Cleveland for Lee Maye. With Portland he was 1-3 (4.37).

After the 1969 season, Denehy was assigned to the Indians’ Double-A club in Waterbury, Connecticut, and was drafted by the Mets Tidewater farm club on December 1. He went to spring training with his original organization, and he was assigned to Double-A Memphis at the start of the season. His arm was feeling better; he had found a new doctor and a new drug to ease the pain. Toward the end of Denehy’s time in Portland, Dr. Stanley Jacob administered dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and the results had him feeling better than he had since the injuries began in 1967.

(Jacobs has been referred to as the father of DMSO. In the mid-1970s, DMSO was approved for horses only.29)

After spending two months with Memphis, going 3-4 and striking out 49 batters in 46 innings, Denehy was promoted to Triple-A Tidewater. On August 4 he was the Denehy of old, striking out 13 batters in a 5-1 win over Louisville. He scattered seven hits and didn’t lose his shutout until the eighth inning.30 With Tidewater, he was 7-4 with a 3.29 ERA, and at the end of the season he was put on the Mets 40-man roster.

That winter Denehy was sent to Puerto Rico and played for Roberto Clemente with the San Juan Senadores.

Spring training went well for Denehy in 1971 and he thought he had a good chance to go north with the Mets, especially after his performance on March 13 when he pitched four no-hit innings against the Dodgers in relief.31 In what was to be his swan song for the Mets, he pitched one inning against the Yankees on March 28, allowing no runs and one hit. But as the exhibition season concluded, Denehy was traded to the Detroit Tigers along with veteran Dean Chance for pitcher Jerry Robertson and $75,000. He was assigned to Toledo, but after pitching in three games, he joined the Tigers and appeared for the first time on May 1. He relieved in 30 of his 31 appearances, and pitched batters high and tight. For the season, Denehy was 0-3 with a 4.22 ERA. He was credited with a save and three (retroactive) holds as the Tigers went 91-71 under Billy Martin, finishing second in the AL East.

“That fight brought our club together. It was one of the closest-knit clubs I had played with during my years in professional baseball.” — Bill Denehy about the 1971 Tigers.32

Denehy hit four batters during the season, and the second hit batsman proved memorable. In the opener of a doubleheader at Cleveland on June 18, the Indians’ Sam McDowell hit two Detroit batters, Willie Horton and Bill Freehan, as Detroit won, 4-3. Balls kept going in the direction of Detroit batters in the second game, and three Tigers (Freehan, Jim Northrup, Ed Brinkman) were hit in the first seven innings. Denehy entered the game in the bottom of the seventh inning with the Tigers trailing, 3-0. Cleveland scored another run that inning, and the score was 4-0 when Ray Fosse led off for Cleveland in the bottom of the eighth. Denehy hit Fosse in the ribs with a pitch.33 Whether or not this was intentional was of little concern to Fosse, who charged the mound. Denehy, with equal components of rage and smarts, defended himself. Per Watson Spoelstra, “Slender Bill Denehy … repelled Fosse with a kangaroo-style kick with his spikes and this way he could keep pitching and not be sitting in the trainer’s room with a sore hand.”34 As Sports Illustrated’s Ron Fimrite explained, “[T]he battle was joined, and the diamond was soon as warm with flailing ballplayers.”35 Denehy got the rest of the day off along with Horton and Ike Brown of the Tigers and Fosse and Gomer Hodge of the Indians.

Although hitting Fosse was not intentional, Denehy was not immune from throwing at batters at the behest of manager Billy Martin. On August 9, the Tigers were playing the Red Sox at Fenway Park. Denehy entered the game in the bottom of the sixth inning with the Tigers trailing, 10-7. The first batter up was Reggie Smith. Denehy drilled him and expected to be thrown out of the game. The umpires let him continue and he pitched two innings, allowing one run, before coming out for a pinch-hitter.

Otherwise, the season proved uneventful for Denehy. After the season he was assigned to the Toledo roster. He had faced his last major-league batter. He finished his 49-game major-league career with a 1-10 record and a 4.56 ERA.

Denehy spent the 1972 season wandering the minor leagues. He went to spring training with the Cardinals but was released before the season began. He signed in May with the Tucson Toros of the Pacific Coast league. His rage got the better of him on May 20, when he tagged Kurt Bevacqua in the mouth during a rundown play, precipitating a brawl reminiscent of what happened in Detroit the prior season.36 Denehy was released by Tucson on June 3 and hooked up with Kinston, the Yankees affiliate in the Class-A Carolina League. While there, in one of his two appearances, he pitched five no-hit innings with 5 walks and 5 strikeouts.

On June 19, for one day only, Denehy joined Triple-A Syracuse and pitched an inning of relief in an exhibition against the Yankees. In July he signed with the Double-A Reading Phillies in the Eastern League, with whom he spent the balance of the season.

The offseason in Connecticut was but a blur punctuated by equal parts of rage and addiction to drugs and alcohol. Denehy’s major-league career had fallen short of its initial promise and the stress of his deteriorating behavior was beginning to take a toll on his marriage. However, there was a glimmer of hope on the horizon.

In the spring of 1973 Denehy was back in Florida to give it another try with the Phillies. He was released but hooked on with the Double-A Bristol Red Sox. Bristol was not far from his Connecticut home and he got to spend the summer with Marilyn. On June 17 of that season, his family grew with the birth of his first child, Kristin. But on the field, it was not a good season. He went 1-5 with a 4.73 ERA before being released. In the spring of 1974, Denehy was briefly in the Giants’ spring camp and was released for the last time.

Life after baseball was a roller-coaster of opportunities wasted, addictions encountered, and mischievous behavior. Denehy’s first venture (he was still only 28 years old) was real estate in Arizona. Although he had some success, the principal result of his time in Arizona was a cocaine habit. Baseball, however, was not out of his system entirely and he pitched semipro ball in the Southern Arizona Association. While Bill and Marilyn were in Arizona, baby number two, Heather Lynn Denehy, entered the world on October 27, 1977.

A new career began for Denehy in 1981 when he joined the staff of the fledgling Enterprise Radio, based in Connecticut, and was on the air as a weekend radio talk-show host from 1:00 A.M. to 4:00 A.M. Soon, he became “Wild Bill” Denehy, cowboy hat and all. He covered spring training and college basketball and learned his craft working with producer John Chanin. However, his addictions to alcohol and drugs were still in play and there were nights when Denehy’s behavior was unacceptable, especially when he arrived home late to his distraught wife.

On June 12, 1981, major-league ballplayers had gone on strike and Denehy was not too sure of the status of the broadcast network. He contacted the Bristol Red Sox and while still with Enterprise, joined the Bristol Red Sox as pitching coach in August. Enterprise Radio ran into difficulties and shut down after the baseball season. Denehy remained with Bristol as the pitching coach. He stayed with the team through 1983, its first year in New Britain, and coached future Red Sox Oil Can Boyd, Al Nipper, and Roger Clemens. After the 1982 season, Denehy taught a course in baseball at Middlesex Community College in his hometown of Middletown. In Baseball 101, he discussed theories on the art of baseball.37 He and the New Britain Red Sox parted ways after the 1983 season.

“Buy a brick, build a stadium. Sprinkle some seed and then go out and hustle. I’m a salesman, but I’ve never had the opportunity to sell baseball. That would really be fun.” — Bill Denehy, August 16, 1984.38

Denehy was out of baseball as the 1984 season began, and although he found a job with a bank, he was miserable and ached to get back in the game. He was hired in August as the head baseball coach at the University of Hartford. The school had not won a game in two seasons, had lost 29 consecutive games, and its facilities were subpar. Home games were played off-campus.39 Denehy hired three assistants to help him for the 1985 spring season, friends Don “The Grog” Lombardo, don’s brother Ted, and Paul LaBella. Under the stewardship of university vice president Bob Chernak, the school was moving to Division I in basketball and baseball, even without a playing field for baseball. Denehy’s first players were willing, but not quite able, and the losses continued to pile up. It would be a bit of time before the most talked-about player on the team was someone other than a 5-foot-1-inch second baseman named Tom McVetty whom his mates called “Dirt.”40

There was a game that first year in which Denehy could not contain his rage. The opponent was Amherst. Amherst scored seven runs in the first inning and in the second inning a brawl broke out with Denehy not playing the peacemaker role. Amherst went on to win, 13-1, and the streak was up to 32. The streak grew to 3841 before the Hawks defeated Bridgeport on April 9. They won only two games that season, but Denehy was convinced he could turn the program around. One note of encouragement was that his top pitcher, John Tuozzo, had been drafted by the New York Mets. Although Tuozzo made it only as far as Class A and won only six minor-league games, Hartford was being noticed. Tuozzo was the second player from the University of Hartford to be drafted and the sixth to play professionally. Those numbers would increase substantially over the next several years, and two of Denehy’s recruits would be the first University of Hartford players to perform at the major-league level.

To build Hartford into a winner, it would take great recruiting, and Denehy set out to get the best recruits available. With a blend of blarney and craziness, he not only recruited but set about to raise funds for his ambitious goals. The recruiting began during the 1985 season, and by the time the 2-24 season was over, the Hawks had grabbed off several top players from Connecticut. One of them was catcher Rick Murray of Xavier High School in Middletown, but it would be another player from Xavier, recruited the following year, who would jump-start the Hartford program to prominence. The goals included an expanded schedule. On November 20, 1985, a dinner was held to raise funds for the baseball program. It was “The First Annual Baseball Dinner: An Evening with George Steinbrenner,” and “The Boss” came to West Hartford.42 The team, whose bus broke down en route to Yale for the opener in 1985, would be jetting to Arizona in March 1986. On board were 19 prized freshman recruits.43

The Arizona trip in 1986 produced losing results but a couple of the recruits left their mark. One was right fielder Brian Crowley, who homered on the first pitch he saw and gave the Hawks an early lead. Also homering in a 21-3 loss was Pat Hedge.44 The two would be the first of Denehy’s recruits drafted by major-league teams. Through their first 29 games, the Hawks had five wins, including a 15-4 drubbing of Central Connecticut, and were in the process of rewriting the school’s record books as team members scored more runs, hit more homers, and batted for higher averages than ever before.45

Hartford which joined the Eastern Collegiate Athletic Conference in 1986, got its first ECAC win (after eight losses) in the first game of a doubleheader against Vermont on April 26, but it was one of those “step forward, step back” days for Denehy and his Hawks. A bench-clearing brawl broke out in the second game and by the time the dust settled, Denehy was ejected and the game ruled a forfeit.46

Although the team put up another losing record (8-34), there was more help on the horizon. The list of recruits was headed by Jeff Bagwell of Xavier High School. Denehy’s assistants were familiar with Bagwell from American Legion play, and Denehy had already recruited two Xavier players.

Although the team put up another losing record (8-34), there was more help on the horizon. The list of recruits was headed by Jeff Bagwell of Xavier High School. Denehy’s assistants were familiar with Bagwell from American Legion play, and Denehy had already recruited two Xavier players.

The first time Denehy saw Bagwell was in Bagwell’s junior year at Xavier. The pro baseball scouts had not been impressed with Bagwell, but Denehy saw something. He remembered in 1994 that “I saw him as a junior for the first time and the thing that impressed me the most was that he had an awful lot of power to the opposite field.”47 Hartford assistant coach Paul LaBella headed the charge to entice Bagwell. The only issue was that Bagwell wanted to continue to play soccer, where he had been an All-State selection. By 1986, the years of a college athlete playing two sports were over, especially in baseball, for which many schools had both fall and spring programs. Denehy insisted that Bagwell commit to baseball alone, and Bagwell first played baseball for Hartford in the fall of 1986.

During the summer of 1986, Denehy got back into radio, hosting a show on WGAB Radio. A seemingly positive change for Denehy was made at Hartford in the autumn of 1986 when Don Cook was named athletic director. On January 31, 1987, Denehy put together a baseball clinic at which former major leaguers Tom House and Lou Piniella participated. However, Denehy would not be at Hartford long enough to see his most famous recruit emerge as a star. By then Denehy’s argumentative nature was established, and when he did not attend the annual baseball dinner in the fall of 1986, the establishment at the University of Hartford was disturbed.

With Bagwell and other new recruits, the Hawks took to the field in 1987, but they were still a young team and still prone to mistakes. On their Florida trip, they made 27 errors to the opponents’ 10, and their pitchers allowed a staggering 55 walks to the opposition’s 33.48 Through their first 10 games, they were 1-9. Then the squad, which included 18 freshmen and sophomores on the 22-man roster,49 began to jell. Although the team was only 6-14 in its first 20 games, it got off to a good start in the ECAC, taking two of three games from Maine. The team was improving, and Bagwell’s bat was as good as expected. His fielding at shortstop, however, was not helping the team and this was evident after just a few games. Denehy moved Bagwell to third base. It would prove to be Denehy’s last role in the development of Bagwell.

Denehy’s dream of a stadium for Hartford would happen, but by the time it did, in 2017, his eyesight had diminished to the point that he would not see it. Indeed, he would leave the University of Hartford scene before many of his recruits completed their education at the school.

Denehy’s run-ins with authorities, on the field or at the university, would continue and be his undoing. On April 14, 1987, the Hawks played the UConn Huskies and the mood was tempestuous. Brawls erupted in both the fifth and sixth innings and Hartford players Pat Hedge and Tony Franco were in the middle of things. The game was stopped by umpire Barry Chasen, and UConn, leading, 2-1, at the time, was declared the winner.50 In the aftermath of this game, Denehy was reported to have made comments detrimental to personnel at UConn. Speaking with writer George Smith of the Hartford Courant, athletic director Don Cook said, “The alleged comments made by our coaching staff … do not convey a message which is representative of the athletic department or the university and for that reason we apologize. I [personally] [disassociate] myself from such statements as does the university because they certainly don’t reflect the general philosophy of the university.”51

On April 16, Denehy and his coaches were fired. The most damning of the statements attributed to Denehy in an article printed in the Norwich Bulletin indicated that he had particularly harsh views toward UConn assistant coach Mitch Pietras and indicated that the next time Pietras (who was also a soccer referee) went to the Hartford campus, he hoped “somebody bombs his car.”52

Cook, once considered a blessing by Denehy when he arrived, now was the person who fired Denehy. He took over as coach of the 7-15 squad, and the firing hit the players hard. Rick Murray was particularly distraught, calling the firing “a major setback,” and adding, “We were just learning how to win. There was a different feeling coming back on the bus from Maine Sunday after winning two of three games. Now this. Now what?”53

The Hartford program would continue its upward climb. Despite the turbulence as the team stumbled to an 11-27 record in 1987, Jeff Bagwell went on to complete his freshman season with a .402 batting average with university records in homers (7), RBIs (32), hits (51), total bases (86), and doubles (12).54 The next season, with Denehy recruits Hedge and Crowley serving as co-captains and Bagwell continuing his hitting surge, the team advanced to postseason play in the ECAC Tournament.

Of the players recruited by Denehy, four played professionally. Pitcher Mark Czarkowski was undrafted but signed with Seattle and played seven seasons of professional ball. Three players were drafted. Pat Hedge and Brian Crowley fell short of making it to the majors, but Jeff Bagwell went on to a Hall of Fame career. Denehy’s impact on the Hartford program was not lost on his successor, Dan Gooley, who said, “I give Bill a lot of credit. He’s a friend and we are all coaching brothers. He did a great job here. I feel for him.”55

Denehy, however, would have issues over the coming years. His marriage was coming apart at the time of the firing and he and Marilyn were divorced in November 1987. His ongoing drug use escalated, and his rage did not dissipate. He worked in construction for a while, played some semipro baseball, and in 1988, through an attorney, he wrote to the University of Hartford to try to reach a “settlement” that would have the university share in the responsibility for the events of April 1987 and not have the “dark cloud hang solely over Bill’s head on the issue.”56

Over the next couple of years, Bill found his way in and out of jobs in radio in Connecticut, and he relocated to Florida. He had hoped to play in the Senior Professional Baseball Association in the fall of 1989, but injuries sustained in a car accident kept him off the field. He returned to broadcasting and again, starting in November 1990, became a talk-show host, this time at WFNS in Tampa.57 Differences with management over the firing of a production assistant led to his dismissal from that position in March 1991.58 He also became more abusive of drugs during his time in Florida, and although he found some work broadcasting games on television with the Sunshine Network, his life was without any meaningful direction.

On June 15, 1992, Bill Denehy’s life reached a turning point. He had been in Connecticut visiting his daughters, who were participating in the Connecticut Interscholastic Athletic Conference softball tournament. Heather was a sophomore star pitcher at Mercy High School in Middletown and pitched a one-hitter on May 29.59 Her coach was Paul LaBella, who had been Bill’s assistant during his time at the University of Hartford.60 Her team was eliminated on June 8,61 but Bill stayed on through Father’s Day. Bill still had a drug habit. He was about to depart for Florida. At breakfast, in a moment of introspection, he asked his daughters, “Is there something we didn’t do this time that you’d like to do the next time we’re together?” His younger daughter, Heather, said, “I’d like to play catch.” As Denehy remembered in his book Rage, “[H]er words hit me like a ton of bricks that weighed heavily on my heart. I was an ex-major leaguer [who should have been playing catch with his daughters all along], yet I was so screwed up [from the alcohol and drug abuse] … that I couldn’t spend fifteen minutes playing catch with my daughter.” At that point, he committed to turning his life around.62

He returned to Florida and sought to rehabilitate his life. A month after his talk with Heather, he enrolled as an outpatient at Glenbeigh Hospital in Orlando, where he was counseled by Dr. Irving Kolin and executive director John Brandenburg. It was to them that he first came clean about his problems and they set him on the path to recovery. In group and individual therapy sessions led by Vicky O’Grady, he came to grips with his disease, the roots of his disease, and the need to address the issue of rage that had imprisoned him since his days in Little League.63

Denehy stayed in broadcasting and hosted a program called Comeback, which focused on people, mostly sports figures, who had overcome various addictions and afflictions.64 He went on to form, with Ryne Duren, the National Association of Recovering Professional Athletes (NARPA), whose purpose is “to educate the young about the dangers of drugs and alcohol and provide support for pro athletes who have had and may still have addictions.”65

As it turned out, the goals of NARPA and Glenbeigh could not be fully realized. Both organizations failed to survive, with Glenbeigh going bankrupt in March 1995 and NARPA folding its tent in 1994. But Bill Denehy did survive, found other work, and was sober.

He was inducted into the Middletown Sports Hall of Fame in 1995. For a time, he worked with Edwin Watts Golf in Florida but was fired in 1998 over various incidents at work, some related to his ongoing rage issues. Despite his sobriety, he still had issues with rage. But he found his calling, taking to the lecture circuit to warn people about the dangers of alcohol and drug abuse.

Denehy’s father had died on April 11, 1996, after relocating to Florida in 1995. In 2000, his mother, who was living with him in Florida, was stricken with Alzheimer’s and died on March 1, 2004, at the age of 89.

Over the next years, Denehy was in and out of jobs, including a position at Universal Studios in 2003. That year, he co-authored a book, Intrinsic Golf: It’s Within You.66 But all the rage and all the cortisone and all the drugs took their toll.

Denehy’s life entered a new phase on January 19, 2005. He woke up that day unable to see out of his right eye.67 His retina was damaged and, even with surgery, he lost sight in the eye. Ultimately, there would be problems in his left eye as well, leaving him virtually blind. He maintained that the many cortisone injections he received during his days in the majors were a major contributor to his vision difficulties.

In December 2013 Denehy was able to partner with Kane, a Guide Dog provided by Fidelco, a group headquartered in Bloomfield, Connecticut, not far from Denehy’s boyhood home. In August 2014, Denehy and Kane returned to Middletown for the 50th reunion of the Woodrow Wilson High School Class of 1964.68

In recent years, Denehy has reconnected with Marilyn, Kristin, and Heather. He wrote his memoirs in Rage: The Legend of “Baseball Bill” Denehy, and he still follows University of Hartford baseball — and yes, before his eyes failed him, he did have that catch, on Thanksgiving Day in 1992, with Heather!69

Last revised: May 14, 2019

This biography was originally published in “Jeff Bagwell in Connecticut: A Consistent Lad in the Land of Steady Habits” (SABR, 2019), edited by Karl Cicitto, Bill Nowlin, and Len Levin.

Sources

In addition to the sources shown in the notes, the author used Baseball-Reference.com, Ancestry.com, and the following:

Canfield, Owen. “From Middletown to the Majors Through Hell and Back,” Hartford Courant, March 7, 1993: A1, A12.

Karmel, Terese. “‘Wild Bill’ Denehy Finds Plate in Job as Brisox Pitching Coach,” Hartford Courant, May 15, 1982: C3.

Lang, Jack. “Potent Potion for Bum Arm — Denehy Ready Now,” The Sporting News, March 13, 1971: 44.

Post, Fred. “Black Beauty Set Pitcher Off in Wrong Direction,” Hartford Courant, March 31, 1999: 8.

Schmitz, Brian, “Former Pitcher Denehy Was in Howe’s Shoes,” Orlando Sentinel, December 12, 1992: B1.

Sears Campbell, Diane. “An Inspired Speaker Gets Some Motivation,” Orlando Sentinel, June 13, 1999: H-4.

Trecker, James. “Legion Baseball,” Hartford Courant, July 12, 1964: 8C.

Notes

1 George Smith, “Hartford Fires Denehy for Post-Fight Comments,” Hartford Courant, April 17, 1987: E 10.

2 Smith, “They’re Hawking Hartford’s Hitter,” Hartford Courant, June 4, 1989: E4.

3 “Francis Denehy Obituary”, Orlando Sentinel, April 12, 1996: 46.

4 “Moose Little Leaguers Win District Nine Title,” Hartford Courant, August 3, 1958: 5D.

5 “Upset Wins Enliven Legion Races: Denehy Hurls No-Hit Gem in Zone 4,” Hartford Courant, July 11, 1963: 14.

6 “Middletown Tops Wilson by 48 to 38 Before 2,500 Fans,” Hartford Courant, February 29, 1964: B-14.

7Hartford Courant, 1964 (Games in which Denehy struck out 10 or more batters were 4/17, 4/29, 5/05, 5/15, 5/30, 6/10, and 6/15.

8 “Woodrow Wilson Nips Middletown,” Hartford Courant, May 31, 1964: C-4; “Youth Hurt in Wrecker Accident,” Hartford Courant, February 25, 1963: 18.

9 “Denehy’s Gem Wins for Wilson,” Hartford Courant, June 11, 1964: 18.

10 Bill Newell, “Bill Denehy Hurls Wilson to Class-B Title with 8-1 Win,” Hartford Courant, June 16, 1964: 22.

11 James Trecker, “Bristol Defeats Middletown to Gain Final,” Hartford Courant, August 9, 1964:2C.

12 Trecker, “Legion Baseball,” Hartford Courant, July 12, 1964: 8C.

13 “Mets Think Bill Denehy is Top Pitching Prospect,” Hartford Courant, August 11, 1965: 22.

14Bill Denehy (with Peter Golenbock), Rage: The Legend of “Baseball Bill” Denehy (Las Vegas: Central Recovery Press, 2014), 52-53.

15 Joe Donnelly, “Westrum May Make a Point with Denehy,” Newsday, April 4, 1967: 21A.

16 Red Foley, “Jax Strings Along Mets, 2-0, Richie Ruins Denehy’s Debut,” New York Daily News, April 17, 1967: 54.

17Joe Donnelly, “Denehy Reminds People of Rohr: Allen Spoils Met Rookie’s Debut,” Newsday, April 17, 1967: 21A.

18 Steve Jacobson, “Right Up Allen’s Alley,” Newsday, April 24, 1967: 32A.

19 Emily Badger, “Pitcher’s ‘World Fell Apart’ the Day He Injured His Arm,” Orlando Sentinel, April 10, 2005: C-13.

20 Joseph Durso, “Denehy is Picked to Face Marichal,” New York Times, May 4, 1967: 46.

21 Fred Post, “Black Beauty Sent Pitcher Off in Wrong Direction,” Hartford Courant, March 31, 1999: Middletown Section: 8.

22 Shelley Rolfe, “R-Braves Defeat Suns, 3-1,” Richmond Times Dispatch, August 8, 1967: B6.

23 George Minot Jr., “Nats Denehy Faces Yanks Today: Newcomer Eager to Face Challenge,” Washington Post, March 7, 1968.

24Washington Post, March 1, 1968: D1.

25 Merrell Whittlesey, “It was a Great Day for Pitchers,” Washington Evening Star, March 8, 1968: A17.

26 Morris Siegel, “Senators Eye Fourth,” Washington Evening Star, April 6, 1968: 14.

27 Whittlesey, “Humphreys Recalled, Denehy Farmed Out,” Washington Evening Star, April 29, 1968: 18.

28 Denehy and Golenbock, 104.

30 Ron Coons, “Denehy Whiffs 13, Tides Win,” Courier Journal (Louisville, Kentucky), August 5, 1970, B-7.

31 Bill Lee, “Bill Denehy Challenges for Mets Bullpen Job,” Hartford Courant, March 14, 1971: C-1.

32 Denehy with Golenbock, 132.

33 Vito Stellino (Associated Press), “Angels Boil — Cleveland Explodes,” Jersey Journal, June 19, 1971: 15.

34 Watson Spoelstra,” Great in the Clutch, Gates Wants a Regular Job,” The Sporting News, July 10, 1971: 11.

35 Ron Fimrite, “Billy the Kid as Peacemaker,” Sports Illustrated, June 28, 1971: 18.

36 Russell Schneider, “Aspro: Tribe Has mark of Winner,” Cleveland Plain Dealer, May 23, 1972: 3-C.

37 Terese Karmel, “Middlesex Offers Baseball 101,” Hartford Courant, August 28, 1982: C4.

38 Owen Canfield, “Hartford Needs a Stage to Showcase Baseball,” Hartford Courant, August 17, 1984.

39 Canfield, “Crazy Like a Hawk: Sky’s the Limit at U of H,” Hartford Courant, July 17, 1985: C1.

40 Smith, “Hawks Struggling to Halt Draught,” Hartford Courant, April 2, 1985: C1.

41 Smith, “Rocky Hawks Sitting on 2 Milestones,” Hartford Courant, April 20, 1985: C5.

42 Tom Yantz, “U of H Gets Steinbrenner for Dinner,” Hartford Courant, October 11, 1985: C2

43 Smith, “Frosh-Filled Hawks Leaping Into Big Time Baseball,” Hartford Courant, March 2, 1986: E19.

44 Jack Magruder, “UA Uses Hartford for Batting Practice,” Arizona Daily Star(Tucson), March 12, 1986: C2.

45 Smith, “Hawks End Nine-Game Skid,” Hartford Courant, April 16, 1986: D7.

46 Don Fillion, “Forfeit Gives Vermont Split,” Burlington (Vermont) Free Press, April 27, 1986: 3C

47 Smith, “He’ll Always Be Player from the Old School,” Hartford Courant, October 28,1994: C1.

48 Smith, “Yale Sweeps Slumping Hartford,” Hartford Courant, March 29, 1987: 33

49 Smith, Hawks Go Bear Hunting, Get a Pair,” Hartford Courant, April 14, 1987: D2.

50 Smith, “Brawls Halt UConn-UH Game,” Hartford Courant, April 15, 1987: D1.

51 Smith, “UConn and U of H Say No Rematch,” Hartford Courant, April 16, 1987: D2.

52 Smith, “Hawks’ Ax Falls,” School Fires Baseball Coach, Staff,” Hartford Courant, April 17, 1987: E1.

53 Smith, “Hartford Fires Denehy for Post-Fight Comments,” Hartford Courant, April 17, 1987: E 10.

54 Smith, “Hawks Turn a Page in Baseball program, Hartford Courant, August 27, 1987: D3.

55 Canfield, “Give Gooley a Letter ‘S’ for Success,” Hartford Courant, April 28, 1988: G-1, G-6.

56 Tom Yantz, “The Sporting Look.,” Hartford Courant, June 9, 1988: D2.

57 “WTKN Evens the Score,” St. Petersburg Times, November 16, 1990: 17.

58 Steve Persall and Roger Fischer, “Q-105 May Be on the Rebound,” St. Petersburg Times, March 29, 1991: 19.

59 “Mercy’s Denehy Pitches One-Hit Shutout,” Hartford Courant, May 30, 1992: E4.

60 Chris Sheridan, “Pitcher Near Top as School Year Winds Up,” Hartford Courant, June 7, 1992: H4.

61 “Holy Cross Turns Back Mercy, 8-1,” Hartford Courant, June 9, 1992: D5.

62 Denehy with Golenbock, 255-256.

63 Canfield, “From Middletown to the Majors Through Hell and Back,” Hartford Courant, March 7, 1993: A1, A12.

64Catherine Hinman, “Radio Waves,” Orlando Sentinel, November 7, 1992: E2.

65 Canfield, “November Is Season to Hunt Autographs,” Hartford Courant, November 12, 1993: E3.

66 Bill Denehy with Bob Gold, Intrinsic Golf: It’s Within You: How to Play Better Golf When You Don’t Have Time to Practice or Take Lessons(Bloomington, Indiana: Trafford Publishing, 2003).

67 Badger, “Before There Were Steroids: Former Players Say Cortisone Abuse Once Was Rampant in Big Leagues,” Orlando Sentinel, April 10, 2005: C12.

68 Steven Goode, “Former Major Leaguer Bill Denehy Says He’s Thankful for Fidelco Guide Dog,” Hartford Courant, August 22, 2014.

69 Brian Schmitz, “Former Pitcher Denehy was in Howe’s Shoes,” Orlando Sentinel, December 12, 1992: B1.

Full Name

William Francis Denehy

Born

March 31, 1946 at Middletown, CT (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.