George Suggs

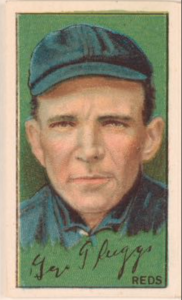

“A ballplayer making good in the big league, a handsome fellow in any company, his waving brown hair carelessly thrown back from his brow, his voice pitched in those taking North Carolina accents, was it any wonder that he found ready listeners?”1 Thus wrote the Twin-City Daily Sentinel (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) of George Suggs, whose reputed fixation on the opposite sex nearly cost him his burgeoning baseball career. The “wee” hurler was able to shift his focus to the game, however, and later became a 20-game winner in both the National and Federal Leagues.2

“A ballplayer making good in the big league, a handsome fellow in any company, his waving brown hair carelessly thrown back from his brow, his voice pitched in those taking North Carolina accents, was it any wonder that he found ready listeners?”1 Thus wrote the Twin-City Daily Sentinel (Winston-Salem, North Carolina) of George Suggs, whose reputed fixation on the opposite sex nearly cost him his burgeoning baseball career. The “wee” hurler was able to shift his focus to the game, however, and later became a 20-game winner in both the National and Federal Leagues.2

George Franklin Suggs was born in Kinston, North Carolina, of English and Scottish descent on July 7, 1882, to John and Winifred Suggs. Siblings Edward, Willie, Ada (who died at age 3), and Lula rounded out the family. John was a farmer and Winifred was a homemaker. Shortly after the death of his father in 1899, Suggs left home to attend prep school near Greensboro, North Carolina, at Oak Ridge Institute. There he honed the mound skills he had begun developing at home while playing for amateur teams in Kinston and nearby Greenville. A Kinston paper called him a “brilliant” pitcher, and a nearby professional club took notice.3

In 1902 Suggs made the jump to professional ball, joining the Greensboro Farmers of the Class-C North Carolina League, where he quickly made a positive impression. “George Suggs, the Kinston boy, is eligible to the mayoralty of Greensboro now,” proclaimed the Kinston Daily Free Press after the right-handed hurler tossed a shutout against Raleigh in May.4The following year, Suggs headed north to begin the season playing for Nashua (New Hampshire) of the Class-B New England League.5 Around midseason, he returned south to pitch for the independent Columbia (South Carolina) club, where he continued to show promise, throwing a no-hitter against Augusta in August.6

The 1904 campaign found Suggs back in professional ball, this time in the Class-C South Atlantic League with the Jacksonville Jays, with whom he spent most of the season. He finished with a pedestrian 12-13 record, at one point even finding himself suspended for a week because of “sulkiness” after a poor mound performance.7 Still, the 5-foot-7, 168-pound pitcher showed enough promise to finish the season in Class-A, with the Atlanta Crackers of the Southern Association.8 Released by Atlanta before the 1905 season, he landed with league rival Memphis.

Suggs found a home in Memphis, spending the 1905-1907 seasons pitching for the Egyptians —and pitching well. Despite being known as a hard-luck pitcher, Suggs averaged 16 wins during his three seasons with Memphis and was recognized as one of the league’s best hurlers.9 His time in Memphis was highlighted during a doubleheader against Nashville in September 1906, when he tossed two complete-game shutouts on the same day, one of them an 11-inning no-hitter.10Earlier that year, a promotion to begin the season in the big leagues nearly came to fruition for Suggs when the National League’s Brooklyn Superbas secured his services before ultimately releasing him back to the Egyptians before the season.11 He did not have to wait much longer for his break, however. Upon recommendation of respected Southern Association talent evaluator (and Atlanta manager) Bill Smith, the Detroit Tigers purchased Suggs’s contract during the summer of 1907.12 In a strange turn of events shortly after this news broke, a Memphis socialite and “beautiful young woman,” Pearl Mendall, unsuccessfully attempted suicide by morphine overdose when prevented from seeing Suggs, with whom she was admittedly “infatuated for three years.”13 This incident marked the beginning of controversial issues surrounding women that plagued the pitcher with the “princely gait and engaging smile” in the future.14

Suggs’s time in Detroit got off to a rocky start when he found himself in a contract battle with club President Frank Navinbefore the 1908 season. After “considerable dickering over salary,” Suggs ended his contentious holdout and reportedly signed for either $2,200 or $2,400 per year.15 Things went from bad to worse when after taking the loss in a shaky big-league debut against the St. Louis Browns, the diminutive righty found himself suspended by the Tigers for “not being in playing condition.”16 This nearly led to Suggs being sent down to the St. Paul Saints of the Class-A American Association; however, the club decided to retain his services when another of Detroit’s young arms, Herm Malloy, was unable to play at the time.17 Although he remained with the Tigers for the rest of the season — and bounced back from his suspension with a complete-game victory in his second big-league appearance — he finished his rookie campaign appearing in only six games for the World Series runners-up.

Despite entering the following spring in much better physical condition, Suggs again saw limited playing time as the 1909 season progressed.18 The Brooklyn Daily Eagle in July sarcastically reported this of the little-used pitcher: “Premier fungo batting honors should go to George Suggs of the Tigers. He has been a Detroiter for two years, and has pitched few games, devoting the remainder of his time to knocking out flies to the Tiger outfield.”19 Although he had been unsuccessful to that point on the diamond, Suggs was very successful romantically with women, rarely being seen with the same one twice. His teammates reportedly said that “of all the lady-tamers who ever allowed their eyes to goo-goo into a crowded grandstand, George Suggs holds the championship.”20 Detroit manager Hughie Jennings cautioned Suggs to prioritize baseball; however, the “feminine adulation was meat and drink to the twirler and he refused to heed the advice.”21 Jennings and Navin sent Suggs back down to the Southern Association in mid-July, with one newspaper suggesting that the 27-year-old had “flirted himself back to the minors.”22 In the three-pitcher deal, the Mobile Sea Gulls received Suggs, Frank Allen, and $2,800 in exchange for Bill Lelivelt. All told, Suggs posted a 2-4 record in only 15 mound appearances (five as a starter) in his two seasons with Detroit. He had a differing opinion of the reason for his demotion, believing it to be due to a lingering injury along with the logjam of quality pitchers on Detroit’s staff.23 “I was a green youngster and Jennings had three or four experienced men on whom he could rely perfectly,” Suggs contended. “It was very natural that he would not take any chances on me when Bill] Donovan, George] Mullin and the others were going along well. If he hadn’t been fighting for every game in order to cinch the pennant I would have had more opportunities, and I am sure that I could have stayed there.”24

Despite finishing the 1909 campaign in Mobile with a lackluster record, Suggs nonetheless was once again recommended to a major-league team by former Atlanta manager Smith — this time to the Cincinnati Reds. In November, Smith persuaded Cincinnati manager Clark Griffith and scout Louis Heilbroner to obtain the foundering hurler.25 In justification of the acquisition, Griffith reportedly said that “it is not always the man with the best paper record who proves to be the best man in the box.”26 The Cincinnati media seemed to concur, with one local sportswriter deeming Suggs to be the “best pitcher in the Southern League.”27 And former league opponent Otto “Dutch” Jordan of Atlanta also heaped praise upon the newest Red. “Suggs is 100 percent too strong for the Southern League,” said the Crackers’ team captain. “He can make his mark anywhere. He is a wonder and if worked often enough will win a big majority of his games in any company.”28 Jordan’s comments proved to be quite prescient.

Described as “not a very big fellow” but “wiry” with a “powerful pair of shoulders,” Suggs looked “exceptionally good” heading into the Reds’ 1910 campaign.29 And his demeanor seemed to change compared with what he had exhibited during his stint with Detroit. “Mr. Suggs, though a gentleman in every sense of the word, is ruthless when he faces the opposition in a business way, and allows no consideration to interfere with his method of attack,” sportswriter Jack Ryder wrote after a dominating preseason performance by Cincinnati’s new pitcher.30 Suggs parlayed this promising beginning into three fine seasons for the Reds, in which he became the club’s best and “most dependable twirler.”31From 1910 to 1912, Suggs featured an ERA nearly a half-run better than league average, regularly appeared among the top 10 league leaders in numerous pitching categories, and posted winning records each year on losing Cincinnati teams. He tallied 54 victories, including a 20-win season in 1910; only two other NL hurlers had more victories during that three-year stretch.

Suggs’s success was undoubtedly due in large part to the excellent control he possessed, as evidenced by his low walk rates. It was also attributed, however, to the translation of his academic knowledge of mathematics into an analytical pitch-to-contact approach on the mound. “It is, therefore, easy for him, without the aid of pencil and paper, but simply by a mental calculation, to figure out that even the best batter has only one chance in three of hitting the ball safely if he is forced to bing away at it,” wrote the Cincinnati Enquirer of Suggs’s thought process. “With the average hitter it is only one chance in four. Applying this knowledge to his work as a pitcher Mr. Suggs dopes it out that while one man is getting a hit he will be getting three, or at least two, on chances that his fielders can handle.”32 The pitcher with the “wicked glint in his optics” also became the “most feared twirler” in the league due in part to a less cerebral method — his propensity for throwing beanballs.33 “This fellow Suggs is the swellest beanball expert in the land,” said an unnamed teammate.34 In 1911 one of his beanballs struck the Chicago Cubs’ Frank Chance. Although Chance’s tendency to crowd the plate made him a frequent target for beanings, Suggs’s beanball was reportedly one of the most severe ever inflicted on him. Chance had significant health concerns and played little after this incident; thus, it is believed by many that it was Suggs who veritably cut the future Hall of Famer’s career short.35

After his fine first three campaigns with the Reds, Suggs “could not get to going just right” in 1913 despite again being a mainstay of the pitching staff.36 His struggles on the mound that season reached a head on August 11, when he allowed a record eight consecutive hits in one inning during a 13-1 drubbing by the Pittsburgh Pirates.37 With Cincinnati at the time languishing around the bottom of the standings, the club sought to overhaul its roster with some younger talent. And with manager Joe Tinker reportedly dissatisfied with the performance of his inconsistent 31-year-old hurler, Suggs became a roster casualty after being placed on waivers.38 He finished the year in Cincinnati with a disappointing 8-15 record and a 4.03 ERA. In October the St. Louis Cardinals, the Reds’ cellar-dwelling league rival, acquired Suggs’s contract in a cash deal worth a reported $1,500.39 Cardinals manager Miller Huggins planned to use him as a “finisher”; however, Suggs ultimately never toed the slab for the club due to a curious turn of events that soon began to unfold.40

Earlier in 1913, the newly formed Federal League arose as a six-team independent league from the debris of the defunct United States League, which had begun play a year prior. Despite the fact that it located most of its teams in or near big-league cities and “intended to become the third major league,” the Federal League respected the contracts of Organized Baseball, and as such fielded rosters stocked full of minor-league talent.41 After its disappointing inaugural season, during which it attracted little national attention, the league nonetheless found revitalized leadership and financial backing — and in the process turned the entire baseball world upside down. In addition to expanding to eight teams in preparation for its 1914 campaign, the upstart league boldly decided to directly take on the two major leagues. “It will be war to the hilt with Organized Baseball from this time forth,” proclaimed league executive Edward Krause.42 In deviating from its original plan of nonconfrontation, the Federal League began to successfully lure a significant amount of talent away from the National and American Leagues. “We learned last season that we must have a higher class of players and have concluded that the only thing to do is to get men who have reputations as big-league ballplayers,” Krause said.43 One of these ballplayers was Suggs, who had been in the midst of a salary dispute with St. Louis and “couldn’t resist the tempting offers of the outlaws.”44

Spurning the Cardinals to sign with the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins in February 1914, Suggs progressed through spring training in “fine shape” at the team’s camp in Southern Pines, North Carolina.45 “He is a curve-ball twirler, and the break on his offerings is quick and deceptive,” reported the Baltimore Sun of the veteran hurler. “And, too, Suggs knows how to pitch. He uses his brain and places the ball just where he decides the batter would rather not have it.”46 Unlike many of his contemporaries, Suggs did not throw a spitball. And although he certainly possessed sufficient knowledge of the burgeoning emery ball to teach it to others, it is uncertain whether he incorporated the taboo pitch within his game-day arsenal.47 Emery ball or not, Suggs bounced back from his disappointing swan song in Cincinnati to become one of the “kingpin twirlers of the Federal League” in 1914.48 At season’s end, the workhorse featured a strong 2.90 ERA in well over 300 innings pitched, and his 24 wins were good for fifth place in the league. Suggs’s strong pitching was a key enabler of the Terrapins’ finishing the tight pennant race in a competitive third place; however, the following year’s campaign saw both him and the club struggle.

With Baltimore stumbling to a distant last-place finish in the 1915 season, Suggs’s performance mirrored that of his team’s. Although he led the team with 11 victories, he lost 17 while seeing his ERA balloon well over a run higher than the prior year. Still, amid the disappointment there were some notable moments for the 33-year-old. Heading into September, it was speculated that Suggs led all three major leagues — and “may possibly have established a world’s record” — in picking off perhaps as many as 30 baserunners during the season.49 “Certainly no hurler in the country holds runners closer to the bases, and every player and manager in the Federal League will testify for Suggs in that respect,” wrote sportswriter C. Starr Matthews of the clever right-hander.50 Indeed, an unconfirmed report suggested that Suggs once caught a record seven runners napping at first base in a single game during his time in Cincinnati — especially impressive for a right-hander.51 And in addition to earning renown for snaring careless runners at first base, Suggs made headlines for throwing to that same bag for a completely different reason during game two of a Labor Day doubleheader in Buffalo. With two runners aboard in the bottom of the ninth inning of a tied game, the hurler found himself facing the Blues’ most dangerous hitter, Hal Chase, who earlier connected on an errant intentional ball and hit a walk-off home run to win game one. Having an open base available, Baltimore player-manager Otto Knabe again instructed his pitcher to intentionally walk Chase. Instead of tossing four intentional balls to his catcher, however, Suggs — “mindful of the fate that befell his teammate in the morning” — took no chances and curiously threw four intentional balls to first baseman Joe Agler.52 The umpire ruled Suggs’s “pitches” to be legal, and Chase “resigned himself to his fate and went to first” to load the bases.53 The strategy was ultimately unsuccessful, however, as Suggs unintentionally walked the next Buffalo batter to allow the game-winning run. Nevertheless, Suggs can take credit for employing the first-ever reported instance of this novel (and subsequently rare) intentional-pass tactic in the big leagues.54

After the 1915 season, an antitrust suit that the Federal League had previously filed against Organized Baseball was settled and peace between the warring leagues was restored. As a result, the outlaw circuit was disbanded, leaving Suggs without a big-league team for the 1916 campaign. Now unwanted by the St. Louis club from which he jumped to the Federal League two years earlier, the aging veteran had to settle for signing with the Richmond Climbers of the Double-A International League.55 Released by Richmond before appearing in a game, Suggs returned to his home state to join the Raleigh Capitals of the Class-D North Carolina State League after reportedly turning down offers to play for higher-level clubs.56 He spent about a month with Raleigh before announcing his intention to retire from baseball. In his final professional game, Suggs allowed only one earned run in a complete game against the Winston-Salem Twins. And while he also recorded a reported league-record 10 assists in the contest, the pitcher with the nickname Hard-Luck perhaps fittingly was tagged with the tough loss because of “his teammates’ erratic playing and inability to hit.”57 Despite the hard-luck ending to his career, Suggs “was given ovation after ovation as he passed the grandstand, the applause evidencing the popularity of the Kinston pitcher.”58 Upon leaving the game, Suggs posted a 99-91 record with a 3.11 ERA in 245 games (185 starts) during his eight big-league seasons.

Back in 1910, Suggs’s baseball earnings had enabled him to purchase a farm and house in Kinston for his mother. “Someday, I’m going back to live on that little farm, and when I do it will be the happiest day of my life,” he said at the time.59 Upon his retirement from baseball, Suggs made good on his promise and returned to his hometown to re-establish his roots along with his wife, Mozelle, a homemaker and Kinston socialite whom he married in 1914. The couple never had children. Over the years, Suggs purchased an interest in a bicycle company, operated a sporting-goods store, and later worked for two decades at a tobacco company.60 Outside of work, Kinston’s native son stayed active as a member of many organizations, including the local gun and literary clubs, the Elks Lodge, the Kiwanis Club, and the First Baptist Church. He counted fishing and hunting among his leisure-time hobbies.61

Suggs also remained close to the game. Not long after coming home to Kinston, he began grass-roots efforts to bring professional baseball to the area. Starting from nothing and within a span of only a few years, Suggs was instrumental in establishing an amateur Kinston team, organizing the independent Eastern Carolina League in which it played, and even designing the town’s stadium, West End Park.62 In 1925 the Kinston Eagles joined the Class-B Virginia League, bringing professional ball back to the city for the first time since 1908. Although Suggs was no longer directly involved with the club by that time, his contributions to reinvigorating baseball in Kinston are nonetheless still recognized as being pivotal to its fielding minor-league teams more or less regularly through 2019.63

In December 1948 Suggs suffered a cerebral hemorrhage, causing his health to suffer. On April 4, 1949, he died of pneumonia at the age of 66. He was buried in Maplewood Cemetery in Kinston.64 Unsurprisingly, in 1983 Suggs was posthumously inducted as one of the first members of the Kinston Professional Baseball Hall of Fame.65

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author accessed Suggs’s file from the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York; Ancestry.com; Baseball-Reference.com; Chronicling America; GenealogyBank.com; NewspaperArchive.com; Newspapers.com; and Retrosheet.org.

Notes

1 “Suggs Flirted Himself Back to the Minors,” Twin-City Daily Sentinel (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), July 21, 1909: 6.

2 Jim Nasium, “Gigantic Moore Beats Wee Suggs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 21, 1910: 10.

3 “Doings of a Day in Busy Kinston,” Daily Free Press (Kinston, North Carolina), March 21, 1902: 4.

4 “Kinston Kinetoscope,” Daily Free Press, May 20, 1902: 4.

5 “The Daily Free Press,” Daily Free Press, May 2, 1903: 4.

6 “The Daily Free Press,” Daily Free Press, August 10, 1903: 4.

7 “Jack Uses Discipline,” Tampa Tribune, July 21, 1904: 8.

8 “Atlanta Takes Third Straight,” Atlanta Constitution, August 14, 1904: 2.

9 “Gossip of the Spolts (sic),” Altoona (Pennsylvania) Tribune, September 21, 1907: 2.

10 “Two Goose Eggs, Nashville’s Part,” Nashville American, September 9, 1906: 7.

11 “The Stars,” Montgomery (Alabama) Times, March 6, 1906: 2.

12 “Climbers Should Lead Second Division Clubs,” Montgomery (Alabama) Times, August 6, 1907: 6.

13 “Suggs’s Girl Would Die,” Detroit Free Press, August 31, 1907: 10.

14 “Travelers Took the Last Game,” Arkansas Democrat, (Little Rock), April 15, 1907: 2.

15 “Wake Forest Elects Football Manager,” Charlotte (North Carolina) News, February 29, 1908: 6.

16 “Tigers Suspend a Young Twirler,” Pittsburg Press, May 18, 1908: 12.

17 “Suggs Case Hangs Fire,” Pittsburg Press, May 25, 1908: 12.

18 “Trio of Tigers the Fans Are Anxious About These Days,” Detroit Free Press, March 21, 1909: 17.

19 “Sidelights on the Game,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 20, 1909: 4.

20 “Why Hugh Jennings Sold Pitcher Suggs,” Evening Chronicle (Charlotte, North Carolina), September 25, 1909: 10.

21 Ibid.

22 “Suggs Flirted Himself Back to the Minors.”

23 “Base Ball Briefs,” Evening Star (Washington), May 13, 1911: 10.

24 Jack Ryder, “Sore Foot,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 8, 1910: 8.

25 Jack Ryder, “Deal,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 10, 1909: 8.

26 “Clark Says Hans Will Play,” Charlotte (North Carolina) Observer, December 25, 1909: 3.

27 Ryder, “Deal.”

28 Ibid.

29 Ryder, “Sore Foot”; “Sporting Brevities,” Evening Telegram (Elyria, Ohio), March 23, 1910: 3.

30 Jack Ryder, “Vapor,” Cincinnati Enquirer, April 11, 1910: 8.

31 “Good Players Allowed to Go,” Louisville Courier-Journal, December 10, 1911: Section 3, 4.

32 Jack Ryder, “Smashed,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 16, 1910: 8.

33 Ryder, “Vapor”; “Cincinnati Reds’ Twirler Now Most Feared Pitcher in the National League,” Mansfield (Ohio) News, July 20, 1911: 8.

34 “Suggs Has Best Bean Ball in National,” Indianapolis Star, June 22, 1911: 8.

35 Richard Scheinin, Field of Screams: The Dark Underside of America’s National Pastime (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1994), 105; James Jerpe, “Deadly ‘Bean Ball’ Keeps Players in Great Danger,” Pittsburgh Gazette Times, March 21, 1913: 10; “Playing Manager Becoming Extinct,” Arkansas Gazette (Little Rock), December 24, 1911: 10.

36 “Passes On,” Cincinnati Enquirer, October 29, 1913: 6.

37 Jack Ryder, “Leon,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 12, 1913: 8. One week later, the record was broken when Philadelphia Phillies pitcher Erskine Mayer allowed nine consecutive hits to the Chicago Cubs.

38 “Baseball Notes,” Montpelier (Vermont) Evening Argus, August 13, 1913: 6; “All the Latest Dope,” Day Book (Chicago), August 14, 1913: 10.

39 “Jinx of 1913 Is Again on the Job in Cardinal Camp,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 26, 1914: 11.

40 “Pitcher George Suggs of Reds Is Purchased by the Cardinals Club,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, October 28, 1913: 17.

41 “New Federal League A-bornin’ Here Today,” Indianapolis News, March 8, 1913: 10.

42 “Federal League Will Start War on Majors,” Los Angeles Times, October 16, 1913: Part III, 3.

43 Ibid.

44 “Jinx of 1913 Is Again on the Job in Cardinal Camp.”

45 “Federals Ready to Show Home Folk Their Play,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 9, 1914: 1.

46 “Knabe’s Men a Set of Picked Players,” Baltimore Evening Sun, April 13, 1914: 2.

47 “Suggs, Well Known Pitcher Demonstrates,” Daily Free Press (Kinston), October 14, 1914: 1.

48 “Baseball Races Close,” Baltimore Sun, September 17, 1914: 5.

49 C. Starr Matthews, “Suggs’ Record Excels,” Baltimore Sun, August 31, 1915: 8.

50 Ibid.

51 “George Suggs Dies at Kinston,” Daily Independent (Kannapolis, North Carolina), April 5, 1949: 7.

52 “Terps Twice Nosed Out,” Baltimore Sun, September 7, 1915: 8.

53 Ibid.

54 On July 27, 1915, the Daily Gate City (Keokuk, Iowa) reported that the act of intentionally walking a batter by throwing four times to first base had been used earlier in the 1915 season on at least two occasions in the Class-D Central Association. Peter Morris in A Game of Inches: The Stories Behind the Innovations That Shaped Baseball (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2010) notes that this unique type of intentional walk was employed in the major leagues by the Philadelphia Phillies in a July 9, 1924, game against the Cincinnati Reds. Shortly thereafter, National League President John Heydlerissued a directive declaring that this tactic would henceforth be called a balk.

55 W.J. O’Connor, “Former St. Louis Jumpers May Be Wished on Cards,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, February 22, 1916: 14; “Played Thirteen Innings to a Tie,” Morning Herald (Durham, North Carolina), May 2, 1916: 3.

56 “George Suggs Lost Last Game Because Lack Support, Said,” Daily Free Press (Kinston), June 3, 1916: 6.

57 Ibid.; Edwin M. Brietz, “Suggs Retires Losing His Last Game,” Twin-City Daily Sentinel (Winston-Salem, North Carolina), June 3, 1916: 7; “Couldn’t Hit Perdue’s Benders,” Nashville American, May 14, 1907: 7.

58 “George Suggs Lost Last Game Because Lack Support, Said.”

59 “Some ‘Red’ Stories,” Syracuse Post-Standard, April 20, 1910: 11.

60 “George Suggs Quits the National Game to Enter Business,” Daily Free Press (Kinston), June 1, 1916: 1; William S. Powell, Dictionary of North Carolina Biography: Volume 5 P-S (Chapel Hill, North Carolina: University of North Carolina Press, 1994), 476.

61 “Kinston Gun Club Is Off with Good Start, Ernest Webb Pres’t,” Daily Free Press, May 26, 1916: 4; Ryder, “Smashed”; typed obituary document from Suggs’s file at the library of the National Baseball Hall of Fame; “Rev. Lee White Is New President of the Kiwanis Club,” Daily Free Press, July 8, 1922: 1.

62 “Will Organize Local Amateur Baseball 9; Hope Have Game July 4,” Daily Free Press, June 16, 1919: 1; “Eastern Carolina League Lives Anew,” Daily Free Press, March 9, 1922: 1; “What Would Baseball Here Do Without This Pair of Enthusiasts?” Daily Free Press, May 31, 1922: 1.

63 David E. Dalimonte, “Kinston Has a Rich Tradition in Baseball,” Down East Wood Ducks, kinston.com/content/page.jsp?sid=t485&ymd=20100222&content_id=8111198&vkey=team3.

64 Suggs’s North Carolina State Board of Health Certificate of Death.

65 Jessika Morgan, “Meet 25 Famous Kinstonians,” Free Press (Kinston, North Carolina), kinston.com/20121031/meet-25-famous-kinstonians/310319991, October 31, 2012, accessed August 9, 2018.

Full Name

George Franklin Suggs

Born

July 7, 1882 at Kinston, NC (USA)

Died

April 4, 1949 at Kinston, NC (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.