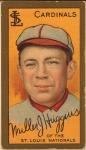

Miller Huggins

Miller Huggins was the Hall of Fame manager who led the New York Yankees to their first six American League pennants and three world championships, in the 1920s. He forged unique relationships with both Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert and their star outfielder, Babe Ruth. One newspaperman wrote, “Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert saw in Huggins a man worthy of confidence, a man hung on the cross of propaganda, which was as cruel as it was false, and as unfounded as it was detrimental to the cause of the Yankees.”1

Miller Huggins was the Hall of Fame manager who led the New York Yankees to their first six American League pennants and three world championships, in the 1920s. He forged unique relationships with both Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert and their star outfielder, Babe Ruth. One newspaperman wrote, “Yankee owner Jacob Ruppert saw in Huggins a man worthy of confidence, a man hung on the cross of propaganda, which was as cruel as it was false, and as unfounded as it was detrimental to the cause of the Yankees.”1

Huggins was also an accomplished second baseman in the Deadball Era, when he excelled despite being one of the smallest men to ever play the National Pastime. Underestimated as both a player and a manager, Huggins overcame great obstacles to excel. Baseball was his life, but ultimately the stress he experienced in it may have contributed to his premature death at age 51.

At the time, he looked (and probably felt) at least 20 years older. “Baseball is my life. I’d be lost without it,” he told sportswriter and future Baseball Commissioner Ford Frick. “Maybe, as you say, it will get me some day—but as long as I die in harness, I’ll be happy.”2

Miller Huggins was born in Cincinnati on March 27, 1878, to James T. and Sarah Huggins, who were both born in England.3 Miller was the youngest of three sons and the third of four children. He began playing baseball on semipro teams at a young age and started his pro career with Mansfield (Ohio) of the Interstate League. “I fell in love…” Huggins later recounted, “The object of my love, though, was no lady. It was, instead, baseball.”4

He played under the assumed name of Proctor (sometimes listed as Procter) in his early years, to hide his playing from his father, “a strict Methodist who abhorred frivolity and listed baseball as such,” in the words of Miller’s sister Myrtle Huggins.5 In the summer of 1900, Huggins played for one of the nation’s top sandlot teams, Fleischmann’s Mountain Tourists of upstate New York, a club owned by Cincinnati’s yeast-business family of that name.6

Huggins played for three seasons (1901-1903) with St. Paul, which became a charter member of the American Association in 1902.7 The club’s player-manager, Mike Kelley, became one of Huggins’s closest friends. During that period, Huggins found time to study law at the University of Cincinnati, gaining his degree in 1902.

“He [Huggins] was grievously handicapped by his lack of size,” wrote John Sheridan in the Sporting News. While databases list Huggins at 5’ 6” and 140 pounds, he was actually much smaller, around 5’ 1”-5’2” and 125 pounds.8 When John McGraw had a chance to acquire Huggins for his Baltimore Orioles in 1901, he declined to do so. “That shrimp?” he said to himself. “He’s too little to be of any use as a big leaguer.”9

Perhaps to compensate for his size, Huggins had a fierce and relentless determination to succeed and use his head to win. “Because he was so small and slight, he must overcome by clear thinking,” wrote Frank Graham, “obstacles that other players could surmount by force.”10

Huggins joined his hometown Cincinnati Reds in 1904 and began a 13-year career as a Major Leaguer, 11 as a regular. He led the National League in walks four times and stole 27 or more bases eight seasons. His career on-base percentage (a sabermetric number not used in his days) was a sparkling .382, with a season-best mark of .432 in 1913, at age 35.

Huggins endured the usual rookie hazing when he joined the Reds. The regulars were amused by Huggins’s crooked smile and funny batting stance. “Pipe the new mascot,” howled the 6’5” Larry McLean, as he picked up the 5’6” rookie, and held up him for the other Reds to see. “Why, kid, you’re too little to play in the big leagues. We eat guys like you for breakfast. What’s your name, Pint-Size?”

“I’m Miller Huggins,” said the rookie.

“Well, I’m Larry McLean,” said the veteran catcher.

“Yeah, well, I’ll be playing second base, and when you peg ‘em down there, you better make them good, Big Boy,” Huggins said, not intimidated.11

With his crouched batting stance and patience at the plate, he was able to out-wait and outwit opposing pitchers. In the field, he was “like a flea skating around on a greasy skillet” and earned nicknames such as “Rabbit,” “Mighty Mite,” and “Little Everywhere.”12 Huggins was a switch-hitter with virtually no power; he had nine career home runs, all inside-the-park ones.

He was so determined to gain an extra step to first base that he spent three grueling years training to work and hit left-handed. He also had a devious streak. Huggins pulled off the hidden ball trick at least eight times.13 He once handled a record 19 chances—helped by storing the game’s baseballs in a freezer to deaden them, he admitted to Ford Frick years later.14

In early 1910, Reds manager Clark Griffith traded Huggins to the St. Louis Cardinals, after a sore arm limited Huggins to 57 games the prior season.15 It was a strange move since Griffith remarked at the time, “No matter who I get for Miller Huggins, I’d be cheated…Hug is one of the best players of the game.”16

The media agreed. Sportswriter Fred Lieb wrote, “Cincinnati fans are so touchy over the deal that sent Huggins to the Cardinals that they will never forgive Griffith. Some think the proper thing would be to secure the return of Huggins and make him the manager in place of the man who traded him.”17

Griffith knew that the cerebral Huggins had managerial potential and probably saw him as a threat to his job. Griffith was fired by the Reds after the 1911 season. More than a decade later, at a banquet honoring Huggins for winning his first world championship, Reds owner Garry Herrmann said the trading of Huggins was his biggest mistake.18

The move energized the career of the 32-year-old Huggins, who had five of his best seasons from 1910 to 1914 in St. Louis.19 In 1910, he batted .265, led the league in walks, and scored more than 101 runs. In 1912, he was again put on the trading block by a manager who probably felt threatened by Huggins. In this case, the manager was fiery catcher Roger Bresnahan, but the prospective trade was nixed by the team’s owner, Helene Britton. At the end of the season, she fired Bresnahan and replaced him with Huggins, now a player-manager. There is no indication Huggins was trying to undermine either of his managers, but the move split the club into two cliques. Bresnahan’s supporters said “getting rid of the dynamic Roger and putting the little shrimp in charge was just like a woman.”20

Huggins was a quiet man with simple tastes and did not socialize much. He liked to read and play billiards and pinochle. He had business interests, including ownership of a cigar store and roller-skating rink in his hometown. Even years later, he would visit rinks on his off-days.21

He impressed people with his sharp mind and baseball “smarts.” When he took the helm of the Cardinals, Harold Lanigan of the Sporting News called him “a deep little cuss, a thorough student of the national game.”22 And just a couple of years later, New York Giants manager John McGraw said, “There is no smarter man in baseball today than Miller Huggins.”23

His first season as manager was a stressful learning experience. The Cards finished in last place with 99 losses, the club was split into cliques (pro-Bresnahan and pro-Huggins men), and Huggins almost quit.24 But he had the support of the team’s owner and through it all, he had a fine season at the plate, with a league-leading .432 on-base percentage.

In 1914 Huggins surprised the baseball world when he led the cash-strapped Cards to a third-place finish. On August 26 the team was briefly tied for first place, after winning the first game of a doubleheader. The key to the Cards’ success was the preseason eight-player trade that sent Cardinals’ star (and pro-Bresnahan) Ed Konetchy to Pittsburgh. Not only did morale improve significantly, but one of the players Huggins acquired, Jack “Dots” Miller, an underrated infielder with fine leadership skills, made a big impact.

This was the first of two seasons of the upstart Federal League, which placed a team (the city’s third, including the American League’s Browns) in St. Louis. The Cardinals’ finances became so shaky during 1914-1915 that Huggins covered some payrolls out of his own pocket.25 He also lost much of his playing talent to the rival league, including his entire starting outfield and one of his top pitchers, Pol Perritt.26

When the Federal League collapsed after the 1915 season, the Brittons refused to re-acquire any of the players they felt had deserted them. One can only wonder how high the Cardinals would have finished in the standings in the mid-Teens, had they not lost so much talent.

A bright spot for St. Louis was Huggins’ insistence on the signing of a 19-year-old Texan by Huggins’s scout and close friend, Bob Connery. Rogers Hornsby cost the club only $600; he would bat .358 for his illustrious career.

Helene Britton decided to sell her ball club after the 1916 season and promised Huggins the first chance to buy it. But when he went to his hometown to line up his financing with the Fleischmanns, Britton’s attorney convinced her to sell to a St. Louis group he was forming. Ownership consisted of many locals who bought shares in the club, which sold for $375,000.

Huggins must have been devastated. His fondest hope was to own a major-league team.27 To make matters worse, the new group hired the aggressive Branch Rickey as president before the 1917 season. He had been making all the player personnel decisions for the crosstown Browns and would assume that role with the Cardinals from Huggins.

The Cardinals’ manager handled the situation with class. When asked about the new ownership group, he said, “It is not my business. The manager is hired by the owner. I am signed for 1917 and will attend to my business for this reason.”28 Attend he did, leading the Cards to another surprising third-place finish. But, as one reporter noted, “Huggins was out, for all intent and purposes, long before the season ended.”29

The Cardinals’ manager handled the situation with class. When asked about the new ownership group, he said, “It is not my business. The manager is hired by the owner. I am signed for 1917 and will attend to my business for this reason.”28 Attend he did, leading the Cards to another surprising third-place finish. But, as one reporter noted, “Huggins was out, for all intent and purposes, long before the season ended.”29

On October 25, 1917, Yankees owner Jacob Ruppert signed Miller Huggins to a two-year contract as the club’s manager, replacing Bill Donovan. The Colonel ignored the wishes of his co-owner, Til Huston, who was in Europe with the American war effort. Huston wanted to hire his friend, Brooklyn manager Wilbert Robinson. And in 1919 and 1920, when stories of Huggins’s demise would surface in the press, Robinson would be rumored to be his successor. Yet over the years, the two New York managers remained friends.

Once again, an owner had been impressed by Huggins’s baseball knowledge. Ruppert had been taken aback the first time he met “the little fellow slouching around with a cap and a pipe” (Ruppert’s words), calling him a “grouch.” But he soon grasped the Huggins’s knowledge of the intricacies of the game and ability to organize a club.

What Ruppert may not have realized was that Huggins was aloof and brusque. Perhaps the Colonel did not care since he too had these same personality traits. “I wish I had the knack of salving newspaper men,” Huggins said a few years later. “But I haven’t, and that’s all there is to the story.”30

Damon Runyon described Huggins in his first season the Yankees’ manager, as “a serious little man. If there is any streak of humor in him, it does not make itself manifest.”31 While Runyon wrote of Huggins’s cerebral and detached nature, he also noted the skipper’s quiet presence. “Mr. Huggins has a way about him in the baseball arbor which inspires the feeling that he knows his business.”32

Huggins took over from Yankees manager Bill Donovan, one of the most beloved and gregarious of men, big shoes to fill in the eyes of many sportswriters and fans. Huggins would be quite unpopular and criticized during his first eight seasons with the Yankees.

To compound matters, the club did not win the AL pennant in his first three seasons, 1918-1920. Then, when they did win in, they lost the World Series to McGraw’s Giants—twice, 1921-1922. And when they finally won it all in 1923, many people said the Yankees only accomplished what they should have done earlier. When they collapsed to seventh place with 85 losses in 1925, there was a general feeling that Huggins had been exposed (as a poor manager) and was finished.

Much of Huggins’s difficulty lay in the fact that Ruppert and Huston were in a hurry to win and acquired established stars from other teams. Many of these men felt they did not need a manager. Sportswriter Joe Vila, one of Huggins’s few supporters in the press, noted, “With the team full of prima donnas, Huggins has the worst managerial task in the major leagues. The players dislike him and the fans ignore him.”33

One of those prima donnas was star pitcher Carl Mays, who came over from the Boston Red Sox. Hard-tempered, sometimes cold, Mays was known as a difficult personality; his last manager, Ed Barrow, had called him “a chronic malcontent.”34 While Huggins recognized the impatience of New York fans and spoke of the need to have “color” (colorful men) on the roster, he had mixed feelings, at best, about getting Mays. Huggins was seen as a protégé of league president Ban Johnson, who had suspended Mays when he walked out on his Red Sox. The battle between the Yankees’ owners and Johnson over their signing of Mays surely put Huggins in a conflicted situation.35

Another of the prima donnas was the game’s biggest star, Babe Ruth. From the start, Huggins knew that Ruth would be a “handful.” Yet he was a challenge worth acquiring. Despite the fact that Huggins embodied the Deadball Era’s “small ball” style of play, he saw the potential of Ruth to revolutionize the game, who could be called a “game-changer” in the broadest sense of the word.

It was Huggins who urged Ruppert to acquire the Boston slugger after the 1919 season. “Huggins had vision…Far-seeing judgment. He planned on a big scale,” said Ruppert. “I doubt if anybody except Huggins had the foreknowledge of just how predominant Ruth could become in the baseball world.”36

Huggins also understood what a great drawing card the Babe would be. “He pulls them in. He makes the turnstiles click,” said Huggins in Ruth’s first season in New York. The public “likes the fellow who carries the wallop. The fellow who can pound the ball is always the fellow that will win the hearts of the bleachers…Ruth appeals to everybody.”37

Ruth’s presence in the lineup let the Yankees’ owners maximize the potential of Sunday baseball, legalized in New York before the 1919 season. The Babe also made the financial risk of building the massive Yankee Stadium more manageable, with a large upside.

The irrepressible Ruth surely would have taxed any manager. One wonders how the authoritarian John McGraw would have handled the Babe—and with what results. Huggins gave Ruth plenty of leeway and explained, “If the harness were strapped too tight on Ruth I believe it would cramp his style, his personality. He is simply Babe Ruth, an institution.”38

But by providing his star player with his own set of rules (which really amounted to no rules, permitting the Babe’s late-night “activities” of partying and womanizing), Huggins was undercutting his own leadership. The approach had a disruptive effect on the club as a whole and even on the out-of-control Ruth. After the Yankees won the 1923 World Series, Huggins rationalized, “As a manager I have found Ruth very easy to handle. He is intensely ambitious and always wants to do what is best for the club. He [Ruth] has his own notions about how he ought to do it.”39

Compounding the disruptive influence of Ruth was the club’s co-owner, Til Huston, who often went out drinking with the Babe and did not back up Huggins, whom he never wanted to hire in the first place, when the manager did try to rein in Ruth. “They had reason to believe that any shackles placed on them by Huggins would be struck off by Cap [Huston].”40

When the Yankees did not win the pennant in 1920 (finishing a close third, only three games behind the Cleveland Indians), Ruth’s first year in New York, Huggins came under intensifying criticism from the harsh (then as now) New York press. Typical was the comment of veteran reporter and former ball player, Sam Crane. “Has he [Huggins] shown himself to be a leader of men, one who commands their best abilities as well as their dutiful respect?”41

After the season, Huggins suffered a nervous breakdown, which was not reported at the time and mentioned only well after it had occurred.42 And only after his death was it disclosed that he had seriously considered quitting after the 1920 season. Late in 1924 he told reporter Fred Lieb, “I will be frank with you. I would not go through those years [1920-1922] again for a million dollars…I was a sick man during a good part of the time, perhaps sicker than my friends knew, but I held on and stuck it out.”43

Huggins was a sickly man, even without the pressures of a pennant race. He suffered from neuritis, rheumatism, digestive problems, insomnia, and a generally worrisome and weak constitution. When he returned to the Yankees in early 1921, he was sidelined by blood poisoning, a serious—and potentially deadly—illness before the advent of antibiotics.

Late in the 1921 pennant race, after a heart-wrenching Yankees’ loss on September 19, the club fell out of first place. Huggins wrote out his letter of resignation and submitted it to Colonel Ruppert.44 This too was not reported at the time. Ruppert refused to accept it.

After the Yankees rallied to edge Cleveland for the 1921 pennant, only to lose a tough eight-game World Series to John McGraw’s Giants, Joe Vila hinted at what had transpired. “It was Ruppert’s words of encouragement in the darkest hours that kept Huggins from losing his nerve.”45 Besides his loyalty to Huggins, Ruppert understood as a businessman the danger of letting subordinates and outside forces dictate decisions, whether in his brewery or his baseball club.

Repeatedly late in and after the 1919, 1920, 1921, and 1922 seasons, stories surfaced that Huggins would quit or be replaced. After the 1922 season, sportswriter Warren Brown wrote that “this continuous rounding up of baseball stars have made Miller’s job next to impossible.”46

The Yankees repeated as AL champions in 1922 but were swept in the World Series by the Giants (one game was a tie, called for darkness). Late in the final game, Yankees pitcher Joe Bush loudly cursed at his manager from the mound. And after the game, a possibly inebriated Til Huston shouted in a crowded bar, “Miller Huggins has managed his last Yankee ball game. He’s through! Through!”47

When Ruppert heard about this, he was infuriated and declared, “We are for Huggins, first, last, and always.”48 A few days later, Ruppert somehow prevailed over his 50-per cent co-owner and signed Huggins for the 1923 season. The Colonel also set into motion the process of buying Huston out. When the complex deal was finally consummated in May of 1923, Ruppert sent a telegram to the travelling Yankees, making it clear who was in charge. “I am now the sole owner of the Yankees. Miller Huggins is my manager.”49

There is some evidence that it was not just Huggins and Huston who were unwilling to discipline Ruth. Ruppert himself may have played a role. He admitted at the end of the 1922 World Series, “Miller Huggins has been hampered too much by the owners of the Yankees. That includes myself. We catered to the whims of the ball players.”50

Huggins could finally relax, at least a little, now that Huston was gone. He also had another supporter in the Yankees’ front office besides Ruppert, business manager Ed Barrow. The Yankees had hired Barrow after the 1920 season (he had been the Red Sox manager). He and Huggins quickly developed a mutual respect and an understanding on how a successful franchise must be run. Early on he told Huggins, “You’re the manager, and you’re going to get no interference or second-guessing from me. Your job is to win, and part of my job is to see that you have the players to win with.”51 Barrow began assembling a strong scouting staff to do just that.

And Ruppert, to his credit and the long-term benefit of the organization, let both men operate with minimal interference from the owner’s suite.

Ruppert was rewarded with a world championship in 1923, the Yankees’ first season in Yankee Stadium. They again faced McGraw’s Giants in the World Series, and this time they prevailed with the help of Ruth’s hitting and Herb Pennock’s pitching.

One of Huggins’s greatest strengths was his ability to size up a player, his potential and limitations. In December, 1920, the Yankees made one of their many trades with the Red Sox during the 1918 to 1923 time period. While the trades were later called “the Rape of the Red Sox,” they were considered quite fair and balanced when they were made.52 The key figures in this deal were thought to be the Yankees’ infielder Del Pratt and Boston catcher and future Hall of Famer Wally Schang.

But Huggins was most interested in Boston pitcher Waite Hoyt, even though he had won only four games and had been hampered by injuries and his temperament. “Young Hoyt is a pitcher of infinite promise,” he declared. “I expect great things of him.”53 The future Hall of Famer would win 157 games for the Yankees.

Pennock was another example of Huggins’s personnel skills. When he acquired the lefty after a 10-17 1922 season with the Red Sox, the few people who noticed the trade panned it. In New York papers, it was called “the worst trade the Yankees ever made,” in which they had been “gypped,” with Huggins a “sap” for making such a deal.54 Pennock would also go on to a Hall of Fame career and win 162 games as a Yankee.

And as early as 1927, Huggins wanted to acquire yet another Red Sox pitcher who seemed to be showing little, Red Ruffing.55 The Yankees would not acquire him until 1930, after he had posted a 39-96 record in Boston. He too would go on to a Hall of Fame career, with 231 wins for New York.

Few players that Huggins released or traded excelled elsewhere. One notable exception was catcher Muddy Ruel, who went to Boston in that Hoyt deal. (Huggins thought he was too small to be an effective backstop.) Another was pitcher Urban Shocker, whom he traded soon after he took over the Yankees, when he was advised that Shocker was a troublemaker. The pitcher went on to star in St. Louis, and Huggins reacquired him seven years later.

Huggins looked for toughness in his men. “Give me the hard, relentless type of player, and you can keep the nice ones,” he told Frank Graham.56 Huggins also spoke almost endlessly about “disposition,” that he could not tell much about a player until he knew his disposition. “I want to know how he’ll act when the hits are no longer going safe.”57

In 1923, an awkward 20-year-old first baseman made his debut with the Yankees. Huggins would show great patience and nurture the youngster, Lou Gehrig. “He’s the most patient manager I ever knew. He stuck with me and encouraged me and helped me,” said Gehrig a few years later. “He is the best teacher I ever had the privilege of being with.”58

After the 1923 season, Huggins dealt the unwanted Carl Mays to his old owner, Garry Herrmann of Cincinnati. Huggins knew Mays could still pitch; he would win 20 games for the Reds in 1924 and 19 in 1926.But Huggins and Mays had a deep personal animosity, the details of which remain unclear.

Huggins bore Mays immense animosity – refusing to pitch the submariner and taunting him when Mays asked why. Some writers have speculated that Huggins blamed Mays’ pitching collapses in two games in the 1921 World Series for the Yankees losing the championship. Mays deliberately ignored signs and managerial orders on pitch selection. It was rumored that Mays “threw” the games, at the behest of gamblers. That was most likely not the case and nothing was ever proven and, but Huggins was furious all the same. Years later Fred Lieb wondered how such a “kindly gentleman” could carry such a “deep hatred.”59

The Yankees fell just short of the 1924 pennant. “A ball club which has won several championships cannot arouse itself to the same extent as a team winning for the first time,” said Huggins after the season.60 Yet he made few changers going into 1925. As much as Huggins recognized the need to introduce new talent, he was human—and intensely loyal to the core that had won three pennants for him.

This was the year that Babe Ruth collapsed after spring training and did not return to the lineup until June 1.He never hit his stride; neither did the Yankees. The result was a disastrous season, with a 69-85 record. It was also the year that Ruth almost threw Miller Huggins off a moving train.61

When stories began appearing in the papers that season that Huggins would be replaced, he fought back. “I’m going to stick, and for a long time too. I love baseball and wouldn’t know what to do with myself if I got out of the game.”62 And once again, Jacob Ruppert stood resolutely behind his manager.

1925 was also a defining season for Huggins and the Yankees. He made some difficult and probably painful decisions, including benching veteran shortstop Everett Scott, who had played in a record 1,307 consecutive games, catcher Wally Schang, and first baseman Wally Pipp (replaced by Gehrig). But his most dramatic action was suspending Babe Ruth and fining him a whopping $5,000 on August 29.

The immediate stressor that caused the move was a ninth-inning drama in Chicago on August 27, with the Yankees down a run, runners on first and second and nobody out. With the Yankees down a run, Huggins ordered the Babe to bunt – he was actually good at it – and Ruth ignored the sign, drilling a hard liner that generated a double play.63

Huggins realized he had to come down hard on the carousing Ruth, for the sake of the club’s future as well as the Babe’s. Damon Runyon’s New York American reported that Huggins had “compiled a formal chart embracing four years of insubordinate acts” by Ruth. The article went on to say that Huggins had been lobbying for permission to discipline the slugger for almost a year.64 With the Yankees’ 49-71 record, Ruth’s .266 batting average, and the season long gone for both team and player, Huggins and the Yankees could now afford to lose Ruth for an extended period of time.

A fuming Huggins rode the train by himself with his floundering team to St. Louis. There, Ruth arrived late before the first game, and the Yankees fell, 1-0, for their seventh straight loss. “Ruth will have to realize that the club is bigger than he is.”65 He added, “Patience has ceased to be a virtue.”66

Huggins phoned Barrow in New York to get his bosses’ backing, and they provided it. When the Yankees took the field for batting practice in St. Louis on August 29, all hands were there, except Ruth, who again was tardy. Huggins sat on a clubhouse bench, smoking his pipe, waiting for the Bambino, who burst through the door, and said, “Sorry, Hug, I had some business to attend to.”

The dialogue that followed became baseball legend, although the precise words vary based on the memories of those who were present (which in some accounts included that day’s starting pitcher, Waite Hoyt, and in others was pitcher Bob Shawkey) and the re-creation of writers. “No use putting on that uniform,” Huggins said. “You are not playing.”

“Now what’s the matter?” asked the frowning Ruth.

“I’ll tell you, Babe, I’ve talked it over, and I’ve come to the decision you’re fined $5,000 for missing curfew last night and being late today. You’re fined and suspended.” Huggins said, adding that traveling secretary Mark Roth had Ruth’s train ticket back to New York.

“$5,000?” Ruth roared. “$5,000? Who the hell do you think you are?” Ruth let out a stream of obscenities and warned Huggins he “would never get away with this,” adding, “If you were even half my size, I’d punch the s**t out of you.”

Huggins shot back, “If I were half your size, I’d have punched you…Before you get back into uniform, you’re going to apologize for what you’ve said, and apologize plenty. Now go on. Get out of here.”

Ruth stormed off, yelling, “I’ll never play another game for you! I’ll go to New York and see Jake. You don’t think he will stand for this, do you?”67

The Babe expected Ruppert would reverse Huggins’s moves. Ruth met with Ruppert behind closed doors at the Ruppert Brewery and emerged chastised and subdued. In a “moment of truth” for the Yankees’ organization, Ruppert backed up his manager, saying Ruth could quit if he wanted to do so and that the matter was in his manager’s hands.

Next day, Ruth went to Yankee Stadium, asking Huggins if he could suit up. Huggins responded, “Not today. Call me Friday afternoon.”68

Huggins kept his superstar hanging for another day, refusing to talk to him. Then he phoned the slugger, and Ruth apologized. Huggins let him put on a uniform and take batting practice on an off-day, but would not let him play. Ruth did so. Huggins ordered Ruth to meet the team at Grand Central Terminal to join the Yankees on their off-day for practice, for a road trip to Boston.

Ruth was right on time, and said, “Well, Hug, I’m here.”

“Yes, I see,” said Huggins. “I’ve decided to accept your apology and lift the suspension. You will not play today, but you can accompany the team to Boston. The $5,000 fine stands.”

“All right, Hug,” Ruth said, smiling. “I’ll be there.”69

In Boston, Ruth was the first one dressed and on the field, and in his second day after returning to the lineup, he smacked four hits in a doubleheader sweep over Boston, including a home run. When the Babe returned to the bench after the home run, Huggins greeted him with a smile. Next day Ruth went four for four with two doubles—for a total of nine hits in 18 at-bats since his return. By season’s end, Ruth raised his batting average to .290. Ten of his season’s 25 home runs came after his return.

The suspension marked a fundamental change in the relationship between Huggins and Ruth. After that, Ruth recognized that even he could not ignore team rules; he gained respect for his manager and seemed to regard Huggins as something of a father figure.

The showdown also had a profound impact on the Yankees’ organization. So often sports franchises take the easy way out and fire the manager because it is easier than “firing the team.” When Huggins told Ruppert and Barrow that summer that he could no longer get reactions from his listless team, Barrow’s reaction was, “Get rid of them. We’ll get a new team.”70 And Jacob Ruppert backed them up.

Huggins, who never married, lived with his spinster sister and closest confidante, Myrtle. He wistfully spoke of his loneliness, with more of a longing for a son he could provide for than for a wife. “I could give him so many things that I didn’t have…Money doesn’t mean much, unless you have someone to spend it on.”71

One thing he did spend money on was the purchase of one-third stake in the minor league St. Paul Saints of the American Association. When his scout and close friend, Bob Connery, acquired that club in early 1925, Huggins joined him, as a silent partner. This investment was not publicized in his lifetime. When the Saints fell upon hard times during the Depression, late in 1934 Connery sold the team at a substantial loss, which impacted Huggins’s beneficiary, his sister Myrtle.72

Miller and Myrtle continued to live in Cincinnati in the offseason, even after he took over the Yankees. But in the early 1920s, they made St. Petersburg, Florida, their home. Huggins had become enamored of the city, probably because of its weather, laid-back pace, and fishing opportunities. He had visited it on the way to Cuba in 1908, where the Reds played exhibition games after the regular season. He invested quite heavily in Florida real estate and most of all enjoyed languishing in a fishing boat in the bay. He soon took up another sport, golf, which he grew to love.

The Yankees moved their spring training from bawdy New Orleans to St. Petersburg in 1925, which gave Huggins an additional month “at home.”

Publicly, Huggins was a colorless man who provided few choice quotes for sportswriters. After the Yankees lost the 1921 World Series, he explained what had happened. “They won. We lost. There you have it in four words, and that’s all there is to the story.”73 When asked about the prospects for the second half of the 1925 season, he replied, “We shall see what we shall see.”74

Little was expected of the Yankees in 1926. Ruth appeared to be finished (an “old” age 31); typical was the comment of Hugh Fullerton. “It is doubtful whether he can last through a hard season.”75 The club had two rookies in the middle infield, Tony Lazzeri and Mark Koenig, and youngsters in center field and at first base, Earle Combs and Lou Gehrig. The New York Times called Huggins a “baseball Bolshevik” for “betting the roll on flaming youth.”76

Syndicated columnist Westbrook Pegler ripped into Huggins that spring. “There is no evidence that he matters enough to deserve hostility…They aren’t a team; they’re just a lot of ball players who think their manager is a sap.”77

The Yankees stunned the baseball world by winning the 1926 pennant. What most observers had forgotten (or had not realized in the first place) was that when Huggins had managed the Cardinals, their limited budget required that he develop young talent, which he did with great skill and satisfaction. Now he did the same with the Yankees.

The talent Ed Barrow was acquiring came from the minor leagues; they were also what “nice young men,” most of whom focused on the game and not second-guessing their manager or nighttime partying. Mark Koenig, an insecure player Huggins nurtured, made a revealing comment and perhaps the ultimate compliment when he said of Huggins, “He made you feel like a giant.” Koenig added that the stern and unyielding Barrow “could make you feel like a midget.”78

Huggins sold off his real estate holdings that spring, just in advance of the collapse of the Florida land bubble, triggered by the devastating Miami hurricane that September. After winning 16 straight games at the end of spring training, that Yankees replicated that streak in May-June to jump out to a big lead they never surrendered. Babe Ruth was a big surprise: Determined to return to star status, he worked hard to get into shape and lost more than 40 pounds before the 1926 season. He hit 47 home runs, with a .372 batting average and an OPS of 1.253. The Yankees lost a taut seven-game World Series to Huggins’s old team, the Cardinals, led by player-manager Rogers Hornsby, a duel punctuated by Babe Ruth’s four home runs and Grover Cleveland Alexander’s gritty pitching.

Outfielder Bob Meusel and pitcher Waite Hoyt were two players Huggins found challenging to manage and had considered trading earlier in their careers. By 1926, he had worked out his issues with them, and they became mainstays of the Yankees of 1926 to 1928. Huggins became more skilled in applying a theory he had expressed back in 1919. “I studied the characters of my players. One system will not rule. It is impossible, because you will find temperamental players, you will find players who do not need any rules, and you will find players who insist they know more than the manager.”79

Huggins’s vindication was complete. For the first time, he received widespread recognition as a great manager. A Sporting News columnist wrote, “Seldom has a team so radically changed come out of the rut of one year to win the pennant in the next. Ask Connie Mack how hard it is to do a thing like that—but Miller Huggins has done it.”80

The season was so draining on Huggins (the Yankees were challenged by the Cleveland Indians late in the season)—he was down to 106 pounds, according to one report—that he checked into a health farm in upstate New York.81 While only 48 years old, Huggins noted, “The older I grow, the harder it gets to manage a ball club. You might think experience would help, and it does. But that’s more than offset by the steady grind.”82

Once again, he seriously contemplated quitting because of his health. And once again, the public had no idea.83

In 1927 the Yankees had one of the greatest teams and seasons in baseball history. The youngsters continued to excel—and improve. The pitchers had an ERA of 3.20. (The league average was 4.14). New York won 110 games and then swept the Pittsburgh Pirates in the World Series. Huggins used a 30-year-old rookie pitcher Barrow and his scouts had found. Wilcy Moore led the league in earned run average and appeared in 50 games, 38 in relief, a position Huggins maximized that was in its infancy.

Huggins was also an early believer in the farm system. Branch Rickey had built it for his Cardinals, as a way of replenishing his roster, rather than pay exorbitant prices for minor-league stars. But no other major-league club had followed in his footsteps. Yet in December 1927, Huggins spoke of the need for baseball teams to follow Henry Ford and own their “raw materials” to keep their costs down.84

Despite respite on the golf course and his little fishing boat, Miller Huggins could not relax. The more he won, the more he worried about how to stay on top, which he admitted was well-nigh impossible. He worried about “the law of averages” catching up with his team. In early 1928 he said, “The toughest opposition which the Yankees will encounter in the coming race will be from the Yankees themselves. It is the tendency of a successful ball club to take too much for granted and believe that it can pull itself together at any time.”85

The 1928 season was another accomplishment for Huggins. The Yankees rolled to a 13½–game lead by July 1, only to see the Athletics climb into first place in early September. “When you are so far in front, folks expect so much of you. Some of the players are bound to get careless. It’s no safe thing, that big lead,” he said in early July.86 Huggins gave an emotional speech to his men before a crucial doubleheader with Philadelphia on September 9. The Yankees swept it, in front of an enormous Yankee Stadium crowd, and marched on to the pennant.

Huggins once observed that championship teams often think they are better than they really are. When they begin to lose, they don’t know what to do. “That’s when the manager has to step in and hold the wires. That’s when the players depend on the manager more than the manager depends on the players.”87

In the second half of the 1928 season, the Yankees faced a slew of injuries, which shelved pitchers Pennock and Moore and limited the play of Lazzeri and Combs, among others. Frank Graham noted that the team was held together with pins and wires.88 They still won the pennant and then swept the Cardinals in the World Series, behind Lou Gehrig’s four home runs and Babe Ruth’s three home runs and .625 batting average.

After the season, the Yankees came under criticism for being too powerful. “Break up the Yankees” was the rallying cry. Both Ruppert and Huggins aggressively responded to such calls. Ruppert explained that New York City expected only the best, and he would have it no other way. The Colonel played to win, whatever the arena.

Huggins, like his owner, wanted to win as much as possible. “It is our desire to have a pennant winner each year indefinitely. New York fans want championship ball, and the Yankees can be counted on to provide it. We are prepared to outbid other clubs for young players of quality.”89 Ruppert could not have said it better.

The irony is that while losing almost made Huggins physically ill, his striving to win took a tremendous toll on his weak body. The Yankees fell behind the Athletics early in the 1929 season and were unable to make a pennant race with the emerging Philadelphia dynasty.

Huggins showed up at Yankee Stadium with a red blotch under his left eye, which unnerved coaches and players. “Go see a doctor because I have a red spot on my face? Me? Who took the spikes of Frank Chance and Fred Clarke?” he retorted.90

On September 15, the Yankees faced the Cleveland Indians at home and suffered two blows: Huggins with the infected and painful carbuncle on his cheek, and Waite Hoyt pulled from the game after Joe Hauser smacked a three-run homer. Huggins, shining a heat light on his carbuncle, asked Hoyt how old he was. Hoyt said he’d just turned 30.

“Tomorrow, go down and get your paycheck. You’re through for the season. You just weren’t in shape. Get in good shape this winter, come down next spring and have the year I know you can have,” Huggins said.91

Everybody could see Huggins was exhausted—a young Yankee shortstop named Leo Durocher, a Huggins favorite, pleaded with his manager to take the rest of the season off—and a few days later, a run-down and worn-out Huggins left the team, and went to St. Vincent’s Hospital in New York’s Greenwich Village, with a bacterial skin infection on his cheek. It spread through his body, blood transfusions did no good, and he died just a few days after he entered the hospital. Eerily, he became the fourth Yankees’ manager who died prematurely in the 1920s.92

The little manager’s funeral took place at the Church of the Transfiguration, better known as the “Little Church around the Corner,” on Friday, September 27. All baseball games in the American League were cancelled that day.

Lou Gehrig told reporters, “I’ll guess I’ll miss him more than anyone. Next to my father and mother he was the best friend a boy could have. . . . He taught me everything I know.” 93 Ruth cried and told reporters, “You know what I thought of him, and you know what I owe him.”94

Recognition rolled in from across the baseball world, yet Huggins was not inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame until 1964. Jacob Ruppert, the owner who stood resolutely behind him, was not voted in until 2013, 49 years later. Both men operated out of the spotlight that shone on their star players.

On May 30, 1932, the Yankees began a tradition that has continued to this day, by unveiling a monument by the center field flagpole, honoring their manager. Ironically, the Yankees could never retire his number because he never wore a uniform number.

In the Yankees’ comeback season of 1926, Huggins said, “Baseball is a funny game. You can cuss it and drive it out of your mind tonight, and tomorrow morning you’re wrapped up I it again and eager to get to the ballpark.”95

After Huggins led the Yankees to their first pennant in 1921, Damon Runyon wrote, “You can buy the various parts of the finest automobile in the world, but what good are they unless you have a man who can properly assemble them?…He is entitled to all the credit and the glory that goes with the leadership of a pennant-winning ball club. He is entitled to an apology from those who have belittled his efforts.”96

Steve Steinberg and Lyle Spatz have written a book on Jacob Ruppert and Miller Huggins, “The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees” (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2015.) This BioProject biography and that book draw on similar sources, with more detail in the book. But a number of the quotes in this biography do not appear in the book.

Last revised: May 17, 2022 (zp)

Notes

1 Frank F. O’Neill, “Recognition for Huggins,” New York Sun, January 26, 1924.

2 Ford Frick, New York Evening Journal, September 25, 1929.

3 For years databases listed his birth year as 1880. Some still list 1879. It was not unusual for ballplayers of the early 20th century to lie about their age.

4 Miller Huggins, “How I Got that Way,” New York Evening Post, October 2, 1926.

5 Myrtle Huggins, as told to John B. Kennedy, “Mighty Midget,” Collier’s, May 24, 1930, 18.

6 The Fleischmann brothers were part-owners of the Cincinnati Reds, and one of them, Julius, was the city’s mayor from 1900 to 1905.

7 In 1901, St. Paul was in the Western League.

8 Myrtle Huggins said he weighed only 125 pounds in “Mighty Midget.” Henry Pringle wrote that he was “only an inch or so above five feet” in “A Small Package,” New Yorker, October 8, 1927, 25. In his life story, Huggins wrote that he weighed about 120 pounds most of his life.” “Serial Story of his Baseball Career, Chapter XIV, January 29, 1924.

9 William P. Hanna, “Home Run Rule Should be Changed by Owners,” New York Herald, January 17, 1921.

10 Frank Graham, “Huggins an Ideal Leader,” New York Sun, June 16, 1928.

11 “Pipe the New Mascot,” New York Evening Journal, September 28, 1929.

12 Cincinnati Enquirer, April 3, 1904. Teammate Larry McLean gave him the latter name.

13 Bill Deane, Finding the Hidden Ball Trick: The Colorful History of Baseball’s Oldest Ruse (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015), 48. In Deane’s research, only one player had more HBT’s than Huggins, Bill Coughlin with nine. Deane, Finding the Hidden Ball Trick, 12.

14 September 17, 1902, Sporting News, September 27, 1902. Ford Frick, “Huggins Born 49 Years Ago; Starred with Cardinals,” New York American, September 25, 1929.

15 Huggins, outfielder Rebel Oakes, and pitcher Frank Corridon went to St. Louis in exchange for pitcher Fred Beebe and infielder Alan Storke.

16 Clark Griffith, “I’ll be Cheated When I Trade Hug, “Cincinnati Times-Star, February 2, 1910.

17 Frederick G. Lieb, The St. Louis Cardinals (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1944), page 43.

18 “Early Days of Huggins Recalled,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 26, 1929.

19 Huggins had five of his six highest on-base percentages these years.

20 Frederick G. Lieb, The St. Louis Cardinals (New York: G.P. Putnam, 1944), page 49.

21 John Kieran, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, September 27, 1929.

22 Harold Lanigan, “Stove League Fuel,” Sporting News, November 21, 1912.

23 John McGraw, “McGraw Praises Huggins; Brainy Manager, He Says,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, March 7, 1915.

24 “Huggins will Quit if Team Doesn’t Rally, Friends Say: Little Boss Discouraged,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, July 12, 1913.

25 “Mound City Writers Give Huggins High Praise as He Goes,” Sporting News, November 1, 1917, and Sid C. Keener, “Huggins, Manager of a Million-Dollar Franchise, Played Hookey from Law School to Become Ball Player,” St. Louis Times, May 17, 1917.

26 Outfielders Rebel Oakes, Steve Evans, and Lee Magee. Perritt was snatched by the Giants’ John McGraw, a deal forced on Huggins because Perritt would have otherwise jumped to the Federal League. Huggins also lost another top pitcher, Slim Sallee, to McGraw, when Sallee announced he was “retiring” to his Ohio farm.

27 Dan Daniel, as told to Bob Broeg, Sporting News, July 29, 1978, and Bill Slocum, “Miller Huggins, As I Knew Him,” New York American, October 4, 1929.

28 Sid C. Keener, “’We Will have the $25,000 Option to Buy the Cardinals by Saturday,’- Jones,” St. Louis Times, March 2, 1917.

29 Joe S. Jackson, “Inside Stuff,” Detroit News, October 26, 1917.

30 F. C. Lane, “The Man who Led the Yankees to their First Pennant,” Baseball Magazine, December 1921, 595.

31 Damon Runyon, “Th’ Mornin’s Mornin,’” New York American, June 12, 1918.

32 Damon Runyon, “Th’ Mornin’s Mornin,’” New York American, April 5, 1918.

33 Joe Vila, 1923 Reach American League Guide, 87.

34 Tom Meany, The Yankee Story (New York: EP Dutton, 1960), 29-30.

35 John B. Sheridan, “Behind the Home Plate,” Sporting News, April 15, 1921, and Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 17 and 27, 1921.The author has never found a statement in any New York paper in which Huggins spoke positively of Mays or the Mays trade, when he joined New York.

36 Jacob Ruppert, “The Ten Million Dollar Toy,” Saturday Evening Post, March 28, 1931.

37 “Ruth Hero where Once Cobb Ruled,” Sporting News, August 12, 1920.

38 Miller Huggins, “Serial Story of his Baseball Career,” Chapter XXIV, San Francisco Chronicle, February 9, 1924.

39 Miller Huggins, “Serial Story of his Baseball Career,” Chapter XXIII, San Francisco Chronicle, February 8, 1924.

40 Frank Graham, The New York Yankees (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1948), 63.

41 Sam Crane, “Collapse of Pitching Staff Sends Yanks into Slump,” New York Evening Journal, September 20, 1920.

42 Frederick G. Lieb, “Yankee Manager Comes to Town,” New York Evening Telegram, November 29, 1921, and Will Wedge, New York Sun, May 20, 1924.

43 Frederick C. Lieb, “Huggins will Stay with Yankees Indefinitely,” New York Evening Post, December 26, 1924.

44 Frederick G. Lieb, New York Evening Telegram, December 12, 1922, and Ed Van Every, “Will Babe Ruth Manage Yanks?” New York Evening Mail, October 24, 1921.

45 Joe Vila, “Ruppert and Barrow Ignore Campaign against Huggins,” Sporting News, November 3, 1921.

46 Warren W. Brown, “Huggins Earns Cheers from Yanks Fans,” New York Evening Mail, September 4, 1922

47 Frederick G. Lieb, “41 Years Ago They Played Tie Contest and Lost Four,” Sporting News, October 19, 1963.

48 Huggins May Stay as Yanks Manager,” New York Times, October 10, 1922, and “Huggins will Manage Yankees Next Season,” New York Tribune, October 10, 1922.

49 Frank Graham, The New York Yankees, 92.

50 Sid C. Keener, St. Louis Times, October 10, 1922.

51 Ed Barrow, with James M. Kahn, My Fifty Years of Baseball (New York: Coward-McCann, 1951), 110.

52 Steve Steinberg, “The Curse of the . . . Hurlers?” Baseball Research Journal, SABR, No. 35, 2007, 63-73.

53 New York Evening Mail, April 9, 1921.

54 Steinberg, “The Curse of the . . . Hurlers?” 71.

55 Dan Daniel, “New York Evening Telegram, December 10, 1927.

56 Frank Graham, “Prefers Old Type of Player,” New York Sun, June 22, 1926.

57 Fred Lieb, “Cutting the Plate,” New York Evening Post, September 14, 1927.

58 “Hug Class of Bunch as Pilot, Says Gehrig,” Gehrig’s Life Story, Chapter 26, New York American, September 28, 1927.

59 Fred Lieb, Baseball as I Have Known It (Lincoln, NE: Bison Books, 1996), 132.

60 Fred Lieb, “Mental Disintegration Huggins’ Fear,” New York Telegram and Evening Mail, April 18, 1925.

61 Steve Steinberg and Lyle Spatz, The Colonel and Hug: The Partnership that Transformed the New York Yankees, (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2015), 231-232.

62 Joe Vila, “Youngsters Instill New Spirit into Wavering Ranks of Yanks,” Sporting News, June 18, 1925.

63 Robert W. Creamer, Babe: The Legend Comes to Life (Penguin Books, 1983), 294. Ruth brought up this incident when he met with reporters after he was suspended.

64 “Huggins Will Cite Four Years of Troubles,” New York American, September 1, 1925.

65 “Ruth Sees Ruppert: Offers Olive Branch,” New York Times, September 2, 1925.

66 “Ruth Fined $5,000; Costly Star Banned for Acts Off Field,” New York Times, August 30, 1925.

67 Dave Anderson, “Sports of the Times,” Miller Huggins file at the A. Bartlett Giamatti Library, Cooperstown, NY; Graham, Frank, “All-Time All Stars,” Signet, 1977, 184; Leigh Montville, The Big Bam (New York: Broadway Books, 2006), 207-208, and Creamer, Babe, 292-301.

68 Montville, The Big Bam, 207-208.

69 New York Times, September 7, 1925.

70 Barrow with Kahn, My Fifty Years in Baseball, 142.

71 Bill Corum, “Sports,” New York Evening Journal, March 9, 1927.

72 Miller Huggins estate documents, relating to St. Paul Saints sale, Steve Steinberg Collection.

73 F. C. Lane, “The Man who Led the Yankees to their First Pennant,” 595.

74 “Yankees Play Browns in 2 Games Today,” New York Times, July 7, 1925.

75 Glenn Stout and Richard Johnson, Yankees Century (Boston: Houghton-Mifflin, 2002), 116-117.

76 James R. Harrison, “Baseball,” New York Times, March 8, 1926.

77 Westbrook Pegler, “Yankees Pretty Fair Ball Players, but not Ball Team,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 14, 1926.

78 John Mosedale, The Greatest of All: The 1927 Yankees (New York: Dial Press, 1983), 61.

79 Sid C. Keener, “Huggins, Manager, Manager of a Million-Dollar Franchise,” St. Louis Times, May 17, 1919.

80 “Casual Comment,” Sporting News, August 12, 1926.

81 Steinberg and Spatz, The Colonel and Hug, 253.

82 F. C. Lane, “Huggins and Harmony,” Baseball Magazine, November 1926, 535.

83 Bill Slocum, “Miller Huggins, as I Knew Him,” New York American, October 4, 1929.

84 James R. Harrison, “Sports of the Times,” New York Times, December 11, 1927.

85 Bill Slocum, New York American, March 28, 1928.

86 Sporting News, July 14, 1928.

87 Arthur Frommer, Baseball’s Greatest Managers (New York: Franklin Watts, 1985), 111.

88 Graham, The New York Yankees, 146.

89 “Hug Guards Yanks against Let-Down,” Sporting News, August 4, 1927.

90 Babe Ruth, as told to Bob Considine, The Babe Ruth Story, Signet, 1992.

91 Marty Appel, Pinstripe Empire, Bloomsbury, 2012, Page 164.

92 Bill Donovan (1923, age 41), Frank Chance (1924, age 48), and George Stallings (1929, age 61).

93 Appel, Pinstripe Empire, Page 165.

94 Creamer, Babe, 347.

95 F. C. Lane, “The Man who Led the Yankees to their First Pennant,” 595.

96 Damon Runyon, Editorial, New York American, October 3, 1921.

Full Name

Miller James Huggins

Born

March 27, 1878 at Cincinnati, OH (USA)

Died

September 25, 1929 at New York, NY (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.