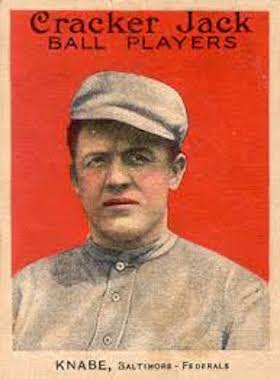

Otto Knabe

A “short, stocky, active, aggressive” second baseman, Otto Knabe teamed with shortstop Mickey Doolan to provide the Phillies with one of the most notorious double-play tandems of the Deadball Era.1 After seven years in Philadelphia, Knabe jumped to the Federal League in 1914 to lead the Baltimore Terrapins. But in Baltimore and two later minor league stops, the relentless drive that defined his on-field play may have exhausted the teams he managed. Knabe’s post-playing days were also marked by gambling controversies.

A “short, stocky, active, aggressive” second baseman, Otto Knabe teamed with shortstop Mickey Doolan to provide the Phillies with one of the most notorious double-play tandems of the Deadball Era.1 After seven years in Philadelphia, Knabe jumped to the Federal League in 1914 to lead the Baltimore Terrapins. But in Baltimore and two later minor league stops, the relentless drive that defined his on-field play may have exhausted the teams he managed. Knabe’s post-playing days were also marked by gambling controversies.

Franz Otto Knabe was born on June 12, 1884, in Carrick, Pennsylvania, then a town south of Pittsburgh, now a neighborhood within the city itself. His father, Adam, had emigrated from Germany, and worked as a coal mine foreman. His mother, Sarah, was of Pennsylvania stock. Otto was the fourth of nine children.

Knabe played for multiple Pittsburgh-area amateur and semipro teams as a youngster, most notably the Beltzhoover Athletic Club. Colorado Springs of the Class A Western League signed him in early 1905. As a hustling (“takes as many chances as anyone in the league in getting to a base”) utility player, he demonstrated enough potential for the Pittsburgh Pirates to draft him that September.2 Knabe made his major league debut on October 3, and played several games at third base. Suggesting “the making of a fast player” but “not yet up to league form,” Pittsburgh optioned Knabe to Toledo of the Class A American Association after the 1905 season.3

With the Mud Hens in 1906, Knabe played second, and impressed some onlookers as being “as good a fielder as [then Pittsburgh second baseman] Claude Ritchey and a better batsman.”4 In September, Pittsburgh recalled Knabe from Toledo. But in December the Pirates dealt Ritchey to the Boston Beaneaters for veteran second sacker Ed Abbaticchio. Knabe was less of a necessity. Pittsburgh, desiring pitcher Howie Camnitz from Toledo, cut a deal to trade Knabe outright for Camnitz. To do so, the Pirates had to ask for waivers on Knabe. Across the state, new Phillies manager Billy Murray inherited 40-year-old Kid Gleason as a starting second baseman. Murray foiled Pittsburgh’s plans, claiming Knabe for the waiver price.5

Prior to the May 18, 1907, game against the visiting Reds, Gleason was injured in batting practice. Murray inserted Knabe into the starting lineup. Philadelphia won eight of their next nine. For the next seven years, Knabe was the Phillies’ second baseman, playing 931 games for the team at the position, a franchise record that stood until Tony Taylor eclipsed it in 1969.

One contemporary recalled Knabe having “arms like a blacksmith” while another described his back as looking “like the cornerstone of a country post office.”6 Not “the fastest man, straightaway, on the Phillies,” Knabe was nonetheless thought “the quickest in action.”7 “The little fellow is not as artistic as some infielders,” noted another admirer, “but he is a live wire and it is impossible to keep him out of every play that he can reach.”8

Knabe was paired with the taller, thinner Doolan, providing the Phillies with a memorable “Mutt and Jeff” double-play tandem.9 “It’s a pretty thing to see Doolan and Knabe working a double play,” stated an onlooker in 1910, “either of them can take the other’s quick throw and pivot for the chuck to first in record time.”10

In a June 26, 1911, 5-0 victory over visiting Boston, Knabe made the play of his career. The Rustlers’ Johnny Kling led off the third by smashing “a fast grounder which shot past second base a few feet on the right field side of the bag. Knabe started in pursuit with the crack of the bat, running sidewise out towards center field in order to get in line with the ball. At the same time Doolan ran over and stood on the middle sack. When about 25 feet back of second base and on the full run, Knabe shot out his right hand and the ball was a prisoner. Otto clutched the horsehide for a fraction of a second, just long enough to get a grip, and while still plunging away from the diamond, tossed the ball to Doolan who, making one of his lightning-like half-turns, shot it to [first baseman Fred] Luderus. Kling was out by a good step, although he did not loaf going down the line.”11

Knabe and Doolan were also likely the roughest middle infield combination of their era. Doolan, Philadelphia sportswriter (and ex-Phillie) Stan Baumgartner recalled, had a “devastating underhanded throw on double plays” that could catch a baserunner in the ribs. “Knabe had a fast overhand toss that shaved the chin or knocked off the heads of incoming runners who did not duck quickly.”12 Upon coming into second, a runner might be blocked, have his feet trampled, face ground into the dirt, hands spiked, or ribs smashed with a venomous tag. The duo, Edd Roush remembered, would “cup their gloves around their mouths and call across the bag as soon as I reached first. And they would really divide me up—in two parts.”13 Once, the Cardinals’ Rebel Oakes announced he was seeking vengeance for the spike wounds the Phillies had inflicted upon his teammates. “Oakes got on first and started down to second,” longtime Philadelphia sportswriter Jim Nasium—a pen name used by Edgar Wolfe—recounted. “As he slid for the bag with his spikes high, Knabe grabbed one of his feet and gave his leg a terrific wrench. Doolan, taking the throw, hit him on the chin with the ball and knocked him cold.”14

“Slickest umpire-teasers in the business and punished rarely,” a Pittsburgh observer griped of the Phillies’ double-play combo.15 But Knabe’s antics earned him a couple dozen ejections and several suspensions over his career. In addition to baiting umpires, he mercilessly taunted opponents with “a choice assortment of refined parlor language.”16 Knabe also “did not hesitate to apply the lash to his teammates whenever they showed signs of lagging.”17 Pete Alexander recalled, as a rookie in 1911, rebuffing his second baseman’s sharp criticism. “Listen you fresh busher,” Knabe snarled, “when we get to the clubhouse I’ll show you how to talk to a regular.” After the game, the considerably larger pitcher approached Knabe and offered, “Well, I’m ready now if you want to fight.” “Oh the game’s over now,” said Knabe, dismissing the moment of battle as already forgotten.18

Despite the excesses of his game, Knabe’s intelligence and work ethic were widely admired. “The finest package of base ball in the National League for moons is that lad Knabe,” opined Joe Kelley in 1908, “He is always fighting, over on the move trying something.”19 A few years later, sportswriter Francis Richter labeled Knabe “one of the most valuable players in the profession by reason of his aggressiveness, gameness, irrepressible optimism, intense loyalty to his team, his thorough knowledge of ‘inside ball’ and his ability to apply that knowledge.”20 Even in opposing cities, his energy was infectious. “Otto Knabe is one of the game’s best cards,” a Cincinnati scribe wrote after a 1911 doubleheader. “He is so scrappy that the moment he opens his mouth every fan in the park begins to scrap with him. Sunday, after he had been kidded unmercifully … [throughout] the first game he walked to within 20 feet of the stand and surveyed the roaring multitude for two minutes without batting an eye. Much hooting, howling and kidding, but all in a good-natured way. Then Otto doffed his cap and retired to the doghouse.”21

At the plate, the right-handed Knabe produced fairly well as a rookie, with a 114 OPS+ in 1907. From 1908 through 1913, however, his OPS+ numbers languished in the 80s. Even so, he capably adapted his approach as his place in the lineup varied. In his first two seasons, he usually hit second. In 1909 he started in the leadoff spot, then down to second, before being dropped into the sixth hole. In 1910 he again predominately batted second and led off in 1911. He batted mostly fifth or sixth in 1912, then hit second in 1913. “Otto knows the sacrifice game to perfection and rarely fails to lay down a successful bunt when a base runner is to be shoved up a peg,” stated Richter.22 Knabe led the National League in sacrifice hits each season he was mostly hitting second. But when Knabe was assigned the leadoff spot in 1911, he tightened his plate discipline and his SO/W ratio improved (from 0.89 in 1910) to 0.37.

Although constrained by an underfunded local ownership group, Murray led the Phillies to first-division finishes in 1907 and 1908. But in 1909 the team sank under .500 and attendance fell by 25%. After the season, divisive sportswriter Horace Fogel was presented as the new owner.23 Cries of “syndicate” baseball, with Cubs president Charles Murphy as the suspected financer of the purchase, resulted.24 Trade rumors, with Knabe (and a pitcher to be determined later) going to the Cubs for Heinie Zimmerman, played in the press for weeks.25

Longtime Phillies catcher Red Dooin replaced Murray as manager. The trade talk receded. The Phillies slightly rebounded in 1910 to a 78-75 finish. That offseason, despite Fogel’s initial interference, Dooin obtained Hans Lobert and Dode Paskert in a major trade.26 Knabe was signed to a three-year contract at $3,000 per season. Rookie pitchers George Chalmers and Pete Alexander were recruited.

In 1911 the rebuilt Phillies finally contended. As late as July 20, the team resided in first place with a 52-32 record. But John Titus broke a leg, Sherry Magee was suspended for a month, then Dooin broke a leg as well. Philadelphia faded to a 79-73 finish. Dooin made off-season salary demands. Fogel countered by floating Knabe as a likely replacement manager. Eventually terms with Dooin were reached. The Phillies underachieved to a 73-79 mark in 1912.

Knabe was “exceedingly ambitious” and a new series of rumors fueled his aspirations in August 1912.27 This time, the Reds sought him to replace Hank O’Day as their manager.28 But Fogel was preoccupied with launching wild claims that the pennant was being fixed for the Giants, and the deal likely evaporated in the controversy. In December, with the whole of the NL against him, Fogel resigned.

William Locke assumed ownership of the team, backed Dooin, then promptly fell victim to cancer.29 The 1913 edition of the Phillies again raced out to a fine start. By June 25, Philadelphia stood in first place, 4 1/2 games ahead of the Giants, with a 38-17 record. But the team then lost 13 of 16 games over a lengthy homestand, and fell 7 1/2 games behind New York. “The players appear to have lost all of their pepper, aggressiveness, and ambition,” noted a correspondent.30 The Phillies couldn’t close on the Giants, finishing a distant second at 88-63. Locke died on August 14, 1913.

A couple minor shareholders friendly to Knabe floated his name as an alternative to Dooin. But Locke’s cousin, William Baker, assumed ownership that October and strongly backed the skipper.31 In December, Dooin proposed sending Doolan and Knabe—plus any of the pitchers save Alexander or Tom Seaton—to the Reds for Joe Tinker and Heinie Groh.32 But fast-moving events overtook the moment. The Reds named Buck Herzog as their new manager. Tinker was severing his ties to the National League to jump to the ascendant Federal League. And Otto Knabe, after seven seasons of not progressing with the dysfunctional Phillies, was following Tinker’s lead.

In November Knabe had turned down an offer to manage the Federal League’s Pittsburgh franchise. Perhaps he had used this offer to spur Philadelphia management to construct the Cincinnati deal. Or perhaps the Cincinnati deal was already in the planning stage, and Knabe favored the prospect of leading the Reds over the Feds’ Pittsburgh team. In any case, after the proposed trade washed out, Knabe was in discussions with the Feds by late December. On January 6, 1914, he signed a three-year contract, at $10,000 per season, to serve as player-manager for the league’s Baltimore franchise. Philadelphia counter-offered. Knabe flatly rejected that overture. Phillies officials then expressed no surprise at his jumping.33

Baltimore ecstatically welcomed back major league baseball, and 30,000 fans saw the Terrapins defeat Buffalo on opening day. The squad possessed better-than-average talent, thanks in part to Knabe helping to recruit Doolan and Jimmy “Runt” Walsh from the Phillies. By May 27, Baltimore had raced out to a 22-7 mark, 7.5 games ahead of the pack. But the Terrapins played only .500 baseball over the remainder of the 1914 season, eventually finishing in third place with an 84-70 record.

In part, the Terrapins’ fade was attributable to injuries and a lack of pitching depth. Another contributing factor may have been flagging morale. Pitchers Frank Smith and John Allen attempted to jump to Montreal of the International League on May 16. Smith was a valuable veteran, and a rather notorious malcontent; Allen was a semipro recruit. When their jump was rebuffed (the International League standing firm with the American and National Leagues against the Feds), Knabe backed a stiff 45-day suspension of Smith. Soon thereafter Federal League President James Gilmore rescinded this action. Smith was of slight value to Baltimore for the remainder of the 1914 season.34

Another insight into the team’s morale came from a fan’s letter to The (Baltimore) Sun on July 25. Two days earlier, when Baltimore edged St. Louis, 5-4, the fan reported Knabe chased off Harry Swacina from a foul ball the first baseman “would surely have had.” Knabe dropped the ball, made an ill-advised throw, then “angrily, within distinct hearing of all the first base fans, read a riot act to Swats.” The first baseman mouthed back, and their quarrel helped to set off a near-riot in the stands. The fan concluded that “a manager can hardly be guilty of a worse mistake than to call down publicly any player, especially in the case of a man like Swats, one of the most intense workers conceivable.”35

Excepting the addition of Chief Bender to the pitching staff, the Terrapins were mostly the same squad in 1915. The team was even less impressive in its second season. On June 8, at Brooklyn, Terrapins southpaw Bill Bailey yielded an eighth-inning grand-slam to Fred Smith. “Knabe threw his glove in the air and strode to the box to give Bailey a fine little tongue lashing.”36 The 5-3 loss dropped Baltimore to 16-27.

Knabe tried a few lineup changes, including benching himself (after a poor OPS+ of 72 in 1914, he achieved an OPS+ of 91 in 1915). But he faced a Federal League irony: many of the underachievers were tied to long-term contracts, and access to minor league resources was lacking. Attendance plummeted, a few veterans finally cut or dealt away, and the Terrapins finished in the cellar, with a 47-107 mark.

After baseball peace was achieved, the Pirates picked up Knabe in April 1916 as a possible solution to their second base needs. Yet he was out of shape and proved “not the ground coverer he used to be.” Pittsburgh released him in early June, and the Cubs signed him as a “coach and utility infielder.” Knabe played in 51 games with Chicago, his final major league playing time.37

With Richmond of the AA International League floundering in May 1917, Knabe was hired to manage and play second base. But the Virginians finished in last place. Cubs manager Fred Mitchell brought Knabe back to the majors in 1918 as a coach. Chicago won the pennant and faced the Red Sox in the World Series. From behind the third base line, Knabe and his Boston counterpart, Heinie Wagner, both verbally rode the opposition and each other. Between innings in Game Two, Knabe insulted Wagner to a breaking point, and the two coaches engaged in a “private brawl” under the Comiskey Park grandstands.38 Knabe got the better of the scrap, but the Red Sox got the better of the Cubs, taking the Series in six games.

Knabe stayed with the Cubs through August 1919. In June 1920, he took over the managerial duties for the Kansas City Blues of the AA American Association. After finishing in the cellar in 1920, Knabe drove the team to a third-place finish in 1921. But by June 1922, the team wilted under his iron will, and he was dismissed.39

After losing his job to Knabe in 1907, second baseman Kid Gleason had mentored the newcomer, and eventually emerged as one of his closest friends. For years the two partnered in running a billiards parlor in Philadelphia. After being fired from Kansas City, Knabe returned to these business interests. The pool room seems to have morphed into something else over the years. In 1937 a Pennsylvania grand jury indicted Knabe and four others for running “a sumptuous gambling casino” on Samson Street, where patrons engaged in “gambling card games, or rolling dice or betting on horses.”40 Two years later, after Phillies owner Gerald Nugent, Phillies coach Hans Lobert (who had known Knabe since the Beltzhoover lots), and others appeared as character witnesses, the charges against Knabe were cleared.41

Knabe’s possible association with gamblers had also been reported at the very height of the Black Sox scandal. First, Francis X. “Effie” Welsh, a sportswriter for the Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader alleged in a September 28, 1920, column that Knabe had been prepared to place a large pooled bet on the White Sox prior to the 1919 World Series. But before Knabe placed the bet, a ball player friend alerted him that a fix was on. Knabe investigated the matter, confirmed something crooked afoot, and reported this to Gleason, then managing the White Sox. The two quarreled, split their partnership, and Knabe placed his bet on the Reds.42

Two days after Welsh’s story, Horace Fogel surfaced to claim that, in the heated 1908 NL pennant race, five Phillies, including Knabe and Dooin, had been offered anywhere from $1,000 to $5,000 apiece to throw a key (but unspecified) series to assist the Giants. The players rejected the bribe.43

Fogel had a well-established knack for splashy stories. But Dooin immediately confirmed the 1908 incident.44 On one point Welsh’s story seems suspect. If there was any falling out between Gleason and Knabe, it was not a lasting one. When Gleason returned to Philadelphia in 1923, after retiring from the White Sox, he visited daily “his old side kick, Otto Knabe.”45 But the diary of White Sox team secretary Harry Grabiner, as presented years later by Bill Veeck, substantiates Welsh’s account that Knabe was tipped before betting on the ill-fated Series.46

Knabe ran a tavern in Philadelphia after the gambling indictment. He had married Kathryn Welsh after the 1911 season; the couple did not have any children. In 1950 he suffered two paralytic strokes, which (at least temporarily) left half his body paralyzed. On May 17, 1961, another stroke led to his death. Survived by his wife, Otto Knabe was buried in Philadelphia’s New Cathedral Cemetery.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Knabe’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following sites:

chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers/

Notes

1 Sporting Life, December 21, 1907, 3. Although Knabe was almost inevitably described as short in his era, the author was unable to find any specific contemporary listings of his height. Later in life, Knabe’s WWII draft registration card lists him as 5-foot-4.

2 “Grizzlies Win Last Home Game of the Season,” Denver Rocky Mountain News, September 8, 1905, 8.

3 A. R. Cratty, “Pittsburg Points,” Sporting Life, October 21, 1905, 14.

4 “News Notes,” Sporting Life, June 16, 1906, 10.

5 “Knabe to Return,” Toledo News-Bee, September 24, 1906, 6; “Has Knabe Been Sold?” Toledo News-Bee, December 18, 1906, 6; Veteran [pseud.], “Cutting Strings,” The Sporting News, January 1, 1907, 1; the Otto Knabe affidavit from the 1915 The Federal League of Baseball Clubs vs. The National League, et al. available via SABR.org/research/1915-Federal-League-case-files, accessed March 15, 2015.

6 Stan Baumgartner, “Miller Another Doolan with Phils?” The Sporting News, February 18, 1948, 3; “Otto Knabe, Brilliant Quaker Infielder, As Seen by Sid Smith,” Chicago Examiner, July 14, 1908, 9.

7 Francis C. Richter, “Philadelphia Points,” Sporting Life, May 16, 1908, 3.

8 “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 24, 1910, 14.

9 Baumgartner, “Miller Another Doolan?”

10 Francis C. Richter, “Philadelphia Points,” Sporting Life, September 10, 1910, 7.

11 William G. Weart, “Knabe is Shining,” The Sporting News, July 6, 1911, 1.

12 Stan Baumgartner, “Phillies Tab Keystone Kids as Future Crack Combine,” The Sporting News, September 7, 1949, 11.

13 Harold C. Burr, “Baseball—Chapman Guides for Keeps in 1946,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 9, 1945, 24.

14 Jim Nasium [Edgar Wolfe], “Billy Murray’s Death Recalls Early Dramatic Episodes,” The Sporting News, April 8, 1937, 5.

15 A. R. Cratty, “Pittsburg Points,” Sporting Life, August 13, 1910, 5.

16 “Notes of the Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 17, 1910, 8.

17 “Baseball Gossip,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 4, 1911, 8.

18 Grover Cleveland Alexander, “Alexander’s Rookie Days Were Real Rough Compared to Today,” (New Orleans) Times-Picayune, June 13, 1930, 22.

19 A. R. Cratty, “Pirate Points,” Sporting Life, August 29, 1908, 6.

20 Francis C. Richter, “Quaker Quips,” Sporting Life, July 15, 1911, 7.

21 Ros [pseud.], “Fans and Otto Knabe Have Many Wordy Battles During Contest,” Cincinnati Post, September 18, 1911, 6.

22 Francis C. Richter, “Quaker Quips,” Sporting Life, July 17, 1909, 7.

23 On Fogel, see Michael Lalli, “Horace Fogel: The Strangest Owner in Phillies History,” Philly Sports History, http://phillysportshistory.com/2011/07/06/horace-fogel-the-strangest-owner-in-phillies-history/, accessed March 15, 2015.

24 “Hot Shot—From President Johnson,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 27, 1909, 8.

25 “Zimmerman Traded to Phillies by Cubs,” Chicago Examiner, November 28, 1909, 1.

26 William G. Weart, “Philly Stirred Up,” The Sporting News, November 3, 1910, 1.

27 Rice [pseud.], “Joe Tinker Verifies His Jump to the Federal League,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, December 30, 1913, 18.

28 “Fleischmann Attempting to Get Otto Knabe to Manage Redlegs,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 11, 1912, 14.

29 On Locke, see Shane Tourtellotte, “The William Locke Centennial,” Hardball Times, http://www.hardballtimes.com/the-william-locke-centennial/, accessed March 15, 2015.

30 William G. Weart, “Extremes Kill All Interest in Philly,” The Sporting News, July 17, 1913, 1.

31 Jack Ryder, “Hopeful—Of Winning Next Time,” Cincinnati Enquirer, November 3, 1913, 8; William G. Weart, “Philly Forgets It’s a Prim Quaker Town for a Night,” The Sporting News, October 23, 1913, 1.

32 “Coombs Will Not Pitch Until July,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 23, 1913, 9.

33 For Knabe’s jumping see, “Offered Federal Berths,” Washington Herald, November 5, 1913, 10; the Otto Knabe affidavit; “Tinker Has Signed for Three Years with New Federal League,” (New York) Evening World, December 29, 1913, 2; Stanley T. Milliken, “Sporting Facts and Fancies,” Washington Post, January 6, 1914, 8.

34 For this background, see Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2009): 99-104.

35 “Letters to the Editor,” The (Baltimore) Sun, July 25, 1914, 6.

36 “Home-Run Clout by Fred Smith Wins Him a Regular Job,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 9, 1915, 22.

37 “Pittsburg Signs Otto Knabe,” The Sporting News, April 20, 1916, 1; Ralph S. Davis, “A Hopeless Note in Pittsburg’s Story,” The Sporting News, May 18, 1916, 2; Ralph S. Davis, “Callahan Gets His Eyes Open to Feds,” The Sporting News, June 8, 1916, 3.

38 Robert W. Maxwell, “Cubs Register Double Triumph Over Red Sox. Knabe Assisting Tyler,” (Philadelphia) Evening Public Ledger, September 7, 1918, 10.

39 I. E. Sanborn, “Cubs Start East to Work Off Long List of Bargain Battles,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 12, 1919, 17; “Knabe to Lead Blues,” Kansas City Star, June 20, 1920, 14; Alport Hager, “Singing the Blues,” Kansas City Kansan, June 14, 1922, 8; “A New Life for Blues,” Kansas City Star, June 15, 1922, 12.

40 “Gambler’s Rich Layout is Described,” Philadelphia Inquirer, November 9, 1939, 9.

41 “Former Phillie Star Cleared on Charge,” The (Franklin, Pennsylvania) News-Herald, November 10, 1939, 12.

42 ‘Effie’ Walsh, “White Sox Players Were Bought Out in 1919 World Series,” Wilkes-Barre (Pennsylvania) Times-Leader, September 28, 1920, 21.

43 “Gamblers Tried to Buy Local Players,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 30, 1920, 5.

44 “Phils Offered Bribes in 1908, Says Red Dooin,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 1, 1920, 19.

45 James C. Isaminger, “Mack Doesn’t Deny He’d Like to Make a Trade for Heilmann,” The Sporting News, November 25, 1923, 1

46 Note too, the mention of Knabe within the Grabiner diary in Sean Deveney, The Original Curse: Did the Cubs Throw the 1918 World Series to Babe Ruth’s Red Sox and Incite the Black Sox Scandal? (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2009): 47-48.

Full Name

Franz Otto Knabe

Born

June 12, 1884 at Carrick, PA (USA)

Died

May 17, 1961 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.