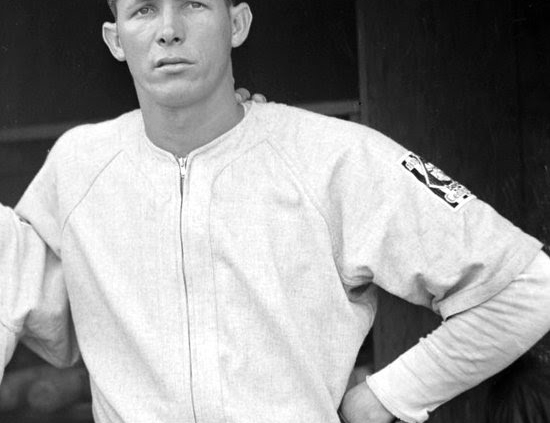

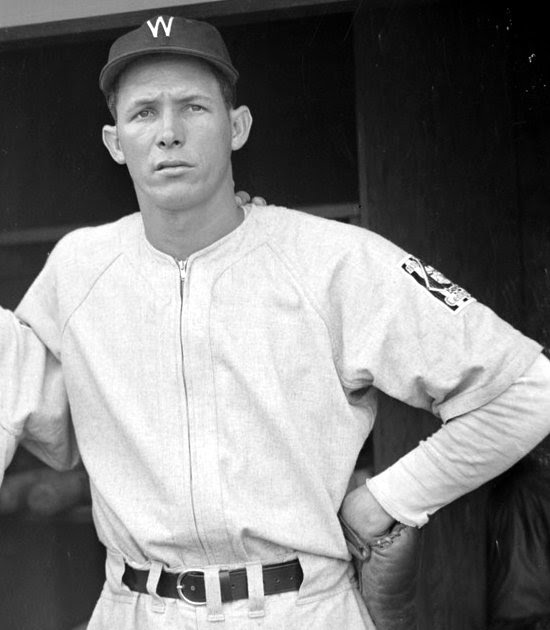

Elmer Gedeon

A star athlete in high school and at the University of Michigan, Elmer Gedeon played a handful of games for the Washington Senators in 1939. He died while flying a bombing mission over France in 1944, less than a week after his 27th birthday. James T. Taaffe, a fellow officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, and Gedeon’s co-pilot on that fateful mission, recalled the tall, slender captain as “a super gentleman.”1 Along with Harry O’Neill, Gedeon was one of two major-leaguers killed in World War II.

A star athlete in high school and at the University of Michigan, Elmer Gedeon played a handful of games for the Washington Senators in 1939. He died while flying a bombing mission over France in 1944, less than a week after his 27th birthday. James T. Taaffe, a fellow officer in the U.S. Army Air Corps, and Gedeon’s co-pilot on that fateful mission, recalled the tall, slender captain as “a super gentleman.”1 Along with Harry O’Neill, Gedeon was one of two major-leaguers killed in World War II.

Elmer John Gedeon was born on April 15, 1917, in Cleveland, Ohio. His father, Andrew Gedeon, was born in 1893, also in Ohio. According to the 1920 U.S. census, Andrew worked as a postal clerk. Elmer’s mother, Lillian (née Sacha), was born in Ohio in 1892, according to the 1900 census. All four of Elmer’s grandparents hailed from the present-day Czech Republic. It has been reported that Elmer was the nephew of Elmer Joseph “Joe” Gedeon, an infielder for the Senators, Yankees and Browns from 1913-1920.2 However, Joe Gedeon was born in California in 1893, seven months after Andrew, so Joe is certainly not Andrew’s brother or Elmer’s uncle. It is quite possible that the two ballplayers are more distant relations.

Andrew and Lillian were married in 1915. In addition to Elmer, the couple had a daughter, Audrey, who was born on May 27, 1924. The Gedeon home “stood on a hill that overlooked Brookside Park, a hub for Cleveland sandlot baseball in the 1930s.”3

As a youth, Elmer liked to ice skate on the frozen ponds of the upper Midwest. One winter day, he watched his cousin Bob Gedeon plunge underneath the ice. Years later, Bob recalled that he was struggling in frigid water “up to my neck. Elmer slid across the ice on his belly and pulled me out.”4

Elmer starred in four sports at East High School in Cleveland. He played football and basketball during fall and winter, respectively, and, as the weather warmed, he turned his attention to baseball and track. In 1935, Gedeon ran the 120-yard high hurdles in a state-record time of 15 seconds.5

As he did during high school, Gedeon competed in multiple sports at Michigan. He played first base for the Wolverines’ baseball team and both punted and ran from the backfield on the football squad. Fred Janke, a Michigan tackle and fullback, remembered Gedeon as “a very fine guy. A perfect guy. Everyone liked him. … A rather serious kid. He could kick well. They used to pull him back in serious situations and let him punt the ball because he could punt it a mile.”6 Michigan’s athletic director and former football coach, Fielding H. Yost, called Gedeon “the fastest man for his size in the country.”7

Not until his junior year in 1938 did Gedeon go out for the track team. According to one newspaper, “Michigan track coach Charles Hoyt is raving over hurdler Elmer Gedeon, a junior and Wolverine football player.” However, the report continued, “Elmer is more interested in winding up in pro baseball.”8

In February 1938, Gedeon ran his first hurdles race since high school, against rival Michigan State. He still enjoyed that winning touch. The star athlete set meet records in both the high and low 65-yard hurdles. In March, he tied an American record by running the 70-yard high hurdles in 8.6 seconds.9

Gedeon won two conference championships as a collegiate hurdler and took third place in the 120-yard hurdles at the 1938 NCAA championships. He also served as president of his fraternity, Phi Gamma Delta.10

Gedeon often trained with the Wolverines’ track team in the morning and practiced with the baseball squad in the afternoon. On April 13, 1938, he hit two home runs against the Virginia Military Institute. The local Ann Arbor newspaper said his first homer “was a mighty clout (hit) high up on a bank in deep left field.”11 He finished his junior season hitting .286 (28-for-98) and tying for the team lead with five home runs.12

How good could Gedeon have been had he devoted all his considerable athletic prowess to running the hurdles? Hoyt said, “I have no doubts that Elmer could have run under 14 seconds in the (120-yard) high hurdles if he were able to give it the necessary time and work.…With the Olympics coming up in 1940, he would be a cinch to make the trip for Uncle Sam.”13

Ultimately, of course, Gedeon chose baseball over track. He told a reporter in 1939, “I’m not sure I would have been chosen for the Olympic team next summer, but I heard I was being considered.”14 (The 1940 Olympic games, scheduled first for Tokyo, Japan, and then moved to Helsinki, Finland, were ultimately canceled because of World War II.)

As a senior in 1939, Gedeon batted .320 (32-for-100). He played one of his best games for the Wolverines against the University of Maryland on April 15. Gedeon had a triple and a homer to lead Michigan to a 6-0 victory.15 Apparently, a local Washington D.C. umpire named “Bottle” Cox was on hand for this game and recommended Gedeon to the Washington Senators.16

Gedeon signed with the Washington Senators on May 11, 1939, but asked the Senators not to disclose the contract until after June 1, so he could finish his collegiate career. The Senators complied, sending Gedeon’s contract to the league office on June 3, 1939.

Gedeon began his professional career with the Orlando (Florida) Senators of the Class D Florida State League. Some thought that Washington might be grooming Gedeon to take over for Jimmy Wasdell, a young veteran with little power. Gedeon said, “I don’t know what’s in store for me. If I make the grade, I’ll probably be kept.”17

In 67 minor-league games, Gedeon batted .253 and stole 15 bases. But on August 21, Commissioner Landis declared Gedeon a free agent because his May 11 contract was not submitted to the league office within 20 days, per league rules. The Senators were allowed to re-sign Gedeon upon promising not to violate the rule again.18

Possibly due in part to his loyalty in re-signing with the Senators, Gedeon was promoted to the big-league club in September 1939, and played his first game on September 18 against the Detroit Tigers. Manager Bucky Harris sent him into right field as a late-inning defensive replacement; Gedeon made a diving catch of a Charley Gehringer liner, and struck out in his lone at-bat.19

The following day, Gedeon batted sixth against the Cleveland Indians at Griffith Stadium. He recorded his first hit on a leadoff single in the second inning against left-hander Harry Eisenstat, but was forced at second by the next batter, Mickey Vernon. Gedeon batted again in the third inning and walked. This time he made it to second base but was left stranded.

Gedeon scored his lone big-league run in the fifth inning. He reached base via a bunt, again off Eisenstat, to load the bases with none out. Vernon followed with a two-run single that advanced Gedeon into scoring position and knocked out Eisenstat. Johnny Broaca entered the game in relief, but the first batter he faced, Al Evans, singled to bring home Gedeon and give the Senators a 7-4 lead. Early Wynn then bunted into a triple play to end the inning.

Floyd Stromme, Cleveland’s third pitcher that day, struck out Gedeon to start the seventh. Elmer singled against Joe Dobson in the eighth inning for his third hit of the day, but was left stranded again. In front of about 500 fans, the Senators won, 10-9, and improved to 63-81. A writer from the Associated Press complimented Gedeon for making “a beautiful running catch on his only chance in the outfield.”20

Pitchers held Gedeon hitless in his three other games, two against Cleveland and one versus the Yankees. In a five-game major-league career, he went 3-for-15 (.200) with three singles and a run scored. While Baseball Reference credits him with an RBI, his game logs do not indicate that he ever drove in a run. Gedeon walked twice and struck out five times.

Gedeon played in 1940 for the Charlotte (North Carolina) Hornets, the Senators’ affiliate in the Class B Piedmont League. He hit .271 and knocked 11 home runs in 131 games. Once again he ended the season in the majors, but never appeared in a game. Even so, Senators owner Clark Griffith said, “Gedeon is exceptionally fast for a big man [6-foot-4 and 196 pounds], and we considered him a fine prospect for a regular job with our club.”21

The Army summoned Gedeon for military service in January 1941. Although he started spring training with Charlotte, shortly thereafter he reported to Fort Thomas, Kentucky, and then to the Cavalry Replacement Center at Fort Riley, Kansas, where he was designated a corporal. That assignment puzzled the lifelong city resident. “The only horse I ever saw was the one the milkman used,” he said.22 Reno Simone, who also served at Fort Riley, said, “I was assigned to the kitchens, and one time Elmer showed up and said he was tired of his men being assigned kitchen detail, so he put himself on KP.” Later, “two officers showed up and gave Gedeon orders to get ready to play baseball. Elmer asked to borrow my tennis shoes as he had not brought his baseball spikes with him.”23

Gedeon joined the Army Air Corps in late May 1941. He earned his pilot’s wings and a commission as a second lieutenant while training at Williams Field in Arizona. In addition to his height and weight, Gedeon’s draft card also noted his light complexion, blond hair, and blue eyes.

On August 9, 1942, Gedeon was serving as the navigator aboard a B-25 that crashed into a North Carolina swamp shortly after takeoff. He suffered serious burns and three broken ribs but still managed to save one of his crewmates, who had a broken back and two broken legs. Two crew members died in the crash, and Gedeon spent three months recovering at a military hospital. He lost 50 pounds. “I got that weight back after I started to take vitamin pills,” Gedeon said. “They gave me four each meal. The ordinary dose is two a day. I never ate so much in my life.”24

The Army presented Gedeon with the Soldier’s Medal for heroism and bravery. According to the citation, “The heroism displayed by Lieutenant Gedeon on this occasion reflects great credit upon himself and the military service.”25 Ever the optimist, Gedeon said after his brush with death, “I had my accident. It’s going to be good flying from now on.”26

Ordered to Ardmore Army Airfield in Oklahoma, Gedeon learned to fly a twin-engine Martin B-26 Marauder, the so-called Widow Maker, an airplane infamous for its high accident rate on takeoffs and landings. According to one description, “It was a highly strung, unforgiving airplane that needed to be tamed by the most experienced pilots.”27

Before he boarded a passenger ship for England, Gedeon said, “I’ll be back in baseball after the war.” Not long afterward, in an article for the Associated Press, a reporter noted, “(Gedeon) hopes to pick up after the war where he left off.” Gedeon said, “It’s a matter of time. … If the war ends before I’m past the playing age, I’ll return to the game. If I’m too old, I’ll do something else.”28

Gedeon joined the 586th Bomber Squadron, a part of the 394th Bombardment Group and Ninth Air Force. According to the group’s historian, J. Guy Ziegler, he was “one of the most popular officers in the group.” On April 15, 1944, Gedeon turned 27 years old. Four days later, he flew his B-26 on a bombing run over a railyard in Belgium with “good to excellent results,” according to a report.29

On April 20, Gedeon and 29 other Marauder pilots took off from Boreham Airfield in England. Their target was a German V-1 cruise missile site under construction in Bois d’Esquerdes, France. Gedeon flew behind group leader Captain Darrell Lindsey at about 12,000 feet above the English Channel. The planes reached their target point at 7:30 p.m. Heavy anti-aircraft fire punctured the sky.

Gedeon’s plane dropped its ordinance just before taking a direct hit. The cockpit area burst into flames. Taaffe recalled, “We got caught in searchlights and took a direct hit under the cockpit. I watched Gedeon lean forward against the controls as the plane went into a nosedive and the cockpit filled with flames. He must have been thinking, ‘Oh, no, not again.’”30 Some crew members jumped from the plane, while others died as the Marauder crashed into the ground.31 Of the seven crewmen aboard, Taaffe was the lone survivor.32

The Army reported Gedeon as missing in action. In May 1945, Andrew Gedeon learned the fate of his son. Elmer had been buried at a British military cemetery in St. Pol, France. In June 1949, Elmer Gedeon’s remains were reinterred at Arlington National Cemetery, outside Washington, D.C.

More than 500 major-leaguers served in the military during World War II. Many played baseball games in front of servicemen as a morale booster. Some, including Bob Feller, Hank Greenberg, and Warren Spahn, saw action in battle. Harry O’Neill, who caught one game for the Philadelphia Athletics in 1939, died when a Japanese sniper shot him at Iwo Jima on March 6, 1945. Like Gedeon, he was 27 years old.

In 1983, the University of Michigan inducted Gedeon into its Hall of Honor. According to a citation, “Elmer Gedeon is best remembered for his courage and the life he sacrificed for his country during World War II.”33 In a tribute column from May 2022, Neal Rubin of the Detroit Free-Press wrote, “I wonder what height (Gedeon) might have reached had he decided to stay on the ground one afternoon in April 1944. Or maybe, in flying and dying, he came as close as he ever could to immortality.”34

Sources

The author drew upon several previous writeups of Elmer Gedeon’s life and career. Special credit goes to the work of:

Gary Bedingfield, who has chronicled the lives of players who died in military service on his website, Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice, and in his book, Baseball’s Dead of World War II (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2010).

Terry Frei, who has written about Gedeon over the years as a journalist for the Portland Oregonian and Denver Post, as well as his own website.

These accounts contained quotations from various primary sources. All efforts were made to find the details of these original reports for the Notes, but in some cases, the citations are incomplete.

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Rory Costello and Rick Zucker and fact-checked by Paul Proia.

Notes

1 Gary Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon,” Baseball’s Greatest Sacrifice, updated May 25, 2014. (https://www.baseballsgreatestsacrifice.com/biographies/gedeon_elmer.html). Original source: interview of James Taaffe conducted in November 1999 (hereafter Bedingfield-Taaffe interview).

2 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.”

3 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.”

4 Neal Rubin, “Remembering a Major Leaguer’s Last Bombing Run,” Detroit Free-Press, May 29, 2022: A4.

5 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.”

6 Rubin, “Remembering a Major Leaguer’s Last Bombing Run.”

7 George S. Alderton, “The Sport Grist,” Lansing (Michigan) State Journal, September 15, 1937: 16.

8 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.” Original source: wire service reports carried in various newspapers (e.g., Northwest Arkansas Times and Biloxi Daily Herald, January 31, 1938).

9 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.”

10 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.”

11 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.” Full details of original Ann Arbor News report from April 4, 1939, are presently unavailable but are noted in Baseball’s Dead of World War II.

12 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.”

13 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.” Original source: article by Dick Sierk for the Michigan Daily, May 7, 1939.

14 Terry Frei, “Elmer Gedeon, Michigan and Washington Senators,” TerryFrei.com, unknown date (http://www.terryfrei.com/gedeon.html). Original source: article by Howard Preston for the Cleveland News, unknown date, 1939.

15 Burton Hawkins, “Netmen Rout Richmond, but Nine is Blanked by Wolverines, 6-0,” the Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), April 16, 1939: E-3.

16 Burton Hawkins, “Gelbert’s Spirit, Punch Pushing Travis Out of Job With Nats; Appleton on Slippery Path,” the Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), June 3, 1939: 14

17 Frei, “Elmer Gedeon, Michigan and Washington Senators.” Original source: article for Cleveland Press (details unavailable).

18 “Gedeon’s Contract Voided by Landis,” Detroit Free-Press, August 22, 1939: 16.

19 “Wildness Aids Bengal Defeat,” Escanaba (Michigan) Daily Press, September 19, 1939: 10. Frei, “Elmer Gedeon, Michigan and Washington Senators.” See also Frei, “Remember Gedeon each Memorial Day,” Denver Post, May 30, 1999 (https://extras.denverpost.com/rock/frei0530.htm). Terry Frei wrote a column about Gedeon many years later for the Portland Oregonian. He noted that Gedeon’s name was listed in the box score as “Gedgeon.”

20 “Gedeon Does Well in Major League,” Escanaba (Michigan) Daily Press, September 20, 1939: 2.

21 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.” Details of original Associated Press wire reports presently unavailable.

22 Rubin, “Remembering a Major Leaguer’s Last Bombing Run.”

23 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.” Original source presently unavailable.

24 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.” Details of original Ann Arbor News report presently unavailable.

25 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.” Original source presently unavailable.

26 Rubin, “Remembering a Major Leaguer’s Last Bombing Run.”

27 “Martin B-26 Marauder,” The Aviation History Online Museum (http://www.aviation-history.com/martin/b26.html).

28 Marc Lancaster, “Elmer Gedeon, a big leaguer who sacrificed everything,” The Low Stone Wall, updated April 20, 2019 (https://lowstonewall.com/2019/04/20/elmer-gedeon-a-big-leaguer-who-sacrificed-everything). Originally written as a Memorial Day piece for The Washington Times in 2014. Original press source: “Gedeon Will Return to Baseball If War Doesn’t Last Too Long,” The Times Recorder (Zanesville, Ohio), February 10, 1943.

29 Lancaster, “Elmer Gedeon, a big leaguer who sacrificed everything.”

30 Bedingfield, “Elmer Gedeon.” Bedingfield-Taaffe interview.

31 Sam Clayton, “Elmer Gedeon, Cleveland’s WWII Hero And Top Athlete, Saluted Ohio’s Best Over Memorial Day Weekend,” Daily Cleveland News, May 29, 2022 ( https://dailyclevelandnews.com/elmer-gedeon-clevelands-wwii-hero-and-top-athlete-saluted-ohios-best-over-memorial-day-weekend/).

32 Lancaster, “Elmer Gedeon, a big leaguer who sacrificed everything.”

33 “Elmer Gedeon,” University of Michigan Hall of Honor (https://mgoblue.com/honors/university-of-michigan-hall-of-honor/elmer-gedeon/54).

34 Rubin, “Remembering a Major Leaguer’s Last Bombing Run.”

Full Name

Elmer John Gedeon

Born

April 15, 1917 at Cleveland, OH (USA)

Died

April 20, 1944 at St. Pol, (France)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.