Sherry Magee

Today we would call Sherry Magee a five-tool player: he could hit, run, field, throw, and hit with power. For more than a decade he was the Philadelphia Phillies’ clean-up hitter and greatest offensive star, setting the all-time team record in stolen bases (387) and ranking among the top ten in almost every other category. Magee’s defense was nearly the equal of his offense; sensational catches with his back to home plate were his trademark, and Pirates scout Frank Haller commented that his every throw was “on a line and right on target.” He was undoubtedly the National League’s most valuable player in 1910, and either he or Johnny Evers deserved the appellation in 1914. That season one Philadelphia writer called Magee “probably the best all-around ball player in the National League,” and a Cincinnati reporter went a step further: “To my mind Sherwood Magee is one of the best all-around players the game has ever seen.”

Today we would call Sherry Magee a five-tool player: he could hit, run, field, throw, and hit with power. For more than a decade he was the Philadelphia Phillies’ clean-up hitter and greatest offensive star, setting the all-time team record in stolen bases (387) and ranking among the top ten in almost every other category. Magee’s defense was nearly the equal of his offense; sensational catches with his back to home plate were his trademark, and Pirates scout Frank Haller commented that his every throw was “on a line and right on target.” He was undoubtedly the National League’s most valuable player in 1910, and either he or Johnny Evers deserved the appellation in 1914. That season one Philadelphia writer called Magee “probably the best all-around ball player in the National League,” and a Cincinnati reporter went a step further: “To my mind Sherwood Magee is one of the best all-around players the game has ever seen.”

The son of an oilfield worker, Sherwood Robert Magee was born on August 6, 1884, in Clarendon, Pennsylvania. “The Irish traits of quick wittedness, a hot temper and an aggressive love of fighting are his by birthright,” wrote John J. Ward in Baseball Magazine. Regarding Magee’s personality, one Philadelphia reporter called him “as gentle and good-natured as an old woman.” Ward, however, described him as “a man for whom it is easy to conceive a great liking or a passionate hatred.” Though he stood only 5’11” and weighed 179 lbs., he was physically imposing—”husky” and “burly” were adjectives commonly used to describe him. In addition to his baseball skills, Sherry was a crackerjack bowler and a standout football and basketball player.

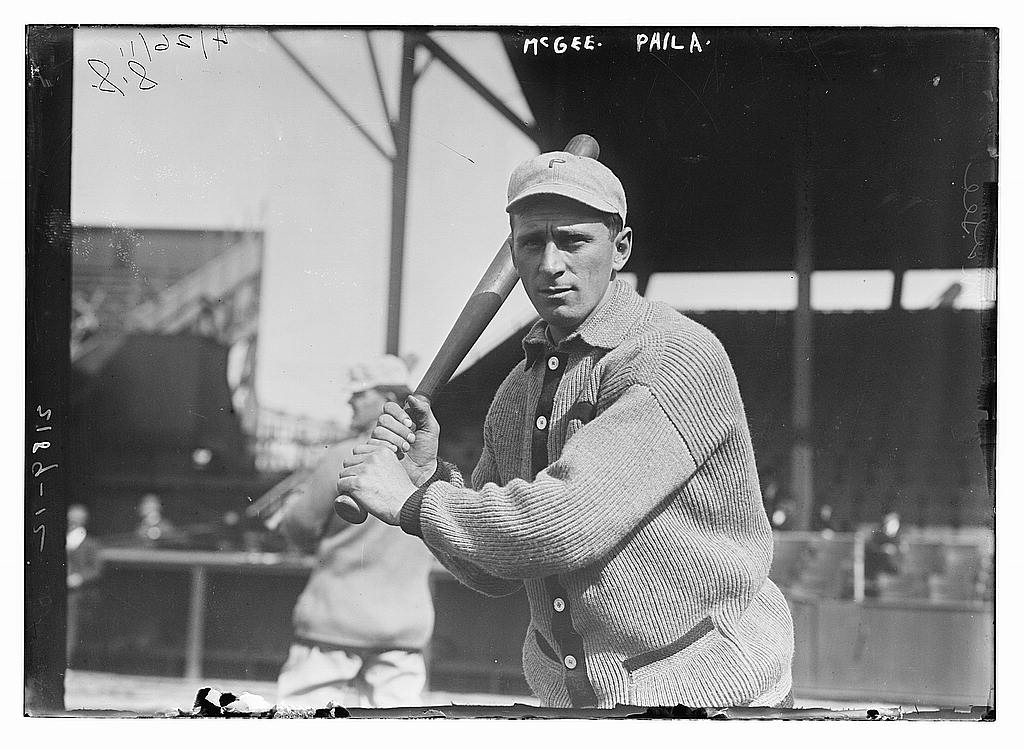

In late-June 1904, Phillies scout Jim Randall was getting off a train in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, when he overheard some baseball fans raving about a kid named Magee who played left field for the local Lindner team, which one reporter described as “a sort of scrub aggregation.” After checking out the kid and liking what he saw, Randall approached him and asked if he’d be interested in playing with a league team. “With what team?” asked Magee. “With the Phillies,” replied Randall. Sherry couldn’t believe that he’d heard right, and it wasn’t until Randall pulled out a contract and offered him a roll of bills that he realized he wasn’t dreaming. The next day he was in Philadelphia, practicing with the Phillies, and the day after that—June 29, 1904, to be exact—19-year-old Sherry Magee (listed as “McGee” in the box score) was starting in left field against the Brooklyn Superbas.

Philadelphia’s strength in 1904 was its outfield—Shad Barry in left, Roy Thomas in center, and John Titus in right—but an injury to Titus caused Barry to fill his position, opening up left field for Magee. Though the nervous rookie misjudged two fly balls, both of which led to Superba runs in an 8-6 loss, he did hit the ball hard in each of his four at-bats. “Magee overcame his unfamiliarity with the Philadelphia grounds and soon learned to field as became a big leaguer,” wrote Ward. Three weeks later, when Titus was able to return to the lineup, Sherry was so firmly entrenched in left field that the Phillies traded Barry to Chicago. Magee batted .277 for the season and led the team with 12 triples despite playing in just 95 games. Sportswriters considered his jump from the sandlots to immediate stardom in the major leagues to be without precedent.

Over the next several years Sherry Magee rarely missed a game, establishing himself as one of baseball’s young stars. In 1905, his first full season, he was the biggest factor in Philadelphia’s gain of 31 victories over 1904, scoring an even 100 runs, stealing 48 bases, and batting .299 with 24 doubles, 17 triples, and five homers. The next year he was just as good, hitting .282 with 36 doubles, eight triples, and six homers and finishing second in the NL in stolen bases with 55, a modern Phillies record that stood until Juan Samuel swiped 72 in 1984. In 1907 Magee had his best season yet, leading the NL with 85 RBIs and placing second to perennial batting champion Honus Wagner with a .328 average.

But as he reached stardom, Sherry also developed a reputation as a troublemaker. “On the ball field Magee is so fussy most of the time that people who do not know him naturally form the opinion from his actions that he is a born grouch,” wrote the Philadelphia Times after the 1908 season. “That he is one of the most hot-headed players in either big league is admitted; it couldn’t be denied, because the records, showing how often he has been suspended for scrapping with the umpires, speak for themselves.” Off the field, the young slugger could be just as difficult. The captain of the Phillies during Magee’s early years was Kid Gleason, who kept an old leather belt in his locker that he used on young players who misbehaved, and on several occasions Magee literally felt the captain’s wrath. Sherry also became known for “crabbing” at teammates. “Magee, like Evers, has an unusual amount of base ball gray matter and spirit,” explained one reporter. “This spirit plays for victories and is easily upset when ‘bones’ are pulled.”

In 1909 Magee slumped to .270 (still 26 points above the league average) and played with “marked indifference,” prompting rumors that he would be traded to the New York Giants for holdout slugger Mike Donlin. The Phils refused the deal because of the age difference between the two players (Donlin was six years older), and their patience was rewarded when Magee put together his finest season in 1910. Playing in all 154 games, he broke Wagner’s tenure on the batting throne by hitting .331, and also led the NL with career highs in runs (110), RBIs (123), and on-base percentage (.445). He walloped 39 doubles, 17 triples, and six homers to give him a league-leading .507 slugging percentage, and his 49 stolen bases ranked fourth in the NL.

Sherry was enjoying another banner year in 1911, but his season—and career—were marred by his actions in the third inning of a game in St. Louis on July 10. With the Phils leading, 2-1, Magee came to bat with one out and Dode Paskert on second and Hans Lobert on first. With two strikes, rookie umpire Bill Finneran called Magee out on what appeared to be a high pitch, prompting Magee to turn away in disgust and throw his bat high in the air. Finneran yanked off his mask and threw him out of the game. Sherry, who had been heading to the bench, suddenly turned and attacked the umpire, clutching him for a second before hitting him with a quick left just above the jaw. With blood spurting from his face, Finneran fell to the ground on his back, apparently unconscious.

The field umpire, Cy Rigler, and the Phillies manager, Red Dooin, who was coaching first base, both rushed to the plate to assist Finneran; meanwhile Paskert and Lobert ran all the way around the bases, erroneously thinking that time had not been called, and Magee stood in front of the Phillies bench for a few seconds before several teammates led him under the stands. When he came to and realized what had happened, Finneran ripped off his chest protector and tried to reach the Philadelphia bench. Rigler tried to hold him back but only partly succeeded, his shirt becoming blood-covered in the process. Kitty Bransfield eventually intercepted Finneran and prevented him from reaching the bench. After he calmed down, Finneran went to the hospital for treatment of what was thought to be a broken nose. The game continued with Rigler behind the plate, and the Phillies won, 4-2, after which Magee expressed regret for the incident, offering as an excuse that Finneran had called him a vile name. Dooin added that the rookie umpire had been too aggressive all season, often bragging about his ability as a fighter and threatening to lick players, including Dooin himself during a late-June series in Boston.

Unsympathetic to the Phillies’ pleas, NL President Thomas Lynch, himself a former umpire, announced that Magee had been fined $200 and suspended for the balance of the season—the most drastic punishment meted out since 1877 when four players were barred for dishonesty. The Phillies appealed to the NL board of directors, arguing that Lynch had been too severe, especially since one regular outfielder, Titus, already was out with an injury and the club was fighting for its first pennant. The directors declined to overturn the suspension, and the Phillies went 13-16 while Magee was out of action, tumbling to fourth place, 6.5 games behind the Cubs. At that point Lynch reinstated him, but even though Magee hit seven of his 15 home runs after his return, the Quakers climbed no higher in the standings by season’s end.

In the following year’s city series against the Athletics, Magee was hit by a pitch during batting practice and broke his right wrist and forearm, putting him out for the first month of the season. He was scarcely back when he went out again following an outfield collision with Paskert. Overcoming his injuries to bat .306 in both 1912 and 1913, Sherry combined with Gavvy Cravath to give the Phillies what Ward called “the greatest ‘team’ of extra-base specialists in existence.” But despite all he had accomplished in his decade with the Phillies, Magee remained unpopular with the infamous fans of the City of Brotherly Love. “For five years, prior to 1914, the local fans have roasted Sherwood Magee,” wrote a Philadelphia reporter. “They cheered his long swats as all fans do, but still they shouted for his release.” Ward agreed, attributing Magee’s lack of popularity to the generally-held belief that he was “a man who played for his own personal record and not for the good of the team.”

That all changed, however, when Magee was named captain of the Phillies in 1914. “When he was given the captaincy everyone looked at affairs from a different viewpoint,” said one veteran teammate. “Now he could talk all he liked and there would be no resentment, for that was all a part of his job. And it gave the added stimulus to Magee that made him the greatest teamworker we had.” After opening the season at his usual position in left field, Sherry demanded an opportunity to play shortstop in mid-May when it became apparent that none of the players attempting to replace the departed Mickey Doolan was adequate. “I can’t do any worse than some of the men that have been in there,” he told Dooin. Before the Phils acquired Jack Martin in July, Magee played 39 games at Doolan’s old spot, performing surprisingly well for a career outfielder. With characteristic immodesty, he even declared himself among the best shortstops in the business. “Others were more conservative in their estimate of his ability,” wrote one reporter, who nonetheless acknowledged that he was not the worst of Doolan’s replacements.

Due to injuries to other players, Magee also played a significant number of games at second base, center field, and first base in 1914. “In spite of the constant shifting of position on a hopelessly demoralized team, he proved himself the most valuable batsman in the league,” wrote Ward. Magee batted .314 (third in the NL) and led the league in hits (171), doubles (39), RBIs (103), and slugging percentage (.509). After that kind of season, he was shocked when the Phillies passed him over and appointed Pat Moran as manager to succeed Doolin. Magee negotiated half-heartedly with the Federal League’s Baltimore Terrapins, whose players included Doolan and several other former Phillies, but what he really wanted was to be traded to a winning team. “This great ball player has been hitched to losing teams for so long that with each season the desire to be with a champion has grown stronger,” wrote one reporter.

On December 26, 1914, Magee received a belated Christmas present when the Phillies dealt him to the world-champion Boston Braves for cash and two players to be named later. The trade had its critics in both cities. Braves manager George Stallings, who already had one crab on his hands with Evers, now had to contend with a second one in Magee. He became further dismayed when one of the Boston players in the deal turned out to be Possum Whitted, a hustling center fielder who had been one of his favorites. And in Philadelphia, one reporter wrote, “Just when Magee becomes popular with the fans, and is playing the game of his life, the club makes another mistake by permitting him to go to a rival club.” But some Philadelphians had long believed that Magee was the “jinx” that had been following the Phillies, and they were happy to see him go. What happened to Sherry in 1915—when the Phillies won their first-ever pennant—would lend evidence to their suspicions.

Reporting to spring training in Macon, Georgia, Magee was in a Braves uniform no more than 15 minutes when he stepped in a hole while shagging a flyball. He fell and injured his shoulder. Weeks later, when it failed to improve, he finally saw a doctor and learned that his collarbone was broken. Magee was only 30 years old but never again was the same player. He had batted over .300 three years in succession and had hit 15 homers in 1914, but in 1915 he batted just .280 with only two homers. Sherry was worse the following year, batting a meager .241. In 1917 he again performed poorly for Boston—in 72 games he batted .256 with only one homer—but turned around his career when the Cincinnati Reds picked him up on waivers in August. Filling in for the injured Greasy Neale, Magee batted .321 over the rest of the season. His revitalization continued during the war-shortened 1918 season when he batted .298 and drove in an NL-leading 76 runs, becoming the only non-Hall of Famer to lead the league in RBIs four times.

The next season a serious illness forced Magee out of action for two months, causing him to lose his regular position to rookie Pat Duncan. Though he batted a career-low .215, Sherry realized his long-held ambition of playing for a pennant-winning team. Appearing twice as a pinch hitter in the 1919 World Series, he picked up one hit and was released after Cincinnati’s victory, marking the end of his 16-year career as a major league player.

Though he had skipped the minors on his way up, Magee played seven years in the bushes on his way down, six of them in the American Association. His best full season came with Minneapolis in 1922 when he batted .358, third-best in the AA, and set a record that August by reaching base in 20 consecutive pinch-hitting appearances. Three years later Magee got off to an even better start, leading the AA with a .464 average, but Milwaukee released him in June after losing 16 of 18 games. In desperation he begged for work from his last major league employer, Reds owner Garry Herrmann. His letter remains on file at the National Baseball Library:

I think I could be of some use to your club as the fans were always for me there and maybe I could improve the hitting of some of the players. I have turned out some one every year for [Milwaukee owner Otto] Borchert. . . . My Wife was sick all Winter so I am about down. [Former Milwaukee teammate Chuck] Dressen [then playing for the Reds] can tell you about my ability with that bat. Maybe I can help pep up your club on the coaching lines also. You know I never drank Whiskey and don’t to-day and have a lot more sense than I had there before.

But when no job from Herrmann was forthcoming, Magee signed on as player-coach with Jack Dunn‘s Baltimore Orioles. He held on for one more season, finally retiring as an active player at the age of 42.

Unlike many players of his era, Sherry had no trade to fall back on; for years he had spent the winter with his in-laws in Fulton, New York, “living a life of ease and pleasure from the close of one season to the opening of another.” He was ill-prepared for what to do with the next phase of his life, but an inspiration had come to him while presiding over exhibition games at the Orioles’ 1926 training camp: he would become an umpire.

In 1927 Magee served as an arbiter in the New York-Penn League. His work attracted so much positive comment that he was named to the NL staff for the coming season by John Heydler, who had been an assistant to President Lynch at the time of the Finneran incident in 1911. Picking up on the irony of umpire-baiter turned umpire, many veteran reporters expected Magee to be a disaster. “His appointment at the time brought a reflective smile to the fans and players that recalled his ancient feuds with the umpires,” wrote one scribe after the 1928 season, “but Sherry surprised the old-timers by his cool decisions on the field, the manner in which he ran his ball games and the cleverness of his work.” Heydler commented that Magee had made good in his first year and was destined to become one of the game’s leading umpires.

Sherry spent the 1928-29 offseason at his Philadelphia home at 1152 North 65th Street, working in a nearby restaurant. In early-March he came home complaining of a headache and fever. A physician diagnosed that he was suffering from pneumonia, and his condition worsened over the ensuing week. At the age of 44, Sherry Magee died at 8:45 p.m. on March 13, 1929, with his wife, Eda, and three grown children at his bedside. He is buried in the Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill. The obituary that went out over the AP wire described Magee as “one of baseball’s most colorful figures,” “one of the greatest natural batsmen in the game,” and “a master in judging fly balls, a fine base runner and full of so-called ‘inside baseball.’”

Note: An earlier version of this biography appeared in Tom Simon, ed., Deadball Stars of the National League (Washington, D.C.: Brassey’s, Inc., 2004).

Sources

In preparing this biography, the author relied on Sherry Magee’s file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York. In addition, the author also relied on his own “Sherry Magee, Psychopathic Slugger,” from the Baseball Research Journal (SABR 2001).

Full Name

Sherwood Robert Magee

Born

August 6, 1884 at Clarendon, PA (USA)

Died

March 13, 1929 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.