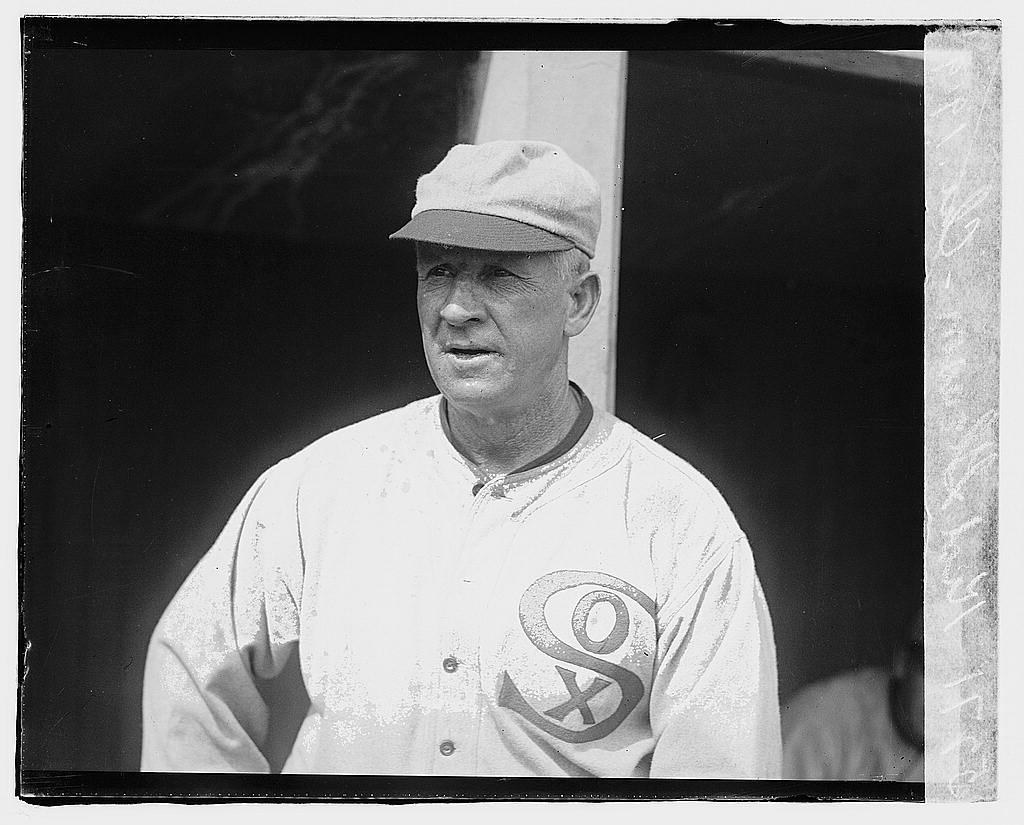

Kid Gleason

He is remembered as the manager of the most infamous baseball team ever, but less well known as a versatile and gutsy ballplayer of the 19th century. His counseling and humor became crucial to the success of many big leaguers in the years between the World Wars. He was the Kid from the coal country who rose above his humble beginnings to become a much-loved figure in the national pastime.

He is remembered as the manager of the most infamous baseball team ever, but less well known as a versatile and gutsy ballplayer of the 19th century. His counseling and humor became crucial to the success of many big leaguers in the years between the World Wars. He was the Kid from the coal country who rose above his humble beginnings to become a much-loved figure in the national pastime.

William J. Gleason was born on October 26, 1866, in Camden, New Jersey, across the river from Philadelphia. His family moved to the coal regions of Pennsylvania’s Pocono Mountains, and Gleason grew up in the hard life of a “coalcracker” family. As with many boys of the era, he played games with his five brothers and one sister. His recreational interests turned to baseball; indeed, younger brother Harry played five years at third base in the American League with Boston and St. Louis. Gleason skipped college to become a professional ballplayer, displaying both a potent bat and strong pitching arm (he batted and threw right-handed). He was not a large man, growing to 5-feet-7 and weighing just under 160 pounds as an adult, and was therefore labeled with the everlasting nickname “Kid.”

Gleason played two seasons in the minor leagues of northern Pennsylvania. In 1886 at Williamsport of the Pennsylvania State Association, he batted .355 and stole 20 bases in 36 games.1 In 1887, again at Williamsport, he posted a 9-11 record with a glittering 1.97 earned-run average as a pitcher, and batted .348 as a change player – today known as a utility player – at both second base and the outfield. His obvious talent landed him a spot with the nearby Scranton team of the International League, then as now a top minor league. Though his pitching record was abysmal (1-12, 3.67 ERA), his all-around talents shone through as he batted .313 as an outfielder when not pitching.

Harry Wright, manager of the Philadelphia National League entry (then known as the Quakers, but later as the Phillies), heard about the prowess of young Gleason and invited him to try out with the team in the spring of 1888. He made the team largely on the basis of his performance in a March 31 exhibition game against the University of Pennsylvania varsity, when he struck out 12 batters and yielded no earned runs.

From the day of Gleason’s major-league debut on April 20, his 1888 season was largely limited to the pitcher’s mound, even though Philadelphia’s batting lineup that season was relatively anemic. Gleason started 23 games for the Phillies in his inaugural season, winning seven, though his 2.84 ERA closely tracked with the league average. His follow-up season in 1889 was significantly less successful as his ERA ballooned to over five runs per game.

As 1890 arrived, the rival Players League was formed and Gleason had the opportunity to jump the team. Instead he displayed a rather unusual (for his time) level of loyalty for his manager and decided to stay with the Phillies, saying, “Harry Wright gave me my chance two years ago when I was just a fresh kid playing coal towns, and I’m not running out on him now.”2 As a result, Gleason was one of several prominent players expelled from the Brotherhood of Base Ball Players for refusing to jump to the new Players League.

The outcome of his decision was a coming of age for Gleason’s pitching abilities. His 38 victories and .691 winning percentage ranked second in the National League for 1890. Gleason displayed workhorse abilities by hurling 506 innings and completing 54 games (all but one of his starts), both ranking third in the league. His follow-up season of 1891, significantly more challenging after the absorption of Players League returnees, still produced 24 victories, tops on the team.

Gleason was sold to St. Louis before the 1892 season and assumed a position in the starting rotation for the next two seasons, winning 20 or more games both seasons while playing more games as a spare fielder. He started 45 games each season, completing all but two in 1892 while hurling 400 innings (he added 380? in 1893). Though not among the league leaders, he nonetheless made solid contributions.

It should not be surprising that Gleason, like any spirited St. Louis player of the day, ran afoul of team owner Chris Von der Ahe. One day, the owner imposed a fine on Gleason by withholding $100 from his pay envelope. Kid marched into Von der Ahe’s office and yelled, “Look here, you big, fat Dutch slob. If you don’t open that safe and get me the $100 you fined me, I’m going to knock your block off.” Gleason got his refund immediately.3

Gleason got off to a poor start in 1894, losing six out of eight starts, and was sold to Baltimore for $2,400 in late June. According to David Ball’s research, Gleason did not report until July 17 because of a money dispute resulting from either back pay or a desire to obtain a share of the sale price (a common practice of the day).4 Once he arrived in Baltimore and received the tutelage of Ned Hanlon, Gleason rebounded with another successful season, winning 15 out of 20 starts and averaging only 2.3 walks per game, third best in the league. His contribution helped lead Baltimore to a pennant, something Gleason had yet to encounter in his career. More importantly, however, Gleason’s batting skills increased dramatically, as he averaged .349 in 86 at-bats.

Hanlon noted this quality as the 1895 season dawned. Due to strong pitching and uncertainty in his infield, Hanlon decided to remove Gleason from the mound after only five starts and position him at second base. Gleason earned some $2,000 for the season, among the best salaries in the league.5 Gleason responded with a .309 average, though his fielding percentage was below .900, abysmal even in those days. Despite winning another pennant, Hanlon decided that he could develop a better defense with a healthy John McGraw at third base and Henry Reitz back at second. He traded Gleason in the offseason to the New York Giants in exchange for slugging first baseman Jack Doyle.

Gleason closed his pitching career with 138 victories, a lifetime winning record, and a 3.79 ERA. In a 1931 interview with the Philadelphia Inquirer, Gleason reflected on his demise as a pitcher: “When I won 38 games for the Phillies (1890) I pitched every other day – had to, we had only 15 men. The reason the hurlers can’t work so often now is because of the increased pitching distance.”6

His pitching days behind him, Gleason settled into second base in New York over the next five years. He developed into one of the better second basemen of the time, leading the league twice in assists and once in putouts. His batting peaked at .317 with 106 RBIs in 1897 before a steady decline, though not enough to get him out of the lineup.

Gleason also served as team captain, and was credited by Baseball Magazine with inventing that most curious of baseball stratagems, the intentional walk.7 In a high-scoring contest against Chicago, the bases loaded with Colts in the eighth inning with two outs, and the Giants nursing a fragile 9-6 lead, Gleason strolled to the mound and proceeded to confer with pitcher Jouett Meekin and catcher Parke Wilson. Coming up to bat was Jimmy Ryan, one of the most feared Colts, but Gleason noted that the less intimidating hitter George Decker was on deck. All players returned to their position, and Meekin proceeded to toss four pitches wide of the plate. Ryan dutifully, though somewhat astonished, took his free pass and a run was forced in. Meekin then proceeded to fan Decker, and the Giants went on to win the game.

Gleason reached heroic status in New York City, though not only for his on-field abilities. He was going to the Polo Grounds on April 26, 1900, with teammates George Davis and Mike Grady when the ballplayers noticed smoke from an apartment house. Rushing to the scene, Davis climbed a fireman’s ladder to rescue a fainted woman, then Gleason joined him to lead another woman and a child down the fire escape. The fire left 45 families homeless but alive, thanks to the quick thinking of the Giants players.8

Baseball players have long been accused of gullibility, and Gleason was no exception. Upon completion of the 1900 season, a number of players assembled to play a series of exhibition games in Cuba. Some unnamed prankster convinced Gleason and Pirates outfielder Tom O’Brien that drinking an excessive amount of seawater would ultimately cure seasickness, though with some immediate illness. Both men fell for the trick and became violently ill. Gleason recovered, but O’Brien suffered internal damage and, tragically, later died from the prank.9

Gleason was a hard worker and believed in preseason conditioning long before the popularity of spring training. Residing in Trenton, upriver from Philadelphia on the New Jersey side, he paid a daily visit to the gymnasium and worked out for a few hours each day. The results became more critical as he was now in his mid-30s, past his physical prime.

The temptation of a rival league arose again with the advent of the American League raids in 1901. This time however, Gleason owed no allegiance to his manager and signed on with the new Detroit franchise, which featured two Kids up the middle – Gleason at second base and Elberfeld at shortstop. Gleason’s next two years in Detroit saw continued success in the field with significant putouts and assists, though he committed more errors both seasons than the rest of the league’s second basemen.

When peace arrived between the warring leagues in time for the 1903 season, Gleason was part of the interleague player-swapping, reuniting with the Phillies. For the next four seasons, he held forth at second base, leading the league in putouts at that position in 1905. His batting also showed a resurgence in both 1904 and 1905 while back in his adopted home town; he paced the 1904 team in games played, at-bats, hits, and total bases. In 1905 he tied for the team lead in games played and was the leader in at-bats.

During the 1906 season, Gleason’s everyday playing skills were diminishing, but not his spirit. On June 20 he spiked Pittsburgh’s Honus Wagner, who had just drilled a hit deep into the outfield, causing Wagner to stop at third base with a painful limp and miss three games. By 1907, at the age of 40, Gleason had become a utility player. Two brief but hitless appearances in 1908 completed his major-league playing career (other than one brief appearance at second base four years later). He ended his nearly 2,000-game career with more than 1,000 runs, averaging about a hit per game, accumulating a .261 batting average, 329 stolen bases, and 501 bases on balls.

Gleason spent two seasons out of baseball in 1910 and ’11 before returning to the major leagues as a coach in 1912, when former teammate Jimmy Callahan became manager of the Chicago White Sox.10 Gleason reflected on his career and style of play in the Philadelphia Inquirer: “They can’t bring back the old kind of game, not the way we played it. … I’d let them slide onto the bag, then kick them off the bag. That’s the way we put them out.” As for playing off the pitching mound, “Any time a man tried to steal I’d run over in front of him and slow him up.”11

Gleason made one final appearance in 1912, playing a game at second base and obtaining his last major-league hit despite his advanced age of 45. But his prime contribution to the White Sox was as team sparkplug. The Kid’s favorite trick was to sneak into Eddie Collins’s room during road trips and tie him to the bed with a razor strop.

Cleveland hurler Cy Falkenberg once told Baseball Magazine of his ability to stymie Gleason with his emery ball: “ ‘Kid’ Gleason used to watch me like a hawk, whenever I pitched against the White Sox. He would say to me, ‘I know you are doing something to that ball. You must be doing something to get it to break in that way.’ And then he would pick up the ball I had used and examine it carefully. But he could never detect the slight and almost invisible roughening of a small spot on the side. He kept at me continually, but I would jolly him along and he never got on to the secret.”12

Promoted to manager before the 1919 season, Gleason led the White Sox to the pennant with a record of 88-52. The White Sox led the league in runs scored, batting average, and stolen bases, showing the same spark at bat and in the field that Gleason had shown in his playing career. He called them the “best baseball team in the world,” a club he claimed had no weaknesses.13

One longstanding mystery of Gleason’s team in 1919 is why he held out his star pitcher, Eddie Cicotte, at the end of the regular season. Although the pennant race was locked up, Cicotte was the only major-league pitcher that season with a fair chance to win 30 games, a mark of pitching mastery in the 20th century. Yet he started only three games after September 5; he won his 29th game on September 19 and failed to win his 30th five days later. Speculation has long circulated that team owner Charles Comiskey refused to pay Cicotte a bonus that he would have earned had he won 30 games, so he is accused of ordering Gleason not to pitch Cicotte until the World Series.

The trouble with this theory is its lack of verification by the principals involved. Neither Cicotte nor Gleason ever raised the issue in any interview. Lowell D. Blaisdell has an excellent analysis of this dilemma, reaching a different conclusion.14 He notes that Gleason faced some serious concerns over the Series. First, pitcher Red Faber developed a sore arm and was inactive for the Series. Gleason now had only two reliable starters, Cicotte and Claude Williams, and the untested potential of Dickey Kerr. Moreover, the Series that year had the trial idea of a best-of-nine series, requiring the winner to post five victories before clinching the Series. Finally, the close proximity of the competing cities (Chicago and Cincinnati) led the leagues to decide on nine consecutive days of play, without travel days. How could Gleason hope to win such a Series with only two proven starters? His only chance was to alternate Cicotte and Williams on only two days’ rest, at most. Therefore, it seems plausible that Gleason merely held Cicotte out of the regular season to save him for the Series. This theory is bolstered by the New York Times report of September 21, 1919: “Gleason is not worrying much about his individual record. He is looking ahead and is loathe (sic) to take any chances with his star.” The news account added that Gleason “is figuring on using his star in three games of the series …”

History records the deeds of that team during the World Series, earning the sobriquet of Black Sox. When the gambling story finally broke the next year and came to trial, Gleason was the first witness for the defense, challenging an alleged meeting between players and gamblers at the very time they were holding a team practice in Chicago. Not only was Gleason not involved in the gambling, but he probably knew from the first game what was happening (prominent journalists Ring Lardner and Hugh Fullerton held similar suspicions). Author Gene Carney found some evidence that Gleason confronted his team about the fix during the World Series, but his efforts didn’t stop the White Sox from losing to the Reds in eight games. Gleason told a reporter afterward, “Something was wrong. I didn’t like the betting odds. I wish no one had ever bet a dollar on the team.”15

Though Gleason was found to be uninvolved in the scandal, he was personally affected by it for the rest of his life. His team finished a close second the following season, 1920, but failed to post a winning record in the three remaining years of his tenure. He ended his managerial career in 1923 with a record of 392-364.

Gleason returned to live in retirement in Philadelphia, but after two years the baseball bug bit him again. Now, it was Athletics manager Connie Mack who invited him to return to the coaching ranks. Gleason played a pivotal role in building an obscure franchise into a three-time world championship team through his clubhouse antics and seasoned advice. Gleason became known as the unofficial greeter at spring training with his winning smile and iron-tight handshake.

Gleason retired for the last time after the 1931 season, at the height of the Athletics’ success. He suffered from a heart ailment and became bedridden about the time of the 1932 World Series, the first one in four years without his beloved A’s. As Connie Mack was dismantling his team of stars, Gleason himself began slipping away from the scene. Living in the Philadelphia home of his daughter, Mamie Robb, Gleason died on January 2, 1933. Though his wife had died five years earlier, all of his siblings were still alive at the time, according to the New York Times obituary.

Gleason’s funeral reflected his popularity. The Philadelphia Inquirer estimated that more than 5,000 people attended, including longtime Giants manager and former teammate John McGraw; Mack; and Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis. To accommodate the crowd that could never fit into the funeral parlor, amplifiers were set up on the sidewalk for people to hear the service. Gleason was then buried in Northwood Cemetery in north Philadelphia.

Kid Gleason was much beloved by the baseball community. Upon hearing of his death, McGraw was quoted by the Philadelphia Inquirer as saying: “He was, without doubt, the gamest and most spirited ball player I ever saw and that doesn’t except Ty Cobb. He was a great influence for good on any ball club, making up for his lack of stature, by his spirit and fight. He could lick his weight in wildcats and would prove it at the drop of a hat.”16 McGraw was right: The spirit and guidance of the Kid from the coal fields was felt by his contemporaries and his players for years to come.

A version of this biography appears in “Scandal on the South Side: The 1919 Chicago White Sox” (SABR, 2015). Click here for more information or to order the book.

Sources

Ball, David, “Nineteenth Century Transactions Register,” version 2 (Cincinnati: David Ball, 2003).

Blaisdell, Lowell D, “Legends as an Expression of Baseball Memory,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 19, No. 3, 1992, 227-43.

Erardi, John, “A Series That Will Live in Infamy,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 12, 1997.

Kelleher, Garrett J., “More Than a Kid: The Story of Kid Gleason.” Baseball Research Journal, No. 17 (Kansas City, Missouri: Society for American Baseball Research, 1988).

Kofoed, J.C., “A Twenty-Five Year Record,” Baseball Magazine, April 1916.

Lane, F.C., “The Emery Ball: Strangest of Freak Deliveries.” Baseball Magazine, July 1915.

Linder, Douglas, “The Black Sox Trial: An Account,” accessed online at http://law.umkc.edu/faculty/projects/ftrials/blacksox/blacksoxaccount.html.

Lindner, Dan, “William J. Gleason (Kid),” in Ivor-Campbell, Frederick; Tiemann, Robert L.; and Rucker, Mark, eds. Baseball’s First Stars (Cleveland: Society for American Baseball Research, 1996).

New York Times

Philadelphia Inquirer

Thorn, John, and Pete Palmer, eds. Total Baseball (New York City: Warner Books, Inc., 2002).

Notes

1 J.C. Kofoed, “A Twenty-Five Year Record,” Baseball Magazine, April 1916.

2 Philadelphia Inquirer, March 16, 1890.

3 Kofoed.

4 David Ball. “Nineteenth Century Transactions Register,” version 2 (Cincinnati: David Ball, 2003).

5 Garrett J. Kelleher, “More Than a Kid: The Story of Kid Gleason.” Baseball Research Journal, No. 17 (Kansas City, Missouri: Society for American Baseball Research, 1988).

6 Ibid.

7 Kofoed. Subsequent research by author Peter Morris has shown that the intentional walk goes back at least to the 1870s.

8 Chicago Tribune, April 27, 1900.

9 New Castle (Pennsylvania) News, February 13, 1901.

10 Kid Gleason contract card, The Sporting News Baseball Player Contract Card Collection, LA84.org. His card says he ran a business in Philadelphia in 1910 and a “hand book” in New York City in 1911.

11 Kelleher.

12 F.C. Lane, “The Emery Ball: Strangest of Freak Deliveries.” Baseball Magazine, July 1915.

13 Washington Post, September 28, 1919.

14 Lowell D. Blaisdell, “Legends as an Expression of Baseball Memory,” Journal of Sport History, Vol. 19, No. 3, 1992, 227-43.

15 Chicago Tribune, October 10, 1919. More analysis of Gleason’s efforts can be found in Gene Carney, Burying the Black Sox: How Baseball’s Cover-Up of the 1919 World Series Fix Almost Succeeded (Washington, DC: Potomac Books, 2006), 46-47.

16 Kelleher.

Full Name

William J. Gleason

Born

October 26, 1866 at Camden, NJ (USA)

Died

January 2, 1933 at Philadelphia, PA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.