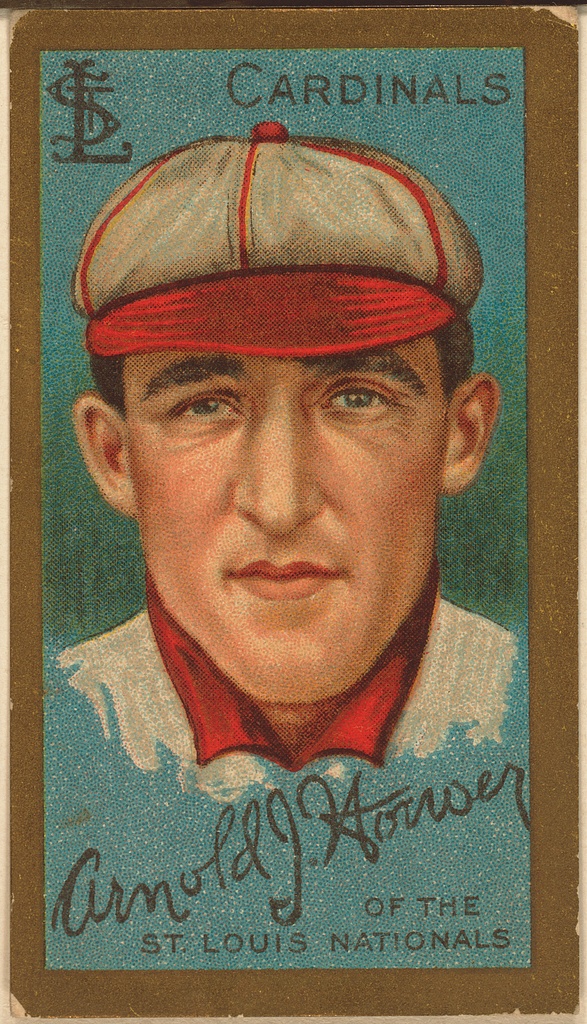

Arnold Hauser

“No more pitiful case exists in the annals of base ball than that of Arnold Hauser,” stated The Sporting News on April 9, 1914.1 Hauser, since debuting with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1910, had emerged as one of the game’s finest young shortstops. By 1913, however, injuries and personal tragedy began to derail both his career and his well-being. Hauser eventually spent most of his post-baseball life in a mental hospital. His troubles made for one of the most sensational baseball stories of the mid-1910s.

“No more pitiful case exists in the annals of base ball than that of Arnold Hauser,” stated The Sporting News on April 9, 1914.1 Hauser, since debuting with the St. Louis Cardinals in 1910, had emerged as one of the game’s finest young shortstops. By 1913, however, injuries and personal tragedy began to derail both his career and his well-being. Hauser eventually spent most of his post-baseball life in a mental hospital. His troubles made for one of the most sensational baseball stories of the mid-1910s.

Arnold George Hauser Jr. was born in Chicago on September 25, 1888. He was the fourth of Arnold and Mary Hauser’s six children. Arnold Sr. worked as a baker, and the large German American family lived in the city’s South Side. Arnold Jr. worked as a newsboy as a youngster, reportedly selling papers to Charles Comiskey. After the eighth grade, the boy left school. Shortly thereafter, in 1904, his father passed away.

As a teenager, Arnold Hauser apprenticed on Chicago’s sandlots. He seems to have spent a few seasons playing semipro ball, splitting 1908 between teams in Chicago and Lancaster, Wisconsin. Hauser made his professional debut with the Dubuque Dubs of the Illinois-Indiana-Iowa (or ‘Three-I’) League in 1909. Already earning a reputation as a dynamic fielder, Hauser contributed a .279 batting average as well. Famed scout Dick Kinsella, who also owned the Three-I’s Springfield Senators, recommended Hauser to St. Louis player-manager Roger Bresnahan, and the Cardinals drafted the youngster following the 1909 season.2

The Cardinals had averaged 100 losses over the five previous seasons, but a relative bright spot in 1909 was shortstop Rudy Hulswitt, “the cement of the Cardinals’ infield … [who has] never had a better season the one just closed.”3 That offseason, St. Louis traded for Miller Huggins, one of the era’s finest second basemen. Hauser’s chances for an immediate impact seemed slight as the Hulswitt-Huggins combo solidified in the Cardinals’ spring training.

Yet Bresnahan was a determined, energetic leader, and after his team stumbled to a 1-5 start, he shook up the lineup by inserting Hauser into the starting nine on April 23. Several days later, Bresnahan announced the youngster would be the Cardinals’ everyday shortstop. A newspaperman, seeing Hauser standing 5-foot-6 and weighing 145 pounds, interrupted: “But he looks to me like a little man.” The manager responded: “Yes, but he’s a little big man. He covers all kinds of territory. … He’s unusually well muscled for so small a man, is fast on his feet, accurate in his throwing, and has all kinds of steam behind his hits.”4

Bresnahan mostly placed Hauser’s right-handed bat eighth in the lineup that season. Hauser hit only .205, but proved adept enough at taking pitches and crowding the plate to earn a credible .312 OBP. It was his fielding, however, that made Hauser “one of the finds of the season” and a fan favorite in St. Louis.5

That July, a correspondent noted: “Hauser has of late taken to lofty tumbling and his springs into the air from which he comes down on a high liner that would have passed four feet over an ordinary shortstop’s head, and sometimes he does not, but the stunt, hit or miss, is well worth the price of admission.”6 On July 30, in a home game against the Cubs, Hauser made just such a sensational catch to start a triple play.

It happened in the top of the fifth, after Jimmy Sheckard singled and Solly Hofman beat out a bunt. Player-manager Frank Chance signaled a hit-and-run, and laced Frank Corridon’s first offering “on a line to the left of short stop and high up, but Hauser jumped sideways and stabbed the ball with one hand. It caromed off his mitt higher into the air, but he caught it before it reached the ground and Chance was out.”7 Sheckard was already on third, and Hofman heading into second. Had Hauser run over second and tagged Hofman, an unassisted triple play would have been his. But the rookie hesitated. Then, regaining his wits, and with a burst of adrenaline, Hauser planted his spike on Huggins’ foot as he stabbed the sack and threw the ball to first baseman Ed Konetchy, who nabbed Hofman.

Three Cubs were out – and one Cardinal, too, as Huggins left the game to tend to his wounded foot. Hauser, the Chicago Examiner proclaimed, is “the only living athlete now in captivity able to pull off a quadruple play.”8

The Cardinals finished at 63-90, their best finish (and best team attendance) in a half-dozen seasons. The team’s strength was its infield, with third baseman Mike Mowrey joining Hauser, Huggins, and Konetchy. Management provided Hauser with a hefty raise for the upcoming season.

St. Louis teams rarely contended in the Deadball Era. But the 1911 Cardinals soared a dozen games past .500 by midseason and competed with the Phillies, Giants, Cubs, and Pirates for the lead. Hauser got off to a hot start, too, and Bresnahan increasingly placed him second in the batting order, following leadoff hitter Huggins.

Contemporary accounts recognized Hauser’s bunting, speed to first base, and hit-and-run execution. He was crafty enough to pull the hidden ball trick, and scrappy enough to fight (the similarly diminutive) Johnny Bates in an April battle with the Reds. Hauser led the league’s shortstops in errors, just ahead of Chicago’s Joe Tinker and Philadelphia’s Mickey Doolin, elite defensive shortstops who ranked first or second in all other defensive categories. At the same time, however, Hauser climbed into the top five in putouts, assists, double plays, and fielding percentage.

Still, both the Cardinals and their shortstop faded in the 1911 competition. The team finished in fifth place, with a 75-74 record. Hauser finished with a .241 batting average, .286 OBP, and .311 SLG.

That September, Hauser married Winifred Sweeney on her twentieth birthday. Miss Sweeney lived within a block of the Cardinals’ Robison Field, and the two apparently met at the ballpark. The newlyweds settled in St. Louis. Daughter Mary arrived the next year.

The Cardinals fell backwards in 1912, finishing in sixth place with a 63-90 record. Bresnahan’s emotional and demanding style may have run its course with his players. He battled with team owner Helene Britton, who dismissed him at the end of the season. The team’s pitching staff also struggled, with The Sporting News noting in mid-season that “only poor pitching has kept them out of it and no further alibis are being sought by Roger’s flingers.”9

On June 5, Arnold Hauser’s widowed mother Mary committed suicide by swallowing poison in her daughter’s Chicago home. Poor health reportedly caused the act. Hauser was in Philadelphia, where the Cardinals beat the Phillies that afternoon. Team management notified him after the game, and he promptly left for Chicago. Hauser returned to the Cardinals two weeks, and ten games, later.

Even with the tragic interruption, Hauser continued to improve in 1912. He finished the season with a .259 average, .319 OBP, and .324 SLG. He made similar progress in fielding: his chances, putouts, assists, and fielding percentage all increased significantly from his 1911 numbers.

After the 1912 season, rumors suggested both the Giants and the Cubs sought Hauser. The Chicago deal seemed more likely, with newly appointed Cubs manager Johnny Evers reportedly offering his longtime double-play partner Joe Tinker even up for Hauser. Huggins, whom Britton appointed to succeed Bresnahan as the Cardinals manager, squashed any such deal.

That offseason, playing indoor baseball, Hauser “twisted his [right] knee sliding on a wooden floor.”10 This incident was not reported, nor is there any indication the Cardinals knew of it. Hauser, who signed a new contract before reporting to the team’s 1913 spring training, may well have been quietly rehabilitating, hopeful his knee would mend.

In Columbus, Georgia, on March 4, however, Hauser slid into second base during a Cardinals practice game. His spikes caught the bag, and the same right knee gave way. The initial diagnosis was a torn ligament. Huggins brought in the aging Charley O’Leary to fill in at short. Hauser did not return to game action until the beginning of June. His range in the field was limited, and he was often used in a pinch-hitting role.

On June 24, Arnold and Winifred suffered the loss of their daughter Mary. Missouri death records indicated the cause as an “enlarged thymus gland.” The tragedy went seemingly unreported at the time. After a brief leave of absence, Hauser returned to the team, and soldiered on. After additional examinations, surgery was performed on his knee at Johns Hopkins in mid-July. With Hauser’s 1913 season shut down after just 22 games, the Cardinals footed the bills for his medical care, continued to pay his salary, and allowed him to quietly grieve away from the public’s eye.

Cautiously, the Cardinals sent their embattled shortstop to their St. Augustine, Florida spring training site in early February 1914, accompanied by the team groundskeeper. When the rest of the team arrived at the end of the month, it was clear Hauser had taken a turn for the worse. Since the fall he had lost twenty-five pounds, reportedly to pneumonia. Hauser was listless, kept to himself, rarely expressed any happiness, and exhibited signs of delusion. Doctors assessed him as “a victim of melancholia with a religious trend.”11

Winifred traveled to Florida. After three weeks the exhausted young wife took her husband home to St. Louis, where he was promptly placed in a sanitarium. Hauser’s misfortunes – his mother’s suicide, his devastating injury, his daughter’s death, and his psychological collapse – were now being reported across the country.

As Hauser remained under treatment, his case became increasingly politicized. First, upon the full team’s arrival in St. Augustine in late February, club President Schuyler Britton (Helene’s husband, and mostly under her wing), had announced the Cardinals could no longer keep him on their payroll.12 Then, using Hauser as an example of their precarious careers, Cardinals and Browns players demanded a cut of the annual St. Louis spring series receipts a month later. The Cardinals donated receipts of an exhibition game to his care in April and, shortly thereafter, Helene Britton announced a lifetime pension for Hauser.

That summer, Federal League representatives visited Hauser at the sanitarium, hoping to sign him if he returned to form. The new circuit’s St. Louis franchise played a benefit game on Hauser’s behalf. Winifred Hauser wrote the wife of Rebel Oakes (formerly a Cardinal, now the player-manager of the Federal League’s Pittsburgh team) telling of uncaring actions from the Brittons and Huggins. In Mrs. Hauser’s letter, published in the press, she wrote that her husband’s physician “asked Huggins why he never inquired about or said anything in the paper about Arnold, and Huggins said: ‘I think Hauser is through,’ and turned his back and walked in the club-house.”13

Huggins, and the Cardinals, had moved on. After Charley O’Leary proved a poor substitute in 1913, and the team slid into last place with a 51-99 mark, Huggins handed the shortstop duties to young Art Butler in 1914. Butler proved an improvement over O’Leary. With the emergence of Pol Perritt and Bill Doak on the pitching staff, St. Louis enjoyed a surprising 81-72 third-place finish.

By June 1915, Hauser’s health had improved enough that he was released. He worked out with the Cardinals, although the team offered no public encouragement, and his doctors advised a change of scenery. The Federal League’s Chicago Whales, with Jimmy Smith struggling at short, obliged. After playing a couple semipro games in the city as an audition, Chicago signed him, and manager Joe Tinker placed Hauser in the starting lineup on August 12, as the Whales visited Newark.

Hauser’s comeback featured some touching moments. In his home debut with the Whales, on August 22, he was “called to the plate to receive a valuable chest of silver … an accumulation of quarters, which came from the amateur and semipro ball players of Chicago.”14 On September 6, in the second game of a doubleheader, Hauser played in St. Louis for the first time in over two seasons, before a crowd of 12,500. Hauser was presented with a traveling bag, and cheered when, playing third, he “made a sparkling catch of a foul ball off [Armando] Marsans’ bat in the first inning which reminded the fans of his stellar work of two years ago.”15

Yet, overall, Hauser’s play was unimpressive. Several days before the St. Louis return, he committed three errors in a loss at Kansas City, and Tinker signed Mickey Doolin to take over at short. Tinker used Hauser sparingly for the remainder of the season. In his comeback, Hauser batted .204, with a .283 OBP and a .222 SLG. He committed 11 errors in 16 games at shortstop.

During the offseason, Hauser’s services attracted no interest. The Cardinals unceremoniously released him in February 1916, and one can only wonder if the promise of a lifetime pension survived the baseball wars. The Three-I’s Hannibal Mules offered Hauser a tryout in April but, seeing that he “was threatened by ill health,” released him.16

Within a year, Hauser was a patient at Elgin State Hospital, a mental institution operated by the State of Illinois. Baseball was provided as a therapeutic outlet, and Hauser played for the hospital team. He was discharged as cured in early 1920, and lived with his sister in Chicago. But within two years, by her complaints to the police, Hauser was sent back to Elgin.

In 1915, some of the more lurid reporting of Hauser’s problems indicated his wife had died.17 Yet there is no specific reporting of Winifred’s death, nor any associated death records, from this time. There are faint, suggestive threads afterwards. In the May 30, 1924 Cook County (Illinois) Herald there is mention of “Mrs. Lange, formerly Mrs. Hauser … visiting old friends” in nearby Niles.18 City records for Elgin, in both 1920 and 1927, show a Winifred Lange married to a Henry Lange.

Arnold Hauser remained at Elgin State Hospital, with some periodic releases, until 1955. He then worked as a chef at the Mercyville Sanitarium in Aurora, Illinois. Hauser died in that city, of a heart attack, on May 22, 1966. He was buried in Chicago’s Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Sources

In addition to the sources noted in the endnotes, the author accessed Hauser’s player file at the National Baseball Hall of Fame Library in Cooperstown, New York, and the following online sites:

- ancestry.com

- baseball-reference.com

- chroniclingamerica.loc.gov

- fultonhistory.com

- genealogybank.com

- news.google.com/newspapers

- newspapers.com

- retrosheet.org

Notes

1 “Hauser in Asylum,” The Sporting News, April 9, 1914, 2.

2 Jim Sandoval, “Dick Kinsella,” The Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/kinsella, accessed April 4, 2014; “Good Scouts Save Money,” Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican, July 10, 1910, 16.

3 “Not Up To Promise,” The Sporting News, October 7, 1909, 4.

4 Joan M. Thomas, “Roger Bresnahan,” The Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/90202b76, accessed April 8, 2014; “Hauser Cinches Job on Cardinals,” Daily (Decatur, Illinois) Review, April 27, 1910, 5.

5 “Two Sevens Again,” The Sporting News, July 14, 1910, 4.

6 “Heat is to Blame,” The Sporting News, July 28, 1910, 4.

7 I. E. Sandborn, “Cubs are Lucky: Beat Cardinals,” Chicago Daily Tribune, July 31, 1910, Section 3, 1.

8 Charles Dryden, “Cubs Get Third Victory in Row over St. Louis by 4 to 1,” Chicago Examiner, July 30, 1910.

9 “No Room for Bobby,” The Sporting News, July 25, 1912, 4.

10 “Cards Manager Puts Ban On,” Watertown (New York) Daily Times, August 14, 1913, 6.

11 “Loss of Hauser Hits Cards Hard,” The Sporting News, March 5, 1914, 2.

12 Joan M. Thomas, “Helene Britton,” The Baseball Biography Project, http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/ecd910f9, accessed April 8, 2014; “Hauser Not Fit For Work,” Pittsburgh Press, February 27, 1914, 32.

13 “Not Even a Ball,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 4, 1914, 8.

14 J.J. Alcock, “Fed Fans Flock to Whales Park for ‘Brown Day,’” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 23, 1915, 9.

15 “Whales Defeat Terriers, 5 to 4,” Chicago Examiner, September 7, 1915.

16 “Arnold Hauser is Given Release,” (Decatur, Illinois) Daily Review, April 27, 1916, 5.

17 Within such reports, it was also commonly mentioned that two of his children had burned to death. Again, like Winifred’s death, there seems to be no contemporary reporting, or present-day genealogical evidence, that supports this. See, for an example of this reporting: “Hauser, Plaything of Misfortune, Back in Game,” (Philadelphia) Evening Public Ledger, June 15, 1915, 12.

18 “Niles Center News,” Cook County (Illinois) Herald, May 30, 1924, 1.

Full Name

Arnold George Hauser

Born

September 25, 1888 at Chicago, IL (USA)

Died

May 22, 1966 at Aurora, IL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.