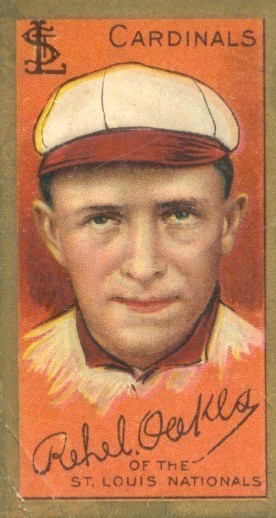

Rebel Oakes

“Now Ol’ Rebel Oakes come up from the South

With some tan on his face and a chew in his mouth;

When asked if he thought he could build up a team

That can drag down a pennant and fulfil a dream,

Ol’ Oakes, he say: ‘Mebbe so!’”1

Ennis Telfair Oakes was born in the “Arizona community” near Lisbon, Louisiana on December 17, 1883. He was the first of four children born to Joseph and Cordelia Oakes. Arizona was once a village, then a small settlement, and now but a faint memory in the north-central part of the state. Here the elder Oakes farmed, mostly cotton, for a living.2

Ennis Telfair Oakes was born in the “Arizona community” near Lisbon, Louisiana on December 17, 1883. He was the first of four children born to Joseph and Cordelia Oakes. Arizona was once a village, then a small settlement, and now but a faint memory in the north-central part of the state. Here the elder Oakes farmed, mostly cotton, for a living.2

His parents provided the means for Ennis to enroll in Louisiana Industrial Institute (present-day Louisiana Tech University) in nearby Ruston. Here, shortly after the turn of the century, Oakes starred on the school’s football and baseball teams.3 The youth made his professional debut with Hattiesburg of the Class-D Delta League in 1904. The “fleet- footed center fielder” started 1905 with Hattiesburg before moving to Greenville in the same league.4

Oakes spent 1906 and 1907 with Cedar Rapids of the Class-B Three-I League.5 Then he was signed by the Los Angeles Angels, and spent the 1908 season in the Class-A Pacific Coast League. In Iowa, Oakes gained a wife, marrying Edna Arnell in 1906. In California, he gained a nickname, from sportswriter Charles Van Loan. “Rebel” was not a term comfortably worn by many Southerners of his era, but he adapted to it easily, and would present himself as Rebel Oakes for the rest of his public life.6

Clark Griffith signed to manage Cincinnati in December 1908. Seeking youthful speed and an additional left-handed bat, he acquired the sandy-haired 25-year-old Oakes in February 1909. Standing 5-foot-11 and weighing 170, Oakes choked up considerably on an especially heavy bat, broke efficiently from the batter’s box to first, and moved “like a sprinter”7 in the field.

Oakes earned the center-field job, but sliding into second on June 6, he was almost certainly concussed in a collision with Brooklyn’s Whitey Alperman. Griffith kept him out for a few games. Oakes continued to perform well upon returning, his average peaking above .300 in late June.8 But headaches persisted, exacerbated by a hot summer. Oakes stopped hitting, and Griffith rested him for long stretches. When the season concluded, Oakes had played in 120 games, compiling a .270 batting average, .341 OBP, and .340 SLG.

At times, Oakes demonstrated blinding speed and daring. On August 6, against the visiting Giants, he ended a scoreless tie in the 10th by laying down a perfect bunt along the third-base line, taking advantage of two New York throwing errors, and flying all the way to home plate.9 But Oakes also struggled with breaking balls down in the zone.10 Defensively, Oakes played a very shallow center field, and made spectacular plays doing so. But too frequently, in the sunny Palace of the Fans outfield, balls flew over his head, leaving partisans to wonder “what a wonderful ballplayer he would be if he only played back farther in the outfield!”11

Griffith possessed a surplus of young outfield candidates, and on February 2, 1910, Oakes was shipped off to the Cardinals, along with pitcher Frank Corridon and Miller Huggins, for pitcher Fred Beebe and utility man Alan Storke. St. Louis player-manager Roger Bresnahan sought to upgrade his center-field position, the play of Al Shaw and Joe Delahanty having proven unsatisfactory in 1909.

Already the Rebel was emerging as one of the game’s more colorful characters. He sported “an inimitable Southern drawl,” and a motormouth: “so full of ‘pep’ that he can’t keep quiet 20 seconds at a stretch.”12 Oakes was one of the era’s sharpest dressers and quite popular with his peers. His native humorous boasting endeared him to the press. On a certain Georgian he said: “Cobb would be pretty fair, if he could field as well as I do.”13

Over his first three seasons in St. Louis, Oakes compiled a .266 batting average, .321 OBP, and .328 SLG. The Cardinals finished 75-74 in 1911, their first winning record in a decade. But the team slid backwards in 1912 to a 63-90 mark, and owner Helene Britton replaced Bresnahan with Huggins.

In 1913, the Cardinals sank into the cellar with a 51-99 mark. The team trailed the rest of the NL in attendance, with barely over 200,000 for the season. Reporting upon an “unclassified Federal League team [drawing] a better Sunday crowd than the National Leaguers at Robison Field,” that summer, The Sporting News concluded that “major league baseball has lost caste in St. Louis.”14

In such a lost season, Oakes led the team with a .293 batting average, and his .350 OBP was third among the regulars. Defensively, his 11 errors were the fewest he committed since his rookie season.

In January 1914, a Cardinals representative visited Oakes in Shreveport with a contract offering the same pay, $3300, as the veteran had earned in 1913. Oakes declined to sign, adding that he had not been contacted by the Federal League (which had announced itself as a major league in late 1913). But by early March, he had been contacted by, and signed with, the Feds’ Pittsburgh franchise. His new contract was for three years, at $4,600 annually.15

Oakes wired: “Manager Huggins: Have just signed with Federals. Good luck to you. Regard to boys.”16 The Cardinals were caught off-guard; they regarded their center fielder as one of the few blocks to be retained in the rebuilding efforts underway. Had Oakes let them know of the Pittsburgh offer, The Sporting News surmised, it was likely “they would have met it.” As he seemed uninterested in such negotiations, the paper concluded, “Oakes just naturally wanted to jump and that is all there is to it. Peace to his ashes.”17

After five years of service, Oakes had established himself as an average major leaguer, standing out on a mediocre team. The Federal League promised new opportunities. Rebel Oakes pursued them without looking back.

Few players jumped so unequivocally. Oakes stated the salary offer as his motivation.18 Yet he proved uninterested in using the baseball wars to leverage his pay upwards. In his 1915 affidavit filed in the anti-trust suit brought against Organized Baseball by the Federal League, he expressed a knowing dissatisfaction with the 10-day clause and the general lack of player rights in his era. At the same time, there is no indication of strong ideological principles driving his actions. Finally, while the St. Louis contract offer had a clause forbidding the “excessive use of intoxicating liquors,” this was unlikely the cause of any great offense.19 Oakes was no teetotaler, but unlike teammate Slim Sallee, he was not identified by the press as having an alcohol problem.

Even before the 1914 season began, the Pittsburgh team Oakes joined was off to a slow start. After other candidates fell through, Doc Gessler was named manager in February. Strong financial backing, in the form of local businessman Edward Gwinner, was finally achieved in March. Besides Oakes, the team’s prized recruits promised little spark: outfielder Davy Jones was past his prime, and pitcher Howie Camnitz reported to camp in poor shape.20

Whether the Rebels were named in honor of Oakes is debatable.21 But after the team stumbled to a 4-11 start and Oakes replaced Gessler, they were his team. Pittsburgh began to win, and by June 8 climbed within four games of the league lead with a 20-21 mark.

The Rebel in charge relied on an everyday lineup in which only 29-year-old first baseman Hugh Bradley was under 30. So Oakes appealed to veteran sensibilities: “I tell my players that anything they want to do before 11 o’clock each night I’ll help them do it; but they’ve got to chop off at 11 and hit the hay. They also must have their eggs by 8:30. All the rest of my rules can be written on the wrong end of a pin.”22

But, as Robert Peyton Wiggins observes in his study of the Feds, “Oakes’s team just didn’t have the talent of some of the other Federal League clubs” in 1914.23 Then, after the springtime surge, injuries overcame the Rebels. By late August, one correspondent noted, the regular lineup had been in place for only 14 games.24 Pittsburgh finished in seventh place with a 64-86 record. Oakes led the team with 145 games played, finished among the league leaders with a .312 BA and 237 total bases, and in several defensive categories.

The Rebels drew poorly, with contemporary estimates for attendance at Exposition Park ranging from 60,000 to 76,000. But, four miles east at Forbes Field, the Pirates’ attendance plummeted from 296,000 in 1913 to 139,620 in 1914. Gwinner was confident he had the right man to lead the fight for Pittsburgh allegiances.

Oakes marketed the team with ease. This might involve charming Pittsburgh YMCA workers with a two-hour talk on the topic, “What Good is a Three-Bagger If You Don’t Score?”25 Or it might mean playing press agent, promising in September 1914: “the players I have lined up for 1915 will be one of the greatest aggregations that ever graced a diamond.”26

Indeed, Oakes was re-engineering his lineup with a relentlessness that any modern-day general manager would admire. As early as August 1914, he announced three additions: second baseman Steve Yerkes, shortstop Marty Berghammer, and pitcher Pol Perritt. Yerkes had just been released by the Red Sox, and promptly joined the Rebels. Berghammer jumped from the Reds; Perritt from the Cardinals. Both signed contracts to play in Pittsburgh in 1915. Then Frank Allen was induced to jump from the Dodgers. Oakes had lacked any left-handed pitching, and Allen would prove the winningest southpaw in the league the next season.

After the season concluded, Oakes upgraded his infield’s corners. Former Cardinal Ed Konetchy, who was traded to the Pirates before the 1914 season, jumped to play first base for his old teammate. For third, the Browns’ Jimmy Austin was recruited. To supplement Claude Berry behind the plate, catcher Paddy O’Connor was lifted from the Cardinals.27

Some jumped back: Perritt, Austin. Others were courted, but never landed: Heinie Groh, Dode Paskert. Then there were friends–Home Run Baker, Ty Cobb–who, if they happened to meet Oakes one day, became possible jumpers. “Oakes,” noted one observer of the unfolding action, “has well earned the title of ‘Chief Raider’ of the Federal League.”28

More change came in early 1915. Outfielder Jim Kelly, formerly of the Pirates, was landed by Oakes after a couple months of negotiation. Another former Cardinal, Mike Mowrey, who had been dealt to the Pirates with Konetchy, was signed to take over third after Austin slipped away. Then, to bolster his pitching staff, Oakes whisked away two youngsters from Toronto of the Class-AA International League: left-hander Bunny Hearn and right-hander Clint Rogge.

To address an unsettled left-field situation, Oakes bought Al Wickland from the White Sox in June. That completed the rebuilding effort. Center fielder Oakes and catcher Berry were the only regular position players from the Rebels’ debut season to retain their roles the next campaign. Elmer Knetzer was the only holdover in the starting rotation. These two seasons were particularly fluid ones in major-league history. But only in Cincinnati, where fiery Buck Herzog retooled the Reds, was any other team transformed to the extent Oakes overhauled the Rebels between the 1914 and 1915 seasons.29

The rebuilt Rebels were arguably the finest defensive squad in all of baseball, and middle-of-the-pack offensively. Oakes rarely tinkered with his everyday lineup. Allen, Knetzer, and Rogge ably led the pitching staff. Beyond that, Oakes struggled to find adequate starters. Sandy Burk jumped from the American Association and won a couple late-July games before a court injunction prevented him from additional service. Next came another AA jumper, Ralph Comstock, who provided assistance as a spot-starter from mid-August onwards.

By this point, Pittsburgh had fought back to the top of the race, battling with Chicago and St. Louis down the stretch. The Rebels’ season concluded with a six-game series versus the Whales. The teams split the first two games in Pittsburgh, then the scheduled October 1 game was rained out. On Saturday, October 2, Chicago swept a double-header.

At this point, with St. Louis eliminated, the Whales stood at 85-65 and the Rebels at 85-66. The two teams traveled to Chicago, with the matter of whether one or two games would be played on Sunday a point of contention. The league backed Chicago’s case for a double-header. The Whales needed to win only one of the two.

Pittsburgh pulled out the first in 11 innings. The second began with little more than an hour of daylight remaining. Knetzer and Chicago’s Bill Bailey hurled shutout ball as the shadows fell. When the Whales came to bat in the top of the sixth, it was likely their last chance: if the game ended as a scoreless tie, Pittsburgh would claim the title. With a man on third and two out, Max Flack smashed Knetzer’s 2-2 offering deep to center.

Oakes took after the drive, tracking the ball in the dusk, and headed towards the roped-in standing crowd along the perimeter of the outfield. For a costly moment, just short of the standees, he took his eye off the ball’s flight, and it “struck his glove and bounded out.”30 The run scored, then two more, before Pittsburgh was allowed one last chance in the seventh. To no avail. The game was called. Pittsburgh lost the game, 3-0, and the pennant.

On December 22, a peace accord was reached, and the Federal League went out of business. Gwinner put Oakes on the open market, with the price negotiable. Neither the Reds nor the Cardinals, both languishing in the National League depths, had any interest in their former outfielder. Nor did the Indians and Yankees, both second-division residents in the American League. Oakes had admirers in Pittsburgh, but Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss bluntly rejected their advances.31 In 1916, under first-year manager Jimmy Callahan, the Pirates suffered through their worst season in two decades.

Baseball historians have noted that, but for the outcomes, the Federal League’s fight was no different from the American League’s at the turn of the century.32 But whereas Connie Mack, Jimmy McAleer, and Clark Griffith built success from their piracy, Rebel Oakes was effectively blacklisted for his.

On March 15, 1916, the Denver Bears of the Class-A Western League signed Oakes as player-manager. (Gwinner assumed the difference between his present contract obligations to Oakes and Denver’s salary offering.) The Bears were a young team that had competed for the league pennant the season before. But the new manager for 1916, Doc White, resigned for personal reasons shortly before spring training. Oakes was consequently an emergency hire, and the team tumbled into the cellar with an 8-18 record by late May.33

Gradually, Oakes turned the team around, and the Bears finished in fourth place, with a 78-75 record. The team hit and fielded well, but had subpar pitching.34 Oakes himself finished with a .342 batting average, fifth-best in the league.

In 1917, Denver failed to progress. On July 4, with the team at 35-36, Oakes was relieved of his managerial duties, but remained with the Bears as a player for another month.35 He then played with Indianapolis of the Class-AA American Association for a few weeks, hitting only .143. In 1918, he played for the Wilmington squad in the Bethlehem Steel League. Then Oakes hung up his spikes and returned to north-central Louisiana, embarking on a new career in oil exploration.

In August 1919, reports indicated Oakes had been instantly lifted to millionaire status by a huge oil discovery. Soon he was in Pittsburgh, allegedly offering Dreyfuss a million dollars for the Pirates. Alas, his old foe wanted a half-million more. Next Oakes looked into buying the Phillies, Cardinals, and Braves.36

But Rebel Oakes was no millionaire. The oil strike had occurred on land belonging to Guy Oakes, his cousin. Instead, likely in an attempt to heal old wounds, Rebel played out an alternate version of reality. By 1921, he was toiling again as a player-manager, this time with Jackson of the Class-D Mississippi State League.

Oakes then returned to chasing the fickle fortunes of oil. His marketing and money-raising skills were renowned. Oakes built a lasting reputation in the oil fields as an intrinsically honest and industrious businessman.

Finally, in 1936, Oakes hit a jackpot, bringing in the first riches from the Lisbon Oil Field. But Oakes was an independent operator with limited access to deep capital, and quickly needed to open more wells to exploit his good fortune. Major players–such as Magnolia Petroleum–with these means moved in immediately. Oakes could only sell away, one after another, his leases in an effort to keep up, and the time frame for flush production was narrow.

Thus oil wealth, just as a baseball had years ago in a Chicago evening, slipped through the grasp of Rebel Oakes. When he passed away, on March 1, 1948, from pneumonia, Oakes was broke. He had split up with Edna years earlier, and was survived by his second wife, Sybil. Neither marriage produced any children. Oakes was buried in the Rocky Springs Cemetery in Lisbon, Louisiana.

Sources

The author is grateful to John D. Caruthers Jr. for sharing his knowledge of Oakes’s oil career. (Mr. Caruthers’s father, John D. Caruthers Sr., partnered with Rebel Oakes in the Lisbon Oil Field.) Additionally, the author thanks Wesley Harris for providing additional details of Oakes’s early days in Lisbon beyond that in his “Tech’s First” article.

In addition to the sources noted in this biography, the author also accessed Oakes’s player file from the National Baseball Hall of Fame, and the following sites:

chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/newspapers/

John D. Caruthers Jr., telephone interview with the author, July 14, 2014.

Notes

1 Gene Fowler, “Bear Facts,” Denver Post, March 23, 1917: 16.

2 Oakes’s family history, as provided through Ancestry.com records, may be supplemented with Sam Mims, Oil Is Where You Find It (Boston: Marshall Jones Company, 1940). The author also received support towards some of these details from Wesley Harris, email correspondence, July 1, 2014.

3 For discussion of his college days, see Wesley Harris, “Tech’s First,” Digging the Past, http://diggingthepast.blogspot.com/2011/04/techs-first.html, accessed October 5, 2014.

4 Delta Democrat-Times (Greenville, Mississippi), July 26, 1905: 1.

5 There were other players named “Oakes” in this stretch, but Ennis Oakes was under contract to the Cedar Rapids team for both seasons, and Midwestern newspapers consistently place him in the box scores of the team throughout both the 1906 and 1907 seasons.

6 On the sensitivity of Southerners to the term, see Gaines M. Foster, Ghosts of the Confederacy: Defeat, the Lost Cause, and the Emergence of the New South, 1865-1913 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987), 118. Oakes’s father, incidentally, was born in 1852, and consequentially too young to have served in the Civil War.

7 On these aspects: “Many Vagaries in Batters and Bats,” Plain Dealer, April 17, 1910: 23; “Gerner Taught How to Swing, Then Led League in Batting,” Cincinnati Post, March 23, 1917: 9; Jack Ryder, “First Game,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 11, 1909: 4; Jack Ryder, “Vigorous,” Cincinnati Enquirer, March 9, 1909: 4.

8 Contemporary sources: Oakes was batting .309 in the statistics presented in Evening Review (East Liverpool, Ohio), June 14, 1909: 6; .312 in Inter-Ocean (Chicago), June 27, 1909: 28.

9 “The Best Play I Ever Saw,” Chicago Tribune, August 7, 1913: 15.

10 A. R. Cratty, “In Pittsburgh,” Sporting Life, August 14, 1909: 7; Jack Ryder, “Long Bob’s,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 19, 1909: 8.

11 “Harry Gaspar Will Lead the Redleg Pitchers This Season,” Cincinnati Post, September 27, 1909: 6.

12 “Waiting is Over,” The Sporting News, March 24, 1910: 4.

13 “Chivalry Causes Spurt,” Star-Journal (Sandusky, Ohio), August 10, 1911: 8.

14 “Harpoon for Browns,” The Sporting News, July 3, 1913: 4.

15 See the Oakes and Schuyler Britton affidavits from the 1915 The Federal League of Baseball Clubs vs. The National League, et al. available via http://sabr.org/research/1915-Federal-League-case-files accessed October 5, 2014.

16 “Loss if Hauser and Oakes Will Crimp Cardinals,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 5, 1914: 17.

17 “Britton Real Hero of Battle at Dock,” The Sporting News, March 12, 1914: 4.

18 “Federal League Notes,” Sporting Life, June 20, 1914: 13.

19 Britton affidavit, 2.

20 For this background, see Robert Peyton Wiggins, The Federal League of Base Ball Clubs (Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland, 2009), 117-119.

21 Wiggins, Base Ball Clubs, suggests the team was already being called the Rebels. Daniel R. Levitt, The Outlaw League and the Battle that Forged Modern Baseball (Lanham, Maryland: Taylor Trade, 2012), 62-63, suggests the team was named after him.

22 W.J. O’Connor, “Reb Oakes Turns Tail-Ender into Winner in Month,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, June 9, 1914: 14.

23 Wiggins, Base Ball Clubs, 121.

24 Harry H. Kramer, “The Pittsburgh Rebels,” Sporting Life, August 29, 1914: 13.

25 William A. White, “The Pittsburgh Prospects,” Sporting Life, October 3, 1914: 17.

26 “Oakes Claims Winner in 1915,” Charlotte News, September 17, 1914: 19.

27 For these moves, see Wiggins, Base Ball Clubs, 164-167; “Renew: Raids on Organized Ball,” Muskogee Times-Democrat, August 3, 1914: 11; “Allen to Federals,” Fort Wayne News, October 9, 1914: 12.

28 William A. White, “The Rebels’ Infield,” Sporting Life, December 26, 1914: 9.

29 This analysis per the starter listings within Baseball-Reference’s Team Encyclopedias. The most stable team in major-league baseball between 1914 and 1915? By this standard, it was Clark Griffith’s Washington Senators.

30 “Flack Hero in Last Fed Game,” The Courier (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), November 24, 1918: 2.

31 Lack of interest from the Reds: “Oakes Willing to Play for Less,” Pittsburgh Press, February 4, 1916:36; Cardinals: “Caught on the Fly,” The Sporting News, December 16, 1915: 6; Indians: “Facts About the Federal League,” Sporting Life, February 12, 1916: 7; Yankees: “Chase Taboo in American,” Pittsburgh Press, January 26, 1916: 24; Pirates: A. J. Cratty, “Pittsburgh Pennings, Sporting Life, January 8, 1916: 7.

32 Harold Seymour, on this matter, is quoted in Wiggins, Base Ball Clubs, 6.

33 Lincoln Star, May 25, 1916: 10.

34 Denver Post, September 16, 1916: 7.

35 Denver Post, July 4, 1917:10.

36 Interest in the Pirates:Evening News (Harrisburg, Pennsylvania), January 15, 1920: 11; Cardinals and Phillies: “Rebel Oakes Tried to Buy Pittsburgh,” Charleston News and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina), July 5, 1920: 6; Braves: “What, Again?” Boston Post, February 21, 1921: 22.

Full Name

Ennis Telfair Oakes

Born

December 17, 1883 at Lisbon, LA (USA)

Died

March 1, 1948 at Lisbon, LA (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.