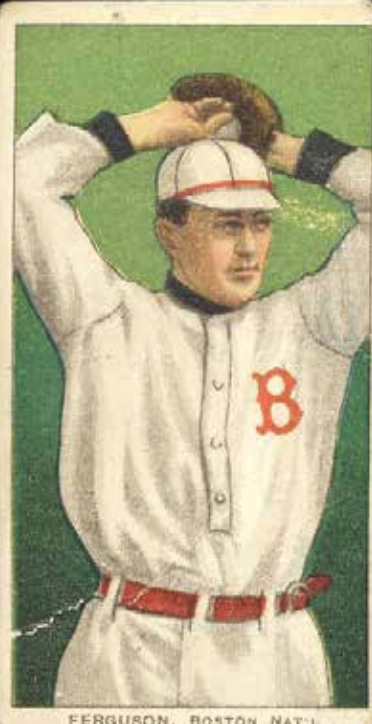

Cecil Ferguson

On October 1, 1906, Cecil Ferguson delivered a solid pitching performance for the New York Giants, shutting down the St. Louis Cardinals in the back end of a doubleheader, 2-0. The nightcap was a scheduled five-inning affair, and as noted in the New York Times, “the St. Louis team was completely at the mercy of Ferguson, making only two safe hits.”1

On October 1, 1906, Cecil Ferguson delivered a solid pitching performance for the New York Giants, shutting down the St. Louis Cardinals in the back end of a doubleheader, 2-0. The nightcap was a scheduled five-inning affair, and as noted in the New York Times, “the St. Louis team was completely at the mercy of Ferguson, making only two safe hits.”1

The start was the first of Ferguson’s rookie season and major-league career. Under the tutelage of manager John McGraw, Ferguson had previously been used exclusively as a “rescue pitcher,” a role fulfilled for the Giants in 1905 by Claude Elliott, when Elliott was credited with six saves (This statistic was first adopted by the major leagues in 1969, but baseball researchers have calculated many statistics retroactively.)

Ferguson posted a major-league-leading seven saves in 1906 after being acquired in August 1905 by the Giants from Louisville of the American Association for a player to be named later. That trade was finalized in April 1906, when New York sent Elliott to Louisville and, in effect, traded one “rescue pitcher” for the other.

The onset of the 1906 season was a cold, wet spring training in Memphis in March, which included a bout of diphtheria for Giants ace Christy Mathewson. But high expectations traveled north as the Giants, World Series champions in 1905, arrived in New York to play some preseason exhibition games at the Polo Grounds. The next day, the New York Times summed up McGraw’s hopes for Ferguson:

“McGraw is enthusiastic over the showing of the young Ferguson, whom he secured from Louisville in exchange for Claude Elliott. He believes the young fellow has all the attributes of a successful pitcher, and lacks only experience to whip him into such shape that he will be able to take his turn with the rest of them. He is cool headed, it is said, and ought to make good soon, though the entry of a young pitcher into major league company is the most precarious speculation known to baseball. The younger Mathewson [a comparison to Christy] has not done so well, although he has the physique to develop into a first-class man, and with careful tuition and training ought to do something. He is too young yet to expect very much of him, being only 18 years of age.”2

In actuality, Ferguson was 22 years old at the time, but with no official major-league experience, he was relatively unknown and certainly unproven. That would change.

Cecil Benoni Ferguson was born on August 27, 1883, in Ellsworth, Indiana, the second of four sons of Ellis Ferguson, a farmer, and Catherine (Trublood) Ferguson. (His birthplace was not the town of Ellsworth in Dubois County that now sits underneath the Pakota Reservoir, but rather the small town of Ellsworth in Vigo County that is now known as North Terre Haute.3

As a boy growing up in Ellsworth, Ferguson was considered one of the area’s finest all-around high-school athletes, playing fullback on the Terre Haute High School football teams that went unbeaten in 1901 and 1902.4 Before graduating from high school, Ferguson signed a pro baseball contract with Terre Haute’s 1902 Class-B Three-I League team, the Hottentots, but was released in June.5 Subsequently, he spent the summer of 1902 with the Lansing Senators of the Class-D Michigan State League, until the league disbanded in August.

The following season, still just 19 years old, Ferguson signed with the South Bend Greens of the Central League, a rival of the Terre Haute team that had cut him loose the previous year. The acquisition wasn’t without contention, as league President George W. Bement had to rule in a dispute between South Bend and Terre Haute over the rights to Ferguson.6 Bement ruled in favor of South Bend, and Ferguson rewarded the Greens with a solid season, leading them to a close second-place finish behind Fort Wayne. The final standings were actually disputed by his club, and despite multiple claims that results were inaccurate and percentages miscalculated, Fort Wayne was officially proclaimed the champion by President Bement. The teams played a postseason series of no consequence to the standings or the championship, but a side bet was arranged by the players on each side. South Bend won three games with one tie, with Ferguson’s arm accounting for one of the victories.

In consideration of his strong showing in 1903, Ferguson, who had earned $150 monthly, returned his contract unsigned for the 1904 season with a request that his salary be raised to $200. The strategy didn’t work, however. Central Baseball League managers were attempting to lower salaries throughout the league; Ferguson eventually signed for $125 monthly and rejoined the Greens for the 1904 season.7

His showing in 1904 continued to rate him a solid prospect, and although South Bend finished a distant third in the standings, Ferguson’s contribution continued to be of notice. The Fort Wayne Evening Sentinel ran a feature in June 1904 headlined “A Young ‘Phenom’ Who Delivers the Goods,” and noted that “Ferguson is a good man and looked upon generally as big league timber as soon as he is a little better seasoned.”8

In late July, George Tebeau, president of Louisville Colonels of the American Association, purchased four players from South Bend. Ferguson was among them, and joined the Louisville team on September 8, four days before the close of the Central League season. The Colonels swept both ends of a doubleheader against Toledo on September 11, with Ferguson striking out nine in a 7-2 victory in the nightcap that was called after five innings because of darkness.9

The following season, 1905, again with Louisville, Ferguson appeared in 43 games for the Colonels, posting a 14-18 record with 313 innings pitched. Although he lost more games than he won, he continued to be noticed despite his team’s futility.10 Ferguson, identified as a prospect by the Giants’ McGraw, finished the season with the Ohio Works club of Youngstown, awaiting his ascent to the major leagues as the Giants finalized a deal with Louisville.

The Giants had five established starters, Ferguson joined the team in 1906 with limited fanfare. As noted earlier, his only start late in the schedule was a quality one, but McGraw used him almost exclusively as a reliever throughout the season. In an early appearance in June, Ferguson gave up 14 hits in seven mop-up innings, after the Giants starter surrendered 11 runs in the first inning of a 19-0 loss to Chicago.11 But the appearance proved to be an anomaly, and although not an accredited statistic at the time, Ferguson’s seven saves led the league, and he posted a respectable earned-run average of 2.58 over 52⅓ innings in his rookie season.

Ferguson was used as a starter in early 1907, and posted a 3-1 mark through his first four games. But a poor outing on June 24 against the Boston Doves included five hits, four walks, and two wild pitches in the first three innings of a 10-8 loss. Ferguson did not start another game as a Giant. For the season, he again posted a respectable earned-run average of 2.11, but he appeared in only 15 games and posted a single save. Not only did New York finish 25½ games behind the Cubs in the final standings, but McGraw, who earlier considered sending Ferguson back to the minor leagues to improve his control,12 now sought greater changes. On December 13, 1907, McGraw traded Ferguson along with Frank Bowerman, George Browne, Bill Dahlen, and Dan McGann to Boston for Al Bridwell, Tom Needham, and Fred Tenney. Ferguson would wear a Boston Doves jersey in 1908, a team name adapted from the Dovey brothers (George and John), who now owned the club formerly known as the Beaneaters.

If not for the St. Louis Cardinals in 1907, Boston would have finished in last place in the National League. The infusion of new players moved the Doves up a spot in 1908, and Ferguson was placed in the regular rotation, starting 21 games and completing 13. On June 12, in a home win over Cincinnati, he put together perhaps his greatest performance to date. Jack Ryder ofthe Cincinnati Enquirer described it as follows:

“It was a desperate contest all the way. The Reds played cleaner ball on the defense than the Doves, and have not lost their aggressive spirit, but they were perfectly powerless in the hands of Ferguson. The big fellow had ’em winging for fair. Any twirler who can hold our famous sluggers to two stingy hits is going some and is entitled to a prominent place in the baseball hall of fame. Fergy had the Ganzel group completed dazzled. He used speed, curves and a tantalizing slow ball copied after Dr. Coakley’s, and not one of his brands was hittable. His wide curve especially was an awful fooler, and the best batters on the team were deceived over and over again into standing calmly by and letting good ones split the plate without offering at them. At other times they were caught in the act of swiping wildly at balls a foot or two from the plate. Whether they struck or did not strike it was all the same, for Fergy had them either way.”13

Five days later, Ferguson walked four in 1⅓ innings in a 14-4 loss to Pittsburgh. It was reported that he snapped a ligament in his arm, and he was sent to the prominent therapist and healer Bonesetter Reese in Youngstown, Ohio, for treatment.14

Whether rest or treatment made the difference, Ferguson’s first game back, on July 27, resulted in a 6-0 complete-game victory over Cincinnati, and he followed that performance with another complete game, scattering five hits in a 14-0 drubbing of Chicago on August 1. The Doves were 16 games out of first place by this point, with no hope of competing for the pennant. Ferguson won five more games before the season was over, and finished the year with an 11-11 record and another effective ERA of 2.47.

After the moderate success of the 1908 season, 1909 looked promising for Ferguson, who was still only 25 years old when the season began. An Opening Day start resulted in a 9-5 victory over Philadelphia, and the optimism was further validated early in the season when Boston traveled to New York and Ferguson stymied his former mates with a complete-game, two-hit shutout in a 10-0 thrashing at the Polo Grounds. The New York Times recapped the domination in this fashion: “It may have been indicated above that the Giants were defeated at the Polo Grounds yesterday afternoon. They made no runs themselves, but the Doves raced across the home plate so fast and so often that the afternoon papers disagreed as to how many tallies they did really make. One paper said nine. Most of the others said ten.”15

With the victory in New York, Boston was first in the standings, and Ferguson was 2-1 in the young season. But the Doves lost 10 of Ferguson’s next 11 starts, and on June 25 occupied the National League cellar, 27 games behind the Pirates.

Ferguson rallied in his subsequent two outings, tossing back-to-back shutouts against Philadelphia, 1-0 and 4-0. But the Doves were a hapless bunch, and Ferguson was 1-11 in his next 12 starts. His final start, on September 13, against the Giants ended in a 4-4 tie after 13 innings, called due to darkness. With 23 games remaining on Boston’s schedule, Ferguson had seen his last start in 1909. Overall, he started 30 games, with 19 complete games. Boston won only 45 games, with Ferguson taking the loss in over half of those, and the Doves finished 65½ games behind the pennant-winning Pittsburgh Pirates. His final record was 5-23, with a 3.73 earned-run average.

With the disappointing season behind him, Ferguson was reported to be retiring, and announced in February 1910 that he was going into the grocery business in Ellsworth (North Terre Haute).16 But the plan was abandoned, and he signed with Boston in March for another season.17

The 1910 season saw a decline in the Doves’ utilization of Ferguson. He did complete 10 games among 14 starts, and although he posted a respectable 7-7 record, his innings pitched declined by more than 100 from the year before. Boston again finished last in the National League, losing 100 games.

Despite the statistical mediocrity displayed by Ferguson and the lackluster results of the Doves in general, Ferguson was credited with having perhaps the most peculiar assist made in the 1910 season, as noted in multiple newspapers, including the Brazil Times, a newspaper based just outside Indianapolis:

“The play came up late in the season in a game against Brooklyn and resulted in a victory for the Boston team. At least it prevented the Brooklyn team from taking the lead, and as Boston afterwards won the game, the chances are the play turned the tide.

“Ferguson was pitching. Both teams had been hitting hard and making many runs and Fergy was thrown in to save the day with a runner on third base and one out. He pitched well enough, but in spite of his efforts the batter drove a fly to Miller, who was over in deep left center. The runner held his base and the batter tore around first to race to second on the throw to the plate. Ferguson went over on the line between shortstop and the catcher, being ready to catch the ball and throw to second base in case he decided there wasn’t a chance to catch the runner going home. He decided at the last minute that Miller’s throw was good enough to catch the runner at the plate, and dodged quickly into a stooping position to let the ball go to Harry Smith, who was catching. But in dodging Fergy miscalculated the shoot of the ball, which darted downward, cracking him on the top of the head. Instead of losing the game, the accident won it, as the ball caromed perfectly off the pitcher’s pate into Smith’s hands and the runner was out at the plate by a foot.

“As Fergy came to the bench Manager Fred Lake cruelly remarked: “I’m glad to see you using your noodle at last.”18

Ferguson used his “noodle” again during the offseason. He was denied a $500 bonus from the Doves for winning half his games, the Doves claiming two of the 14 games were exhibitions. Ferguson appealed to the National Commission, which ruled in his favor, noting that the contract clause in relation to the bonus made no stipulation about what games he was to pitch. The Boston Club was ordered to pay the bonus.19

Meanwhile, George Dovey had died in 1909, and John Dovey and his partner sold the club to William Hepburn Russell, who renamed the team the Rustlers for the 1911 season.

Ferguson again announced he was leaving baseball for good in 1911, to remain in the plumbing supplies business which occupied his offseason hours, unless the new Boston management gave him his figure.20 He ultimately signed his contract, and his first appearance was a start on June 4 at Cincinnati. It was a disaster. Ferguson gave up six runs without registering an out in a 26-3 embarrassment. A week later, in Chicago, Ferguson gave up seven more runs (five earned) in a 20-2 loss to the Cubs. The newly characterized Rustlers already occupied the bottom position in the standings, 19½ games out.

Ferguson pitched respectfully in a June 22 relief appearance, holding the Giants to four runs in 7⅔ innings in an 8-7 victory.

A 5-0 loss on June 26, and a brief appearance in a loss to Cincinnati on July 6 were final gasps of Ferguson’s diminishing major-league experience. One final start on July 21, a 7-5 loss at home to Pittsburgh in which Ferguson allowed 11 hits in eight innings, would end the once promising career with a less-than-stellar 29-46 record.

Although not specifically noted as affecting Ferguson’s baseball exploits, his father, Ellis, was kicked over the heart by a horse in early June and died in July, the final month of Ferguson’s major-league career.21

His performance ineffective, Ferguson was sold by the Rustlers to Memphis of the Southern Association in late July. But Ferguson refused to report, staying in Boston and working out in hopes the Rustlers would recall him. He never saw action with Boston or any other major-league team the remainder of the schedule, and finally reported to Memphis for the 1912 season, when he fashioned a 9-18 record.22

One final sale, with Memphis shipping Ferguson to Venice (California) of the Pacific Coast League, closed out Ferguson’s days in professional baseball. His statistics showed a 1-6 record in 10 starts, but the season wasn’t without a colorful anecdote. In a start against Los Angeles, Ferguson was knocked unconscious by another ball to the head, the scenario described in the Los Angeles Times as follows:

“This brings us down to the nerve-racking round – the one in which Elliott [catcher] came near committing homicide on the head of Cecil Ferguson. Howard opened the second half with a sharp single over second. He started to steal on the next pitch. Elliott winged the ball on a line toward second with the speed of a Mauser bullet. Ferguson stooped to avoid the throw, and turned his head. The ball struck him on the cerebellum and caromed out to Carlisle in deep left.

“No one saw the direction of the ball, and Howard rushed to the plate unmolested. Ferguson staggered and slowly toppled back. He lay stretched into the middle of the diamond unattended until after Howard had scored.

The water bucket was rushed to the center, and a few applications of the cool contents brought Fergy back to his feet. The crowd, which had been looking on with something akin to horror, greeted his return to consciousness with a round of applause, while the official scorer charged Elliott with an error and an attempt to commit manslaughter.

“Cecil, being a game individual, held his aching head with his left hand and resumed pitching with his right. He was plainly groggy, and walked [Billy] Page. Billy swiped second, and Elliott, thoroughly unnerved, sent him along to third with a throw into centerfield, Ferguson flopping on his stomach to make sure of saving his head.”23

Despite a few appearances with Evansville back in the Central League in 1914, Ferguson was enrolled at the Kirksville (Missouri) Osteopath School with plans to become a physician. He coached the school’s 1914 baseball team; it won every game on its schedule, and he was re-elected baseball mentor for the following season.24

Ferguson completed his studies, and emerged as Dr. Cecil Ferguson, developing into a prominent physician for athletic injuries, primarily as an arm specialist. Working as a “bone-setter” in Terre Haute, he treated athletes from the University of Illinois football team, including Red Grange.25

Ferguson ultimately moved his practice to Miami, Florida, and treated such prominent players as Lynwood (Schoolboy) Rowe26 and Johnny Mize.27

A feature on Ferguson in 1942 summarized his contribution this way:

“You don’t see his name in a box score or on a club roster, but Dr. Cecil Ferguson has played a bigger role in the baseball pennant races in recent years than many a headliner of the game.

“Dr. Ferguson, a Miami osteopath, is a ‘Mr. Fix-It’ of the sports world. He is described by Guy Butler of the Miami Daily News as the nearest approach yet to Bonesetter Reese, the famous old miracle man of sports who ‘could fix anything from concussion to athlete’s foot.’ Himself a former pitcher for the New York Giants and Boston Braves, Dr. Ferguson in recent years has patched up some of the game’s greatest stars, including such luminaries as Bob Feller, Carl Hubbell, Gabby Hartnett and Johnny Mize, not to mention scores of top-notchers in other sports.

“Dr. Ferguson confides that it was none other than the great Reese who gave him that start. While still pitching, he went to Reese to have a kink in his arm fixed, became interested in Reese’s methods and later worked 18 months under him before starting out for himself.”28

Despite his lackluster career after initially showing so much promise, Ferguson found great notoriety treating the quality of athlete he once aspired to be.

Ferguson had three brothers, all of whom became accomplished in life, two also becoming physicians. His youngest brother, Ralph, preceded Cecil in Miami, and the two practiced together before dissolving the partnership in 1931, when both brothers decided to operate independently.29

Denzil, the third of four Ferguson brothers, was a longtime Vigo County coroner who was followed in his career by his son, Denzil Jr.30

Leslie, the oldest brother, owned a downtown men’s clothing store in Terre Haute and was the Vigo County recorder.31

While on a fishing trip, Ferguson suffered a heart attack near Montverde, Florida, and died at the age of 60 on September 5, 1943. He and his wife, Caroline (Lutz), who together raised two sons (William and Cecil Jr.), are buried in Woodlawn Park North Cemetery and Mausoleum in Miami.32

This biography is included in “20-Game Losers” (SABR, 2017), edited by Bill Nowlin and Emmet R. Nowlin.

Sources

In addition to the sources cited in the Notes, the author also accessed Retrosheet.org and Baseball-Reference.com.

Notes

1 “Giants Take Two Games,” New York Times, October 2, 1906.

2 “Giants Come Home for Real Baseball,” New York Times, April 7, 1906.

3 Pakota Reservoir Interpretive Master Plan 2009, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, https://in.gov/dnr/parklake/files/SP-Patoka_Lake_IMP2009.pdf, April 22, 2017.

4 Wabash Valley Visions & Voices Digital Memory Project, “Cecil Ferguson,” https://visions.indstate.edu:8888/cdm/singleitem/collection/vchs/id/271/rec/1, May 2, 2017.

5 I.-I.-I. League Affairs, “A Protest Against Defiance of a National Board Award,” Sporting Life, June 28, 1902: 5.

6 “Latest News from All Over the Central League,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, April 25, 1903: 2.

7 Sporting Life, March 5, 1904: 5.

8 “A Young ‘Phenom’ Who Delivers the Goods,” Fort Wayne Evening Sentinel, June 9, 1904: 2.

9 Associated Press, “Colonels Take Both Games,” Muncie (Indiana) Star Press, September 12, 1904: 3.

10 “Good Records in Baseball,” Louisville Courier-Journal, December 31, 1905: 29.

11 “Giants Badly Beaten,” New York Times, June 8, 1906: 7.

12 “May Release Giant Twirler,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, August 2, 1907: 7.

13 The Reds’ Batting Slump Comes Along With Bells On,” Cincinnati Enquirer, June 13, 1908: 3. “Dr. Coakley” presumably was Andy Coakley of the Philadelphia Athletics.

14 “National League News,” Sporting Life, June 27, 1908: 9.

15 “Boston Finds Weak Giants Easy Victims,” New York Times, April 28, 1909: 10.

16 “Diamond Chips,” Richmond (Indiana) Palladium and Sun-Telegraph, February 12, 1910: 2.

17 “No Grocery for Fergy,” Brazil (Indiana) Daily Times, March 16, 1910: 3.

18 “In the World of All Sports,” Brazil Daily Times, December 28, 1910: 3.

19 “National League Men in Session,” New York Times, December 14, 1910: 14.

20 “Big League Gossip,” Washington Herald, April 9, 1911: 17.

21 “Races in Four Baseball Leagues,” Baltimore Sun, June 8, 1911: 12.

22 “Sport Chat and Like O’That,” Zanesville (Ohio) Times Recorder, October 7, 1911: 10.

23 Harry Williams, “Tigers Take Fuzzy Game,” Los Angeles Times, September 11, 1913: 25.

24 “Palaver for the Fans,” Evansville (Indiana) Press, June 19, 1914: 8.

25 “Ferguson a Bone-Setter,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, November 20, 1924: 27.

26 “Doctor Studies Rowe’s Arm,” Des Moines Register, March 17, 1934: 6.

27 “Mize Goes to Sidelines,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, March 6, 1942: 34.

28 Wayne Oliver, “Dixie Sports Huddle,” Asheville (North Carolina) Citizen-Times, June 20, 1942: 10.

29 Dorothy Felker, “Surf Club’s Easter Ball Finale of Winter Events,” Indianapolis Star, April 5, 1931: 40.

30 Wabash Valley Visions & Voices Digital Memory Project, “Cecil Ferguson,” https://visions.indstate.edu:8888/cdm/singleitem/collection/vchs/id/271/rec/1, June 4, 2017.

31 Ibid.

32 findagrave.com, Cecil B. “George” Ferguson.

Full Name

Cecil Benoni Ferguson

Born

August 27, 1883 at Ellsworth, IN (USA)

Died

September 5, 1943 at Montverde, FL (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.