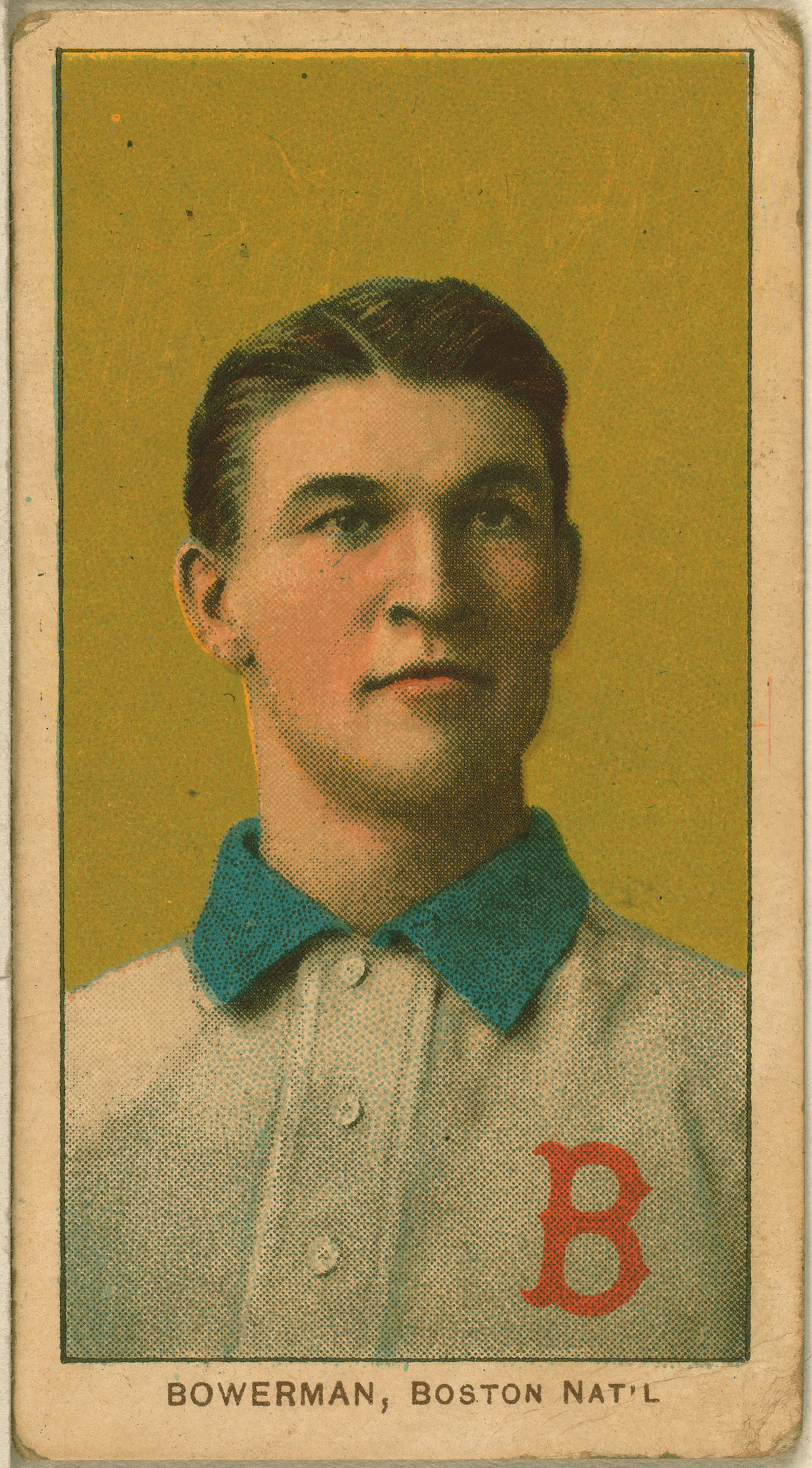

Frank Bowerman

Frank Bowerman’s major-league career spanned 15 seasons, from 1895 through 1909. It included stops with the Baltimore Orioles, Pittsburgh Pirates, New York Giants, and Boston Doves. Bowerman was a sturdy, robust player who stood 6-feet-2 and weighed approximately 190 pounds. Although known mainly as a catcher, the righty could play almost any position. Bowerman logged 132 of his 977 big-league games at first base. He also made a handful of appearances at the other infield positions, along with one in the outfield – he even pitched an inning for the Giants in 1904.

Frank Bowerman’s major-league career spanned 15 seasons, from 1895 through 1909. It included stops with the Baltimore Orioles, Pittsburgh Pirates, New York Giants, and Boston Doves. Bowerman was a sturdy, robust player who stood 6-feet-2 and weighed approximately 190 pounds. Although known mainly as a catcher, the righty could play almost any position. Bowerman logged 132 of his 977 big-league games at first base. He also made a handful of appearances at the other infield positions, along with one in the outfield – he even pitched an inning for the Giants in 1904.

Bowerman was a competitive man who played to the utmost of his ability, even when injured. He was aptly nicknamed “Iron Mike.”1 Aloysius “Wish” Egan, who went on to become a longtime Detroit Tigers scout, described Bowerman’s hard-nosed play and the toll of catching by referring to Frank’s battered hands (growing up, he played in the “bare hands” days before catcher’s mitts). “I don’t believe Bowerman had a finger on either hand that wasn’t twisted in some fashion. It wasn’t surprising since Frank was as game and hard a player who ever wore a baseball uniform.”2

Bowerman was popular with teammates, but he was also known as temperamental. He was ejected at least 10 times over the course of his major-league career. He repeatedly got into altercations with fans, players, and umpires. In one such case, during a game in Cincinnati, he was incensed at a heckler named Alfred Hartzell. Bowerman climbed into the stands, assaulted the music teacher, and bloodied his face. Bowerman was arrested and sent to a local police station but was released back to the ballpark before the Giants completed a doubleheader sweep of the Reds.3

He also had an ongoing feud with Pirates manager Fred Clarke, giving him a black eye and a beating in a ticket seller’s office at the Polo Grounds during one incident. Bowerman accused Clarke of attempting to foment dissension among Giant players with personal comments.4 Later in his career, Bowerman explained how the feud began during a game between Pittsburgh and Louisville. Clarke, then with Louisville, laid down a bunt and flung his bat at Bowerman’s throat as the catcher chased the ball. Bowerman retaliated by swinging Clarke’s bat at him. An ensuing melee was halted by local police.5

Bowerman’s physical toughness was on display off the field as well. On one occasion, he was driving a horse-drawn runabout that collided with an automobile in Harlem. He complained at the police station that the auto’s wheels ran over him and that the horse trampled on him in the ensuing confusion. Bowerman refused medical attention and the driver was charged with speeding.6

Before a game in New York, he fell under the wheels of a dray, which passed over his chest. George Gibson, former Pirates catcher and manager, recalled, “The big fellow arose and after standing for a few minutes until he regained his wind, he smiled and proceeded to the Polo Grounds.” When manager John McGraw inquired about the accident after the game, Bowerman told him, “Oh, it didn’t amount to anything. It hardly left a mark.” McGraw, dissatisfied, requested that the catcher remove his shirt. He noticed a wide tire imprint across his chest.7

Gibson also recollected another occasion where Pirate pitcher Howard Camnitz threw an inside pitch that struck Bowerman on his temple. Gibson remembered that the batter “dropped like a log; his fingers were twitching, and he was still unconscious when an ambulance drove right onto the Polo Grounds and took him away.” He added, “We were ready to send him flowers.”8 Several days later, teammates were surprised to see Bowerman appear at the Polo Grounds; he stated that he expected to be reunited with the team within a week or so.9

Frank Eugene Bowerman was born on December 5, 1868, in rural Romeo, Michigan, a village located about 40 miles north of Detroit. Frank was the first child born to parents Byron Bowerman, a farmer, and Mary Barnaby, a housekeeper. Over the next 11 years, the Bowerman family would add four more siblings: brothers George Burton and Harvey Seward and sisters Martha and Edna.

Beginning in 1888, at the age of 19, Bowerman played with the Logansport Oilers in the Indiana State League. Considered independent on the minor-league level, the league initially consisted of seven teams: Logansport, Elkhart, Fort Wayne, Frankfort, Lafayette, Marion, and South Bend. Although the league folded in midseason, Logansport finished first with a 10-3 record. A newspaper article published years later described Bowerman approaching the manager and requesting a team tryout. “The young fellow was not a promising looking athlete in his shabby clothes … but the (Oilers) needed a catcher, and the manager took a chance on the wanderer. He made good in the first game, and it was not long until he was taken by the Fort Wayne Club, which had a strong team.”10 The league revived itself as an eight-team conference in 1890, with Bowerman playing for the Fort Wayne Reds.

Bowerman’s emerging character managed to draw attention as well, off the baseball diamond. He and fellow Logansport teammate Albert Strueve were both arrested for associating with local prostitutes. Local press refrained from printing the ballplayers’ names, with one exception. C.O. Fenton, owner of the Logansport Times, informed team management that he would give the matter publicity in his paper. Strueve went to Fenton, protesting, only to pay a five-dollar bribe to settle matters. Bowerman took a different approach and refused to pay anything; as a result, his name was then publicized. Subsequently, rival papers gave the Fenton bribe “great prominence in the evening city papers.”11 Strueve announced that he would pursue prosecuting Fenton for blackmail.

Bowerman played baseball for two seasons at the University of Michigan in 1891–1892. In 1893, he joined the Detroit Athletic Club, which won a mythical world amateur championship.12 A year later, he joined the Detroit Creams in the Western League. He appeared in eight games and pitched in two, posting an 0-1 record and a 6.30 ERA.13

Bowerman married an Englishwoman, Viola Waite, on November 30, 1894. The couple resided in Washington Township, Michigan. They became the proud parents of a son, Edward Burton Bowerman, two years later in 1896.14

Bowerman’s career was in transition in the mid-1890s. In 1895 he was on the roster of the Twin Cities (Denison, Ohio) Hustlers in the Interstate League, which comprised eight midwestern teams. That year he made his major-league debut when he participated in one game with the National League’s Baltimore Orioles, going 0-for–1 at the plate. He did not get a hit until the following season, 1896, when he batted 2-for-16 (.125) in four games. That same year, he was listed on the Scranton Miners roster; he also played 20 games with the Norfolk Braves in the Virginia League (Class B).

The following year, 1897, Bowerman got the most playing time of any of his four years in Baltimore: 38 games under future Hall of Fame manager Ned Hanlon. He hit .315, which was his best single season batting average. The Orioles roster included exceptionally talented players. Bowerman was competing with two other catchers: another future Hall of Famer, Wilbert Robinson, and William Jones “Boileryard” Clarke (nicknamed for having a terrible voice). The absence of playing time included the Temple Cup, a post-season championship event in which the Orioles played from 1894-1897. Bowerman appeared in the last two games of the 1897 series, in which Baltimore prevailed 4 games to 1 over the Boston Beaneaters. He batted 3-for-3, including a triple, in Game Four.15 He participated in four double plays in Game Five.16 The Temple Cup series was terminated after the Boston series, owing to a decline in attendance and player and fan interest.

Bowerman played for the Pittsburgh Pirates in the 1898 and 1899 seasons. In June 1898, after appearing in just five games for Baltimore, he and Tom O’Brien were acquired from Hanlon’s club for $2,500. He subsequently saw action in 69 games for the Pirates.

In 1899, under second-year manager Bill Watkins, Bowerman appeared in 110 games, the most of any season in his career. In 1900, Pittsburgh absorbed 14 players from a disbanded Louisville roster, including manager Fred Clarke. (The National League was contracting from 12 to eight teams at the time.) While there may have been some residual enmity between Bowerman and Clarke, it appeared that the new manager was planning to take Bowerman and other survivors of the merger down to Thomasville, Georgia, for several weeks of preseason training in mid- to late March.17 The players were expected to use the time to get in shape for the 1900 season.

Following a National League owners’ meeting, Pittsburgh agreed to send one or two of their players to New York. Tom O’Brien and Bowerman were offered to the New York Giants, courtesy of Pirates owner Barney Dreyfuss.18 Clarke, however, doggedly pleaded with Dreyfuss to keep O’Brien on the Pirates roster. Dreyfuss agreed and Bowerman was released to the Giants on March 9, prior to Clarke’s trip to Georgia. It should be noted that Bowerman, having tried the first base position the previous season, did not do well, and had stated a desire to be dealt to New York.19

Bowerman’s time with the Giants lasted eight years, proving memorable on and off the field. He became a semi-regular catcher, splitting time with Mike Grady and Jack Warner in 1900, then sharing the load with Warner in 1901, 1903, and 1904. Warner jumped to the Boston Americans in 1902 and jumped back the following season. Meanwhile, Bowerman played 109 games in 1902, with George Yeager in reserve.

This period was highlighted by Bowerman’s association with future Hall of Fame pitcher Christy Mathewson, who also joined the Giants in 1900 as a rookie.20 Matty’s brilliant career would span 17 seasons, nearly all of it with Giants. Bowerman had the honor of catching Mathewson’s major-league debut and numerous other games. He earned much recognition for catching Matty’s “fadeaway” pitch. During the Giants’ rise to championship form during the 1903-1905 years, the ace was credited with 94 wins. In later years, Bowerman would declare, “Matty was a great pitcher – a really great one. He liked to have me catch him, and what a pleasure it was to be behind the bat when he worked!”21

The batterymates also socialized in the off seasons, with Matty traveling to Romeo for family visits22 and even semipro baseball contests. One such game reportedly used a “Charlie Smith” (Mathewson) to pitch for Romeo against another local area team for a Macomb County semipro championship.23

Bowerman also caught Luther “Dummy” Taylor, a deaf pitcher who taught his batterymate fingerspelling. They got along well, but Taylor jumped to the Cleveland Bronchos of the new American League at the beginning of 1902 season, joining other National League players who defected to the new American league. The Giants wanted Taylor back, dispatching Bowerman to locate the pitcher and persuade him to return to the team. Taylor received Bowerman’s overture and rejoined the Giants, winning his first game back on May 11 against St. Louis. This led Bowerman’s teammates to dub him “The Kidnapper.”24

Taylor’s successful return also led to a historic baseball event on May 16 in Cincinnati. On that day, he pitched against William “Dummy” Hoy, a deaf outfielder with the Reds. It was the only game in major-league history in which two deaf players opposed each other.

The Giants did not fare well during the first few seasons of the Deadball Era – but that would soon change after the arrival of John McGraw as manager two months after the Taylor-Hoy game. McGraw would last 31 years with the Giants, guiding the team to 10 National League pennants and three World Series titles. The skipper and the catcher, both temperamental, had their moments together, including personal fights. As Bowerman recalled, McGraw “never won a single one. I remember one day I knocked him down three times. That evening ‘Muggsy’ (McGraw) asked me to go to dinner with him. That’s how we played baseball in those days.”25

Baseball’s reputation and popularity often suffered during the 1890s and the early years of the Deadball Era. Because of the rowdy behavior of its participants, who often engaged in fisticuffs, profane language, and bullying of opponents, umpires, and fans, many spectators refrained from attending games. The American League evolved and was offered to fans as a wholesome alternative to the ruffian image of the National League. McGraw and Bowerman were emblematic of the older league. Having the wholesome Mathewson on the Giants roster was symbolic of public changes to the sport. He was baseball’s superstar at the time – good-looking, college-educated, polite, and possessing superb athletic talent.

However, on April 22, 1905, a Giants-Phillies game in Philadelphia was an example of how changes didn’t happen overnight. The Giants won, 10-2, but not before senseless fighting broke out in the eighth inning involving Bowerman, teammate Dan McGann – and even, allegedly, Mathewson.26

The incident began in the eighth inning when McGann rounded third base and attempted to score on a base hit by Sam Mertes. Left fielder Sherry Magee made a great throw to catcher Fred Abbott, who tagged McGann out at the plate without controversy. Yet for some inexplicable reason, McGann punched Abbott and the catcher retaliated by throwing the baseball at McGann’s rear end. Other players separated the two and umpire George Bausewine ejected both players.27 That should have ended the incident. However, after Bowerman entered the game to replace McGann at first base, Magee came to bat for the home team. He flied out, and while Magee was rounding first base, “Bowerman tried to bump him.”28

Fans, riled up by the incidents, became increasingly angry when a story made the rounds that Mathewson allegedly hit a small boy selling lemonade and that the boy threw his tray of lemonade back at the player.29 At this point many spectators left the park and gathered where Giant players were getting into barouches after the game to leave for their hotel meal. The crowd assaulted the open carriages with food, paper missiles and small stones. While there was some physical contact between individuals, the drivers and transports managed to flee the scene. Unfortunately, the entourage met another mob that was tossing stones. The Giants eventually escaped to the hotel.30

On June 13, 1905, Bowerman caught Mathewson’s second career no-hitter (the first had come on July 15, 1901, with Jack Warner behind the plate). The Giants beat the Chicago Cubs, 1-0, besting the Cubs battery of catcher Johnny Kling and pitcher Mordecai (Three Finger) Brown.31

Bowerman missed the World Series later that season because his wife Viola was ill. The Giants defeated the Philadelphia Athletics, four games to one. Mathewson threw three shutouts, all of them caught by Roger Bresnahan. Bresnahan was a younger, faster athlete who became the Giants’ primary catcher that year.

During the 1905-1906 winter break, a Pittsburgh paper reported that the Cincinnati Reds, looking to strengthen their catching position, expressed interest in a trade for Bresnahan. The potential deal went nowhere, so the Reds inquired about Bowerman. Ned Hanlon was the Reds’ new skipper for the 1906 season, and he remembered Bowerman from his time in Baltimore. It was reported that Hanlon believed that the veteran was “just the man to put ginger into the Reds backstop department.”32 The Giants and manager McGraw crushed any possible deal by insisting on three players, including pitcher/outfielder Cy Seymour. Seymour ended up being sold to the Giants anyway during the 1906 season.

During the 1907 season, Bresnahan, and then Bowerman, became the first backstops in the majors to don shin guards. A writer commented, “When Frank pranced out arrayed in all the newest inventions to protect the catcher, including Roger Bresnahan’s awkward but spectacular looking shin guards, he looked fit to stop a freight train, to say nothing of a baseball.”33

The pair’s rivalry over catching duties intensified. Bowerman’s unhappiness and resentment towards Bresnahan reached a point where McGraw finally engineered an eight-player trade with the Boston Doves before the 1908 season. The Giants received Tom Needham, who would become Bresnahan’s backup.34 They also got Al Bridwell and Fred Tenney. Besides Bowerman, the Giants sent George Browne, Bill Dahlen, Cecil Ferguson, and Dan McGann to Boston.

Bowerman performed as a player with the Doves in 1908 and as a player/manager in 1909, but the managerial stint did not work out well. He stated that he was unable to get a winning combination out of the players. The ex-catcher also objected to a trade of outfielder Johnny Bates and Charlie Starr to Philadelphia for two pitchers, Buster Brown and Lew Richie.35 A third player, infielder Dave Shean, was also included in the deal. After posting a 22-54 record, Bowerman left the team and was replaced by Doves catcher Harry Smith.

Bowerman’s time in the major leagues had ended. He posted a .250 batting average during his 15 seasons, with a .963 fielding percentage (as a catcher). His .314 slugging percentage included 13 homers.

By then in his 40s, Bowerman continued to play baseball at the minor-league level, finishing the remainder of 1909 with Indianapolis Indians of the American Association. He returned to Indianapolis for the 1910 season. In 1911, his final year as a player, he got into 79 games at first base and posted a .256 batting average for the second-place Kansas City Blues of the American Association. At age 43, he managed the London (Ontario) Tecumsehs of the Canadian League in 1912.

That ended Bowerman’s professional baseball career. He returned to Romeo to resume life as a successful peach farmer. After Viola passed away in 1909, he married her cousin Rose Miller on November 30, 1912.36 The marriage produced six children, including three boys (Byron, Thomas, and Francis Eugene) and three girls (Margaret, Viola, and Mollie Jane).

The return home to Romeo didn’t end Bowerman’s love of playing baseball, however. He played with his sons Byron and Edward on the Romeo Buick baseball club from 1915 to 1925. Byron was also a catcher with Nashville in the Southern Association and Edward was a pitcher at the University of Michigan.37

Bowerman participated in an old-timer’s game at Detroit’s Navin Field in October 1930. The game matched Hall of Fame pitching greats Cy Young and Grover Cleveland Alexander. Bowerman was the catcher for Alexander’s squad and was able to face Young as a hitter. He singled off Young and announced after the game, “Now I am through. I have played my last game of baseball and I’m satisfied.”38 Bowerman recalled that his first major-league hit was also off the legendary hurler. He concluded, “That’s enough for me. I started against Cy Young, and I’ll quit with him.”39 It should be noted, however, that Bowerman’s claim on this subject is not supported by the historical record – he did not mention his two singles the previous season.

In April 1935, Bowerman sent a thank you note to Ford Frick, who then worked in the Baseball Commissioner’s Office as head of the National League Service Bureau. Before becoming National League president sometime later that year, Frick was in charge of public relations and had issued a lifetime pass to Bowerman to all National League games. Bowerman’s letter included comments that he preferred an American League pass because Detroit was only 30 miles from Romeo and any National League city would be way too far away for travel purposes.40

During the summer of 1938, Bowerman supervised a nonprofit baseball fundamentals camp for youngsters on his farm. He believed three principal shortcomings held back youngsters from their baseball potential. The first was imitating star major-leaguers by attempting to play a position not necessarily suited for them. The second was defensive mistakes caused by “fighting” the ball in the field. The third involved lacking rhythm while batting.41

Bowerman was once asked whom he considered to be the game’s greatest catcher. While considering many choices, he replied, “Buck Ewing is the greatest man who ever put on a glove.”42 Of receivers, he once commented, “Hard work will improve a catcher of fair ability, but if he isn’t to the manner born, he will never be a top notcher.” 43

Frank Bowerman passed away on his farm in Romeo on November 30, 1948. He was five days shy of his 80th birthday and had been suffering from stomach cancer and chronic myocarditis.44 He was survived by second wife Rose; four sons, Dr. Edward Bowerman, Byron Bowerman, Thomas B. Bowerman, and Francis B. Bowerman; and three daughters, Mrs. Viola Schoff, Mrs. Margaret Knapp, and Mrs. Mollie Jane Akers.

In a tribute to Bowerman, Detroit sportswriter Bob Murphy concluded his column as follows: “Somewhere the greatest umpire of all is yodeling: ‘Mathewson pitching. Bowerman catching.’”45

Acknowledgments

This biography was reviewed by Bill Lamb and Rory Costello and fact-checked by Mark Sternman.

Sources

Frank Bowerman file maintained at the Giamatti Research Center in Cooperstown, New York.

Baseball-Reference.com and Retrosheet.org.

Ancestry.com

Notes

1 Another moniker, “Pea Juggler,” came from eating peas with a knife, while not spilling any of them. “Pea Juggler May Retire,” The Herald-Press (St. Joseph, Michigan), February 17, 1912: 7.

2 Leo MacDonell “Bowerman’s Hands Were Without Equal,” Detroit Times, December 2, 1948: 48-C.

3 “Warlike Finish to Giant Series,” Cincinnati Enquirer, September 1, 1904: 4.

4 “Clarke Cowardly Attacked,” Pittsburg Post, June 27, 1903: 7.

5 “Frank Bowerman Tells of Row with Fred Clarke,” (Mansfield, Ohio) News Journal, June 29, 1905: 9.

6 “Giants Catcher Run Over,” New York Times, September 6, 1906: 4.

7 Leo MacDonell, “Bowerman Hailed as Gamest of All,” Detroit Times, December 1, 1948: 28-C.

8 MacDonell, “Bowerman Hailed as Gamest of All.”

9 “Frank Bowerman Recovers,” New York Times, August 27, 1907: 5.

10 “Bowerman Has Double,” (Stockton, California) Evening Mail, May 24, 1910: 8.

11 “Called Non-Advertising,” Cincinnati Enquirer, July 8, 1888: 1.

12 “Frank Bowerman, Caught for Giants,” New York Times, December 1, 1948: 29.

13 “Detroit Creams,” Baseball-Reference.com.

14 Ancestry.com.

15 “Saffron Ball,” Boston Globe, October 10, 1897: 4.

16 “Baltimore Wins the Temple Cup,” Pittsburg Daily Press, October 12, 1897: 6.

17 “Fred Clarke’s List,” Evansville (Indiana) Journal, March 2, 1900: 2.

18 “What Will Freedman Do?” (New York) Sun, March 11, 1900: 8.

19 “Changes Will Help Baseball” Pittsburgh Press, March 11, 1900: 14.

20 A New York Times obituary reported that before passing away, Bowerman recollected that he had recruited Mathewson for the Giants, persuading John McGraw to add the Bucknell man to the team roster. But the obituary further stated there was no evidence that Bowerman ever recruited the pitcher and referred to a 1925 New York Times obituary of Mathewson and a 1943 Sporting News article by baseball historian Fred Lieb on Mathewson. Neither column mentioned any such event ever having occurred. Plus, McGraw did not join the Giants until 1902.

21 Bowerman Hall of Fame file.

22 Bob Murphy, “Frank Bowerman, a Legend Passes,” Detroit Times, December 1, 1948: C-27.

23 Frank Bowerman file, National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum, Cooperstown, New York.

24 “Three Giants Who are Hitting the Ball Hard These Days,” (New York) Evening World, May 17, 1902: 4.

25 Bob Murphy, “Frank Bowerman, a Legend Passes,” Detroit Times, December 1, 1948: C-27.

26 “McGann Punches Abbott,” Boston Globe, April 23,1905: 4

27 “McGann Punches Abbott.”

28 “McGann Punches Abbott.”

29 “McGann Punches Abbott.”

30 “McGann Punches Abbott.”

31 “Frank Bowerman, Caught for Giants,” New York Times, December 1, 1948: 29.

32 “Cincinnati is Weak in Catching Department,” Pittsburgh Press, February 2, 1906: 20.

33 Peter Morris, Catcher: How the Man Behind the Plate Became an American Folk Hero, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, (2010): 230-231.

34 Cait Murphy, Crazy ’08, (New York: Harper Collins, 2007): 29.

35 “Frank Bowerman Resigns,” New York Times, July 17, 1909: 5.

36 Bowerman Hall of Fame file.

37 Leo MacDonell, “Bowerman’s Hands Were Without Equal,” Detroit Times, December 2, 1948: 48-C.

38 “Hit off Young Ends Baseball Career,” Detroit Free Press, October 6, 1930: 17.

39 “Hit off Young Ends Baseball Career.”

40 Bowerman Hall of Fame file.

41 Bowerman Hall of Fame file.

42 Bowerman Hall of Fame file.

43 “Good Catchers Are Born,” St. Joseph (Missouri) News-Press, March 28, 1906: 3.

44 Bowerman Hall of Fame file.

45 Bob Murphy, “Frank Bowerman, a Legend Passes,” Detroit Times, December 1, 1948: C-27.

Full Name

Frank Eugene Bowerman

Born

December 5, 1868 at Romeo, MI (USA)

Died

November 30, 1948 at Romeo, MI (USA)

If you can help us improve this player’s biography, contact us.